QUEEN STREET

Liberty, Trinity, Niagara

York's fort;

Toronto's reserve

The Garrison: birthing,

briefly losing, & long shaping

a very British town

|

Tent city mistress

Monument to founder John & wife Elizabeth (her words below) at Simcoe Place, midway between the spot where they first pitched canvas & the turf where their town would rise. |

-

"The Queen's Rangers are encamped opposite to the ship. After dinner we went on shore to fix on a spot whereon to place the canvas houses, and we chose a rising ground, divided by a creek from the camp, which is ordered to be cleared immediately. ...

"We went in a boat two miles to the bottom of the bay and walked thro' a grove of oaks, where the town is intended to be built. A low spit of land, covered with wood, forms the bay and breaks the horizon of the lake, which greatly improves the view, which is indeed very pleasing. The water in the bay is beautifully clear and transparent."

-- Elizabeth Posthuma Simcoe, in her diary, York, Tuesday, July 30th, 1793

In deep downtown Toronto, near the foot of a gleaming glass office tower finished not very long ago, this unfinished city gives belated thanks to one very formidable lady. It is her husband John who gets credit for founding the town, but it is to Elizabeth Simcoe we have turned, ever since, for our sense of this place as they found it more that 200 years ago.

Undaunted at what a later lady, Susanna Moodie, would call "roughing it in the bush," Mrs Simcoe wandered the landscape -- sketching, painting watercolours, and diligently keeping a diary. Her words above appear on a plaque, sheltered by stiff plastic moulded to seem stretched canvas, on turf called Simcoe Place.

The name can seem new, lately applied to the courtyard between that office tower (which shares it) and the big red white & black box of the CBC Broadcast Centre, plunked there in the early 1990s. But Simcoe Place was born on maps of the late 18th century. Nine acres bounded by John, Simcoe, Front, and Wellington, it was from 1829 site of the Legislature of Upper Canada; from 1867 to 1893, of Ontario. Government House, residence of the lieutenant governor, was up at Wellington Street; farther north at King, Upper Canada College.

That corner, also marked by St Andrew's Presbyterian Church and a tavern, was long known in local lore as "Legislation, Education, Salvation -- and Damnation." The latter remain, a later St Andrew's and not a few nicer places to drink, joined in 1982 by Orchestration: Roy Thomson Hall.

But elite educators, provincial legislators, and lieutenant governors have long since fled north. The old legislative building saw brief use as a mental asylum; in 1900 it fell to freight sheds and marshalling yards of the Grand Trunk Railway. Then to dereliction. Now we have John, Elizabeth and (more or less) their tent.

It is not the spot where they first pitched that "canvas house," once the cargo of Captain James Cook. That lies nearly a mile west.

|

Tent-site garrison

Fort York, seen from the air c 1973, hemmed in east (top) by Bathurst, south by the Gardiner Expressway -- which nearly ran it over. Below, route from the Bathurst bridge: white blockhouses built in 1813, the brick East Magazine, 1814. |

|

Tall towers;

Georgian banner Downtown & the CN Tower rising east of Fort York. Foreground right: the Stone Magazine, 1815, bombproof storage for gunpowder -- 900 barrels holding nearly 37 tonnes. Below, one of two flags the Fort flew (& still does): until 1801 without the red Irish cross of St Patrick set in Scot St Andrew's white X; thereafter the modern Union Jack. |

|

Food & fortifications

The 1815 Officers' Brick Barracks & Mess Establishment (the city's oldest surviving residential structure, much later ones behind), seen past one of two less grand brick digs. Below: earth berm walls backed by stone; stone wall at the western gate. |

There, now, we find Fort York. It's not the camp Mrs Simcoe saw in 1793: most of the current Fort dates from late August 1813. Accounts vary as to which side of that dividing creek the Simcoes chose to set up housekeeping. Some say the west, where in 1800 the first Government House would rise (well, the second if we count that canvas one). Carl Benn, the Fort's curator and chief historian, says it was on the east.

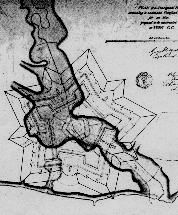

Husband John had both sides fortified, if mostly the west -- and modestly: two barracks, by the next year 28 more and maybe a stockade, all of green logs likely to rot. He did not expect his works to stand for more than seven years.

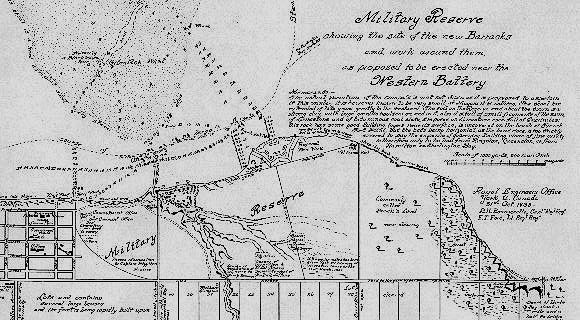

They would fall sooner, torn down in 1797 (Simcoe then gone to another outpost of Empire), replaced on the east by a blockhouse and 19 huts serving as barracks, hospitals, a bake house and a canteen, ordered by his successor Peter Russell. The creek's other side got two new works in 1811: the west wall, still there, and the Government House Battery, facing south, rebuilt in 1813 as the Circular Battery.

Even then it was not, in name, Fort York: people more often called it "the Fort at York," or "the Garrison at York" -- or, mostly, just "the Garrison." The stream between became Garrison Creek.

|

| The Garrison & its creek: Painting by Sempronius Stretton, May 13, 1804: blockhouse & barracks on the stream's east side, Anishnawbe spearfishing from a canoe beneath its steep banks. Native people were ubiquitous "local colour" in paintings of the period, many meant for domestic consumption "back home." |

The Fort York we know began as a repair job, much needed: on August 1, 1813 American forces -- on the second of three visits that year (the first is detailed below; on the third, August 6, their fleet was fired on and sailed away) -- burned Russell's Garrison. Just 25 days later rebuilding began, all on the west side of Garrison Creek, the east abandoned.

The oldest buildings we see today -- Blockhouses Number 1 and 2, white with overhanging second storeys to let soldiers shoot down through the floor onto the heads of onrushing attackers (who in fact never again rushed in) -- date from that 1813 reconstruction.

The East Magazine went up in 1814 as secure storage for gunpowder. Its walls proved too weak to support its vaulted roof, bombproof: in 1824 it was removed, another storey added in its stead. The Stone Magazine, with walls more than two metres thick, was built in 1815.

The Brick Barracks also date from 1815: two were for enlisted men, some with wives and children; each could sleep 100 dependent souls. The Officers' Barracks and "Mess Establishment" held fewer, including servants and, for those of high rank (like a few of York's ranking gentry, the Jarvises and Peter Russell among them), perhaps the occasional slave. Its Mess was, for a mess, quite elegant.

The British Army held the Garrison for 77 years -- but for two brief breaks. Imperial troops were withdrawn from Canada in 1854, sent to fight the Crimean War, staying away two years. The first withdrawal, earlier and less orderly (as we'll see), lasted just 11 days, its war much closer to home.

In 1870 British forces (but for the Royal Navy at Halifax, "Warden of the North" through World War Two, and at Esquimalt, BC) left Canada for good. Troops under Canadian command, many of them British Army veterans, first took Fort York in 1872. They would be there another 60 years, after 1903 as tenants: the City bought the Fort, if letting the army stay on.

But even before that it had become "Old Fort York," by the 1970s "Historic Fort York" -- in short a theme park. Of sorts. Beginning in 1932 the City restored its crumbling structures; on Victoria Day 1934, to mark Toronto's centennial (York and the Fort some 40 years older), it opened as a museum, the Right Honourable Vere Brabazon Ponsonby, 9th Earl of Bessborough, then Governor General of Canada, presiding.

The Fort, if no longer an official fort, saw military use as late as World War Two. The City cleaned it up again afterwards, reopening it to the public in June 1953. Fort York is now a designated National Historic Site, run by Heritage Toronto under the City's Culture Division (rather a military ring, that).

It might have become a true theme park: not a real historic site but its replica. In 1958 the Metropolitan government said they wanted to tear down Fort York: it stood in the path of their planned Gardiner Expressway. They offered to rebuild it "where it belonged," on the lakefront -- since pushed by fill nearly a third of a mile south -- to "create a sense of the fort's original geographic context."

Actual history was to fall for a "sense" of history; authentic barracks, blockhouses, and blooded ground to the pathetic ersatz -- '50s style. Metro, the provincial Tories, and the local media (ever boosters of "civic progress") pushed the plan; the Toronto Civic Historical Committee, with allies across Ontario, pushed back.

The Battle of Fort York, 1958, was won by history, not "heritage." The Toronto Star, its editorial finger ever in the wind, switched sides -- shamelessly running a map of the Gardiner's new route in 1959 with an arrow aimed at the 18th century site tucked beside: "Old Fort York will not be touched." The Garrison, though under the roar of a monster on stilts, did not (this time) surrender.

Toronto's Garrison is now held by the Fort York Guard. They are not real soldiers -- but they do not seem fake ones. Their uniforms, if of modern manufacture, are scrupulously true to history: their buttons (each regiment had its own, distinct) have been specially cast; the odd bit of lace (each, too, using threads of distinct colours) carefully ordered up. And they know how to muzzle load a musket without blowing off their heads. Or yours.

|

Soldier boys (not toys)

Fort York treats tourists to fine uniforms & real musket fire, some of its "soldiers" (like the sentry at ease atop this page) mere boys -- as were many of the Fort's real ones. But they are more than tourist toys: their guns, powder, shot & uniforms are true to history -- many well versed in that history. Producers of the CBC's Canada: A People's History had high praise for military "re-enacters," insistent on faith to the finest details.

I got a guide not in British uniform, done up like the local militia -- his tunic so modest he might have slept in it (as they likely did). I was, by chance, his sole tourist, so got to ask lots of questions. He knew his stuff. |

The Guard, formed in 1955, has as its core university graduates in history; most part time Guards are history students. And all of them teach history -- on the very spot where it was made: all summer, from Victoria Day, school tours are the Fort's primary (even secondary) focus. Women also offer history there -- if dressed for roles historically filled by women in the early 19th century.

We get to see not just boys with guns but girls in kitchens, messing up for real from ancient cookbooks (and yes: you can eat it; for the finer dishes you can book a dinner in the Officers' Mess Establishment). We see women in barrack rooms where women, their husbands, and children shared big wooden bunks -- in 1815, as many as 32 people in one room. A single regiment once had 15 wives and 60 children attached. (And yes: kids today can sleep over.)

The Summer Student Guard gets to show off musket play (carefully trained, often by military re-enacters who know the hardware) and stern regimental display. Here it helps that they are not real soldiers: the British Army's 18th century drill was not quite that of the Canadian Armed Forces in the 21st.

It can be -- even for me, having seen my last fort as a high school kid: one much too real, American, and maybe my future if I hadn't escaped -- quite impressive. And great fun.

But we gambol -- if a bit earnestly, murmuring between musket displays -- where arms were once borne in dead earnest. The ground beneath our feet has been (as Americans are more inclined to say than we) sanctified by blood.

The War of 1812, when the United States invaded Canada, is the war Americans mostly forget. Topped in domestic divisiveness only by the one in Vietnam (the only one America ever lost, they say), this second battle with Britain ended, at best, in a draw. Canadians count it a victory, if for no more than the fact that Canada is -- as Americans then hoped it would not be -- still here.

Declared by Congress on June 18, 1812 -- angered at the Royal Navy's fondness for Americans on the Atlantic, "pressed" into service on Limey frigates to save King George from Napoleon -- this war for freedom of the seas would be fought solely, but for the Great Lakes, on land.

The US had nearly no navy: Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry's famed cry -- "I have not yet begun to fight!" -- had yet to be uttered. They could hardly attack the British Isles. But British North America was just next door, often allied with First Nations still free, standing in the path of Manifest Destiny. The American West, and South, were 1812's Hawk hotbeds.

New England was Dovish, closely tied to Old England by trade (unhalted even by federal law: the "Non- Intercourse Act"), often subverting "Mr Madison's war," even threatening to secede from the Union. Canada would see divided loyalties as well: of the 75,000 people in its (then) western half, Upper Canada, most had just lately arrived. From the United States: their one true allegiance was to free land.

General Isaac Hull urged (from Detroit, which in August 1812 he would surrender without a fight to Major General Sir Isaac Brock, backed by very scary Mohawks): "Raise not your hands against your brethren.... You will be emancipated from tyranny and oppression and restored to the dignified position of freemen."

To not a few Upper Canadians, his appeal would have no little appeal. Many sat out the war; some came to the aid of their "brethren."