QUEEN STREET

Jarvis Street east to the Don River

Blight & the

Brave New World

Rural estates to urban renewal:

Moss Park, Trefann Court,

& Corktown

|

Allan estate, & bequest

Moss Park, overlooking The Meadow in 1842. Below: the 1910 Palm House in Allan Gardens, third horticultural pavilion on the site. |

|

Anchoring the antiques trade

The former Waddington's auction house, at 189. Other auctioneers & decorators still thrive -- if not all. |

Healing circles

More than 16,000 indigenous people live in the Toronto area, if not gathered in native nabes (but for the whole city -- not clearly ceded by treaty until 1923).

Their community's focal point is the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto at 16 Spadina Rd, with programs in Cree, Mohawk, Ojibway (they teach Ojibway) & Mi'gmaq -- language of Atlantic Coast peoples who, like many from down east, end up in Toronto. They also host a women's circle & a food bank.

Here, Anishnawbe Health Toronto at 225 Queen East emphasizes holistic health (chiropractors, naturopaths, traditional elders & healers), & HIV. Two-Spirited People of the First Nations, a same-sex (if not conventionally "gay") group, also does AIDS work in the community.

Up Parliament at 438 Dundas the Council Fire Native Cultural Centre has a drop-in, free meals, family & pre-natal services, the Life Long Care Program for seniors, & 7th Fire, a youth drum group promoting "Native spirit & freedom from drugs & alcohol."

Council Fire also speaks Oneida. First Nations were "multicultural" long before the term was coined.

|

|

East of Sherboune

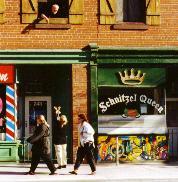

Queen of schnitzel (with a key toss?); below, He & She's fetish queens. |

Coming to the corner of Queen and Jarvis, we stand midway along the foot of Park Lot 6, granted to William Jarvis, Civil Secretary of Upper Canada, by Governor (and fellow Queen's Ranger) John Simcoe in 1793.

Jarvis had many descendants. Years ago I chanced on one, or so he claimed and credibly: he was tending family plots in St James' Cemetery. A namesake son, as Sheriff Jarvis, led forces facing the Rebels of 1837 in a skirmish quite Canadian -- famed as "the first spontaneous mutual retreat in the history of warfare." The site, near modern Maple Leaf Gardens, remains unmarked.

Secretary Jarvis didn't live on his estate, setting up with the gentry on Front Street. Son Samuel Peters Jarvis did, in 1824 building a manor there named Hazelburn, after a "burn," or creek, just east. He later sold off land for development, running Jarvis Street up the middle toward Rosedale, the Jarvises' own speculative suburb -- if one failing to bloom before the early 20th century.

Hazelburn soon got company across that creek, in Park Lot 5: William Allan, with the Bank of Upper Canada, bought it in 1819. "Mr. Allan's new house," Mrs Jarvis complained, "puts us completely in the background being three times the size."

The city's first Greek Revival palace, Moss Park looked south over The Meadow, a damp field then marking the east end of Lot Street (it would later head beyond, as Queen). The house had grand halls, a library, and many bedrooms: the Allans would have 11 children. Only one, George William, survived his father. In 1857 he granted the City land to the north, where future citizens might "share with him his lifelong love of flowers." In 1901 it was named Allan Gardens.

Moss Park survived to 1904, Allans in it nearly as long. The City bought the land (saving it from a baking plant) and tore down the house for a park, not built for years. It survives now only in name: Moss Park Armoury (in fact on Jarvis land); Moss Park Arena, south of the John Innes Community Centre facing Sherbourne; beyond, the Moss Park Apartments -- far from the grandeur of their namesake.

But this area east of downtown had no one name, no coherent identity; it's sometimes called simply East of Downtown. The City has dubbed nabes north to Allan Gardens "The Garden District" -- rather a stretch on this stretch.

It boasts no auspicious entry: at Jarvis Queen's north face falls away, armoury and arena set back from the line of 19th century streetscape once here. Between them is grass, offering a view to Victorian survivors way up on Shuter Street. South across Queen there are 19th century remains, many storefronts peddling antiques. The area has long met more mundane decorating desires: Ontario Paint & Wallpaper has been at 275 Queen since 1913. But many since have come and gone -- even as promoters tried to dub this the Lower East Side. Talk about a stretch.

In his 1990 tour Edward Relph noted here "major changes in urban character taking place as buildings are converted to new uses" -- a classic example of what urban geographers call a "Zone of Transition."

|

|

|

|

|

Modern Moss Park

The Armoury:1964 successor to the gargantuan pile on University Ave. The Arena: past grass to the east, facing Sherbourne. Shelters: Fred Victor at Queen & Jarvis, the Sally Ann's Maxwell Meighen Centre across from the arena at 135 Sherbourne. |

Transition to what, exactly, remains to be seen. Also remaining is evidence of what it once was, and to some extent still is. In his 1968 novel Cabbagetown, a coming of age story set during the Depression, Hugh Garner has his main character wander west from his own neighbourhood (the original Cabbagetown, now Regent Park) into this one.

- "He crossed Sherbourne Street into the heart of the city's criminal, drug, and prostitution district, a neighbourhood that not only led the country in most crimes, but also in its incidence of tuberculosis, venereal disease, illegitimacy, incest and percentage of social welfare recipients. It was a neighbourhood of common-law unions, hamburgers, the deserted and deserting spouse, the lonely drinker and the lonelier sleeper."

At the southeast corner of Jarvis and Queen is the Fred Victor Centre, better known as the Mission: begun by one Mrs Sheffield as a home for young men out of work, taken on by Methodists in 1866, from 1894 housed in a grand building donated by the Masseys; son Fred Victor had died young. Here at his namesake mission, in digs decent if less grand, the United Church of Canada shelters men young and old, many homeless.

The street's open stretch on the north also sees the homeless, many at the corner of Sherbourne; the Salvation Army's Maxwell Meighen Centre, another men's shelter, is just up the street. On its south corners are the old Canada House Tavern and a block '50s Bank Branch Modern, the style TD. But Toronto Dominon has long gone to donuts: Coffee Time, open 24 hours a day.

Queen and Sherbourne can sometimes feel grim, the sort of corner casting much of Queen East, to some eyes, as a "No Go Zone." But it has its comforts, even some grandeur. Here a stretch of 19th century streetscape survives, housing shops tawdry and trendy, tenants in walk-up apartments behind Victorian façades rich in brickwork and woodwork often bright with paint.

Friends of the early '70s lived over Mary's Coin Laundry at 224, later passing that big rambling flat to other friends. Mary's is still there. So is washing of another sort: a terra cotta Lamb of God beneath their third floor window. The 243 Barber Salon across the street survives from that time, as do Schnitzel Queen, Diamond Taxi dispatching cabs from Queen for decades and, next door, Downtown Collision.

|

|

|

In the '80s, working on The Body Politic's office, I got material from one of the paper's most loyal advertisers: Queen Lumber at 331, its yard beside still open to the street. The Berkeley Street Wesleyan Methodist Church of 1871 just beyond has gone secular, promoted as a party venue by a model of it in James Gault's window (on offer there: "Resources for Eclectic Lifestyles"). Less modest models perch outside 263: He & She, for lifestyles livened by "Fetish & Fantasy."

|

|

|

All this sits just north of Toronto's birthplace: the ten small blocks between George (just east of Jarvis) over to Berkeley, from Front Street up to Adelaide. Signs there with bright yellow tops, put up by the City circa 1973, mark another time and place: 1793, and the Town of York.

The streets there now were there then -- if some with other names: Berkeley was first called Parliament; Adelaide was Duke. Sherbourne, leading down past Richmond (once Duchess) to the heart of Old York, began its life as Caroline.

|

Streets of 1793

Simcoe named his town for the Duke of York, streets for him too (Duke & Frederick), & for related royals. George III got King, the Prince of Wales (later George IV) George. The remaining royal boys got Princes' St -- later called Princess. (The Canadian National Exhibition's Princes' Gates also get Princessed, if named in 1927 for David & Bertie, later Edward VIII & George VI.)

Caroline of Brunswick, Princess of Wales, got one -- if, after scandal, losing it to the owners of Park Lot 4: the Rideouts; their estates, Britannic & local, were called Sherbourne.

Further east on Queen (above), other signs mark 1793: King's Park, initially set aside as a timber reserve for the Royal Navy.

The area is now going to condos, Kings Court (left) set to overwhelm a bank once lording over King & Sherbourne. |

|

Dreams of "renewal"

Towers of Moss Park set back from Queen; tenants claim the yard -- with a yard sale. Below: Berkeley St, passing an old building put to new use, crossing Queen -- to dead end in Moss Park. |

|

Government's house & housing the governed

Parliament Street, route of "renewal" -- Regent Park, Cabbagetown (old & "Old"), & St James Town. |

|

Master builders meet citizen activists

Trefann Court: The beginning of the end of "urban renewal." |

|

Concrete loss

St Paul's Power Street, guardian of Corktown, a community run over by cars. |

|

Victorian bombast

Office block of the 1870s Dominion Brewery (& 1970s Dream Factory); right, its wings spread along Queen. |

Across Queen from Queen Lumber, streetscape retreats again: just past a sports bar (Who's on First?) and Mimi Variety, Seaton Street heads north -- and stops. Beyond, far back, sit towers: the Moss Park Apartments.

Well before 1990, when this area was called a Transition Zone, it had seen dramatic transformations -- in the name of progress and "urban renewal." The term would turn out egregious euphemism; some, more aptly, would call it "urbicide." The names I've applied to this mostly unnamed area mark three communities flanking Queen, all once subject to the whims of modern planning.

On a side tour up Parliament Street we'll see more. Here we'll see the ideas behind them. Bold ideas, radical in their day, promoted by heroic visionaries undaunted at vast efforts to eradicate urban decay. As planner Stanley Pickett put it in 1957:

- "It is no light task to undertake the demolition of people's homes and places of business, to replan large areas, ...one of the most difficult operations which has ever been successfully carried out in the field of human living and environment, ranking with the tremendous problems posed by war, by famine, and by refugees.... Nevertheless, our cities must be renewed; for if they are not, the blight spreading at the centre will slowly and insidiously strangle the efficiency of the city and may eventually render it unable to carry out its functions...."

Moss Park: Winged towers; no streets.

Modernist visions: Suburban vistas clear scary streetscapes; '50s "Redevelopment Project" for Regent Park South (not what got built).

Model city (here literally): Le Corbusier's 1925 Voisin Plan for Paris; "mess & complexity" cleared for linear efficiency. |

Blight & the Brave New World

Urban planners who gave us the likes of Moss Park were ever on about "blight," speaking of it as a disease, old buildings its worst symptom.

Toronto's Eugene Faludi wrote in 1947 that their "haphazard" replacement might retard "the progress of blight" -- "but the sources of the disease will remain to infect these areas. ... Rehabilitation can be accomplished only by the wholesale attack on the problem involving replanning and rebuilding on a large scale."

This experiment in social hygiene was often resisted by stodgy bureaucrats and, as Faludi said, "the 'common man' for whom a brave new world was supposed to be built" -- if backed by "people who always support progress and advanced thoughts."

Among them planners inspired by Ebenezer Howard's Garden City of 1898 or Frank Lloyd Wright's Broadacre, "uniting desirable features of the city with the freedom of the ground in natural happy union" -- planned for suburbs uninfected by the old.

Or by Le Corbusier's 1925 Voisin Plan for Paris: the ancient city razed, in its place "la ville radieuse" -- tall towers standing free on green lawns with no streets, traffic whizzing by on perimeter highways. Le Corbusier wrote (historian Vincent Scully noted) "a diatribe against the street; he hated its complex multiplicity and what seemed to him its mess and confinement."

Their solution, as John Sewell put it in The Shape of the City: "clear away the old, close streets, and build residential structures with no clear relationship to city streets. It was a formula that urban renewal planners, persuaded by the idea of urban decay, would use many times over."

A formula of perfect rationality, mechanical efficiency: the city as car conveyor and human warehouse -- not a complex living organism; the "new" planted all at once -- not growing, as Jane Jacobs would show it truly does, out of the old. "Blighted" buildings often shelter dreams too young to afford upscale rents; "urban decay" can be fertile ground.

Ground gone to reason's grand plans can often become a desert. |

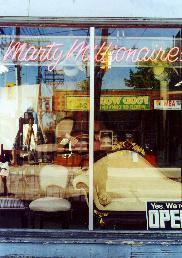

Wandering east on the south side we pass the Robert Deveau Galleries at 299 (auctioneers, there for ages and rather grand); Neighbourhood Legal Services, there since 1973; Pollack Sporting Goods; then furniture: Marty Millionaire. We are at Parliament Street.

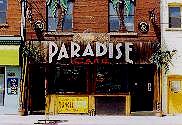

Nothing looks parliamentary. Government House, once down the way, is long gone. The next corner is lined with used cars, Queen Auto Brokers; northeast Mr Tasty promises "Charbroiled food to perfection." Just beyond a café called Only in Paradise seems more promising, if perhaps at a price. Further along is The Gourmet Bun ("the best buns in town") right beside Pete's Open Kitchen, "always delicious foods" -- or at least, so it looks, since the '50s.

|

|

A Hasty Market we passed back at Parliament looked familiar in franchise yellow -- if advertising oxtail, curried goat, and falafels. A tour of that street (linked to below) helps tell why, and how the street got its name.

Just past Parliament on the north side is a street whose name evokes less official history: Trefann. It's modest, even easy to miss, but in a way that's the point. It was here in the late 1960s that modern planners met their match: a "blighted" community that would not be moved. As John Sewell has said (and he was there): "Trefann Court spelled the end of urban renewal in Canada." You can find its story here.

Trefann sits in the shadow of grandeur not civic but holy: St Paul's Power Street -- looking frankly out of place. In a city of Gothic churches we suddenly find the Italian Renaissance (if of 1887), its interior rich with trompe l'oiel -- pride of a community long poor: Corktown, Toronto's first Irish immigrant ghetto, later home to Macedonians.

Past St Paul's long bulk flanking Queen, and behind a chain link fence, is the asphalt playground of the St Paul Catholic school. Beneath it lies more history than, at a glance, one might imagine. Beyond, streets heading south stop short -- blocked by a grassy embankment topped with whizzing traffic. Once intact all the way down past King Street, this community is now carved by concrete: Richmond and Adelaide rising as ramps to the Don Valley Parkway.

Along this stretch many buildings are modest: fewer stores, more houses, many quite old. A row on the south side carries its name and date: Davies Terrace, 1877. A glance up shows this was classic "workers' housing" of the day: a continuous roof unbroken by firewalls. Not that that's kept tenants (some commercial if, as in similar rows elsewhere, some still residential) from considerable investment in the few feet between their wood frame walls.

Two rows on the north side, still modest, look more 1970s -- and are. There's a story behind them, and behind the Edna Dixon Apartments just beyond. Literally behind: this is the Queen Street face of revitalized (not "renewed") Trefann Court.

|

|

|

Workers' housing, 1870s & 1970s:

Davies Terrace (& modern friend) above;

below, a later duplex & much later row.

|

|

But it's not all modesty. Stretching along Queen across from Davies Terrace is the Dominion Brewery, built by Robert Davies in 1878, brewing suds until 1936. Its massive wings speak of industry; its office block of entrepreneurial bombast, even Victorian fantasy.

It was once frankly fantastic, in the late 1970s home to The Dream Factory, a bit of the Queen West scene on Queen East. It's now more sober, if with a hint of funk. Renovations begun in 1987 made it Dominion Square, filled with offices, a high tech photo supply house called Vistek, and Librairie Champlain, a big French bookstore.

|

|

A former knitting mill at 426 Queen, just west, was converted to condo lofts in 1998, 600 square feet going for $140,000. Later industrial blocks further east are now linked, a grand atrium between, as The Queen East Centre -- "The Place for Creative Business" its banners say. Among its tenants are a recording company and the studios of Classical 96.3 FM.

Across River Street we come on newer red brick: headquarters of the Toronto Humane Society. Tucked under its low carport entry just north is a fragment of its history: cow, sheep, horse, chicken, cat and dog (if mainly seeing the last two now, and the occasional raccoon); a bas relief I remember over the door of its much older home on Wellesley just west of Yonge.

Below it is a 1999 plaque marking a bequest by pianist Glenn Gould, his "generous legacy left to thousands of abused, lonely and abandoned animals which continues to provide them with a second chance." The Humane Society has got in trouble for too fervently advocating animal rights, threatened by those who see them in league with activists apt to attack McDonald's. It did lose City funding for its animal rescue service; the Society kept it running, on their own.

One can imagine a day when current treatment of sentient non-human beings will be seen as criminal. For now, the last chance of many is marked just up the way by grim metal stacks: the Society's crematorium chimneys.

|

King's end

If getting here before Queen. |

Flanking the Humane Society beyond River Street, Queen rises up -- though a glance south shows the land slopes down, to the valley of that river: the Don. The rise is man-made, a ramp to the Queen Street bridge. Westbound streetcars pause here, checking a switch that will send them straight along Queen, or on a jog south as the King car.

King Street, beginning far west with Queen at Roncesvalles, running parallel to Queen for most of its route, here ends. If here before Queen: York's main street left town on an angle at Berkeley, crossed Fifth Creek (since buried if then wrapping the town north and east, blocking other streets) and headed toward the river -- as the road to Kingston.

The Don has been bridged here, or near here, since the early 19th century. And often. The fate of one bridge we know for sure: it was burned during the Rebellion of 1837. The current one, and its steel frame approach ramps, went up in 1911.

Queen Street got here not long after King -- if not as Queen until 1844. Beyond the Don it was still Kingston Road, its environs for years still rural. No more. We'll cross the Don for upcoming Queen Street tours -- after the side tours here, if you decide to linger.

And after some time on the river.

See more on:

The Park Lots, in A Line on a map.

Sources (& images) for this page: Vincent Scully: American Architecture and Urbanism, Praeger, 1969 (Voisin Plan, 1925). Eric Wilfrid Hounsom: Toronto in 1810, Ryerson Press, 1970. William Dendy: Lost Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 2nd edition, 1993 (Moss Park, 1842). Edward Relph: The Toronto Guide: The City; Metro; The Region, prepared for the Annual Conference of the Assoication of American Geographers, Toronto, April 1990 (with thanks to Max Allen). Mariana Valverde: The Age of Light, Water & Soap: Moral Reform in English Canada, 1885 - 1925, McClelland & Stewart, 1991. John Sewell: The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning, University of Toronto Press, 1993 (Moss Park plan; Regent Park South Redevelopment Project cover). Camrost-Felcorp Developments (Kings Court condo). Thanks to Bill Eadie for many local details, offered in corespondence, Feb 2002.

Go on to:

Government's house & housing the governed

Parliament Street: Regent Park, Cabbagetown, & St James Town

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/mtc/2pmtc.htm

November 2001 / Last corrected: May 4, 2007

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com