|

BODIES

|

One Street; Many Stories: Queen

|

| | |

|

QUEEN STREET

Liberty, Trinity, Niagara

Not at liberty

Jails (& gaols), Central Prison,

the Mercer Reformatory,

& the Asylum

|

| | |

York's lock-ups

The first gaol, c 1800; the second below, built in 1824.

|

Toronto's eye-cons

Third jail, 1840; below, the Don Jail, open by 1865 (its back at the top of this page). Both look built "panoptical" -- but I can't attest to their interior sightlines.

|

|

The punishment of wayward subjects was an early priority for the rulers of York. It was not a violent frontier town: as in nearly all white settlements across Canada, the forces of order were the first to arrive. But injury to persons was of less concern than crimes against property. And social propriety. The town saw its first execution before its first jail: tailor John Sullivan hanged in 1798 for cashing a forged money order. Its value: three shillings ninepence.

York had spread west just the year before, reserving marshy land south of King beyond New Street (now Jarvis) for market, church, school, hospital, gaol, pillory, and stocks. The last went up first, the hospital never (at least there), the gaol by 1800: a clapboard covered log box behind a stockade of cedar posts 14 feet high, their tops hacked to sharp points.

It stood where Sullivan was hanged, long site of pillory, stocks, and a whipping post. By 1803 the town market sat just east, good burghers bearing glad witness to the enforcement of civil order. On two market days in 1804, two hours each day, they got to scorn a woman pilloried (on top of a six month sentence) for being a "nuisance," a man for "seditious language." Hot iron branding of the hand or tongue, on the program until 1810, was reserved for courtroom spectators.

Subjects locked up lived on bread and water. They slept on straw, dirt below; raised pallets were provided only in 1813. By then the damp ground was rotting that first gaol's wood. A new one rose, in brick, north on King in 1824. It housed petty thieves, prostitutes, people charged with "keeping a disorderly house," the incorrigible in leg irons. Among them were those merely broke: imprisonment for debt went on until 1859. The gaol's cellars held York's feared "lunatics."

It also saw public executions. Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews, convicted of treason after the Rebellion of 1837, were hanged in its yard. Dumped in paupers' graves, they now lie in Toronto's Necropolis, a monument marking their history.

York's gaols were not unusual in form, looking much like other public structures of the day. The second had a twin next door: the courthouse of 1824. They were built for confinement, not -- as later jails would be -- for correction.

The third jail, if the new City of Toronto's first, rose in stone to a design by John Howard, south of Front Street near Parliament (hard by the first, if lost, legislature) in 1840. Work on the fourth began in 1859 on Gerrard, far east, overlooking its namesake river. The Don Jail opened in 1865, William Thomas's grim portal meant to strike fear in the hearts of the wayward (even if they were likely led in by a more mundane side entry).

These jails (the first, on some maps, still spelled "gaol") looked like prisons -- as new prisons had come to look by then. Britain's were built for "moral correction," requiring careful and continuous observation of inmates. As Michel Foucault wrote in Discipline and Punish:

- "The perfect disciplinary apparatus would make it possible for a single gaze to see everything constantly. A central point would be the source of light illuminating everything and a locus of convergence for everything that must be known, a perfect eye that nothing would escape...."

Foucault traced this all-seeing eye back to the French army, and Napoleon's drive "to embrace the whole of this vast machine without the slightest detail escaping his attention." And without ongoing awareness by those under scrutiny that they were, always and everywhere, being watched. At the École militaire pupils lived in small windowed cells, visible to the pupils of vigilant officers. Even in the privy they could be seen -- if not by each other: stalls were framed by full partitions; doors left heads and legs exposed to official purview.

The perfect civil apparatus had been invented by famed utilitarian Jeremy Bentham. His "panopticon" had a central observation tower with direct lines of sight deep into wings rayed around it. By the 1830s Britain had made it the official model for new prisons. British North America looks to have stayed in step.

It was a progressive model -- of utility, efficiency, even liberal humanity; a model born of middle class values then in ascent to official power. Moral "correction" would replace mere, if often brutal, confinement. But, like so many liberal good works, it would try to control wayward bodies not by overt physical violence, but by invasion of reluctant, and often resistant, human psyches.

|

Panopticon 2001

Maplehurst Correctional Complex, model "super jail" set to rise in Milton. Toronto may get one too.

|

|

The Don Jail still stands, its oldest parts now vacant. It saw executions to 1962, another pair hanged then, if getting no monument. They might have: their executions were Toronto's last. And Canada's: capital punishment was abolished by Parliament in 1976.

The panoptical prison is still with us. Ontario plans "super jails" with surveillance clearly in mind: a single "module officer" will do, with the aid of video, what is now the work of ten. The province's modern Tories, punishment still their priority, have spent half a billion dollars on prisons since 1995 -- hoping to contract them out to private operators, looking for the lowest bid (profit margin included).

Toronto may see a super jail: its three current detention centres, the Don included, hold 1,726 inmates, 400 more than intended. By their architects, anyway.

And the panopticon now casts its gaze well beyond prison walls. We live "free" under observation more intense than any inmate of a Benthamite gaol had to know. But we mostly don't know. The all-seeing eye of video surveillance is, to quote Foucault, "absolutely indiscreet, since it is everywhere and always alert ... and absolutely 'discreet,' for it functions permanently and largely in silence."

He wrote that in 1977. Look at us, looking at us, now.

|

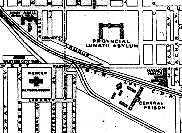

Industry & institutions

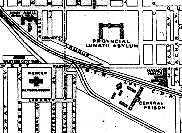

The area southeast of Queen & Dufferin to Strachan Ave, here in 1902. Its biggest buildings, top to bottom & left to right: the John Abell Machine Works; the Provincial Lunatic Asylum; Mercer Reformatory; Central Prison; & the Massey Harris farm equipment factory.

|

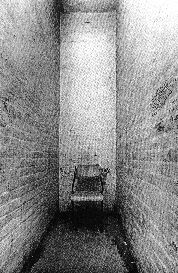

Penal remains

Central's sole survivor, set amidst derelict remains of the John Inglis Company.

|

|

Liberty, the area south of Queen east of Parkdale, was long home to industry, served by the main downtown lines of the Canadian Pacific and Grand Trunk (now Canadian National) Railways. From 1858 it was the site of Toronto's Industrial Exhibition, later moved south as the Canadian National Exhibition. It was also home to institutions; even to industrial institutionalization.

Central Prison, set back from Strachan (often called the Strachan Avenue Prison), was built by the province in the early 1880s -- not only to incarcerate inmates but to put them to work, apparently in the hope of penal profits from their labour.

The work house:

Central Prison, here in 1884. A fragment, left, still stands.

In Toronto: No Mean City Eric Arthur listed the Central Prison (among much else) as "demolished." So I was surprised to find a piece still standing. Which piece is hard to say: its details do not match any in archival photos; they might have been altered over time. Its placement suggests it may be what's left of the south wing.

Workers at the John Inglis Company, there by 1881, could look over the prison fence and see inmates making brooms. They themselves made boilers, later and more famously, washing machines. No one makes anything there now.

Central's industrial dream failed, the prison's life not long: it was closed by 1911. Inglis long stored company records in the block still there, but by 1989 Inglis itself was closed. Its abandoned plant stands with that abandoned chunk of prison, on land otherwise vacant but for brown grass bending in the breeze.

General histories say little of the Central Prison, even less about the Andrew Mercer Ontario Reformatory for Females. Digging in archives and libraries I never found a picture of Mercer, though its building stood until the 1970s. Its site, south of King east of Fraser Avenue, is now the home of Lamport Stadium; the reformatory lives on, if out of town: in 1969 it became the Vanier Correctional Institute -- for boys.

There's more on Andrew Mercer, if little known ("his affluence unspectacularly based on mortgages and land holdings") but for dying in 1871 without a will. The contest for his estate -- among the contestants his maid Bridget and her son (son too of Andrew, she claimed) -- gets a whole chapter in Frederick Armstrong's history. In 1878 Bridget and Andrew "Jr" got a few thousand bucks. The rest of Mercer's substantial estate was forfeited to the Crown.

The province reserved it to fund, as Armstrong put it: "several institutions which were designated with customary Victorian frankness: a training school for idiots; a hospital for inebriates; an industry reformatory for females; and an eye and ear infirmary." So rose the Mercer Infirmary at Toronto General Hospital and by 1880 the Mercer Reformatory -- nothing of Mercer but his name bearing the slightest relation to either. Sex, money, and scandal -- particularly among the gentry -- are always hotter history than hospitals or jails.

|

Fallen women

Bad girls redeemed -- in training as dometic servants at the Mercer Reformatory, 1903.

|

|

Scandalous women and sex for money would be very much part of that other Mercer's history. The Reformatory's "red brick Gothic fortress, forbidding and grubby," as Armstrong recalled it, would see many prostitutes -- and many more "good time girls" there for no more than being "sexually precocious."

As Carolyn Strange wrote in Toronto's Girl Problem: "Working girls who could not give a good account of themselves if apprehended on city streets had always been vulnerable to arrest on the catchall charge of vagrancy." By 1908 the police could widen their catch, using the new Juvenile Delinquents Act -- "delinquent" left conveniently undefined.

In the 1920s, more than a third of Mercer's girls were being held on charges of "vagrancy," one quarter for prostitution. Many others were in for "delinquency," "incorrigibility," "drunk and disorderly." Those convicted of crimes beyond moral offence, like theft, made up just 15% of the Reformatory's inmates.

And they were, mostly, girls. Just 17% were over 30, nearly 43% not yet 20 years old. Until 1893 Mercer housed a Refuge for Girls, some as young as five doing time for petty crimes. It was replaced by the Alexandra Industrial School for Girls, meant for those up to age 16, though some stayed into their 20s. There was also, far north of town, the Concord Industrial Farm for Women.

And there was industry at Mercer, of a sort fit for good girls of the working class. "Fallen women" were to be saved by training for a future in domestic service. Even as the better classes could see a bright future of domestic appliances that would let nice ladies fire their sullen and troublesome servants.

Should girls not be good enough, too "mad for 'the show'" and downtown dance halls, they might be deemed "uncontrollable," "irredeemable" -- simply mad. They had a different future on view. The madhouse was just a block away.

|

Bedlam

St Mary of Bethlehem Hospital, London: "The Madhouse" of William Hogarth's A Rake's Progress, c 1735.

|

|

What our culture chooses to call "mental illness" has, over time, been perceived in guises quite varied. The Ancients attributed emotional extremes to imbalance of vital "humours." Too much black bile led to melancholia. Or to vital organs: a "wandering womb" was the cause of hysteria -- a diagnosis applied to women even in the 20th century. Perhaps even the 21st.

Wandering a desert half naked and ranting -- surely a head case to modern eyes -- John the Baptist was to his time a prophet, later a saint. Muslim societies believed people we'd deem insane were divinely inspired: majnoon (veiled) or majthoob -- pulled, by the grace of Allah. They were given comfortable accommodation in the mauristans of early Islamic cities, some luxurious -- if sometimes resorting to physical restraint in cases of divine excess.

In the late Middle Ages, Jacalyn Duffin writes, "social control of deviance became a major preoccupation." Odd behaviours were blamed on demonic possession; their "treatment" included beating, whipping, execution, or rounding up by sailors for exile -- from which we get "ship of fools."

"Witches" would suffer the dunking chair, stoning, or frying at stakes piled with faggots aflame. Religion, repression, and madness often kept company: priests and nuns, not just brides of Satan, were commonly afflicted.

Mostly the mad were warehoused, out of sight. St Mary of Bethlehem was a hospital; it became not a medical facility but a custodial madhouse: London's notorious "Bedlam" -- where the better classes found it chic to go for a goggle.

It was only in the 18th century that "asylum" reclaimed its oldest meaning: a place of refuge, care, and restoration. The Engish Quaker William Tuke, Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia, and Phillipe Pinel at his Bicêtre for men and Salpêtrière for women in Paris, believed that the mad were in fact "sick from emotional or 'moral' causes, and that their treatment should be based on emotional or 'moral' principles."

A later painting nobly depicts Pinel Delivering the Insane, their chains cast away. But this liberation would turn out more figurative than literal. Pinel delivered bodies unchained to the ministers of moral reform. Their fetters, less obvious, would be more insidious: many would do their utmost to chain the soul. Their temples of moral treatment would swell vast.

|

|

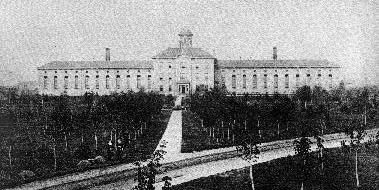

999 Queen Street West:

Stretching behind its wall above, with mid-century passers by on the street outside. Left: its face & dome pondered in a photograph taken in 1868.

-

"O! Visitor to Toronto 'La Belle' standing by the City Hall,

Walk due west 'long Queen street, 'till you come to a high stone wall;

Within the walls is a palace, extending right and left,

This dear visitor is the home, for people of sense bereft,

There are illusions and delusions, around you by the score,

But on this point, I'll not say much, being sensitive and sore...."

-- Graeme L, a patient at the Toronto Hospital for the Insane, 1907

Joseph Workman had come to Canada in 1829, an Irish immigrant who got his MD at McGill in Montreal, later teaching midwifery at a medical school in Toronto. He was a man of progressive vision: he firmly believed the mentally ill were in need of "moral therapy."

In Toronto they'd been locked up in common jails, for a time in the disused second legislative buildings at Front and Simcoe streets. (The abandoned King's College block at Queen's Park would later house "female lunatics.") In 1853 Workman was named superintendent of a new Provincial Lunatic Asylum, set far from downtown in green fields east of Parkdale.

Begun in 1846, it was the third biggest asylum in North America, Toronto not yet home to 20,000 souls. Its four storeys stretched 584 feet along Queen Street behind an even longer wall, massive and 16 feet high. Its tin dome could be seen for miles. It was "an enormous building for its time," by far the biggest in the city.

Its architect was also a man of vision: John Howard. He is best remembered as a benefactor: his estate, donated to the city, became High Park. And he intended beneficence here. His 1840 jail had tiny windows; here were big ones (if still with bars). There were corridors 14 feet wide, leading down each long wing to open verandas. There was hot and cold running water, rare at the time, fed by a 12,000 gallon tank nestled inside the dome. There was no basement: Howard suspected "that such a large area below grade would eventually be used for patients."

999 Queen's name would change often, to fit the changing times. In 1871 it became the Toronto Asylum for the Insane; in 1907, when Graeme L was there, the Toronto Hospital for the Insane. From 1919 to 1966 it was called simply the Ontario Hospital. Further monikers, similarly motivated, would come later.

But it remained to most Torontonians simply "Nine ninety nine" -- civic code for the nut house, the loony bin. Bad boys and girls were ever warned: "You'll end up in 999!" It might well have been "666," the Mark of the Beast, turned on its head.

|

Touring rot

999's director & chief engineer make their case with squalour in the Toronto Star, Dec 16, 1975. Below: opponents in The Globe & Mail a week before, inside just briefly -- & voluntarily.

|

Turfing history

999 now, as 1001 Queen Street West (the ghost of its 2nd-last name still barely visible). Far right: its latest moniker.

|

|

By 1956 the long wall on Queen was gone. A new structure fronted the old Asylum, masking it from the street. In 1966 it got a sanitized name: The Queen Street Mental Health Centre. And a new address, meant to wipe clean the historical memory of horrific "Nine ninety nine": 1001 Queen Street West.

John Howard's vision had indeed become a horror. His vaunted plumbing had served just "ten water closets, and eight baths, sinks and cisterns," privies on the grounds and pots in patients' rooms long in use. As early as 1853 the air was foul; there were epidemics of dysentery and cholera.

Their deeper cause was found that year: a planned sewer pipe had been left out. Stinking refuse and rotted floor joists were dug out and carted off by the ton. Rats were common: one patient in 1907 said she didn't want "to stay in bed for the rats to eat." She was not delusionsal. A major renovation in 1920 got more plumbing in; it did not get rodents out, still reported there, by its director, in 1923.

Meant to house 264 patients, the main building opened with 308. New wings ran south in the 1870s; patient "cottages" (actually massive 3-storey houses) went up, more buildings in the 20th century: always, the Asylum was overcrowded, 1,800 people once housed there, patients kept even on the verandas.

In 1975 the Asylum's provincial masters said they'd tear it down, citing its "stigma" and saying "the old building just doesn't fit in with the master plan." The director led press tours of its decaying rooms. Heritage activists, who'd seen it all before, cried foul. Architect Jack Diamond came up with plans for its use as office, not patient, space.

Taking a cue from civic action that had saved a Victorian row on Sherbourne just two years before, some 50 protesters twice occupied the building, wreckers already in. A photo on The Globe and Mail's front page, December 8, 1975, showed some inside: city councillors (one, John Sewell, later mayor); teachers and students of architecture; citizen activists who had saved Old City Hall and Union Station.

This time, heritage lost. And to some relief. On a wall of one ratty room its inmate, there just a year before, had scrawled: "Sorry to see you go." But another, told the "Old Girl" might be renovated, said: "Does that mean I'll have to go back?"

Where 999 once stood, there is now a parking lot. The sign out front, at 1001, reads "Centre for Addiction and Mental Health," Queen Street site of a new service born of a 1998 amalgamation with the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry (named for a later 999 director) and the Addiction Research Foundation.

As John Bentley Mays noted in Emerald City: Toronto Visited -- in a chapter called "Moral Management": "Today, there is almost nothing left of Howard's edifice or its message," but for the remaining walls east, west, and south. The place has a new look: "less one of asylum than of community college."

-

"Low dormitory towers are connected by glassed-in walkways, bordered by parking lots and tennis courts and grassy lawns. There's even a pleasant student union building -- it's called the 'community centre' -- with a large central lounge, a swimming pool, a coffee shop, a bank."

|

Campus clean-up:

999's site gone to cars -- & yet another new name.

|

Architecture sends messages. The campus at 1001 Queen says, as J B Mays put it, that "the asylum as prison is nearing the end of its long career, and that soon all the insane will 'graduate,' walking out to resume life as productive and happy and creative citizens." But he also says:

-

"Reality and architecture are usually different, with architecture playing the role of making rhetorically forceful the myths and theories reality stoutly denies."

In 1975, I was among those occupiers of 999 (on the steps, left, in that Globe photo above). I had written the Star -- its editors, as ever, boosters of civic progress: "Shouldn't society demand of those who wish to tear things down proof that they will be replaced by something more socially valuable, something that will truly compensate for the loss?"

1001 Queen West's "campus" surely does not. As architecture. That's all our gang was on about then (if mindful of broader, and fragile, urban fabric), our occupation voluntary and safe: the door we'd broken in though had been cracked by Alderman William Kilbourn. We could leave 999. And, of course and politely, we did.

We knew little, beyond rumour, of the lives of people who could not.

|

People, not "cases"

Geoffrey Reaume's Remembrance of Patients Past, on its cover Audrey B, 1937, at age 71. Confined from 1905 to her death in 1946, she worked 30 years in 999's sewing room: there she could be "my wonderful self."

|

Worlds a wall apart

999's east wall, on Shaw St, likely built by patients. Few would have seen the ordinary life of the street just feet away. Further below, the inside seen from unwalled Queen (sign: "Dogs must be kept on leash").

|

|

-

"Oh that I had wings I would fly like

a dove and be at rest I would fly out

of this asylum.... "

-- Ralph H, "Husband, Father, Farmer,"

his life from 1898, age 57, to his death in 1911,

spent at 999 Queen Street West

Graeme L, his 1907 poem on walls farther above, was 47 years old when admitted to what was then the Toronto Hospital for the Insane. He wrote other poems while there, discharged six months later.

In 1976 Geoffrey Reaume, age 14, was admitted to the Regional Children's Centre in Windsor, Ontario, as a psychiatric patient. He stayed three and a half months. In 1979 he would spend ten weeks in the St Thomas Psychiatric Hospital. He would see seven years as a psychiatric outpatient. His diagnosis was among the most common -- and least defined -- in all of psychiatry: schizophrenia.

Geoffrey may have written then. He certainly did later -- as a graduate student in history at the University of Toronto, where he studied the history of experiences much like his own.

- "Too much of what did exist seemed to be based on a stereotype of people in mental institutions as either incapable or violent, devoid of any sort of complexity in personal relationships with one another, a monolithic group of people without much of a life beyond a diagnostic label."

He thought: "Why not try something different?" His doctoral thesis became a book, published in 2000: Remembrance of Patients Past -- patients at 999 Queen Street West, from 1870 to 1940.

Geoffrey Reaume dug deep in the case files of 431 patients at 999. Of these, 197 appear in his book. As persons -- not "cases" -- some "only in fleeting references, others through detailed portraits" based on official records and, where surviving on file, their own works: letters, diaries, drawings, and poems.

He discovered daily routines, ongoing relationships; evidence of patients' limited leisure and personal space, of their diagnoses and treatments. Many spent decades there; some, most of their adult lives. Many died there: 5,718 of the 22,475 people admitted up to 1940.

He also found them working -- not on their own works, but 999's. Patient labour had long been part of "moral treatment," for some with good effect. Audrey B, a domestic servant admitted in 1905, worked in the sewing room for 30 years, fretful when she missed a day. There she was quiet, but for occasional remarks on "my wonderful self," others there surely glad for the company of "such a lovely lady."

But labour could also be forced: by promise of favours, or by shaming of "laziness." Patients cleaned wards and halls, served in kitchens and dining rooms, washed and ironed literally tons of laundry: in 1905 patient labourers, 86% of them women, processed 409,868 soiled pieces. Men worked the soil, much of the Asylum's ground gardens. They even worked its walls, up to 3,000 feet built by patients in 1889.

None was paid. One women in "a mania to scrub floors" felt she had to, in return for her institutional clothing. Moral treatment through modest labour, originally kept light, was meant to ease boredom and foster self worth: "The benefits patients derive from this," said a report of 1896, "cannot be overestimated."

Neither can the financial benefit, to the Ayslum, of what would come to be called "industrial therapy." That report's very next line: "if outside labor were employed, it is obvious that the expenditure would be largely increased." The annual report of 1889 touted "tens of thousands of dollars saved" by patients working on the very walls that confined them.

Geoffrey also explored how they got there. What did they do to warrant the social stigma of "lunatic"? What had deemed them fit candidates for involuntary commitment to the madhouse?

Quite often, not much. Some had been violent, if far from most -- certainly not enough to deserve mass stereotype as "raging psychopaths." More had been driven to rage just short of violence (but, too often, against themselves). Many more had been deeply withdrawn, reticent, depressed.

What they shared was a sense -- among fellow citizens, families, doctors, judges, policemen, and in time social workers -- that they were, if not actually violent, then certainly aberrant. Their odd ways were often a burden to friends and loved ones, to others offputting at best: unconventional; unpredictable; unsettling. They were disturbing -- therefore "disturbed." And maybe dangerous.

In 1895, Samantha C was deemed insane by a doctor who observed "taciturnity and an indisposition to exercise and a general appearance of mental aberration." Daniel Clark, then Asylum director, questioned the doctor but got no reply. Samantha died in 1921, at 999. In 1878 Ellen G, age 40, mother of seven, was committed after being violent at home. Admission papers noted her claim that "her husband is the source of all her sickness"; she feared being poisoned. She was deemed delusional. Ellen died 40 years later, at 999.

James D was admitted in 1907 after his wife said he'd been "acting strangely ever since he began studying socialism." Records do not indicate that his doctors found this irrelevant to his diagnosis: "manic depression." He was released, "recovered," a few months later.

Frank I, 28, unemployed, harassed over his German name, his parents' windows smashed, wrote a threatening letter to Governor General Lord Aberdeen in 1897. He was arrested, in early 1898 committed to 999 -- where he claimed royal descent and liked playing the piano. Daniel Clark recalled him as a "poor fellow, gentle by nature." He died in 1907, at 999.

Some ended up at 999 for simple want of anywhere else to go. Another James D, Irish immigrant and single, "a poor uneducated laboring man," was admitted in 1896 from the York County Gaol. He'd been "a regular frequenter," arrested for vagrancy. He died at 999 in 1914.

"Lovely lady" Audrey B, losing a job, later in residential care, had been released "to run the streets ever since with no person to care for or treat her." She was arrested in 1905, ending up in 999. Her admission report says she "guessed it to be a place where they put things right, yet did not know what was wrong -- nothing wrong with her." She spent the rest of her life there, dying in 1946.

In an age without social support, beyond charity, for the unemployed working class or the homeless, the Asylum was often the last refuge. Governments were happy to dump them there, hoping as Reaume says to "cut back on social expenditures."

The aberrances deemed most disturbing, even if not violent (most in fact not), were those seen linked to sex. Or as we'd now say, gender. Of women locked up at 999 prior to 1900, a quarter were in for "female trouble" -- "childbirth, lactation, miscarriage, menstrual disorders, uterine disorders" and other natural conditions seen as "the predisposing cause of insanity."

The "wandering womb" lived on in medical discourse. Cynthia H, 49 -- widowed and childless, admitted to 999 from a sanitorium in 1904 -- was "reported to have been restless, terrified of being deserted by everybody," and "in constant dread" of not being provided with food. The cure for her "hysteria"? A hysterectomy. It failed to cure. She died five years later, at 999.

Daniel Clark denounced sexual surgery -- as an attack on "women's innate sense of modesty." But "utero mania," as he called it, was common: countless women were unsexed "for their own good." Many more went not under the knife but into the bin -- for the good of "the race."

|

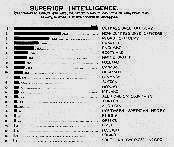

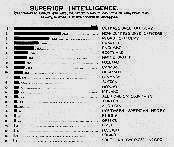

"Superior Intelligence"

The US Army charts its smarts, c 1918: Commissioned officers tops, NCO's next, "Negro officers" 3rd, "Southern American Negros" last (& Poles 2nd last).

|

|

Nothing more threatened the forces of racial purity than "loose women" of the working classes. As Reaume writes: "The confinement of lower- class females who engaged in sexual relations outside of marriage could begin as soon as the local authorities became aware of such behaviour."

Madge M, a 38 year old servant, Catholic and single, had two children by different men. In 1904 she was in the York County Gaol. Its doctor begged the Asylum to take her: to keep her from giving birth "to more unfortunates of her own kind to be a burden to themselves and the State." Sent to 999, she died there in 1916. Marcia F, admitted in 1876, had been repeatedly confined since the age of 15, her jailers' sole justifcation that she had frequent sex with different men.

Worse: she liked it. Marcia "spoke freely" of her sex life: she was "lacking in the usual womanly modesty and sense of shame"; she was "always crazy after men." Marcia spent 12 years at 999, dying at the Cobourg House of Refuge in 1918.

Women like Marcia and Madge were seen as "hypersexual" (especially if they were "crazy after" other women). "Wayward females" were lumped in with "half wits," "idiots," people of "low intelligence for their age" (and epileptics) as eugenicists' most dreaded threat to the purity and advancement of the race: "the feeble minded." Geoffrey Reaume quotes Angus McLaren, 1990 author of Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada, 1885-1945:

- "For the middle class, of course, it was a comforting notion to think that poverty and criminality were best attributed to individual weaknesses rather than to the structural flaws of the economy."

Charles Kirk Clarke, 999's director from 1905 to 1911, was on the forefront of efforts to "keep this young country sane." In 1907 he denounced "the evil results of the addition of defective and mentally diseased immigrants to our population," penning a learned article on "The Importation of Defective Classes."

Sex brooking no risk of tainted conception could also get people locked up. Masturbation, ever suspect in society's moral collapse, featured in diagnoses at 999: it was thought to render men "idiotic." Homosexuality was of course a crime. Some psychiatrists had begun to contest that, finding it more humane to see "the homosexual" as mentally ill.

Asked to assess the state of a 36 year old gardener arrested for sex with three young men in a laneway off Yonge Street in 1926, one was happy to conclude: "I have no hesitation in giving the opinion that [he] shows symptoms of incipient lunacy." That gardener may have been spared prison. He was likely not spared the bin.

The Asylum, ideally a refuge from the wider world, was in fact the world in microcosm. Especially the world of class. Most patients were working class or worse off: indigent, abandoned, abused. They were there largely because of their place in the margins of a world better off.

But some better off were there too. There were private rooms, decently furnished; "middle class" rooms for $4 to $6 a week. The best off were those who could count on outside support (Geoffrey Reaume emphasized its value, and often: his family ever stuck by him). Felicity A T, at 999 from 1894 to her death 30 years later, lived many of those years as "Angel Queen XIII" -- royally decked in outfits she made herself, with materials brought in by her husband and daughter. She also made clothing and banners for other patients, her "Angel King" in particular.

Felicity's noted "force of character" made her 999's most famed patient, indeed Queen of the Asylum. But she was lucky. Other middle class patients, especially as they aged, saw family support fade away; demoted to cheaper quarters, usually shared, they might end up in an 18-bed room on a public ward. Some, and many not well off when admitted, made what lives they could in the corridors. In the laundry room their work included the duds of their lucky "betters."

The people most abused in the world outside -- "hysterical" women, "delinquent" teenagers, the very old or very queer, "foreigners," the physically disabled -- would not find true asylum. The most aggressive staff were sometimes "made an example," most often when abuse was witnessed by visitors.

But, as Geoffrey Reaume says, "daily degradations experienced by patients were part of routine operating procedure at every level of the asylum." The petty tyranny of individual nurses or attendants might be caught out; rarely was the deeper abuse beneath. Degradation was inherent to the system.

An "expert system." The experts, untouchable, were doctors.

|

Doctors "both divine & satanic"

Joseph Workman, first director of 999, fan of fresh air. Below, C K Clarke, 1907: mad for "schizophrenia."

|

Doctors' orders

Psychiatry's treatments, historic & (since the 1920s) "heroic"

Moral therapy:

Emphasis on natural healing, fresh air, generous diet, cleanliness & "respectable" behaviour.

Restraints:

Chains, crib beds, face masks, handcuffs, legcuffs, four point cuffs ("spreadeagling"), straitjackets, solitary confinement.

Hydrotherapy:

Immersion for 4-6 hours in temperature controlled tubs, often cold.

Cold wet pack:

Restraint by wrapping in wet sheets.

Drug injections:

Salvarsan & manganese chloride, for patients with syphilis. Ineffective in treating deep brain damage.

Malaria:

Induced, to cause therapeutic fever in syphilitics. "Spinal drainages reported."

Fever cabinets:

High heat therapy, body enclosed.

Insulin shock:

Doses up to 275 units, 6 times a week over 2-3 months, to induce hypoglycemic shock: convulsions; "noisy excitement" (screams); coma after 3 hours. Revived by glucose, often given by gastric nose tube. Often led to amnesia; sometimes to permanent coma & death.

Metrazol:

To induce coma, leading to "more severe complications" -- Reaume says "most likely referred to fractures."

Psychosurgery:

Lobotomy, or leucotomy: isolation or destruction of selected brain tissue, by electrodes, sonic treatment, radiation, or leucotome ("the ice pick"): a probe with a spring- loaded blade stuck though a hole in the skull, often in the orbital bone -- got to between eyelid & eyeball.

Aversion therapy:

Pain (from noxious drugs, shocks) inflicted in connection with stimuli, often sexual, deemed inappropriate; pain relief paired with acceptable "object choice." Used to "cure" homosexuals; & on "retarded" & "autistic" children, some in institutions zapped with electric cattle prods.

Electroconvulsive shock:

See below.

Adapted from a glossary of "key terms used by mental health professionals," in Shrink Resistant.

|

Credentials

"You need professional help."

|

|

-

"...it was thought, and by the patient first of all, that it was in the esotericism of his knowledge, in some almost daemonic secret of knowledge, that the doctor had found the power to unravel insanity..."

-- Michel Foucault in "The Birth of the Asylum,"

from Madness and Civilization, 1965

The handful of men who ran 999 Queen over the years had varied takes on the treatment of those in their charge. But they did have one thing in common: immense power over thousands of lives. Lives vulnerable, often fragile -- and at the mercy of their mystique, as doctors.

In most tales of the Asylum its first directors, Joseph Workman and Daniel Clark, are the good guys. Compared to some later, they were. Workman banned physical restraints in 1883 (but they were sometimes used anyway, and often still are). Clark scorned "utero maniacs" putting the knife to defenceless women (if some were still unsexed). He saw good nutrition as a necessary step on the road to sanity, bringing in free dentists in 1898 to help patients eat better (but there were no dentists on staff until 1931).

Both were good men of their time. And class. Their work was intended, Reaume says, "to promote essentially middle- class standards of conduct ... ideas about respectability and a regular daily routine." And they followed Phillipe Pinel, who followed John Haslam's 1798 "practical remarks on insanity":

-

"The keeper of madmen who has obtained domination over them directs and rules their conduct as he pleases; he must be endowed with a firm character, and on occasion display an imposing strength. He must threaten little but carry out his threats, and if he is disobeyed, punishment must immediately ensue."

Pinel's "habitual punishment" was a cold shower, to "subjugate insane persons" and "conquer obstinate refusal." Much firmer subjugations would find invention, their stated goal to treat the mind. But their first aim was to subjugate the body.

The intent was to create what Foucault called "docile bodies" -- bodies "that may be subjected, used, transformed, and improved"; bodies easy to manage, study, and control: long the objective of efficient generals, jailers, captains of industry and, as we'll see, psychiatrists.

"Correct classification" of the insane, Daniel Clark said in 1898, "is impossible." His successors would find his view insufficiently "scientific." C K Clarke (he of the Clarke Institute, not to be confused with Dr Dan), arriving in 1905, insisted on rigid categorization of the nebulous ills called "madness."

They were dissected, diagnosed with empirical precision, each neatly labelled in scrupulous Latin or Greek, the names invented by a German named Krapelin. The day's reigning favourite: dementia praecox -- sounding rather more sinister than one possible, and likely relevant, translation: "precocious folly."

It got helpful adjectives: "hebephrenic" (Hebe the Greek goddess of youth), for "unsystematic behaviour" or "inappropriate emotions"; "catatonic" for stupor; for the fearful: "paranoid." Later it was called schizophrenia, Greek for "split mind." ("Paranoid schizophrenia" had been Geoffrey Reaume's second diagnosis.)

By 1908, Clarke could confidently assign those in his charge to their "correct" category. Some 7% had manic depression. Another 4% melancholia, general paresis (chronic paralysis of syphilitic origin), or senile dementia. Half as many suffered "imbecility," epilepsy, or alcoholism.

Fully 55% he diagnosed with dementia praecox. Just later, the average for other Ontario asylums was cited at 25%. C K was clearly a fan of "schizophrenia."

Categorization, Michel Foucault once said, is colonization. The first step in controlling people is finding the right box to contain them. But it had a more vital purpose for psychiatrists of the day: to win professional credibility -- as scientists. Jacalyn Duffin writes:

-

"Anesthesia, antisepsis, germ theory, and public health had fostered effective interventions for other human problems. ... Psychiatrists, on the other hand, had yet to make equivalent discoveries -- discoveries that could explain, predict, cure, or prevent."

They were desperate to prove psychiatry a legitimate branch of medical science. Their focus turned from the nebulous mind, suspended in a web of complex and vital human relations, to the concrete brain: an organ -- a mechanism -- isolated in separate bodies. Minds, they had failed to grasp; brains, or the bodies that housed them, they could get their hands on. Their tools -- probes, blades, electric shocks, neuroleptic (literally "nerve seizing") drugs -- would soon invade the brain itself.

They pursued credibility not only by supposed medical rigour, but by taking on the trappings of medicine: intensive investigation; definitive diagnosis of "diseases" clearly named; and, famously, the collection and publication of "case histories."

Their patients' lives -- their actions, character traits; their unique personalities -- were reduced to symptoms fit for generalization as evidence of a classic "case." In "The Case of the Case," Steven Maynard cites Julia Epstein's Altered Conditions: Disease, Medicine and Storytelling: "Case- taking did not become a formalized or systematic procedure until it became connected with clinical schools and institutions and the need to produce and codify a professional discourse."

The discourse, and power, of all "helping professions" is deeply rooted in case histories. Doctors, lawyers, social workers, the police (Steven's case in point: "The Emergence of the Homosexual as a Case History"); all gather, study, and spread their stories around -- as "popular knowledge."

Professionals promise "expert" services; quite often they deliver. They also serve themselves, disparaging "uncredentialed" helpers as "amateur" (the word means doing it for love, not money), mystifying knowledge as their private preserve -- and looking out for each other. Professional mystique can be perfect cover for a middle class protection racket.

Some of us, by education or status, are positioned -- class positioned -- to tap the expertise of the expert class while resisting surrender to its mystique. (It helps to have helpers who understand -- and reject -- professional mystique.) But many of us are not. The Asylum's patients met in the experts who ran their lives, Geoffrey Reaume says, "an arrogance that was overwhelming."

Doctors had the power to tell their charges what they might do and what not, when they would eat, when they would sleep, what they would wear. Few later inmates of "total institutions" (prisons, hospitals, and the military also among them) would have Angel Queen's freedom of attire. Personal effects -- personality itself -- do not make for "docile bodies."

Doctors could censor patients' letters, or confiscated them "'for their own good,' to prevent them getting upset about their contents after recovery." Geoffrey found patients' letters in their files, preserved for history -- if lost to the people for whom that caring, even sanity fostering, connection was meant.

They could keep their charges locked up for life; they could abuse their bodies in the name of healing their minds. They could do it simply because they could. They were experts, professionals, doctors "both divine and satanic," Foucault said, "beyond human measure in any case."

When the deepest questions are answered by ideology -- pervasive, invisible, inevitable ("progress," "efficiency," "mental health," "master race") -- we are free to focus on means, not ends: how, not why. We can get lost in modern culture's most gripping obsession: technique.

Doctors of the mind did -- with a vengeance madly inventive, ever refining their techniques (as you've seen above). Their efforts were "heroic" -- or so their press agents and later hagiographers have told us. Their patients were mere fodder: docile bodies, unsettled minds -- probed for "knowledge" by unsettling them even more.

Professional assault was massive, brutal, chaotic. Even total: minds swept clean of memory, ability, personality, personhood itself. Maybe forever.

|

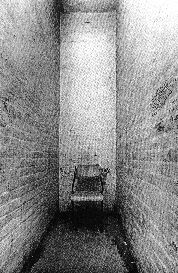

Breaking the box

Cover illustration from Shrink Resistant: The Struggle Against Psychiatry in Canada. Above: solitary confinement cell at the Don Jail.

|

Shock docs

"Heroics" (continued)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT):

Electric current, 130 to 175 volts, zapped through the brain for 0.1 to 1.5 seconds, 6 to 12 times in a series, repeated 15 to 35 times.

The subject can't eat or drink 4-6 hours before, may be given sedatives to "reduce fear & resistance," then Atropine for the heart, an IV anesthetic, & a muscle relaxant to reduce risk of fractures. Electrodes are stuck to the temples, spread with jelly to prevent burns.

The shocks cause grand mal seizure -- sometimes with cardiac or pulmonary arrest -- then brief coma. Subject awakes to possible vomiting, irregular heartbeat, amnesia, delirium, & "wild excitement" checked by drugs or physical restraints. Longer term side effects can include "reduced intellectual function, emotional blunting, loss of creativity, energy & enthusiasm," prolonged amnesia or permanent brain damage. Some shock

"treated" have lost longtime skills, even the ability to recognize the faces of their own families.

Doctors don't know how electroshock "works." But they are sure it does -- producing the effects they desire.

|

|

-

"Psychiatrists don't know what 'schizophrenia' is, and don't know how to diagnose it. ... the ceaseless manufacture of disease names in psychiatry, together with a total lack of evidence of them -- from agoraphobia to schizophrenia -- is the greatest scientific scandal of our scientific age."

-- Thomas Szasz (author of The Myth of Mental Illness),

in Schizophrenia: The Sacred Symbol of Psychiatry, 1976

"The fact is that virtually every human emotion, every kind of behaviour and every way of perceiving things can be found listed under one disease or another in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual -- psychiatry's disease bible."

-- Irit Shimrat, in Call Me Crazy: Stories from the Mad Movement, 1997

"It's like the system is trying to turn everybody into vanilla, and maybe when you went in, you were chocolate almond swirl."

-- A former psychiatric inmate, in Call Me Crazy

"One in ten Canadians will suffer mental illness in some form at some point in their lives." That statistical "fact," lately blared on TV, in magazines, on billboards (a friend recalls it as "one in five"; I can't now confirm), is in fact professional promo. As Irit Shimrat writes:

-

"The concept of mental illness is a powerful and useful one. It generates a great deal of money not only for drug companies but also for psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists, social workers, mental health bureaucrats, hospital staff and community mental health workers. It also deters people from taking a hard look at what's really wrong in the lives of those who are in emotional trouble."

Those of us (million in Canada we're told) who risk not being vanilla. "What if 'normal' functioning," Irit asks, "can sometimes be achieved only at the expense of creativity and critical thinking? What if social norms need to be changed in order for the world to be a better place?"

Irit Shimrat calls herself "an escaped lunatic." She is among many who reject the status of "patients treated in hospitals," even rejecting the terminology. They were inmates: incarcerated; imprisoned; often abused and sometimes tortured -- "for their own good." They now define good on their own terms, finding collective voice as ex-inmates, escapees, the resistant "psychiatrized." The Mad Movement.

They have refused professional labels, enforced confinement, imposed isolation; they have broken the box of diagnostic classification, throwing off their fetters as Pinel cast off chains. But, unlike Pinel's insane, they have delivered themselves. And each other. Irit Shimrat dedicates her book to them: "heroes, one and all."

"All my life," Irit Shimrat says in Call Me Crazy, "people have been telling me I'm weird." She "went crazy," as she says, "in 1978 and again in 1979, and was locked up in a total of three psychiatric facilities, ending in 1980." From the last one, she escaped.

Her mother, afraid for her at first, felt she'd done the right thing. Her father had left a small estate; lawyers doled out $150 a week to Irit. She took a room in downtown Toronto and tried to find a life. In time she found people who, if still sometimes finding her a bit weird, were pretty weird themselves.

At least by vanilla standards: many worked, most unpaid, on The Body Politic. Some shared digs at 97 Walnut Avenue, "Harmony House," dyke dynamo Chris Bearchell perennial den mother there to a close if slowly shifting crew. (Dispersed, the Walnuts remain linked in activism via their cyberspace domain, Walnet.)

I knew Irit then, at The Body Politic and at Walnut, that menage not unusual for the likes of us: various group households had long bred social activists; Chris saw some earlier, one on Caroline Avenue in South Riverdale. There were many more; as I've since said: "It's how we raised our kids." Irit, you could say, was one of them. If, like all of them, no mere kid.

-

"The years I spent at Harmony House, as it was ironically called -- and, in particular, my connection with Chris Bearchell -- constituted the most important part of both my political development and my recovery from psychiatric treatment."

As a psychiatric escapee in 1980, Irit hadn't known she was one of many ("I would have felt less alone") -- nor that some constituted a political movement. In 1986 she found a classified ad seeking an editor for Phoenix Rising: The Voice of the Psychiatrized. She got the job, joining Don Weitz, Bonnie Burstow, and other ex-inmates on its editorial collective.

Bonnie had joined others to form the Ontario Coalition to Stop Electroshock in 1983. Invented in 1938, "shock treatment" rose along with lobotomy, born just before, to rank as psychiatry's most "heroic" technique. More than 50,000 people were lobotomized in the US, some 1,000 in Ontario from 1941 to the mid '60s.

The "ice pick" fell out of fashion (if "laser" lobotomies have been reported since). Shock did not. In late 2001 a doctor at Riverview Hospital in Port Coquitlam, near Vancouver, was fired "for blowing the whistle on 'greedy' colleagues" padding their pay by "performing needless electroshock therapy" on elderly patients.

Riverview's director said he'd been let go not for tattling but in a "restructuring," adding: "There was a full review of ECT last year, and the program was recognized as a good one ... and continues to be used where appropriate." Since 1996, doctors have been able to bill the provincial health plan $62 per ECT; before that they got nothing for it beyond salary. More than 10,000 were done in 2000, most on "depressed or demented geriatric patients."

Electroshock, in use for some 60 years, is still an "experimental treatment." Its lab rats are human beings "scientifically diagnosed" with depression, apathy, hostility, agitation, negativism, anorexia, schizophrenia -- and "lack of insight." That last diagnosis doctors often apply to those refusing to admit that they're sick.

If you're sick: take a pill. Even if you're not sick -- simply driven mad by the pace of modern culture -- take a pill. Mood swings keeping you from settling down to "functional" normality? Try Valium (long called "the housewife's drug"). Kids driving you crazy? No time for that: give 'em Ritalin. Want to get happy? Get Prozac. Life got you down? Sorry dear, that's life. Can't change life. Just take a pill and get over it.

We are a culture addicted to corporate pharmaceuticals. The avid War on Drugs never touches the War of Drugs -- on daily life. Especially the lives of "the mad." Psychiatry is now convinced that most emotional upset is rooted in physical illness of the brain. That it is neurological, biochemical, even genetic.

The human brain is the most complex structure known to science. Or rather, mostly not known. And brain function by itself is surely less than the social phenomenon of mind. But, as ever in science madly obsessed with technique -- practical results, "magic bullets," the quick fix -- a little knowledge (despite the old adage) is a convenient thing: it justifies massive chemical warfare.

The psychiatrized now face daily dosing: neuroleptics (Stelazine, Thorazine, Haldol, Clorazil, Zyprexa, Risperdal); "mood stabilizers" (Depakote, lithium); antidepressants (Nopramin, Tofranil, Elavil, Nardil, Effexor, Paxil, and Prozac); uppers (Benzedrine, Dexedrine); "anti anxiety" downers (Ativan, Rivotril). And other drugs to counter the unforeseen side effects of this cleverly tradenamed pharmacopia: tremor, rigidity, asphyxia, even heart failure; a friend of mine says they should all be called, simply, "effects."

The drugged may now also face an entirely new diagnosis: tardive dyskinesia -- "various uncontrollable and grotesque movement of the body, primarily the face, mouth and tongue" -- caused by prolonged use of neuroleptics. It strikes up to 50% of those taking them, millions of people worldwide.

Those hoping not to join their numbers often have no hope. Treatment orders, given the force of law in Ontario in the late 1990s, turn people who refuse daily dosing into the criminally insane, a "danger to the community."

That's where many end up. Governments once eager to cut costs by warehousing the troubled in cheap asylums now (progressively) want them "in the community." Chronic patients are dumped out on the street, to whatever community services they might find -- few, and chronically underfunded, as they are.

Parkdale, in the western shadow of 999 turned 1001, has long been a psychiatric ghetto, its rooming houses and cramped bachelorettes home to the mandatorily medicated. There, the Tories' Community Treatment Orders go by a shorter name: The Leash Law. Failure to follow doctors' drug orders gets the recalcitrant "mad" yanked back to the bin.

|

"New" Asylum; new line

LGBT -- OK! The Centre's trademark squiggle is maybe meant to be more uplifting than the former Clarke Institute's logo: a mad EEG wave finally calmed -- to flatline.

|

|

Until 1973, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual confidently listed "homosexuality" among its myriad "mental disorders." That year the American Psychiatric Association -- professional protection racket of doctors who had long shocked, lobotomized, or therapeutically "averted" thousands of men and women in attempts (usually failed) to "cure" them of "inappropriate sexual object choice" -- changed its mind.

Prodded (even "zapped") by the growing gay liberation movement, the APA admitted that "a significant proportion of homosexuals are apparently satisfied with their sexual orientation," showing no signs of "manifest psychopathology." For those not "apparently satisfied" they invented a new diagnosis: sexual orientation disturbance. They still needed treatment, perhaps for their "disturbed" sexuality.

Or -- for internalized "homophobia." That term dates from 1971, first used in a journal of psychology. It was popularized by Dr George Weinberg, in his 1972 Society and the Healthy Homosexual. His profession: psychotherapist.

Taking a look around 999 (sorry: 1001) in the summer of 2001, I could not help notice a banner out front: The Centre "Celebrates LGBT Pride." Proud even to carry a pink triangle once marking inmates of other institutions. Run by Nazi experts.

Liberation triumphant? Grim history, learned from, at last overcome? Don't count on it. Like so much else about the "new" Asylum, that banner is evidence of eager efforts to wipe history clean. To render it safe, nice, innocent of official malice.

"Homophobia," you'll note, is a phobia. An irrational fear, a neurotic disorder -- personal, not social. It is also, now, common coin: everyone of progressive bent takes pains to excoriate "homophobes." To paraphrase Angus McLaren on past middle class perceptions of the "feeble minded": For good liberals, of course, it is a comforting notion to think bigotry and abuse are best attributed to a few sick minds, not to the structural flaws of society.

More perceptive social critics, many feminist, prefer "heterosexism." Academics often use "heteronormativity" -- rather a mouthful if making plain the true issue: not personal phobias, but pervasive social norms. Ideological norms, as ever invisible, inevitable, presumed merely "natural" -- even by the most avid scolder of crude and uncultured homophobes.

And note whose Pride is blithely celebrated on that banner: "LGBT" -- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual; all the correct categories. Well, nearly all: those more eager to tout their "inclusiveness" tack on Transgendered, Two Spirited, Others of various "alternative lifestyles." I've lately seen "LGBTTO+" -- varied, vibrant lives bureaucratically reduced to a single graceless acronym; the creation, liberally motivated, of ever new classifications: distinct, statistical, even socially "scientific" -- more diagnostic than descriptive of who we, as people, might truly be.

Too many of us (even, perhaps especially, "LGBTTO+" us) are happy to think like the helping professions, madly classifying ourselves and each other. Even in the name of Rights and Equality, we speak the language of social control.

-

"The first and second times I went mad, I got professional help -- hospitalization and drugs -- and stayed crazy for months. The third time I got help from a friend who wasn't scared by what was happening, because she'd been there herself, and it was over in a few hours."

-- Irit Shimrat

Our everyday lives are ever more in the grip of commercial control. Want meaningful talk? See a counsellor. Casual connections? Try a dating service. For every need there's a service, an expert, a product -- for a price. You get what you pay for. Or so we're told.

We risk losing human connections -- friends, comrades, "amateur" sources of help and support, the people in our lives every day -- as what they can truly be: a gift. As Bonnie Burstow and Don Weitz wrote in Shrink Resistant:

-

"Community arises from meaningful encounters with other people. ... With the discovery of community, the task of keeping oneself together turns into a task of mutual support. An impossible task in an impossible world turns into a task which all of us as family can achieve."

Some of us, some of the time, may feel we're "going crazy." We may need support beyond the means of everyday life and loves. "It is also true," Geoffrey Reaume says, "that, at times, involuntary committment to a mental health facility was and is today still necessary for those who are a physical threat to themselves and to those around them."

Forced confinement, even for a time, is a fate few of us imagine (if some know too well). But psychiatry can set a more lasting sentence. It can demand, as Irit says, "learning to believe that you're damaged good, less than other people, defective."

-

"That you're not okay, and you'll never be okay, but you can be more like other people. To get there, though, you may need all kinds of treatment. ... Once you're diagnosed, they've really got you. Laugh too much, cry to much, talk too much, don't talk enough -- or, god forbid, get angry -- and the people around you think you're getting 'sick' again."

Worst of all: "you're taught not to believe in or trust yourself." Nor to trust anyone in your life but "experts." Their heroic techniques and scientific labels are deployed "for your own good." So dear: Be good.

Even if that means you may end up -- for good -- something less than human. Such "treatment," as Irit Shimrat says, "has got to stop."

See more on:

The modern world's panopticon, in Private property; public life, a Downtown side tour of the Eaton Centre & PATH; & police surveillance in Urban amenities; erotic anxieties.

More "problem girls," bad boys, & moral policing to check their fall, in Mad for 'the show'.

Saved heritage more noble (if no more historic) than 999 Queen, in

Dreams of grandeur &

Halls of law & governance, both Downtown side tours; &, east of downtown in Master builders meet citizen activists.

The Mad Movement, at "Escaped Lunatic" Irit Shimrat's website: The Lunatics' Liberation Front. See Irit, Chris Bearchell & other Body Politic veteran dinosaurs on "The Jurassic Park Cruise" in Promiscuous Affections, 1993.

The Walnuts, at Walnet (www.walnet.org). For other group households as hothouses of social activism, see: Promiscuous Affections, 1977; "Baby steps" in On the Origins of The Body Politic; & "Sky Gilbert & Buddies in Bad Times Theatre" in Diva Diaries.

My own brief encounter with a young man who did "end up at 999" -- & how easily one might -- in "Visitation: Michael of the Vans", Episode VII of Angels: Twelve Episodes.

My thanks to Irit Shmirat (now living in British Columbia, where she has regrettably since seen the inside of some of that province's finer institutions) for review of this piece in draft, offering corrections, additions, many invaluable comments -- & her sharp editorial eye.

Sources (& images) for this page: Eric Arthur: Toronto: No Mean City, University of Toronto Press, 1964 (street view of 999 Queen W).

Eric Wilfred Hounsom: "An Enormous Building for its Time," in Journal of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, Jun 1965; & Toronto in 1810, Ryerson Press, 1970.

Michel Foucault: Madness & Civilization, 1965; & Discipline & Punish, 1977 (excerpted in The Foucault Reader, Paul Rabinow (ed), Pantheon Books, 1984).

Mike Filey: Toronto City Life: Old & New, Nelson, Foster & Scott, 1979 (York gaols & Toronto jails).

John Marshall: Madness: An Indictment of the Mental Health Care System in Ontario, Ontario Public Service Employees Union, 1982.

Allan Chase: The Legacy of Malthus: The Social Costs of the New Scientific Racism, Alfred A Knopf, 1977 ("Superior Intelligence").

Gary Kinsman: The Regulation of Desire: Sexuality in Canada, Black Rose Books, 1987.

Bonnie Burstow & Don Weitz (eds): Shrink Resistant: The Struggle Against Psychiatry in Canada, New Star Books, 1988.

Frederick H Armstrong: A City in the Making: Progress, People & Perils in Victorian Toronto, Dundern Press, 1988.

William Dendy: Lost Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 1993 (first published by Oxford University Press, 1978; 999 Queen W, 1868).

Susan Meurer & David Sobel: Working at Inglis: The Life & Death of a Canadian Factory, James Lorimer & Co, 1994.

Carolyn Strange: Toronto's Girl Problem: The Perils & Pleasures of the City, 1880 - 1930, University of Toronto Press, 1995 (Mercer Reformatory "fallen women").

Irit Shimrat: Call Me Crazy: Stories from the Mad Movement, Press Gang Publishers, 1997.

Ian Robert Dowbiggin: "Keeping This Young Country Sane: C. L. Clarke, Eugenics, & Canadian Psychiatry," in his Keeping America Sane: Psychiatry & Eugenics in the United States & Canada, 1880 - 1940, Cornell University Press, 1997 (C K Clarke).

Steven Maynard: "On the Case of the Case: The Emergence of the Homosexual as a Case History in Early Twentieth- Century Ontario," in On the Case: Explorations in Social History, Franca Iacovetta & Wendy Mitcheson (eds), University of Toronto Press, 1998.

Jacalyn Duffin: A History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction, University of Toronto Press, 1999.

Geoffrey Reaume: Remembrance of Patients Past: Patient Life at the Toronto Hospital for the Insane, 1879 - 1940, Oxford University Press, 2000.

Elm Street, Nov 2000 (Panopticon 2001).

"Canadian psychiatrist loses job after electro- shock controversy," canada.com (via walnet.org), Dec 17, 2001.

Donovan Vincent: "Giant prison may be built in Toronto," Toronto Star, Mar 7, 2002.

Tom Warner: Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada, University of Toronto Press, 2002.

Toronto Reference Library Picture Collection (Don Jail windows & solitary confinement cell; Central Prison; The Madhouse (Bedlam) from A Rake's Progress VIII (detail), William Hogarth; Joseph Workman; psyciatrist's couch & credentials).

Go on to: CULTURES

World city

Immigrant experiences & myths of diversity

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/libtrin/2pnotat.htm

March 2002 / Last revised: October 19, 2003

Rick Bébout © 2002-2003 / rick@rbebout.com

|