QUEEN STREET

Downtown

Streets of faith

Church & Bond:

sizzling preachers, divine

& democratic

|

Toronto the Very Good

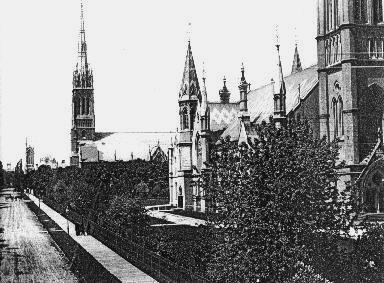

Contending spires, 1854. Palace St (later Front) out front, with notable structures numbered. Left is St Lawrence Hall; 6-15 (less 12) are churches: St James' Anglican Cathedral, Zion Congregational, St Andrew's Presbyterian, United Presbyterian, St George's Anglican, Knox Presbyterian, Holy Trinity Anglican, the Catholic St Michael's Cathedral, &, not in this view, Unitarians, Primitive Methodists, African Methodists, & African Baptists. |

Toronto was long called "The City of Churches." Aerial views of the 19th century show a landscape mostly of small low structures, punctuated all over by spires. In the 1854 view at the left, 33 key landmarks were numbered, nine of them churches. Ten others were wharves; the artist knew what mattered to the burghers of Toronto the Good.

These 1854 spires rise in close proximity, most not far from the corner of Yonge and Queen. Not visible here: the Primitive Methodist on Bay, Unitarian on Jarvis, the African Methodist Episcopal on Richmond or the African Baptist near Queen and Victoria, all there by then.

Many attending those African churches had arrived on the Underground Railroad, joining black people already here. Upper Canada had banned trade in slaves -- but not existing slavery -- in 1793; those brought in bondage by American Loyalists had remained so, their next generation emancipated at age 25, the third at birth. A city directory of 1846 listed 93 "coloured" men in Toronto; in 1850, 70 men and six women.

We don't know about children, or know figures beyond those years: race was not recorded before (perhaps a sign that prejudice was growing as more black people arrived); nor in later directories (likely influenced by the local Anti-Slavery Society, formed in 1851). Nor do we know these are full figures: escaped slaves had good reason to keep their names off the record.

These spires stood not simply as testaments of faith but thorns of fraction, faiths ever rent by contending theologies. Those burghers took The Word (or its varied interpretations) as Law, the Good often not good enough for the Very Good.

There were not just Methodists but Primitive, Episcopal, New Connexion, Bible Christian, Methodists. St Andrew's Presbyterian on Adelaide at Church was "Auld Kirk" Church of Scotland; Knox on Richmond (the Bay once Simpson's now there, the church long and maybe still owning the land) was Free Presbyterian. The United Secessionists ("an ecclesiastical paradox," as one historian noted) had their own presbytery over on Bay.

Protestants could unite on one thing: their mistrust of Catholics. Civic politics were long dominated by Orangemen, out on "The Glorious Twelfth" of July to mark the Battle of the Boyne, King Billy (William III, of Orange) bashing Irish Papists in 1690 -- if, centuries later, more wary of French ones in Canada. Orange parades often turned riots; they're now relics. Still, Toronto's "Official Centennial Book" of 1934 could say: "those evil weeds are not common to-day, even though Toronto is resolutely Protestant and strongly Orange."

No more. Some of the spires shown above (or their later descendants) still stand, together, on parallel streets just east of Yonge: Church and Bond.

|

The church of Church St

The first St James' in its 1807 clearing; the forth in a view not to be had until the Market Square condominiums cleared the way in 1982, leaving open this vista. Below: the dead cleared for condos -- or nearly. Notice north of St James', marked in protest to note how many were due for disinterment: 3,000. The project was cancelled in Nov 2001. |

Church Street is named for this town's first church, at the corner of King since 1807: St James' (or, as some have it, St James's). This small temple of wood set in woods, oriented east-west and later painted blue, was Church of England but not state established -- if certainly home to the establishment of the day. They paid good money for pews: one gent got his at auction for 35 pounds, his heirs holding it for two pounds rent per a year.

Until 1812 St James' was York's only church: "dissenting" Protestants, even the town's few Catholics, sometimes worshipped there. Its rectory was home to the Home District School, the "Blue School," direct ancestor of what is now, further north, Jarvis Collegiate Institute.

Enlarged in 1818, in 1833 rebuilt in stone, reoriented with its sanctuary set north (though thought by some "the least ecclesiastical of all points of the compass"), St James' became Cathedral of the Anglican Diocese when its "presiding genius" Archdeacon John Strachan was ordained Bishop of Toronto in 1839.

On January 6 of that year his cathedral burned; by December 22 it was rebuilt. Ten years later it burned again -- as did everything between Church and George north of King, Toronto's first City Hall south of it too, where St Lawrence Hall now stands -- in the Great Fire of 1849.

St James' would rise again -- if not without real estate wranglings: some congregants wanted to sell off the King Street frontage to commercial developers, turning their new church to face Adelaide. Backed by civic protest (not all of it Anglican) others kept it facing King -- in fact shifted off the old foundations to the centre of the block, perhaps, it was later said, "as a cunning scheme to prevent the sale of land at all points of the compass."

More than 150 years later St James' would try to sell off land to the north, for a towering condo -- 3,000 souls beneath a parking lot there to be rudely disinterred. Public protest stopped the project.

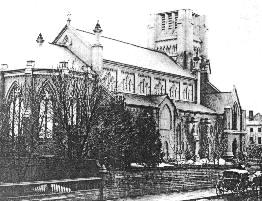

The fourth (and current) St James' was up by 1853. If not done: architect Frederic Cumberland promised for 10,000 pounds (half from insurance, the rest from pew rent) a "usable" but not complete cathedral. Its porches, tower, spire, and finials were added by another architect, Henry Langley, in 1874. For two decades the stolid yellow brick bulk of St James' was, as Eric Arthur wrote, "a shorn lamb."

Since then St James' has soared: its cross 306 feet over the street long marked the highest point in the city. Its clock, an 1875 gift from the City, still rings the hours (quarter hours too), if with a less sonorous bong than Old City Hall. It recently got a new peal of bells, tuned to scale; on late afternoons we can hear them ringing the changes all across downtown.

Inside, beneath the hammerbeam ceiling and marbled chancel, Bishop Strachan lies in his tomb, undisturbed since 1867. That is, unless he's somehow got wind of what goes on up the street, famous now not for churches but gay congregations at Church and Wellesley.

|

"Shorn lamb"

St James' as it was for 20 years, before Langley's pinnacles & spire. Fred Cumberland still gets prime credit, not only as the city's most famed architect of the mid 19th century (University College also to his credit) but as Muscular Victorian Man of Influence -- later director of a railway, a bank, & commander of his own regiment. |

|

Cathedral (not)

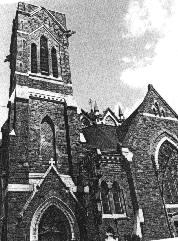

Metropolitan United; below in Langley's "High Victorian" Gothic, as it was when opened as the Wesleyan Methodist Church in 1872. |

|

Taller (if less "high")

Burned in 1928, Metropolitan's body was rebuilt, mostly on the same walls if taller, its airy pinnacles gone to heavier "Collegiate" Gothic favoured by then. Bottom: playground beneath its cliffs. |

Methodism had a bad rep in Old York. Its founder John Wesley (who died in 1793, the year York was founded) had been English, if renegade from the Church of England; many local adherents were American born, served by roving "saddle bag preachers." The Anglican establishment ("having the distaste of all 18th century gentlemen for 'enthusiasm' of any sort") suspected them agents of republicanism.

Most Methodists took the proper side in the War of 1812. With their clergy granted status they had by 1818 a small frame chapel at King and Jordan (where the 1929 Bank of Commerce now stands). Outgrowing it by 1833, they built another at the corner of Toronto and Adelaide streets -- from whence a year later 40 members decamped over differences of doctrine to another frame chapel, on George.

In time the flock regrouped, by 1844 building at Richmond and Victoria a church soon called "the Cathedral of Methodism" -- a creed without cathedrals, if by 1885 under a common Methodist roof. That church does not survive; its successor does, set back from Queen between Bond and Church on a plot of green long called, for its original owner, McGill Square.

Designed by Henry Langley, opened in 1872, Metropolitan Wesleyan Methodist Church was even more worthy of the word "cathedral." Methodists had by then won commercial power and social respect; they flaunted it, setting their grand church between true cathedrals: St James' Anglican down Church Street and St Michael's Catholic up Bond.

Further up Bond at Crookshank (now Dundas) Street, another church had stood since 1863, home to Congregationalists renegade from Zion. They'd left in 1849, zealous opponents of slavery, Zion not; for a while they had wandering through makeshift sites. Their 1863 church, big if plain, was replaced in 1879 by one more fine -- if no cathedral: sects descended of Puritans built "meeting houses" without nave or sanctuary, to Anglican eyes mere auditoriums.

But Bond Street Congregational was grand, detailed in "Free Gothic," and huge: its octagonal, lantern topped hall could seat 2,000 -- in rapt attention to some sizzling preaching indeed.

|

Lost Tribe come home

Bond Street Congregational, home to defectors of Zion, where popular pastor Dr Joseph Wild prophesied "the end of the Satanic era and the reconstitution of the world by the Ten Lost Tribes, whom he identified with the British people."

Bond Street would hear fiery sermons well after Wild's: it became the fundamentalist Evangel Temple. In the early 1970s it burned -- literally. Despite efforts to restore the building, designed by E J Lennox, who also gave us Old City Hall, it was torn down: this shot is from Bill Dendy's Lost Toronto.

|

|

| Bond Street, late 19th century: "Toronto exactly as it wished to be seen," William Dendy wrote in Lost Toronto: "The City of Churches." Here Metropolitan, St Michael's, Bond Street Congregational; beyond it, far left, the tower of the Normal School. On the west side, now filled by St Michael's Hospital, was the Greek Revival Bond Street Baptist. |

In the 1880s Methodists, Congregationalists and Presbyterians had begun talking about uniting as a "national" church. Some hoped to include Catholics; others to give Canadian Protestants a counterweight to the hefty Church of Rome. Baptists and Anglicans were invited too; in time they and some Presbyterians stood aside.

The rest, in a 1925 council held at Metropolitan, founded The United Church of Canada. Fired by the "social gospel," also spawning Canada's social democratic parties, it became known for liberal activism. And, as the banner across its porch at the top of this page shows, an occasional bit of that Old Time zeal.

|

Bond Street's Catholic enclave

William Thomas's 1845 St Michael's Cathedral (if its tower & dormers not his), seen past "quite incompatible ecclesiastical buildings" to its north. Below, entrance to the Bond St wing of St Michael's Hospital, the archangel himself watching over all inside too. |

Begun in April 1845, St Michael's is Toronto's oldest surviving cathedral -- if not the first Catholic one. When Michael Power was named first Bishop of Toronto in 1841, he chose as his seat what was then the only Catholic church in town: St Paul's, built 1823-26 well east on Queen. Its 1887 successor stands there still, on Corktown's Power Street.

Bishop Power chose the site for St Michael's, laid its cornerstone, but did not live to see it opened: he died tending his Corktown flock during the typhus epidemic of 1847. Consecrated in September 1848, the cathedral and its rectory to the north, "The Bishop's Palace," begun at the same time facing Church Street, became the focus of a Catholic enclave downtown.

The cathedral was designed by William Thomas -- but for its later spire by Henry Langley (ever busy) and "quirky dormers stapled onto the broad roof" by Joseph Connolly in 1890. Thomas also did the palace, if not its north wing or later third floor. In 1852 that wing saw the birth of St Michael's College, fledged in 1856 if settling under the wing of Basilian Fathers up on the Park Lot of John Elmsley Jr (son of the Anglican chief justice, converted to Catholicism "by a pamphlet on transubstantiation written by the Bishop of Strasbourg" -- and not incidentally by marriage). There it remains, part of the University of Toronto.

Across from the cathedral in 1892, the vacant Bond Street Baptist Church was turned by the Sisters of St Joseph into a lodging for women, soon a hospital with 26 beds, six doctors, five nurses, and the first Catholic nursing school. In 1910 St Michael's Hospital -- like many others -- became a teaching institution affiliated with the University of Toronto.

Adding wing upon wing, the latest five new floors atop an existing 11, it now fills the entire block north of Queen to Shuter, between Victoria and Bond streets. Still owned if not run by the Sisters, it's long had a reputation for cardiology and, with the forced annexation of Wellesley Hospital and not without controversy, a big HIV practice. (In its halls once, asking for directions, I got from a Christian Brother: "This way, my son." I was amused, and otherwise well treated.)

North of the cathedral stand "quite incompatible ecclesiastical buildings," as Eric Arthur called them: church offices, the ground floor long housing the Catholic Information Centre. North again is St Michael's School, built in 1900 -- now the Choir School if still with entrances marked "Boys" and "Girls" (if the latter covered; and I never see any girls).

A parking lot at Dundas and Bond, north of its playground, was once site of the Loretto Convent. On Church just up from the palace is the Society of St Vincent de Paul, a major Catholic charity.

So: Cathedral, Palace, College, Hospital, School, Parish Hall; all in the name of St Michael, "Toronto's Urban Angel" as the hospital says. And so he can seem, even to an old gay liberationist. I live near the top of Bond, making it my regular stroll down to Queen; I always enjoy it -- if for more radical inspirations too.

|

|

| Bishops & boys: The Archbishop still resides on Church (officially at least); on Bond: musical lads in black dress pants & burgundy shirts, even on the playground. |

|

Jewish to Greek; Lutherans across the street

Hagios Georgios, born 1895 as Holy Blossom Temple. Below: "perky" Germanic abstraction. |

There were very few Jews in the Town of York, few more in its first years as the City of Toronto. Among early arrivals, in 1842, were the Rossins, by 1857 opening a big hotel (200 rooms and five floors; famous panoramas were shot from its roof), and the Nordheimers, who went famously into pianos.

Most Jews in Toronto at the time had arrived from Central and Western Europe, often via the United States. The city's modern Jewish community descends mostly from Eastern Europe and the Russian Pale, coming in the great exodus of 1880 to 1914. But even in 1856 there was community sufficient for two congregations.

One already had a cemetery; the other, with a scroll of the Torah borrowed from a synagogue in Montreal, began meeting in September over Coombe's drug store at Richmond and Yonge, as the Toronto Hebrew Congregation (Sons of Israel).

Adding Holy Blossom to their name in 1869, they had a synagogue on Richmond by 1875. Twenty years later they moved to "a Byzantine domed" cube given "a Romanesque facade" by architect J Wilson Siddall (who also gave us the South St Lawrence Market in 1904), at 115 Bond Street.

Adopting Reform ritual in 1920, Holy Blossom was, as the City's centennial book said in 1934, the "only Reform congregation in Toronto; forty others follow the orthodox ritual" -- most west, soon north, following community moves. By 1938 Holy Blossom would move, to Bathurst north of St Clair. It remains the biggest if not sole Reform synagogue, others Orthodox, Conservative, and Hasidic.

Its house still stands on Bond, if with domes less Byzantine, as the Greek Orthodox Church of Hagios Giorgios -- mother church of a community also now to the north, along Danforth Avenue. The tympanum got its mosaic St George and his Dragon by 1984; in the shot here they (well, Giorgios anyway) watch over a wedding.

Germans, once Toronto's biggest ethnic group (that is, not English or French) are rarely noted in this town's modern multicultural mosaic. Some, led by William Moll Berczy (later known as a painter) helped hack Yonge Street through the bush, founding the town of Markham. But they more famously settled the West, far and near: Kitchener, Ontario, until World War One was called Berlin.

Still, a "perky abstraction" -- solid if not quite Luther's feste Burg -- at 116 Bond since 1898 (the style then called "Modern Gothic") marks their determination as a 1998 plaque says, "to have their own church and to use German as the language of service to the Glory of God."

Born St John's Lutheran, later German Lutheran, now First Evangelical Lutheran, this structure replaces an earlier wooden meeting house, built by a congregation first formed in 1851. It has lately been decked with a banner celebrating a century and a half of German worship on Bond Street -- for more than 40 years with Jewish neighbours, Holy Blossom Temple right across the way.

A federal plaque out front marks the career of Theodore August Heintzman (1817 - 1899), German immigrant to the US in 1850, if doing better in Canada after 1860: his name, like Nordheimer's, has since meant fine pianos.

|

Secular sizzlers

William Lyon Mackenzie's post-Rebellion retreat; Egerton (at) Ryerson: resolute Methodist founder of resolutely non-religious public schools. |

Religion and politics were ever tangled in this town, sermons often of secular import. At 82 Bond Street we find the final home of the city's most famed preacher -- if never a man of the cloth.

William Lyon Mackenzie -- radical publisher, thorn in the flank of the ruling Tory Family Compact (Anglican; his church United Secessionist), mayor of Toronto at its inception in 1834 -- is best known as firebrand of the 1837 Rebellion. A failed one, ending with his flight to the US. Pardoned in 1849 he returned and was reelected to the legislature, there until 1858.

Mackenzie did not win his battle, but his Reform allies under Robert Baldwin and Louis Hippolyte LaFontaine (English Protestant and French Catholic, working together) did in time win the war -- securing government responsible to that local legislature not, through Compact flunkies, to the Colonial Office in Westminster.

This house is not a Rebellion site but a gift, bought for Mackenzie by friends; he lived here only from 1858 to his death in 1861. But in its back garden stands a monument to the Rebellion: built at Niagara as the Pioneer Memorial Arch, opened in 1938 by William Lyon Mackenzie King (his grandson, then prime minister); dismantled in 1967; parts gathered here two decades later.

|

|

|

Firebrand:

William Lyon Mackenzie: Mayor, 1834; Rebel, 1837. Here late in life, if still looking ready for a fight. Top left: his house at 82 Bond, from a Toronto Historical Board postcard. Right: Garden monument at Mackenzie House, inscribed:

"To the memory of the men and women in this land throughout their generations who braved the wilderness, maintained the settlements, performed the common tasks without praise or glory and were the pioneers of political freedom and a system of responsible government which became the cornerstone of the British Commonwealth of Nations." |

At the top of Bond Street stands Egerton Ryerson, his works at both its ends. In 1870 he laid the cornerstone of Metropolitan; well before that he was, as his plinth says, "Founder of the School System of Ontario."

As much a Methodist as John Strachan was Anglican, he fought off the Bishop's bids to keep education under church control. Chief Superintendent of Schools for Canada West from 1847, he gave the province a public system, Catholic "separate" schools still supported but the rest free of denominational control -- as they were not elsewhere: Quebec schools were long either Catholic or Protestant.

Behind him (if not in view) stands Fred Cumberland's 1852 Normal and Model Schools, first teachers' college in the province. Or rather its façade, now leading down to a vast Recreation and Athletics Centre two floors beneath the green of what was once St James Square -- now surrounded by Ryerson, Egerton's legacy.

Born 1948 as the Ryerson Institute of Technology, by 1964 a Polytechnic Institute, it is now Ryerson University. Its motto: "Wisdom. Applied." A sentiment, still, rich with Methodism -- if Egerton's Ryerson is, of course, a proudly public institution.

|

Faith's final resort

Buy / Sell / Trade -- & hope for the best. |

Back down Bond, looking across Metropolitan's green, we see what seem unlikely neighbours: pawn shops. More than a dozen fill the east side of Church Street, all the way from Queen to Shuter, with a few more as far as Dundas. There are no brass balls if lots of brassy signs: Buy, Sell, Trade.

Businesses of like mind often congregate: many older cities have a Bread Street; Boston has Fruit and Milk. York Street, when The Ward was in messy flower, was known for pawn shops, flaunting those classic balls at Osgoode benchers up the way. Why we have them here in the shadow of church towers, no one I've asked is able to say. The most prominent, McTamney's, born on Yonge in 1860, moved here in the 1930s -- whether to anchor hawking or join it, I don't know.

But I'm likely not alone in enjoying this juxtaposition, perhaps one not so odd: some denizens of these streets of faith, a few sleeping under their spires, have little more than faith to live on.

See more on:

The Park Lots, in A line on a map (1793).

Church & Wellesley, in Promiscuous Affections: Citizenship: In the city & on the street.

The Rebellion of 1837 (& '38), in Losers -- Who sometimes win, in Promiscuous Affections.

Sources (& images) for this page: Jesse Edgar Middleton: Toronto's 100 Years: The Official Centennial Book, City of Toronto, 1934. Eric Arthur: Toronto: No Mean City, University of Toronto Press, 1964 (St James' shorn). G P deT Glazebrook: The Story of Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1971 (1854 spires). Stephen Speisman: The Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937, McClelland & Stewart, 1979. William Dendy: Lost Toronto, 2nd edition, McClelland & Stewart, 1993 (Metropolitan & Bond St, 19th C). Frederick H Armstrong: A City in the Making: Progress, Peoples and Perils in Victorian Toronto, Dundurn Press, 1988. Douglas Richardson: A Not Unsightly Building: University College and Its History, Mosaic Press, 1990. And historical plaques -- federal, provincial, municipal, & ecclesiastical -- on Church & Bond.

Go on to:

Dreams of grandeur

University Avenue: From bucolic boulevard to monster monoliths

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/downtown/2pfaith.htm

June 2001 / Last revised: November 13, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 /

rick@rbebout.com