QUEEN STREET

Moss Park, Trefann, Corktown

Government's house

& housing the governed

Parliament Street: Regent Park,

Cabbagetown (old & "Old")

& St James Town

|

Lone reminder

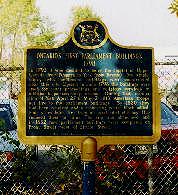

Plaque just off Berkeley St, south of Front: "Ontario's First Parliament Buildings 1798," illustrated below in John Ross Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto -- the land marked in 2001 by Budget Truck Rental.

|

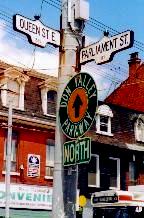

At the corner above in the early 1980s, in a walk-up flat over a store, lived a friend named Dan. A student of Russian history, he was better known at the time as Sister Appassionata della Bawdy House, Order of Perpetual Indulgence -- gay men doing street theatre agit-prop in drag as nuns. Dan's place was their convent. There, he was fond of saying, they presided over the site of Canada's true (and not entirely secular) constitutional foundations: Queen and Parliament.

The Queen doesn't live in the neighbourhood (though not a few queens still do), nor is Parliament there. But the street now bearing its name did once reach it. Or nearly: this stretch was born as Mill Road leading north, often called the Road to Castle Frank, Governor Simcoe's log pillared cabin overlooking the Don. The original Parliament Street, further south, is now the bottom stretch of Berkeley.

It was there, on the lakeshore just east of the Town of York, that Simcoe planned as he said in 1796 "such Buildings as may be necessary for the future meeting of the Legislature." Simcoe left town before they were begun. At the end of 1797 his successor Peter Russell wrote him in England with news on the project.

- "The Two wings of the Government House are raised with Brick & completely covered in. ... I have not yet given direction for proceeding with the remainder of your Excellency's plan for the Government House, being alarmed at the magnitude of the expense...."

That remainder, a vice-regal residence due to cost 10,000 pounds, never rose. The intended route to it from town was nonetheless named Palace Street (part of what is now Front). The single storey wings, 24 by 40 feet, were connected in 1805 as Simcoe had proposed "by something like a Colonade" of wood.

This modest complex did not stand long, burned by invading Americans in 1813 -- if later avenged, perhaps too grandly, by the British burning Washington. Rebuilt by 1820 it burned again four years later, ignited not by hothead invaders but an overheated chimney flue. The Legislature decamped to the York Hospital, in 1829 to new parliament buildings on Front Street between Simcoe and John -- and from there in 1893 to the pink palace at Queen's Park.

So, Ontario's parliament has long left Parliament. Walk south on the street and you'll see only one sign of it: a plaque just east of Berkeley, set against a chain link fence on the south side of that historic site's current tenant -- a Budget Truck Rental lot. Its excavation did allow an archeological dig, history paid at least passing attention before it was paved over.

|

Angled wings;

compass points One of Moss Park's three set back winged towers. Below, Regent Park South: a tower facing due east over Park Public School on Shuter St (renamed in Nov 2001 for Nelson Mandela, there on a visit); & a view from Regent Park North.

|

|

Regent Park North:

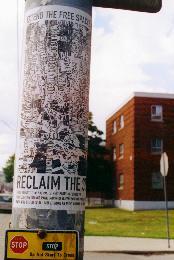

Farewell to Oak Street And most streets, Oak now "Not a through street." Few are, familiar routes dead-ended or closed. What's your address? 229 Sumach -- or so it says below. Try finding 260 Sumach: it fronts a different courtyard. Bottom: "Reclaim the Streets!" Dundas here, the street fest advertised set to begin a mile west. Taking Dundas Dolce Africana, just west of Parliament.

|

North of Queen, just up Parliament on the west side, is another historical plaque. If one you have to look for: it's not at eye level but at one's feet, imbedded in the sidewalk.

- "Rupert Hotel Fire: On December 23rd 1989 a fire roared through the Rupert House Hotel, a licensed rooming house on this site. Despite the heroic efforts of firefighters and several tenants, ten people died in the blaze, making it one of the worst fires in the history of Toronto. The tragedy sparked action by municipal organizations to improve the conditions in rooming houses throughout Toronto. This plaque was dedicated by the City of Toronto and the Rupert Coalition in a special ceremony on May 18, 1993 in memory of the ten who died."

Their names follow: nine men and one woman. A 1913 photo of this corner (you can see it on another tour, linked to below) notes in its caption "the newly named and quite respectable Rupert Hotel." It clearly fell on hard times, as did much of its neighbourhood, rooming houses licensed and otherwise long common here.

"Municipal action to improve their condition" was less common -- though more sweeping efforts to "improve" the area go back decades. In fact Parliament offers a potted history, from the 1930s to the 1960s, of governments' efforts to house the people they governed.

And of master planners' shifting visions of ideal accommodation: their dreams of urban blight swept clean, replaced by "garden cities" and local villes radieuses -- dreams rarely shared the people who lived in them.

Just a few steps north of that Rupert Hotel plaque, the streetscape of small stores falls away -- opening north to Shuter, west behind a spiked black fence, a parking lot and grass, to one of Moss Park's 16 storey towers, set at an odd angle well back from both streets.

Look east along Shuter's north side, past the '50s Modern Regent Park / Duke of York Public School, and you'll see five other towers: each 14 storeys, also angled in ignorance of the streets. Their long sides were designed to face the exact points of the compass -- twisting them off downtown's grid: its "north" is actually some 12 degrees northwest. Cartesian logic prevailed, yet again, over local conditions.

They are part of Regent Park South, a bit older than Moss Park if looking more modern, designed by Toronto's master of '50s Modernism, Peter Dickinson. His interiors there were innovative: two storey apartments with internal stairs, units interlocking across the building, one floor facing north, one south (or one east, one west), allowing cross ventilation and requiring corridors only on every other floor. The design won Canada's top architectural award for 1958 (though tenants griped they could fall down the stairs without even leaving their apartments).

Regent Park South also got more varied structures, townhouse rows as well as Dickinson's towers. But few faced streets: within the perimeter of Parliament, Dundas, River and Shuter, all through streets but one disappeared. Some ended in cul de sacs, a favourite of suburban "garden city" planners -- among them this site's designer, working for a federal bureaucracy, CMHC: the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

But when it comes to blockbusting (not to mention sheer banality), Regent Park South had already been outdone by its parent project just up across Dundas Street.

|

|

From complex urban community...

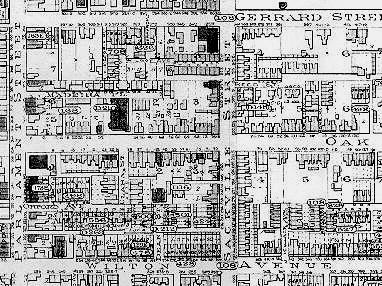

The neighbourhood northeast of Parliament St & Wilton Ave (now Dundas St), in 1903. |

Planning mavens obsessed with "blight" had long cast an eagle eye on the blocks east of Parliament Street south of Gerrard: "the largest Anglo Saxon slum in North America" it was said -- ripe for "renewal."

Plans in a report of 1932 called for an approach that would become widespread: Kick everybody out and tear it all down. Start again with a blank slate -- cleared even of history. That report set the tone: "...as we evacuate those factories and hovels, we must raze them and bury the distressing memory of them in fine central parks and recreation centres."

And the scope: it recommended sweeping away every neighbourhood south of College and Carlton, from Dovercourt to the Don. It was not simply renewal, but a massive experiment in social engineering. And, if not so sweepingly, it went ahead -- that old Anglo slum selected as the prime Petri dish. Plans of 1932, 1943 and 1946 by different firms all called for complete clearance, closing of streets, and construction of apartment blocks set in various artful arrangements on a vast sea of green laced by pedestrian pathways.

But they were just plans: there was no money, no authority -- until 1946, when the newly formed CMHC supplied backing (for "expansion of employment in the post- war period") and the Ontario Planning Act gave local governments the power to unleash their planners. In 1947 the voters of Toronto agreed to let the City spend $5,900,000 on "a low cost or moderate cost rental housing project, with possible government assistance... known as Regent Park North."

Where the name came from is unclear. There was a Regent Street in the area -- the only street that would fully survive within Regent Park South. But as John Sewell has written: "in all probability it is derived from John Nash's 1812 plan for London, Regent's Park, where large elegant mansions were place in a park- like setting. The irony could hardly be more clear."

The final plan marched mean brick blocks of three and six storeys (cross shaped, a Corbusien fetish) across the site's 26 acres, leaving space only for "fine central parks and recreation centres." Or one centre, safely hidden from main streets.

|

...to urban planners' blank slate:

The same blocks in J E Hoare's 1947 plan for Regent Park North -- pretty much what got built. |

|

Regent Park, North and South -- in fact the whole area from Parliament to the Don south of Gerrard down to Queen Street -- did once have a well known local name. If one it lost.

-

"This was his neighbourhood, dotted with the homes of his neighbours and friends. The street names greeted him with long-known familiarity -- Sackville, Taylor, Parliament, Oak, Sumach, Sydenham.... A few houses on almost every street were as verminous and tumbledown as any in the city, but next door or across the street was the same type of house, clean and in good repair, reflecting the decency and pride of its occupants. ... This was a neighbourhood almost without tenements, and the streets were lined with single family houses, many of whose upper stories [sic] accommodated a second family."

-- Hugh Garner, Cabbagetown

Garner's novel was set during the Depression, when "Cabbagetown" meant slum. It was published in 1968, by when as he notes in his preface some applied the name to the area north of Gerrard -- "but this is an error." Even an affront to the "decency and pride" of the original Cabbagetown.

-

"Contrary to uninformed and malicious public opinion at the time, there were no substantial instances of rehabilitated slum-dwellers storing their coal in their new unaccustomed-to bathtubs....

"The new housing was a godsend to ex-Cabbagetowners, a relief to the police force and a welcome change to the district firefighters. The social agencies now had fewer calls, and the charities fewer local recipients. The new generations of Cabbagetowners had money and jobs, which most of those who came before them had not."

"Nobody should get eulogistic over a slum," Garner wrote in that preface of 1968 -- when urban renewal still had some cachet. And Regent Park's tenants had been pleased as first: in Farewell to Oak Street, a National Film Board documentary made at the time, many were glad for escape from gouging landlords and grotty digs to new apartments with rent geared to income.

But they had lost those single family houses, lost upstairs neighbours they were bound to know; lost not just houses verminous and tumbledown but those clean and in good repair, left with buildings that someone else, not they, were supposed to take care of.

They lost front doors, stoops, windows looking directly onto the street. Eugene Faludi, planning Thorncrest Village in 1946, had made all living room windows face south; he was irked when residents didn't like it. They wanted to see their street-- sensing proprietorship, even responsibly, for the world outside their doors. In Regent Park they lost that, lost even the streets themselves. They got instead those "fine" parks running right to their doors. Common land became no man's land, under the purview of no one in particular.

|

Police, firefighters, social agencies, politics

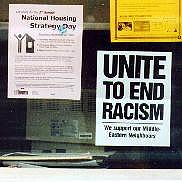

51 Division, on Regent St. Below, just north on Dundas, Firehall Number 7 & the new Regent Park Community Health Centre; posters in a Centre window, postdating Sept 11, 2001: "We support our Middle Eastern Neighbours."

|

|

Download fink-out

News on Parliament, August 2001.

|

But for the police -- hardy relieved. Neither were firefighters, social agencies, or charities. Nearly half the residents of Regent Park North came to depend on some form of social assistance. Firehall Number 7 on Dundas at Regent Street is among the busiest in the country. Just down Regent, 51 Division regularly plays backdrop to TV news crime stories, the suspects portrayed usually black.

Most people there are not: three quarters count as members of visible minorities; of them a quarter are black, more than 60 percent Asian, some Latin American. It is clearly no longer "Anglo Saxon." But to most people who never go there, it is still a slum (if, they might be surprised to see, a rather tidy one). Images once called up by the word Cabbagetown -- poverty, low life, crime, drugs -- now rise in the public mind on hearing "Regent Park."

The people of Regent Park resent the slur, if living with its periodic reality -- and resisting it. Many of the area's social services were begun by those people, most notably the Regent Park Community Health Centre. Founded in 1973 after five years of planning to address a total lack of family doctors or dental care in the area, it took nearly ten years more to win consistent government funding. In 1997 it got $6.3 million for a new building, opened in 1999. There's a plaque near the door:

- "Dedicated to the people of Regent Park, past, present and future. Their strength, courage and vision built this home of community health and spirit."

On a recent visit I found banners in the lobby reading "Welcome" in 14 languages; regular services are offered in English, Cantonese, Mandarin, Vietnamese, Somali, and Spanish. I also found information on other local services -- and on police "stop and search" powers, and a new (and more restrictive) immigration bill.

People working there, some as volunteers, believe as their Mission says "that the most effective way to improve health is to have programs designed and run by the community affected," and that "social, economic and political issues, such as poverty, inadequate housing, and unequal access to services, affect health."

That has a familiar ring to an old AIDS activist, offering hope for Regent Park and its peoples' future -- a future that will increasingly depend on their own strength, courage and vision. The governments whose master planners stuck them with this neighbourhood have given up on "the vision thing," but for an eye to the bottom line.

In 1998, when Ontario's Tories forced the amalgamation of Metro Toronto's six municipalities into a single "megacity," they downloaded lots of responsibilities -- promising "zero impact" on the civic budget: in exchange they took the cost (and control) of education off local hands. The City was left holding the bag for, among other things, public transit, social welfare -- and housing.

The feds had fled the housing field in 1993, the CMHC no longer a player. The Ontario Housing Corporation had been scrapped by the Tories after their election in 1995. The Metropolitan Toronto Housing Authority was gone by 1998 (along with Metro). The new City was stuck with their existing sites, as well as its own downtown Toronto CityHome projects, begun in 1974.

Most CityHome sites, relatively new (if often renewing old buildings), were small scale and in good repair. Many of the CMHC's, OHC's, and MTHA's were huge, old, and a mess -- among them Regent Park. Handed housing stock needing lots of work, the City begged for repair funds. The provincial government said no.

Their mantra is tax cuts -- meant to "boost the economy" and "lift all boats." Lately it seems they've gone too far, a sagging economy likely to leave them in deficit. Faced with public needs they'll say: Sorry, the cupboard is bare. Robbed bare -- in the name of privatized efficiency.

|

Worlds apart

If not obviously: Gerrard St, looking east from Parliament. Below, parkette triangle where Gerrard divides -- & worlds collide.

|

|

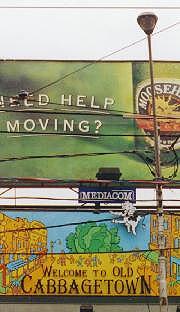

New "Old Cabbagetown"

Self-conscious signage starts at Gerrard, still mixed upscale & down; north of the big Welcome billboard facing west down Carlton -- more up.

|

Gerrard Street is a social divide. It's not glaringly obvious on the ground: an urban route much like any other, if the sidewalks on its north flank more lively then the serried rows of Regent Park set back on its south. But, as Edward Relph said in The Toronto Guide, his 1990 tour for urban geographers, "the areas north and south of Gerrard Street are social worlds apart."

The street separates Census Tract 31(entirely Regent Park North) from Tract 68, running north between Parliament and the Don to Winchester. Beyond, to Bloor, is Tract 67. Those northern tracts cover what is now called Cabbagetown -- its contrasts with old Cabbagetown to the south graphically clear.

|

Cabbagetown is not wildly rich: income levels in its southern tract are just above the metropolitan average. North of Bloor in Rosedale they approach $200,000; in the suburban Bridle Path nearly half that again. But it is a community comfortably well off -- next door to one that, notoriously, is not.

These neighbourhoods did not always so differ. The south was settled from the 1840s by Irish immigrants who, legend has it, grew cabbages in their front yards; the north developed later, its classes more mixed. From the late 1870s, as Patricia McHugh wrote: "Workers' cottages were built side by side with more generous double houses for the middle class." But most nearby jobs in the mills, brickyards, breweries and abattoirs along the Don were far from white collar.

The area declined, designated for the same "urban renewal" seen to its south. But vocal citizens spared it demolition -- just long enough to tap late '60s disdain for suburban flight. Many young professionals, arts and media types among them (a CBC Radio studio long on Parliament is now home to the Danny Grossman and Canadian Children's dance companies), wanted to live downtown.

They could find houses here for as little as $10,000 -- if needing work. But even left alone their value rose, along with the area's cachet. By 2001, according to the Toronto Life Real Estate Guide, the average selling price here was $400,000.

These divergent worlds collide -- along with others -- where Gerrard divides: a stretch meeting Parliament from the west; a jog south crossing it. Set between them is a small parkette with a concrete pool and, for a time, big benches. They've been replaced by individual seats, less conducive to snoozing: the park also draws the homeless, some from shelters farther west.

Worlds mingle (less in collision if sometimes warily) all the way up Parliament. On its east side just north of Gerrard we get donuts, Dollar Bargains, Buck or Two, the big Bargain Shop; tucked between The New Aristocrat restaurant, clearly less upscale than an eatery once in the nabe: The Peasants' Larder -- where, as poet Gwen Hauser once put it, "dinner cost a King's Ransom."

People down here crowd No Frills for "lower food prices everyday," warehouse style; those further north find essentials more elegantly displayed, at Essentials Gourmet and Fine Food Shoppe, maybe stopping at Lettieri for an espresso.

Across the way a Victorian row has been split levelled, a bistro below named for cartoonist Ben Wicks (ever wry, if now late); above is a druggist with a postal wicket, and a Sears catalogue store. Fine cheeses flank takeout pizza. Odd bits of hardware can be had from a hole in the wall near Gerrard, or at Home facing down Carlton, more tastefully ramshackle than that franchise's suburban usual.

It is a street chock-a-block with contrasts, main street to divergent communities; a stretch in parts self conscious to the point of twee, in others too tired, or poor, to bother. I like Parliament Street. I'm there often, to find deals at No Frills or see friends who don't have to -- but who just might anyway.

People in the original Cabbagetown likely didn't post signs declaring its identity. As Edward Relph has written: "They knew where they lived. The new residents feel differently. The name and history of the area, with associations of hardship, became interesting, worth declaring." The streets, shops and homes of new Old Cabbagetown, he says, "wear their new oldness as self- consciously as models in a fashion show."

Toronto is dotted with neighbourhoods morphing from taciturn working class understatement to showily signified identity. "Old Cabbagetown" went up over turf at first called simply, if vaguely, "on the Don." City planners later tagged its northern reaches Don Vale. As late as 1985 Patricia McHugh's tour of the area in Toronto Architecture: A City Guide still called it "Don Vale" east of Parliament, its west side "Old Cabbagetown" -- the quotation marks her own: each tag, she said, was a misnomer.

No matter: Don Vale faded, Cabbagetown prevailed -- by the late '70s flying its own flag. The green cabbage was planted by the Ward 7 Business Association, among its key players realtor Darryl Kent. Openly gay, he helped fill the nabe not just with "double income no kids" Yuppies, but their same-sex variant: Guppies -- "A-Gay" gentrifiers famed as both heroes of urban preservation and villains forcing out less tasteful neighbours.

In the early '80s Parliament Street looked set to become Toronto's "gay village." It lost out to Church (for reasons I deal with elsewhere), a strip gone so screamingly self conscious it feels more Gay Disneyland than urban community.

Relph called Cabbagetown's adopted name and newly old style "Peasant Chic." More recent critics might lay a charge of "cultural appropriation." But the area's avid self- identification isn't just a matter of anxious upscale trendiness. Among the designers of its cabbage flag was Betty Dawson, then president of the Ward 7 Business Association (if bothered by "Business"; it became "Professional"). She has lived in Cabbagetown all her life.

Both Cabbagetowns: Betty Dawson grew up on Oak Street. Her neighbourhood is not likely to be torn down, again, any time soon.

|

Of cabbages & DINKs

Modern Cabbagetown was preserved by poverty: in a stable if rundown area, few pay houses much attention beyond minor repairs. It was renewed mostly by DINKs -- Double Income No Kids: professional couples (if a few with kids). Gentrification was gradual and isn't yet total: the Winchester St duplex above is renovated on the right (its entrance around the side); on the left a sign offers furnished rooms for rent.

Edward Relph notes gentrifiers "privatizing" houses, turning the focus inward, away from the street -- often by tearing off porches once sheltering "old car seats or benches where people would sit drinking beer, talking with neighbours, watching the kids who had the run of the front yards."

Many front yards are fenced, some elaborately planted (if not with cabbages). Porches do remain (if with no car seats), their fine woodwork now more an ornament to horticulture than to street culture. |

|

In St James Town's shadow

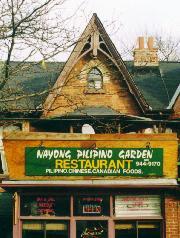

Filipino, Tamil, Bengali, Punjabi. Towers seen up Parliament, & marching west along Wellesley.

|

Farther up Parliament the scene shifts again, if just subtly in streetscape. Past an Esso station once done up on Darryl Kent's lead in Victorian brickwork (since torn down and more meanly replaced), past the Menagerie Pet Shop (on Parliament for ages), we see Filipino eateries, East and West Indian groceries, signs in scripts more familiar in Colombo, Dhaka, Madras.

Glancing up we can't miss their reason for being: tall white towers looming north and west, St James Town -- the biggest high rise housing project in Canada. Not a public project, a private development begun in the mid '60s, intended Edward Relph writes as "a city within a city" for young professionals working downtown.

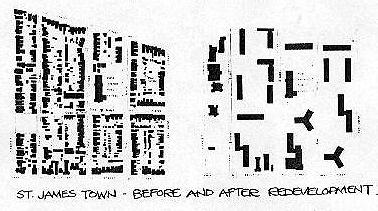

Like most Corbusien dream cities of its time, it has no city streets. They're gone -- along with their houses, "two- and three- storey homes built in the 1870s," John Sewell says, "for the upper middle class" -- replaced by tall towers, the tallest 33 storeys, set at random in vast expanses of green. Or grey.

Super blockbuster: The neighbourhood northwest of Parliament & Wellesley, before & after the mid-1960s. From Edward Relph's The Toronto Guide, 1990.

St James Town's developers, a consortium of private corporations, could count on civic support. Land assembly for their syndicate was handled by W W Gardiner Real Estate -- run by the son of Metro chairman Fred "Big Daddy" Gardiner. By 1956 they held half the lots north of Wellesley from Sherbourne to Parliament. The City resisted pressure to expropriate the rest on their behalf, fearing accusations of civic power abused.

But local pols had shown their hand in 1953, zoning the entire city east of Yonge to the Don, from Queen north to Bloor, for high density development -- then meaning high rise. In time there was no need for blatant exercise of public power. Private power (cast as "inevitable market forces") would more than suffice, the planned decay of "blockbusting" coaxing reluctant residents to sell.

What was, & what is

|

The art of blockbusting

In The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning, John Sewell detailed corporate tactics deployed on once stable neighbourhoods, making "redevelopment seem inevitable."

"A developer would purchase a property, then leave it to a middleman to run in the short term. The middleman would lease to the most downtrodden of tenants, usually roomers whose lives had fallen apart. Houses would quickly become unkempt: repairs would not be made, walks would not be shovelled in winter, garbage accumulated on porches and lawns. ...

"Several such houses on any one block could significantly alter the character of the neighbourhood. Nearby owners not only had to put up with these changes -- middlemen and developers disclaimed responsibility, while city officials said they were powerless to intervene -- but found that fire insurance companies refused to renew contracts. ...

"At this point owners decided it was time to move. Since likely purchasers did not find the area attractive, the only offer they could expect would be from the developer who had caused the problems in the first place."

|

St James Town began as a decent address, even a trendy one -- if, as often assumed, gay people set trends. I knew a few living there in the early '70s, living myself just south by 1973, its last redbrick towers soon ranked along Sherbourne, blocking my fifth floor view to green Rosedale.

But the original towers east of Bleecker (the only remaining through street) were already getting rundown, their vast, barely peopled setting soon the inevitable no man's land of urban crime (or self fulfilling fear of it). It became, as Edward Relph says, "an immigrant reception area." Some 20 percent of its population is Filipino; more are South Asian, many Tamil; there are Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans. About a fifth are black, many of them Somalis.

St James Town is home to nearly the same percentage of visible minorities as Regent Park North, if slightly better off -- and many more in absolute numbers. Its neighbour just southeast of Parliament and Wellesley, northern Cabbagetown, is much better off and mostly white. But the biggest contrast is in sheer numbers.

In Cabbagetown's Census Tract 67, some 1,700 people live on a third of a square kilometre (half the tract; the rest, St James' Cemetery, houses many more dead). St James Town's Tract 65, just one quarter the size, houses more than 15,000. Its population density -- more than 73,000 souls per square kilometre -- is the highest anywhere in Canada.

Cities thrive on density -- long seen by planners as a social evil. But it has its limits: people stacked to the skies on land otherwise vacant don't find civic life on the street. They rarely even find streets. Their public realm is vast, unbounded, maybe dangerous. It's not really theirs at all.

The "city within a city" that became not a city at all nearly consumed the city around it. Had development marched on in step with 1953 zoning, all of east downtown would have become St James Town -- beginning directly south: blocks all the way down to Carlton were bought up and torn down in the early 1970s, pending future high rise renewal.

But "South of St James Town" was not to be more of the same. It became instead a battle cry. Its few remaining houses, some new ones built to the old scale, and its apartment co-operatives mark land where master planners came face to face with vocal, well organized citizens. They had urban visions of their own.

See more on:

The Rupert Hotel, when "quite respectable," in a 1913 shot of public lavatories at Queen & Parliament, in Urban amenities; erotic anxieties.

The original imposition of Cartesian logic on the local landscape, in A line on a map.

Others taking control of community health, in Promiscuous Affections -- the grassroots birth of the AIDS Committee of Toronto in 1983; its education efforts in 1989 & its best work, promoting local smarts over mainstream media panic, in Sex: Policing desire, playing politics, pushing pills.

For Parliament's bid to become "gay downtown," see Promiscuous Affections, 1980. Church & Wellesley as a gay theme park is in Citizenship: In the city & on the streets; look for "Rainbow Country!"

Sources (& images) for this page: John Ross Robertson: Landmarks of Toronto, "Published from the Toronto Evening Telegram," 1894 (1st parliament buildings). Charles Edward Goad: Atlas of the City of Toronto & Suburbs, Goad's Atlas Plan Company (Regent Park area, 1903). Hugh Garner: Cabbagetown, Ryerson Press, 1968. Patricia McHugh: Toronto Architecture: A City Guide, McClelland & Stewart, 1989. Edward Relph: The Toronto Guide: The City; Metro; The Region, prepared for the Annual Conference of the Assoication of American Geographers, Toronto, April 1990 (with thanks to Max Allen; St James Town illustration). John Sewell (foreword by Jane Jacobs): The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning, University of Toronto Press, 1993 (Regent Park North, 1947). Betty Dawson (by phone, Nov 2001). Toronto Life Real Estate Guide, Feb 2002.

Go on to:

Master builders meet citizen activists

Trefann Court & beyond: from "urban renewal" to true civic life

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/mtc/2pparl.htm

November 2001 / Last revised: November 1, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com