|

View

from on high

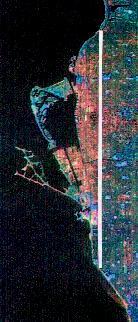

Downtown Toronto from 900 km in space -- west here, not north, at the top. South (ie, left): the Leslie Street Spit branching out into Lake Ontario; the Toronto Islands sheltering the harbour.

Overlaid (as it was on the land) is Queen Street's long straight line, 16 km from Roncesvalles in the west to Fallingbrook in the east |

QUEEN STREET

Plotting history

A line on a map

On the road with the Royal Engineers:

Logic confronts landscape -- & wins

City streets have varied origins. Some began as a path on the ground, carved by wheel or foot sensitive to the contours of landscape: its rises and falls; the meander of sinuous streams. But many more, in many cities, began as a line on a map.

Quite often, a straight line.

"Nature," it has been said, "abhors a straight line." The makers of the modern world avidly adored them. In The Reinvention of the World: English Writing 1650-1750, my friend Douglas Chambers, whose works in print and on the ground ever mix land and literature, noted that the word "map" long meant "a picture of a local place" -- less a plan than a description, even a celebration, of what Alexander Pope called "the genius of the place." It was a not a view from on high, but from within.

In the century of René Descartes this art of intimate "chorography" began to give way, Douglas wrote, "to what we now mean by geography, a science ruled by Mercator's projections." By mathematical precision, abstract Cartesian "logic." And the Cartesian grid: The British Army's Royal Engineers would lay it down all over the Empire.

Governor Simcoe's Queen's Rangers likely knew first not the land they would grid, but its precise location on a globe: 43 degrees, 39 minutes North; 72 and 23 West (or five hours and 17 minutes behind Greenwich). Their sole concession to immutable geography was to set their grid more or less in line with the lake shore, skewing our local sense of north off True North by some 12 degrees west. Not that anyone but cartographers or astonomers need notice.

Their lines otherwise ignored local topography, the logic of paper's two dimensions soon faced with the genius of land's three. No matter: where native tribes had sensibly trod the crest of a rise once the shoreline of ancient Lake Iroquois (giving us Davenport Road), the engineers' lines charged straight up it.

Meeting streams they swept over them, in time buried them in sewers. Only the valleys of the Don on the east and the Humber far west were too wide, some of their tributary ravines too deep, to fill in. They would, if much later, be bridged.

Of all the straight lines those engineers drew, among the first and longest was the one we now call Queen Street. It was not always a street, not always called Queen. But that line on a map has been there since this town's very first days.

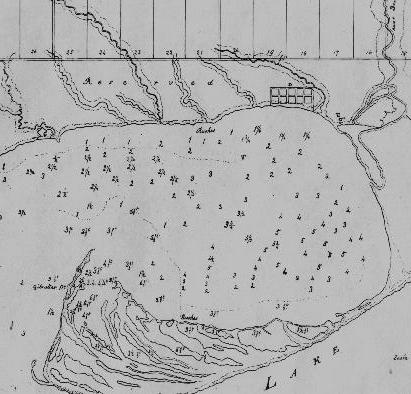

1793

Plan of York Harbour

Surveyed by

Alexander Aitkin

"by order of Lt. Gov. Simcoe"

Simcoe ordered Aitkin's survey as he was planning to set the new capital of Upper Canada on this site -- he hoped temporarily, favouring a spot now London, Ontario. The first capital, Newark, now Niagara on the Lake, had sat within range of American cannon.

What matters most here is defence: the harbour dotted with depth markings; the long peninsula sheltering it (not an island until 1858 when a storm cut a gap in its eastern arm); and the garrison that would defend its west entrance. It's at the left, marked G, at the mouth of what came to be called Garrison Creek. Across the gap is Gibraltar Point, also with guns. Further west this map shows (if not in the part shown above) sites for a blockhouse, barracks, and battery.

Tucked against the harbour's northeast shore is a grid of ten small blocks: the intended Town of York, as it was proclaimed -- over what this land's first people had long called the area, "toronto" -- on August 27, 1793. Its limits were set at George Street (west), Berkeley (east), Duke (now Adelaide) and Palace (now Front Street). Far right is the Don River, the only waterway seen flowing into harbour here to flow visibly still. Its deep valley and "malarial" mouth would long block the town's spread to the east.

The straight line running east and west marks the route of Queen Street. But in 1793 it's not a street, just a line: the first concession, base for future concession lines to the north paralleling it at intervals of 100 chains (a surveyor's 66 foot chain; so 6,600 feet, 1.25 miles, or a bit over two kilometres). Those lines now run as major streets: Bloor, St Clair, Eglinton, Lawrence, and beyond.

Most land south of that first line is marked "Reserved," for the garrison. What's north is also reserved -- for the gentry: Park Lots (numbered east to west; the numbers shown here would change) running up to what is now Bloor Street, each 10 chains wide, 100 acres in area "to be granted," Edith Firth wrote in her 1962 history The Town of York, 1793-1815, "as 'douceurs' to the officials as compensation for having to come to York."

Which is to say, bribes: to coax them from the relative comfort of Newark to the barely settled wilds of Muddy York. Simcoe intended they become Upper Canada's landed gentry. Most instead became real estate speculators, selling their prospective country seats for later urban development.

But the Park Lots' footprint remains on Toronto. As late as the early 20th century city atlases showed their numbered bounds; they are marked in streets named for their owners (Jarvis; Denison; McGill), in green bits once their estates (Grange Park, Moss Park), even in bequests by their later generations.

Stand on any such jog (like the swing north where Carlton links to College at Yonge) and you likely stand on a boundary between Park Lots: their owners were not alway mutually cooperative. I happen to live on one where they were: Jarvises to the east, McGills to the west, a lane they shared now Mutual Street.

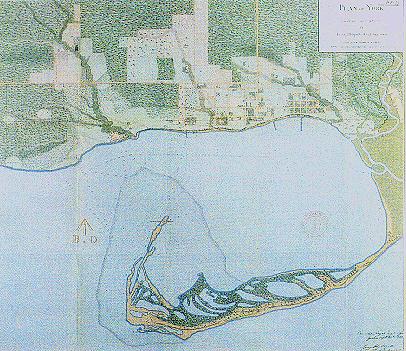

1818

Plan of York

"Surveyed and drawn

by Lieut. Phillpotts,

Royal Engineer"

George Phillpotts gives us here (gloriously) the harbour again, littleYork still hugging its northeast shore. If getting bigger: settlement jumped from what came to be called "Old Town" to "New Town," west of Yonge Street. Low marshy land between -- Taddle Creek then running there, Jarvis and Church streets now -- was reserved for church (St James', there by 1807), market (opened in 1803 and still selling), school, hospital, gaol, pillory, and stocks.

At the top, centre right, the line of Yonge Street (named for Sir George Yonge, British Secretary of State for War, if on his pen and ink rendering of this map, Phillpotts spelled it Young) cuts up through dense forest. Begun in January 1794 as a military road from the 4th concession (now Eglinton Avenue) north to the Holland River, it was later run south to Bloor Street (well off this map).

Simcoe, following the Romans, named all his martial routes "streets" -- though they began as mere trails. Most of the line on this map was called the Road to Yonge Street, leading from the edge of town up to Bloor, and a toll gate. Only later did it run down to the bay. The wider clearing at the centre lies west of what is now University Avenue.

But the route of note here for our purposes is the one striking way west from Yonge -- if just a short block east. In 1797, when York sheltered all of 241 souls, it became the town's new northern limit. South of it (where the woods first thicken) was the west limit, at Peter Street; beyond remained the Garrison Reserve.

On early maps this route is often marked "Dundas Street" -- not to be confused with what is now Dundas downtown. That began as many different streets (among them Arthur, Agnes, St Patrick, Crookshank, Wilton, and Beech) not linked up and renamed until the early 20th century.

The original Dundas was another military route (honouring Home Secretary Sir Henry Dundas), also planned in 1794 if, competing for attention with Yonge, not opened until 1799. Heading north from what is now Queen and Ossington, it turned west to parallel the lakeshore (if safely inland) all the way to Burlington Bay.

Locally, this stretch got called the Road to Dundas Street. Or, more often, Lot Street -- for those Park Lots it fronted. At least over to Peter: beyond, its name kept changing. An 1837 map of the Garrison Reserve shows it as Egremont (with another toll booth). But it was also called Lake Shore Road: running from Lot Street, at Peter, along the lake west to the Humber. Laid out in 1805, it sometimes got tagged for towns it led to beyond: Burlington Road; or Niagara Road.

Far west in Parkdale it often got called, again, Lot Street. It was sometime still before it was Queen; even then not all of it.

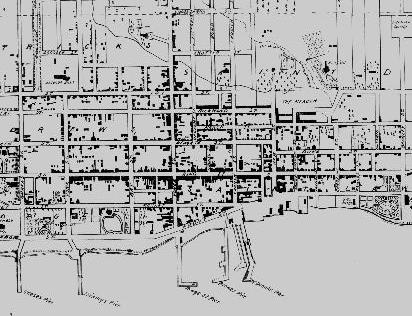

1842

Toronto in the

"Surveyed, Drawn & Published by James Cane, Toph. Eng.; Dedicated by special permission to His Excellency the Rt. Hon. Sir Charles Bagot, G.C.B., Gov'r Gen'l of British N. America"

Province of Canada

Topographical Plan

of the City and Liberties

In 1834 the Town of York, population not quite 10,000, became the City of Toronto -- reclaiming its ancient name against a tag then too common: "Little York." It was the first city in Upper Canada, which in 1841 would become Canada West, united with Canada East (the former Lower Canada, now Quebec) as British North America's single Province of Canada. Hence the title and dedication here.

Toronto's city limits were set west at Bathurst; north at the line of Crookshank (shown in dashes near the top of this map), and east at the Don River -- but for a strip taking in the lakeshore well past Ashbridge's Bay, if only south of what is now Queen.

Beyond the limits were the "liberties," as Glazebrook's The Story of Toronto tells us "an old English word meaning territory within the jurisdiction of a city rather than a county" which once sufficiently peopled could be swallowed up with no fuss. By 1852 liberties west to Dufferin and north to Bloor were encompassed by the City. Other annexations (among them, in 1887, the one we call The Annex) came later.

So, our line on the map is no longer out of town, if still not heavily settled. The streets most visibly built up here are King and, if not far north, Yonge. But Osgoode Hall has taken its place next to College Avenue (as University then was) north of Lot Street. Soon it will not be Lot. In 1844 to honour Victoria, then just seven years on the throne, the street was rechristened Queen.

Or parts of it. East of the Don it was for some years Kingston Road -- still there a block past Coxwell, where it curves off to the north. Along the line further east a map of 1880 shows a road allowance, a short stretch later made a real street -- if then called Maple Avenue -- north of Balmy Beach in the Village of East Toronto. (Its main street is still called Main Street, the only one in Toronto if nowhere near downtown).

By 1884 the entire street on that first concession line is at last called Queen. Riverdale, east of the Don to Greenwood Avenue, was annexed by the City that year; in 1887 lots just north of Queen as far as East Toronto. The old village itself was consumed in 1908, the next year Midway (between it and Riverdale) and a strip east to Victoria Park. That was the City's final eastern limit -- at least until 1998, when Megacity swallowed Scarborough (and much more) beyond.

Even downtown, Queen took time to become a continuous street. In 1842, as you can see above, Lot Street is broken by "The Meadow" at Park Lots 5 and 6 south of William Allan's manse Moss Park, here tagged Mossfield, in fact his birthplace in Scotland. The real name would later apply to digs less grand.

A map of 1878 shows that gap at Moss Park filled in, a street called Queen running east to the Don; by 1884 it ran well beyond. To the west, as a local commentator noted that same year:

- "There is a continuous line of houses and stores from the centre of Toronto, at the corner of Queen and Yonge Streets, along Queen to the main street of Parkdale ... furnished with stores and hotels on a scale equal to that of the best streets in the city."

That scale remains (mostly, if now rarely seen as "the best"), that line still continuous: Alexander Aitkin's line, first set down on a map in 1793. A line beyond town becoming roads out of town, often named for towns on the way; now a vibrant city street named Queen, very much part of Toronto.

Go on to:

Of time & the river

The Don: salmon to sludge to concrete; in time, to life revived

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/2pline.htm

December 2001 / Last revised: November 13, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com