QUEEN STREET

Downtown

Halls of law

& governance

Osgoode Hall; City Halls current,

former, & long gone

Eye opener

|

Cities are much more than buildings. Architecture has often been seen (too often by architects) as an abstract art form: concepts standing free of contexts economic, social, political -- in short, human. Buildings are but one thread in the fabric of place -- if a vital one, along with the land: the warp, we might say. It is life, weaving through them, that woofs.

But if architecture is, as has been said, "frozen music," it is also concrete history. Regard for buildings brings questions. Why is this here? Why does it look the way it does? Who built it? When? What did it mean to them? What does it say about the culture of its time? Think cathedrals. Or skyscrapers. Or an Iroquois longhouse.

We identify cities with their buildings: Notre Dame; the Empire State; even the CN Tower. But a city's history seen as the history of its buildings tends to the grand and official, written mostly by a class at home with officialdom, good taste, learned erudition. It is hardly accidental that among Toronto's most celebrated structures is University College, or that the halls we'll see here have got lots of ink.

Nonetheless, the appreciation of civic architecture can lead to deeper regard for the broader urban fabric.

- "The architectural history of Toronto has been in the mind of the writer since the time, many years ago, when he first made it a habit of wandering with no fixed objective through the streets of the old town. ... I have suggested that we in Toronto are curiously apathetic towards our history in terms of landmarks, street names and the like; indeed surely no city in the world with a background of three hundred years does so little to make that background known."

-- Eric Arthur: Toronto: No Mean City, 1964

Born in New Zealand in 1898, Eric Arthur came to Canada at age 25 via England and his education there, as an architect. In 1932 he helped found the Architectural Conservancy of Ontario -- a place known for conservatism if rarely conservancy, especially in this town. His 1964 book, full of buildings labelled "demolished," might well have been called, as William Dendy's later work was, Lost Toronto.

But Eric Arthur was out to show Toronto as No Mean City -- a title suggesting its citizens suspected it mean: a Victorian jumble of mediocrity, much of it deserving demolition. Most did. His work helped change their minds.

My interest in this city's history was born of its buildings: I grew up an aspiring architect. One place in particular, quite grand (see "Dreams of grandeur"), occupied me for most of a year. I was 22 at the time, in town not quite three years.

It was then, in 1972, that I first read Toronto: No Mean City. I have read much of it many times since -- coming, as you can see, to a mild critique of its "landmark" approach (one going back to John Ross Robertson's 1890s Landmarks of Toronto and Henry Scadding's 1873 Toronto of Old). And, as you'll also see, to immense gratitude. So, herewith, some attention to architecture and architects. If very much in contexts economic, social, political, and human.

|

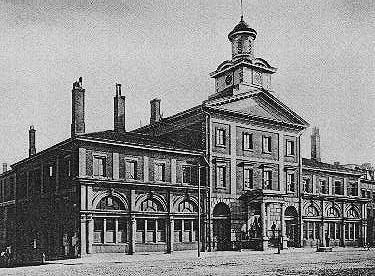

Spreading law

Even out of town. Osgoode's east wing, all there was (if even this) in 1829, set at the top of York St above Lot (later Queen) -- then the city's northern limit. Below: An 1857 view, up York from atop the Rossin House Hotel, shows additions built in 1844, the west wing a twin of the east. Renovation begun just after this shot was taken would lose the little dome & give us the imposing portal to the centre block, shown further below. |

Historians of architecture love Osgoode Hall. It's not just grand: it's a great detective story. Who designed it? That is not, as Eric Arthur wrote, a "story where all possible villains are known to the reader, and only a hint from the author is necessary for him to make up his mind."

Its architects were long thought to be the Montreal firm of Hopkins, Lawford and Nelson, J W Hopkins's signature on a lovely watercolour elevation of 1844. More than a century later, a professor at McGill University uncovered Hopkins's date of birth: 1825. "That he was four years old in 1829," when Osgoode Hall was begun, Arthur writes, "and nineteen in 1844, would seem to put him out of the running for building in both those years."

An engraving of the time, quite similar, was signed by one H B Lane. Henry Bower (or Boyer) Lane seemed a more likely candidate: in 1843 he had designed Little Trinity Church (we'll see it in Corktown). But he'd got to town only in 1840. So who did 1829?

That first block, now the east wing, may not have been born the Regency confection we know: Robertson in his Landmarks called it "a plain square matter of fact brick building two and a half stories in height." Its Ionic portico may have been added, along with the centre block and west wing, in 1844.

As for its original architect, well.... Dr William Warren Baldwn of Spadina seems to have had a hand in; he often did. "Even so, our most likely contender," Arthur says, "is John Ewart." We hear little more of Ewart, "a shadowy figure," of his (and Baldwin's) erstwhile partner James Chewett, a bit more.

But: "One other character swaggers across the Osgoode stage" -- John Howard, Toronto's most famed architect of the day. He is best remembered as a benefactor: his Colbourne Lodge still stands in High Park, the 165 acre estate he donated to the city. Most of his works, the biggest the 1846 Asylum, rank among the demolished.

What a coup if one could prove his connection with this Palladian palace of law! Alas, a diary entry of 1843, "Laid out the grounds in front of Osgoode Hall," is at best circumstantial evidence.

Firm evidence connects Osgoode Hall with Frederic Cumberland and his partner William Storm, putting it in league with University College, St James' Cathedral, and a host of works (some others still standing) by these two, widely regarded as the greatest architects of 19th century Toronto.

"Few," Arthur says, "were more competent," the 1857 Caen stone façade of the centre block and that elegant wrought iron fence (if replaced at least once since) surely their work: "We have ample documentary proof." What a relief: architects worthy of Osgoode found at last.

|

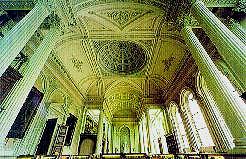

Legal splendour

Cumberland's 1857 Great Library, behind the windows of the centre block.

Versailles?

|

|

Earlier tales of Osgoode Hall are nearly as much fun -- to students of real estate. The turf in question is one of those prime plots of speculation set out north of the Town of York: the Park Lots. In this case, Lot 11.

John Elmsley, who owned the top halves of Lots 9 and 10 (east of what is now Queen's Park), later bought 11 just west. His widow sold half of it, 50 acres for 184 pounds, to merchant Alexander Wood (remembered in Alexander and Wood streets -- and, for a scandal of 1810, by gay people now living near them). Three years later Wood sold half that to Attorney General John Beverley Robinson -- for 1,000 pounds.

The Law Society had, since 1820, been looking for land to house its hall. They'd had their eye on Russell Square at King and Simcoe, land granted to Peter Russell by Simcoe's successor: Peter Russell. But by 1829 it had gone to Upper Canada College (since gone to Avenue Road north of St Clair). Robinson offered his legal fellows six of his acres -- for the same price he'd paid for all 25. His net profit (well placed to make it): 126 pounds per acre.

The benchers' cost per acre was 45 times what Wood had paid Widow Elmsley. But they could afford it -- even if their budget, set in 1820 for land and building both, was "not to exceed 500 pounds." They'd come up with 2,000 among themselves, and in 1825 got the government (which they ran) to give them a "grant in aid."

What those half dozen acres may now be worth as prime downtown real estate, only barristers (or their solicitors) can say. One does not imagine they're about to.

Like Upper Canada's legislators before them, the Law Society first set up shop just outside town. From 1797 to 1834, the route flanking the Park Lots' south limit -- then Lot Street, now Queen -- was also the Town of York's northern limit. Within five years of their arrival the new City of Toronto surrounded their site, its limit set 400 yards north at what is now Dundas Street.

Why law and governance chose what were then the burbs, I don't know. Tradition may have been in play: London's great Inns of Court were born in fields northwest of the old City's square mile; Parliament's Palace of Westminter stands even farther afield. The object in part may have been to avoid (symbolically, if never in fact) distasteful association with trade.

Or, like Louis XIV out at Versailles, to get some distance on the mob. Osgoode's famed "cow gates" -- each an iron cage within which one must squeeze around a diagonal barrier -- date at the latest from 1857; even before that, it has been noted, there were few neighbouring cows for barrister to bar. Likely more fresh in memory was the Rebellion of 1837. The rabble is able to pass though those gates -- but only one rouser at a time.

Best I know, the site was never mobbed. Not that security is ever perfect: some years ago an attorney was shot dead during trial in an Osgoode Hall court room. One imagines the benchers have tightened up since.

|

Town market

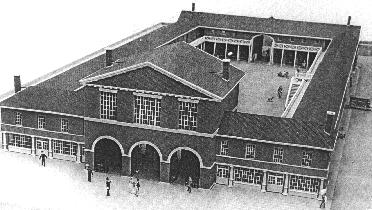

York's markets circa 1820 & 1831, as illustrated in Robertson's Landmarks; the third on the same site, here in 1873 still very much a market, later renovated to grandeur as St Lawrence Hall. |

Toronto's seat of civic government has been on Queen West just over a century. In the century before it sat east, and south -- if not quite so far southeast as the original Town of York.

The town had no town hall per se, barely even civic governance. It was run by justices of the peace, magistrates appointed by the lieutenant governor (he a royal appointee), who met as the Court of General Quarter Sessions for the Peace of the District of York -- that district much more vast than the town.

Peter Russell, not governor but administrator, found this rather too general, drafting a "police bill" for "regulation, discipline and control" of the town. Never enacted ("police" seen as foreign to British tradition, "bobbies" yet to come), it does seem fit for the man local historian Bruce Bell calls "Tyrant Russell."

York did have a market -- if not quite in York. In October 1803 Peter Hunter, second lieutenant governor, decreed "a public market to be held on Saturday in each and every week during the year ... for the purpose of exposing for sale cattle, sheep, poultry, and other provisions, goods and merchandise."

The site chosen, just west of town south of King at New (now Jarvis) Street, had no market building until after 1820, "wooden shambles" torn down in 1831 for a more substantial ramble of brick. The building is barely known but for a "political meeting" in 1834 at which, Robertson reports: "While one of the speakers was haranguing the assemblage part of the balcony gave way precipitating people to the floor below." And for most of it burning down in the Great Fire of 1849.

There have been (as you can see) quandaries over that lost structure's look. And its architects: Eric Arthur attributed it to W W Baldwin and J G Chewett; a later source says "James Cooper, following a competition." But all agree that the place served, from March 1834, as the first City Hall, York having then become Toronto.

|

| The Town of York's Market, Toronto's first City Hall. Model made by students at Ryerson University's architecture school (apparently on evidence later than Robertson's drawing of 1894, above left), since on display at Toronto's fourth City Hall. |

The site of that first City Hall, if not the hall itself, remains well known -- for another hall. Just a year after the Great Fire, St Lawrence Hall rose at King and Jarvis, still a market below if above a grand ballroom. In time shabby, covered with signs, it was nearly lost too. Renovated as a Centennial Project, its chief advisor Eric Arthur, the hall reopened in December 1967, for some years as home to the National Ballet of Canada.

Behind it had risen in red brick Victoriana another market wing, since replaced in modern buff, called the Farmers' Market. They still arrive every Saturday at 5 am, with stock fresh if, these days, rarely live.

|

Market wrapper

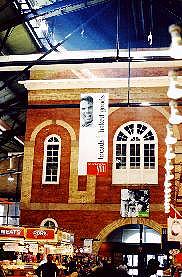

Façade of the second City Hall, engulfed by the South St Lawrence Market of 1904. Below, seen from inside, the original south face -- the best one, aimed toward the lake. |

Toronto's city fathers soon grew tired of jostling for space with poultry, produce and their hawkers, not to mention several newspapers, a school, and the Mechanics' Institute (precursor of the city's public libraries) sharing their cramped second floor. They launched a competition for design of a new City Hall.

The winner was Henry B Lane; the site was at Jarvis facing Front Street, just down from the market -- not quite left behind: the ground floor here was a market too, Council taking the floors above, a police station with cells in the cellar.

|

| Second City Hall, 1844: "Solid & industrious" -- or "a very strange looking building"? |

Lane's work, if well regarded at Little Trinity before and Holy Trinity later, was here long seen as odd, at best "solid and industrious," befitting the town. In 1891 historian G Mercer Adam called this "a very strange looking building," suggesting even that "it was unfortunate for the reputation of the architect that he had not left the province" before it went up.

H B went back to England in 1847. Those who do not recall him (few do) may be mystified in the St Lawrence Neighbourhood by an apparently inexplicable identity crisis in asphalt, reminiscent of Avenue Road: Henry Lane Terrace.

But if a jumble along Front Street, its south face is grand -- in fact its true front, facing the lake. The most common route into town then was by water; Lane's great arched windows, City Council's chamber just behind, were meant as impressive welcome. City fathers might have waved: the lake shore, now far south past acres of fill, was then nearly at their feet.

In 1899 they would decamp to Toronto's third City Hall, on Queen West. The hall they left behind would lose its wings, pediment, clock, and pepper pot cupola, its remaining bulk swallowed by the vast South Market, wrapped around it in 1904 by architect John Wilson Siddall. For 75 years it would stay wrapped, in obscurity. Renovation of the Market in 1974 exposed its bright brickwork again to public view; the old council chamber is now the City's Market Gallery.

From there I have often looked down, not to the lake but to stalls spread beneath arching steel, "exposing for sale" meat, poultry, produce, and cheese not just on Saturday like the Farmers' Market still up across Front, but all week (except for Mondays). We can pay there in "Toronto dollars" -- bought and spent at par, merchants donating 10% of their value to a local community fund.

|

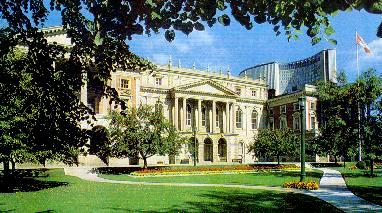

Civic neighbours

Old City Hall: seen (with flags of Olympic intent) from Queen St fronting Nathan Phillips Square; from the corner of Bay St looking northwest to its successor; & looking northeast past the Cenotaph. |

|

Last laugh?

E J Lennox:

|

Those city fathers, in 1885, had launched another competition. It would not be their last -- if, in the moment, some might have doubted the wisdom of artistic patronage meant to be more noble than the sort of cronyism they knew better.

Provincial fathers had announced one just five years before, seeking designs met to rise at Queen's Park. Three likely winners were deemed too expensive, one set to cost $612,000. But one of the judges, Arthur wrote, "had come to find favour with the government both as a person and a poker player." Richard A Waite of Buffalo, claiming he was "the only architect on this continent capable of carrying out such important work," submitted his own plan, budgetted at $700,000.

It was, of course, what got built -- if at a cost of $1,228,000. How the province's pink palace came to be so dull, Arthur says, "is, perhaps, the saddest story ever told when architects meet and the talk is of competition."

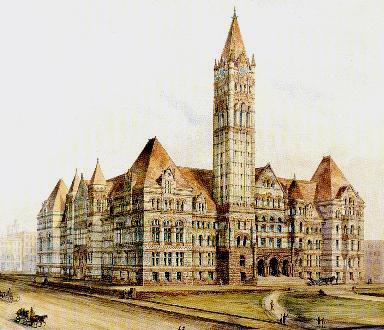

Nonetheless, competition there was for the third City Hall -- if first just as a court house, to cost no more than $200,000. Fifty designs came in; none met the budget. They tried again the next year, got 13 submissions and picked one, by an architect locally trained, his work to date mostly churches.

Edward James Lennox, born of Irish parents in 1855, would have little fun overseeing the rise of his native city's grand hall. Tenders for the foundation alone came in at $110,000. Nervous pols let its excavated pit sit idle while they waited out the next election: it froze into a skating rink, since recalled just west.

Re-elected, they asked Lennox in 1887 to give them not just a court house, but a City Hall. New plans and tenders took ages. Construction began in 1889, ground to a halt in 1891 even before the six ton cornerstone was laid, stopped again in 1892 when in a "midnight melodrama" Lennox fired the masonry contractor, stepping in to direct the work himself. Council endlessly delayed decisions, and funds. By 1895 the massive stone walls sat five storeys high with yet no roof, no tower.

On September 18, 1899, Toronto's then new City Hall opened -- still unfinished. The Mail and Empire intoned: "No more may the irate taxpayers in the bitterness of hopes deferred, cry 'How long, oh Lennox, how long?'"

| Lennox's dream, 1889: Ink & watercolour rendition by E J Lennox of his original plan (giving it, as architects often do, a more spacious setting than it would see). In the end, 10 long years later, the clock got bigger play & its tower four fierce projecting gargoyles -- later removed, perhaps lest they'd swoop down on E J's many critics. |

|

In the end it was Lennox's triumph. Built in the same material and nominal style as squatting Queen's Park -- Credit Valley sandstone piled up "Richardson Romanesque" -- City Hall soars. Lennox had learned from the master: Henry Hobson Richardson, and his 1884 Allegheny County Courthouse in Pittsburgh.

And at last he'd had some fun. A few of the faces in its intricate stonework, it's been said, caricature his critics; one genial moustachioed chap might be EJ himself. And, among the corbels under the cornice one can find some carved with letters. They read, around the entire building: "E.J. Lennox Architect A.D. 1889."

That it cost, in the end, $2,500,000 now seems a bargain -- if, on its opening day, Mayor John Shaw apparently saw some need to shush niggling critics:

- "Why people will spend large sums of money on great buildings opens up a wide field of thought. ... It has been said that, wherever a nation has a conscience and a mind, it recorded the evidence of its being in the highest products of this greatest of all arts. Where no such monuments are to be found, the mental and moral natures of the people have not been above the faculties of the beasts."

Just decades later, beasts of Mammon would prowl. Having decamped yet again, if just across Bay, city fathers sold Old City Hall to the new metropolitan government, for $4.5 million. They were immediately offered $8 million for it, by Eaton's -- who wanted to tear it down for their shiny new shopping centre.

|

Eaton's dream, circa 1966

Bay & Queen as they'd have had it in one plan (Bay sunk beneath pedestrian bridges), their plans ever changing. Later they'd offer to keep Old City Hall's tower, standing alone among flat slabs (not the slick ovoids shown here) of 69, 57 & 32 floors -- as John Sewell wrote in The Shape of the City, "like a trinket from the city's former life." Trinket to go: H B Lane's 1847 Church of the Holy Trinity. The entire block east of Bay was to be wiped clean. Local papers loved this "superblock," the Telegram gushing: "No other city would have anything to compare with the dimensions and the splendour of it." |

They found themselves up against proverbial "little old ladies in tennis shoes." Or, as John Sewell said of Friends of Old City Hall, "solid middle class professionals" who "knew all the tricks about reading reports, writing to politicians, ferretting out background information" -- not about to let the old girl fall without a fight.

Eaton's withdrew their plan in 1967 -- perhaps less wary of looking vandals than in paying the City too much for streets they meant to close. They would come back with new plans, if chastened -- as all developers would be.

The elegant 1911 Bank of Toronto had gone not five years before to the TD Centre, with no more apology than "it did not fit in" (even if TD's designer Mies van der Rohe did much admire it). Two years later, I M Pei's 58 floors of stainless steel at Commerce Court would be planned to partner, not replace, the 1929 Canadian Bank of Commerce, its 34 storeys still standing (if no longer "the tallest building in the British Empire").

Friends of Old City Hall would help spawn the Committee to Save Union Station, the push to "Stop Spadina Save Our City," and a "Reform" City Council committed to urban preservation. The powers that be learned not to mess with media savvy middle class professionals, their cherished monuments, or their comfy neighbourhoods.

This activism burst, in part, from what seems a civic paradox: "a city that had been so deeply conservative for so long," as urban geographer Edward Relph wrote in 1990, that "when old things became fashionable, Toronto had many of them left." Streetcars for instance -- if, as Eric Arthur showed, too few old buildings.

This innate conservatism would sometimes show a meaner face: "neighbourhood preservation" as cover for "not in my back yard" defence of privilege, otherwise unconcerned with the city's fate and the powers that shape it. But, further east on Queen, the bulldozer of "progress" would also be stopped by a community not much privileged, surprising even middle class professionals with lessons in how things really work. Or can.

The Battle of Old City Hall marked a sea change in Toronto's sense of itself. As did, at the same time, the arrival of one "little old lady" famously unconcerned with her attire if, with equal fame, formidable in her passion for urban life: Jane Jacobs. She would help many of us see how cities really work.

|

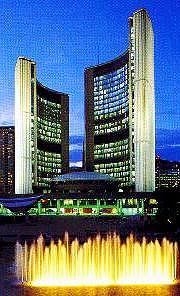

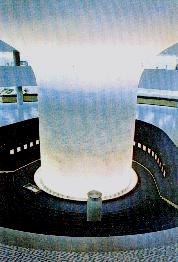

Ceremony, sanctity,

public space Top, a classic postcard shot: City Hall and its splashing pool, in the winter a skating rink. In the rotunda, the single shaft supporting City Council's saucer rests amidst regimental crests in the Hall of Memory. Nathan Phillips Square: a view south from City Hall's doors. Across Queen the Sheraton Centre on what was a honky tonk strip. The Bank of Montreal towers in white marble, the TD Centre's steel black beyond. |

Lennox's grand hall, long seen as too big, would soon prove too small. Within 15 years of its opening, Toronto would have twice the population and, by annexations, nearly twice the land it had claimed when E J's work began. City fathers sought more room. They found it just across the street.

The block north of Queen west of Bay to Osgoode Hall had been the heart of The Ward, a slum long eyed for redevelopment. Here in 1911 John Lyle had planned a vast civic square, his vision unrealized but for "one of Toronto's grandest temples of neoclassicism," Charles Cobb's 1914 Registry of Deeds and Land Titles.

In 1946 voters let the City buy the whole block. In 1951 Council said they'd build a new City Hall there, later asking a trio of local firms -- chief among them Mathers & Haldenby, known for stodgy insurance buildings -- to come up with a plan.

Their cautious, chunky slab won no fans: in 1956 voters refused to pay for it. The City launched yet another competition, this time international -- despite one local firm crabbing in the Telegram: "What would happen if the Chinese Communists ... submitted the most dramatic design?"

|

Civic evolution

New City Hall as planned in 1955, the 1914 Registry still standing to the west. In the end planners' penchant for total clearance prevailed: neoclassicism falls, Revell's clam rises. Shea's Hippodrome on Bay, famous for vaudeville, fell too; some say City Council made up for it in slapstick.

Below, opening day, September 13, 1965: a civic square filled not by regiments of trees, but 14,000 celebrating citizens.

|

Dramatic it would be, even in selection, if designed by a neutral Finn. The jury viewed 510 models from 42 countries, architects' names in sealed envelopes held by the chairman, Eric Arthur. Four jurors had selected eight likely contenders before the fifth -- and most famous -- judge got to town.

Eero Saarinen (best known for TWA's flying shells at the New York airport now JFK) said on his arrival: "Show me your discards." Among them he found a work reminiscent of his own, convincing the rest it was the best. Only later would they all learn it was the work of a fellow Finn, Viljo Revell.

Revell would hear his work called "two boomerangs over half a grapefruit" and "a couple of pieces of old broken sewer pipe." He would die, in 1964, before Frank Lloyd Wright waxed funereal: "You've got a headmarker for a grave and future generations will look at it and say: 'This marks the spot where Toronto fell.'"

Many would mark this the spot where Toronto truly bloomed. Once called "the home of righteous mediocrity," the city had raised as its symbolic heart, Bob Fulford says, "a romantic departure from the cool geometry of modernism."

New City Hall is not an efficient office building: its thin towers cup oddly arranged work space backed by their windowless shells; it is hard to heat and cool. It has never been imitated, making it unique. And, as a civic symbol, unparalleled.

Seen from the air it's an eye: in Finnish tradition, the eye of the people. Few people see those odd offices; many pass its three pairs of double doors, glowing wood set at ground level, to services circling its vast rotunda. At its centre a massive pillar holds up City Council's chamber. Many see that chamber too, designed for civic governance as theatre in the round (if occasional one ring circus).

But the real triumph is out front. The square, Fulford says, had "appeared incidental and was not much discussed," mere roof of a garage sunk below. It turned out more radically democratic than the building it fronts, "unabashedly a civic space, open to an infinity of uses ... where the people could act out their beliefs and understand themselves as citizens rather than consumers and workers."

"As an idea it was ancient," Fulford wrote. "With the creation of Nathan Phillips Square, Toronto began joining itself to that tradition." This closed, conservative town had at last moved its civic living room outdoors.

Democracy has had some rough rides in this town. From 1953 New City Hall also housed the council of the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, a regional government, its chairman, unelected but by those councillors themselves, ruling like a czar.

In 1998 Metro became, against the will of its people, the new Megacity of Toronto. The old downtown City became a relic of history, its City Hall perhaps too: Metro Hall had risen not long before at the corner of King and John, a bland office hulk called postmodern -- if owing more to Albert Speer than Frank Gehry, born in Toronto but better known in Bilbao.

Megacouncillors did have the smarts (if not right away) to move into Revell's clamshell, renovated to accommodate them. They do know symbolism (or could at least be convinced to see it as cost effective). As for what else they know, and do: well, let's just say we've still got our eye on them.

See more on:

The Park Lots, in A line on a map.

Grand plans of 1911 & my preoccupation of 1972, Union Station, in Dreams of grandeur.

The Eaton Centre, sparing Old City Hall & Holy Trinity, in Private property; public life.

Jane Jacobs, & John Sewell, in Master builders meet citizen activists.

Architects & some of their works: Frederic Cumberland's St James' Cathedral, in Streets of faith; University College (with William Storm) in Dreams of grandeur. J W Siddall's Holy Blossom Temple is also in Streets of faith, as is E J Lennox's Bond Street Congregational; the house Siddall designed for himself in 1902 appears in Promiscuous Affections, 1991 -- when my friends David Newcome & Paul Pearce had a flat there.

Sources (& images) for this page: John Ross Robertson: Landmarks of Toronto, "published from the Toronto Evening Telegram," 1894 (first & second markets). Eric Arthur: Toronto: No Mean City, University of Toronto Press, 1964. David Piper: Fodor's London, David McKay Company, 1964; revised 1971. Vincent Scully: American Architecture and Urbanism, Praeger, 1969. St Lawrence Hall, Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1969 (the Hall, & Eric Arthur). Meeting Places: Toronto's City Halls, 1834 - Present, prepared for an exhibition at the Market Gallery, Oct 26, 1985 to Feb 2, 1986 (all other images not otherwise credited). William Dendy: Lost Toronto, 2nd edition, McClelland & Stewart, 1993. John Sewell: The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles With Modern Planning, University of Toronto Press, 1993 (1955 plan for New City Hall). Toronto Reference Library Picture Collection (Osgoode Hall full façade & library; & the Hall of Memory).

Go on to:

Streets of faith

Church & Bond: sizzling preachers, divine & democratic

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/downtown/2phalls.htm

Created: December 2001 / Last revised: November 14, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com