QUEEN STREET

Downtown

Dreams of grandeur

University Avenue:

From bucolic boulevard to

monster monoliths

|

Academic avenues

An 1878 aerial view: the university grounds & tree lined roads leading to it: north from Queen (marked by Osgoode Hall, bottom left), is College Avenue -- now University; coming in west (centre right) from Yonge, also College Avenue -- at first called Yonge Street Avenue, now College Street. |

|

Gated academy

Gates at Queen (top) & Yonge, c 1868, each guarding its own College Avenue. |

|

Not heading the Avenue

And not Greek: University College (in a painting by William Storm), built 1856-59, west of Taddle Creek. |

Toronto is not know for elegant boulevards. It does have some wide streets: rural concession roads become major thoroughfares, a few blocks fronting upscale shops, most notably on Bloor Street West. But our true modern model of Baron Haussmann's grand boulevards -- smashing through the mobbed warrens of old Paris -- is surely first baron of Metro Frederick "Big Daddy" Gardiner's expressways.

Two very wide streets do meet Queen, crossing it now but at first heading just north. They came not of some civic master plan but, more or less, as gifts -- if not entirely disinterested ones. In 1813 Dr William Warren Baldwin had a boulevard laid to his estate, Spadina; later he gave it to the city, hence Spadina Avenue. For what we now call University Avenue, and College Street east of St George, we must thank college trustees.

Chiefly John Strachan, who in 1827 was granted a charter by King George IV for the founding of a college -- to be called King's (as one wag put it, "perhaps as an inducement"). Two years later its trustees bought from the Boulton, Powell, and Elmsley estates the top halves of their Park Lots, 168 acres in all, road allotments included, planning to set its campus there.

The land was far from what was then the Town of York; no road yet led there. So they set out two: one south of Elmsley land coming in west from Yonge; and one running north from Lot Street (now Queen) on a strip of Powell's. A wide strip, 120 feet: they wanted a grand promenade.

They got it: College Avenue, called by some (likely academics looking south) Queen Street Avenue, laid out in 1829, lined with chestnuts blooming pink in spring. The narrower if still leafy road east was called Yonge Street Avenue. Soon each -- at its "town" end -- had a gatehouse with keeper and signs banning "riding on the green sward," "allowing cattle or swine to run at large," "playing football," "discharging firearms" or "setting fireworks." All commercial traffic was barred. Collegial dignity must be respected.

But those avenues long led not to a college -- just to the burble of Taddle Creek. Strachan wanted King's to be an Anglican institution; Methodists and Presbyterians resisted. The "University Question" saw endless debate.

Strachan got his way (for a while): in 1842, with grand ceremony, Governor General Sir Francis Bond Head laid the cornerstone for the first building of the University of King's College. Plans called for many more -- a vast Greek Revival complex meant to terminate the long vista up College Avenue, a tall clock tower centred on its axis. But it was not to be.

The University Question was finally settled in 1849. The Reform government of Robert Baldwin and Louis Hippolyte Lafontaine voted to support only a secular institution, chartered as the University of Toronto. King's College lost its endowment, by 1853 its one building too, its land expropriated for a new provincial parliament building -- planned then but not begun until 1886.

Set on having his Anglican academy, Strachan founded Trinity College, way west on Queen. The Presbyterians had decamped to Kingston, founding what would become Queen's University; the Methodists to Cobourg and Victoria College.

The U of T's secular University College would rise not Greek Revival (or Gothic, as an alternate scheme had dressed the same layout), but in Frederic Cumberland and William Storm's massive "manly and noble" Norman Romanesque, begun in 1856 -- still seen as the city's greatest work of 19th century architecture.

Nor would it sit at the top of College Avenue but west, across Taddle Creek. It could not be seen then as it can be now, up the later if modest axial boulevard of King's College Road -- but obliquely from across the creek. To its east the lone Greek remnant of King's College soon became the "Temporary Asylum for Female Lunatics," finally torn down in 1886.

In time Strachan's Anglicans returned, other denominations too: the U of T is a federation of colleges secular and religious, Trinity, Victoria, Presbyterian Knox and Catholic St Michael's among them. Now Canada's biggest university, with satellites in suburban Scarborough and Erindale, its main campus is still in the heart of the city, on that once remote land first dedicated to higher education in 1829.

More or less: the University has grown beyond its original acreage, spreading west across St George, if losing land on the east to the legislature. But it still owns the plot of "green sward" behind that building (if leased to the City for 999 years): in 1860 it was christened Queen's Park.

|

Going gargantuan

The Armouries, 1893. Gone by 1963 to a new north wing of Osgoode Hall; recalled on a monument outside the University Avenue Court House. |

|

Edifice complex

Canada Life, its weather beacon beaming since 1931: red for rain, white for snow, green otherwise; stable when conditions are, flashing to warn of change. The tower bands ripple up or down, predicting shifts in temperature. |

With College Avenue no longer leading directly to a college, if it ever truly had, but (as you can see in the distance at the top of this page) to the massive "pink palace" of the Ontario legislature finished in 1892, it lost, as William Dendy wrote in Lost Toronto, its "pastoral and quiet" academic isolation, going more "imperial and elegantly formal."

Citizens has long strolled its length, enjoying "one of the great lungs of the city" -- otherwise bereft of parks until Allan Gardens and Queen's Park opened in 1860. No east-west street was allowed to cross College Avenue and, heeding those signs at the gates, there was no "commerce." At least not of the sort city fathers hoped for, wedded to commercial traffic and an orderly street grid to ease its flow.

In 1859, on the same 999 year lease that got it Queen's Park, the City took over College Avenue and opened it to traffic. A parallel route on its east flank perhaps already was, a civic alternative to the college's avenue opened, judging from maps, between 1842 and 1850; on one of 1858 it's called Park Lane. Below you'll find it labelled University Avenue.

So, for a while we had both. And that other College Avenue, once Yonge Street Avenue, later College Street; a short parallel stretch called Avenue Street. We begin to see how this town got -- on the same axis as University north of Bloor what, it's been said, "sounds like an identity crisis with pavement" -- Avenue Road.

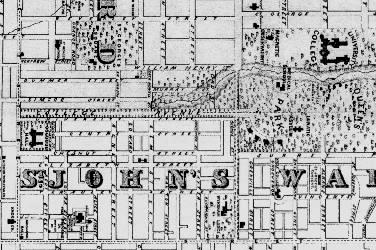

College Avenue(s): An 1873 map (north at the right) shows a College Avenue still heading off toward Yonge, with a short Avenue Street in parallel -- & the elegant College Avenue down to Queen, right beside a route once called Park Lane, here University Avenue.

Some fine houses had gone up, especially around the sylvan crossroads of College and, well, College. In time they would fall, many by 1913 for the vast complex of Toronto General Hospital, consuming to its south and east the more humble abodes of The Ward. The Hospital for Sick Children would later take more, and Mt Sinai across the avenue: homes gone to Hospital Row.

Many went in 1893 to the massive fortress of the Armouries, north of Osgoode Hall. In the same year Osgoode built a new wing, its face set to the avenue. Across the street in 1929, the Canada Life Assurance Company raised a monumental white wedding cake, its flashing weather beacon a landmark ever since.

The avenue had gone from bucolic to colossal. It would go more colossal still -- if not with the grandeur some dared dream.

|

Graphic remnant

The Graphic Arts Building, set at Richmond & Sheppard, 1913 -- in hope of Federal Avenue, planned 1911 if never to appear. |

|

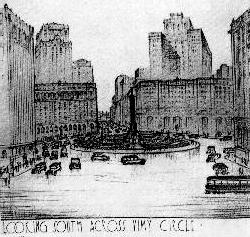

Grand terminus

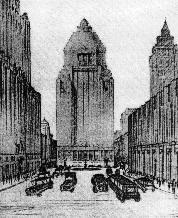

Union Station, planned from 1911, built 1915-19, opened 1927 -- meant to look up Federal Avenue. Instead, by 1929, looking right across the street to the Royal York Hotel. Below (surely to Beaux Arts chagrin): "interference" from VIA Rail, the Olympics, & hotdogs. |

The Canada Life Building, if best known for telling the weather, is in fact a relic of lost dreams. It is the only structure actually built -- of many planned -- on what was to be a downtown complex of grand Beaux Arts boulevards.

The prevailing (in fact "modern") architectural style of the decades around the turn of the century, Beaux Arts was named for its practitioners' alma mater: l'École des Beaux Arts in Paris. Its hallmarks: balance, symmetry, and proportions based on Greek and Roman models; pediments, columns, and capitals true to classical "orders"; ornament often elaborate; and monumental scale.

And the "City Beautiful": axial boulevards, grand vistas, vast plazas; les places of Paris, Regent Street and Picadilly Circus in London. In a burst of Edwardian optimism and (as ever) aspiring to "World Class" style, Toronto's Guild of Civic Art launched in 1905 a planning study for downtown -- acres of it swept clear by the Great Fire of 1904. Insurance atlases of the time outline vast swaths marked in fine script: "All gone."

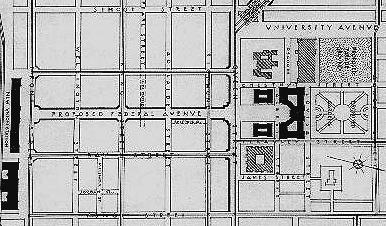

How convenient: the Guild hoped to modernize, improve traffic flow, and give grimy Hogtown some grandeur. As you can see below in a plan of 1911 -- with the avenue at last called University -- by architect John M Lyle.

Beaux Arts vision: John Lyle's Federal Avenue, new civic square & "New Union Station" -- his own, if not yet there. By 1919 it was; by 1965 Nathan Phillips Square & new City Hall would fill his proposed civic block. But his boulevard between was not to be.

Lyle's "Proposed Federal Avenue" split the block between Bay and York Streets, ignoring University Avenue but for a new "King Edward Boulevard" cutting in at Queen, where the avenue still ended. A new civic plaza would look down a long axis to the "New Union Station," not yet there but planned, Lyle its chief architect.

The block to be filled by that new station had been swept clean by the 1904 fire. Lyle would keep it clean. As architectural historian Douglas Richardson wrote in The Open Gate: Toronto Union Station: "When Beaux-Arts men laid their plans for the City Beautiful they were invariably impatient of interference from small businessmen."

Lyle's station did get built, Beaux Arts in its bones if dressed Anglo, devoid of French frippery. Finished in 1919, it didn't open until 1927 (for lack of a viaduct bringing tracks to its platform level); its 750 foot sweep along Front Street left no room, as Richardson wrote, for "the unsightly small stores that seem to form a parasitic growth around many large railway terminals."

Union Station did not, as planned, face up a grand avenue. It stared right across the street to the Queen's Hotel, in 1929 replaced by the Royal York -- biggest hotel in the Empire, if squeezed into the block between York Street and the planned Federal Avenue. But there would be no Federal Avenue: by 1950 the new east wing of the Royal York stood in its path, as other structures rising since 1911 had before.

Still, that grand boulevard had not been forgotten.

|

* Dreams dismantled

The Tories split up Ontario Hydro: one arm to generate power; one to distribute it; one to carry its debt (the third, of course, to remain public). On Dec 12, 2001 they put distributor Hydro One up for sale; in May 2002 they had sudden second thoughts. But, we're ever told, privatization is "inevitable." We look forward, like California, to higher bills, blackouts & bankruptcies. |

In 1929 Federal Avenue was reborn, in plan -- if rather transformed. Beaux Arts bones had grown new skin: Jazz Age "Moderne," Art Deco; even new bones in "buildings as mountains." (Lyle had a go with the Bank of Nova Scotia, designed in 1929 but shelved during the Depression, going up only in 1949; you can see it on the Downtown tour.)

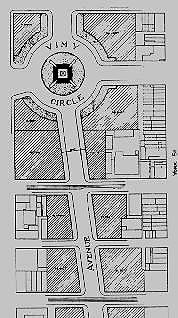

Toronto had also been transformed -- by World War One. Lyle's resurrected route was renamed for its battles: Cambrai Avenue, and -- where it encircled towers since built in its path (among them the Concourse Building, now facing the wreckers) -- St Julien Place. The city's biggest war memorial was to dominate a circle named for Canada's golden moment of the Great War: Vimy.

|

Plans Moderne:

Imperial visions; memories of war

Top left: View from King up the proposed Cambrai Avenue (Federal revived), making a "Park Avenue" sweep round a tower in its path. Below: plan of Vimy Circle, at Queen between Simcoe & York; the Avenue

extended south on a jog-- if then as Queen's Park Avenue.

Left: "Looking south across Vimy Circle," at its centre the Great War Memorial. |

The buildings around Vimy Circle were planned with a uniform cornice line 100 feet above street level, tall towers set above and behind -- just like Canada Life: its tower was meant to be much taller. One date set its fate, and the fate of these grand plans: 1929.

The Avenue came out of the Depression with a slight southeast jog below Queen (the planned Queen's Park Avenue, renamed); no circle; no memorial -- and just one modest bit of Moderne: the Parker Pen Building, gone by the 1980s.

North of Queen it was widened across its parallel street, leaving a median meant for people. Three lanes of one way traffic whiz by on each side; signs say "Walk" not long enough to let walkers cross the avenue in one go ("Pedestrians Obey Your Signals: Two Stage Crossing"; not lately fleet of foot, I am content to Obey). The median offers shorn grass, concrete planters, and benches rarely occupied.

The usual occupants are unable to stroll: they're dead, in bronze. South of Queen, his back to the lost Vimy Circle, stands Sir Adam Beck. In 1906 he founded -- under a Conservative government -- the publicly owned Ontario Hydroelectric Power Commission. His gaze is cast north, to the pink pile where modern Tories dismantle his dream in the name of "free" enterprise. *

Sir Adam presides over asphalt, cars, and concrete guarded by, as Bill Dendy said in Lost Toronto, "faceless office and institutional buildings typifying the worst clichés of twentieth century architecture."

It's a far cry from chestnuts blooming pink in springtime.

|

Civic celebration

My bit in the bid to save Union Station: conceived with my friend John Taylor who took the photos, edited by me with much help from contributor Douglas Richardson, published in 1972. For more on the book & its makers see Promiscuous Affections, 1971 - 1972.

"Une salle des pas perdus"

|

If I seem down on the monumental, let me assure you I'm not. Or not entirely: I once had a hand in efforts to save a monument, one you've seen here: Union Station. Grand plans of 1968 would have smashed it to rubble, six banal office towers rising in its place, its tracks redirected to a new "cost efficient" rail facility crouching far south of Front Street, reached by tunnels. Or cars.

Citizens fought off "progress," as they had earlier to save Old City Hall. Coming in from a train we are still sheltered by an arc of ceiling 88 feet high; stroll our way to Front Street past pillars, 75 tons each one, set deep in the earth. We enter our city like kings; we might have scurried in like rats.

Lyle's pure space has seen "parasitic growth," planted by business big and small. Hot dog vendors, common on busy streets downtown, are less egregious to me here than Bell phones set on "classic" pedestals, or the carbuncle once hunkered against those towering pillars, beaming out in bright orange "Budget Car Rental."

The Paris Opera, Tower Bridge, New York's lost Pennsylvania Station -- in his 1970 book The Necessary Monument British architect Theo Crosby said of them:

-

"Monuments carry a subversive message, of conspicuous consumption, of lost erudition, of values beyond the mundane. They are reminders of our better selves, our communal responsibilities, and of our present slavery to the requirements of the production process.

"Above all, they are enormous examples of an alternative mode of perception, of another set of priorities...."

Old monuments especially: old buildings, even small ones -- providing, Crosby said, "a key to our relation to the past and to the present." Grandeur may resist the messy interference of daily life; good urban streets, free of logic's grand plans, thrive on it.

I love standing in Union Station's Great Hall, bathed in its resonant echoes: une salle des pas perdus, as Beaux Arts boys liked to say: "a hall of lost footsteps." But I'm more often happy with the clomp of feet on Queen.

Postscript: In 2002 that "hall of lost footsteps" risks being lost to mall madness. Among its potential developers -- chosen by secret sweetheart deal -- is the son of Megacity Mayor Mel Lastman. For citizens rising anew, & how you can join them, see: Save Union Station (again). (http://www.saveunionstation.ca)

See more on:

Sources (& images) for this page: Theo Crosby: The Necessary Monument: Its Future in the Civilized City, New York Graphic Society, 1970.

Richard Bébout (ed): The Open Gate: Toronto Union Station, Peter Martin Associates, 1972.

Eric Arthur: Toronto: No Mean City, University of Toronto Press, 1964 (College Ave gate at Yonge; the Armouries).

William Dendy: Lost Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 1993 (first published by Oxford University Press, 1978; 1878 view, a lithograph by W Wesbroom; Vimy Circle & Cambrai Ave, by Earle C Sheppard).

City of Toronto Archives: The Architecture of Public Works: R C Harris Commissioner 1912 - 1945 (plan of Vimy Circle).

Douglas Richardson: A Not Unsightly Building: University College and its History, Mosaic Press, 1990 (Storm's painting; College Ave gate at Queen).

The Park Lots, in A line on a map (1793).

Taddle Creek & the University of Toronto, in

Landscapes lost, & found.

John Strachan & his Trinity College, in

York's fort; Toronto's reserve.

Sir Adam Beck & Tory privatizers, in

Citizenship, a chapter of Promiscuous Affections.

Go on to:

Glory of Empire

The South African War Memorial, & other monuments to lost boys

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/downtown/2puniv.htm

June 2001 / Last revised: November 4, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com