|

On the Origins of

TheBODY POLITIC Chapter 4

|

|

Pushing quarterly? (Beepers in bare times)

Issue 6, late 1972:

|

These would be hard years, the core group keeing TBP alive often small. But these years would also see people who shaped the paper for the rest of its life.

|

Burb meets Beepers (Nearly all of them)

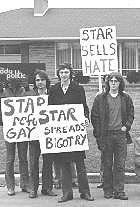

"The Star sells hate."

|

The Gay Tide case

For its sequence see Victories & Defeats, the online chronology from Flaunting It!, TBP's 1982 anthology. For full details see "Supreme Court dumps Gay Tide," TBP, Jul '79.

Baby steps

Late 1971 through 1974

The next three years would begin to show just what the people at The Body Politic might make of that destiny -- and how they would keep it in their grasp. These would not be easy years.

Meant to be a bimonthly, TBP would visibly surrender the effort by Issue 6, its cover showing not a two month date but a quarterly one: Autumn 1972. Issues 9 to 11 would give up even seasonal dating, showing only the year of publication. It would take until early 1974 to get back on a bimonthly schedule.

Issue 1 had been the work of nearly two dozen people. Of the 15 issues produced in the next three years, only two would have more contributors, not counting letter writers to the (nonexistent) editor. The core group truly keeping the paper alive was small. Often very small.

No one was paid. The idea must have been broached: minutes of March 18, 1974 record a motion "That under no circumstances will collective members be reimbursed for time lost from work due to work on the paper." It passed by a vote of five to two (with one abstention, likely the potential payee).

No one would be paid until late 1974, a pittance then to just one person, and just briefly. No one would get a regular salary until April 1976, again just one then, at $3,600 a year.

Writers weren't paid; for TBP's entire life they never would be. Nor were editors, photographers, layout sloggers, bookkeepers, phone answerers, floor sweepers -- and almost everyone at one time or another filled any or all of those roles.

The Body Politic's stock of human capital, later vast, would be rather thin for a time. Commitment freely offered was always the paper's one true asset: it was all an act of love. "Love is all you need".... Sometimes it's all you've got.

The Body Politic would have its first brush with notoriety in this period, attacked by the mainstream media if, for the moment, avoiding the wrath of the state.

TBP dealt with media hostile not only in their reportage (or lack of it), but in business practice as well. Many gay groups were denied even tiny classified ads offering nothing more shocking than a phone number.

In 1974 one such refusal, by the Vancouver Sun of a subscription notice for the Gay Alliance Toward Equality's Gay Tide, would lead to the first gay case ever to reach the Supreme Court of Canada. It would take until 1979 to get there. GATE lost. (But, with their right to discriminate confirmed, the Sun later accepted GATE's ad.)

In Toronto one big daily used its control of Newsweb Enterprises to cancel printing of TBP just as an issue was set to go to press. That was Spring 1973, its lead story reporting "Why 8's late" with shots of a demo outside The Toronto Star.

After continued ad refusals (in an October 1974 editorial The Star drew the line: we may be liberal "But we stop short of encouraging the spread of homosexuality" -- especially to kids!), TBP did a four page extra titled "The Star Sells Hate" and picketted its publisher's suburban abode.

Yet these same years set patterns the paper would follow for the rest of its life. Or rather, they saw the people who would set those patterns.

What The Body Politic would become depended in part on shifting social forces, but perhaps more significantly on who came along to face those forces: who arrived and who left; who had ideas they could put to work; who had the power to shape this medium to meet visions of their own.

From the paper's second issue through its 10th, the collective would see 23 new members. For the record here are some of their names, and something of who they were (where I know).

For some I know only names: Ray Gunderson, just Issue 2. Kathy Picard, a heterosexual woman who wrote about being "schizophrenic" (the quotation marks her own), on for Issues 2, 4 and 5; Donya Peroff, who wrote mostly fiction; Issues 4, 5 and 6 but on the collective only for 5.

Doug, Brian (not Waite, another, just first names listed), Walter Klinger, John Powers: all on for Issue 3, then gone. Peter Lakin (a flatmate of Herb Spiers's) and Bill Mitchell from 4 to 7 (Bill aka Willy -- or Martha; he moved to New York and became Max).

John Scythes, contractor and communal housemate of Jearld Moldenhauer, Issues 5 to 11, on the collective for the last three (but on the scene to this day as renovator to the community and, since 1991, owner of Glad Day Toronto).

Linda Koch, coming from the left for Number 7 and going back to it after 11, leaving the collective, but for brief moments, entirely male until 1978. Darryl Tonkin, an artist who arrived the same time as Linda and stayed just one issue longer. Walter Blumenthal (later Bruno), another sober leftist who came on at Number 10, on the collective by 12, gone after Issue 15.

Veteran activist George Hislop, while never on the collective, did write for early issues. In one he got slagged as CHAT's president; after that he stayed away -- until his return as a news subject, perennially from the late '70s.

As Dorothy said in Oz: My! People come and go so quickly here. Of those 23, seven were collective members for only a single issue. By early 1975 just five of those 23 would still be on the collective; just two or three others continuing as contributors.

Membership criteria were vague: for a while working on a single issue was all it took to be counted among the collective. In time (in fact a few times) criteria changed, making a stint on that ostensibly august body a more serious sort of commitment; then, for a year and half, there were no new members at all.

Some people who arrived during this time were committed indeed. Amidst this flux and despite formal equality, some animals would clearly become more equal than others: staying power meant true power to shape the paper's destiny. And some stayed a very long time.

|

Dynamic duo (Ex-couple; constant pair)

What, me worry?

Lit-critter to "big queer":

|

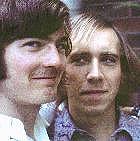

Herb Spiers recalled Ed & Gerald's arrival: "This is a one- two punch. Here are two people involved & they could write!"

Gerald Hannon & Ed Jackson

Information on and quotes from Ed and Gerald come from my years of acquaintance with them, and some specific sources: "In Your Face," an article on Gerald by Sandra Martin in Toronto Life, Jul '96; a taped interview I did with Ed on Sept 3, '95; notes I made after a dinner conversation with him on Apr 26, '98; and an extensive account of his experiences before The Body Politic, sent to me by e- mail May 6, '98.

Much info on and quotes from other new Beepers below comes from Gerald's 10th anniversary article "Who we were; Who we are" (TBP, Jan / Feb '82) and notes and tapes of interviews done for it.

Ed Jackson and Gerald Hannon arrived as a pair. Gerald had grown up in Marathon, a pulp mill town on the north shore of Lake Superior. He was always an outsider there, the butt of jokes, "dreamy and dozy" as he himself said years later.

He would spend weekends listening to classical music on the radio; he once told me that Clyde Gilmour on the CBC's Off the Record, broadcast from Toronto, seemed to him the voice of civilization.

Gerald escaped to civilization in 1962, getting a scholarship to the University of Toronto's St Michael's College -- a Catholic school, Gerald once an altar boy. He had heard of homosexuality by then, had, as he later said, "begun to make a connection between the concept and me."

But it was not a comfortable connection: in private moments he would say to himself, "I'm a homosexual" -- but then let the thought pass: "I couldn't continue to think about it." He studied philosophy, graduated in 1966, took a clerical job and, only half willingly, found a girlfriend.

Ed Jackson had finished his BA at the University of New Brunswick in 1966, major in English, minor in history; he wanted to go on to graduate work, become a "lit critter" as he later put it -- and get out of Fredericton.

"I was already aware I was gay, but not completely happy about it. I believe I had already read John Rechy's City of Night and half thought that was the kind of underworld I was going to have to live in."

Ed had had an intense if tentative affair with a fellow student in Fredericton. For some time after they first had sex, Ed said, "I was very happy and positive about being gay. It seemed so right, so good." But that man later asked him: "What are you going to do about your homosexual problem?" Those words burned inside Ed for a long time.

He got to graduate school at the University of Toronto on a scholarship and student loan. In some of his classes there was a man who, after years as a teacher and librarian, had decided to further his education. Philip was twice Eddie's age -- "42 seemed unimaginably old to me then," Ed says, "but he could instantly read the invisible print across my forehead: big queer."

Philip was also "fascinating and intelligent and articulate and, eventually, made the best case for homosexuality I'd ever heard. He was the first person to talk intelligently and answer all my doubts about being gay, but I can't remember how we finally crossed the threshold of my reticence to talk directly about it, and then to have sex.

"He really was a gay liberationist before there was such an identity." (He still is, if a bit shy of public identity; some habits, hard learned, can have odd staying power.)

Ed never got his MA, falling short by one essay owed to Northrop Frye. After coming out for good he lost interest in graduate school and decided to get a job. By 1968 he was in adult education, teaching English as a second language to immigrants, many of them refugees fleeing the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia.

There he found another teacher, Gerald Hannon.

Eddie got Gerald out of the closet, into bed, and into a relationship -- soon as friends, not lovers -- that would last for decades.

In the fall of 1970 they decided to take a year off and travel together. They headed by bus to Mexico, where Gerald had spent a summer as a volunteer teacher, learning Spanish in the process. Another long bus ride later took them to New York.

There they hoped to find the gay liberation movement, in fresh flower little more than a year after Stonewall. But they didn't, not then. They would later, via a cheap transatlantic flight to London. There they marched in a Gay Liberation Front demonstration, their first ever and so frightening in prospect that they went first to St Paul's Cathedral to calm themselves and -- with no hope of divine intervention -- find their nerve.

Back in Toronto in the fall of 1971, they soon found CHAT, TGA, and The Body Politic with Issue 1 already out. At a meeting at Jearld Moldenhauer's, Gerald agreed to write an article for the paper, Ed a review. At a later meeting they read their works aloud.

Herb Spiers remembered the moment: "I thought, well my god in heaven, this is a one-two punch. Here were two people who were involved and they could write." Paul Macdonald remembered that, too: "By Issue 2 the paper had attracted more literary types" -- citing Ed and Gerald among them.

He might have cited another recent arrival as well.

Hugh Brewster was fresh out of school, with a degree in English from the University of Guelph and looking for a job in publishing. He had been involved with the gay group there and soon found its match in Toronto. At a meeting of UTHA Hugh met Jearld Moldenhauer, who had with him the first issue of The Body Politic.

Jearld was interested in Hugh; Hugh was interested in Herb Spiers. But, as Hugh later said: "It wasn't just attraction for him or anyone else in particular that made me come around. The world of the bars and all the rest of it didn't appeal to me very much," but the activist scene was full of people who were "dynamic, committed, attractive."

Hugh was soon part of that scene, caught up in meetings four or five nights a week with CHAT, Toronto Gay Action, and The Body Politic.

|

Peripatetic Aussie (Toronto on his itinerary)

Dennis Altman:

|

"Of all the cities I know, Toronto seems to have the strongest sense of gay community, to be a place of constantly re-imagining the social meaning of making sexuality central to one's sense of the world...."

Dennis Altman

in Defying Gravity:

A Political Life, 1997.

|

Camp stalwarts (If not for long)

"Team Canada's groupies":

|

"I noticed plenty of can openers, but could not spy any wire whisks. 'How can you make a soufflé without a wire whisk?' I asked. 'What's a soufflé?' replied Helen."

Hugh Brewster

visits the "Heteros as

Just Plain Bores."

Ed, Gerald, Hugh and the rest of the (surviving) gang did paste up for Issue 2, David Newcome teaching them, in CHAT's office at 6 Charles Street East, a grand former postal station with Cinecity, an art cinema, downstairs. The next few issues would be produced among the warren of rooms in the basement of the new CHAT Centre at 58 Cecil Street.

Running the paper was very much a peripatetic affair. "The whole Body Politic file," Paul Macdonald said, "was about the size of a briefcase at the time. You could fit it in the trunk of a car.

"We were truly an underground paper: nobody could have raided us then [Paul was speaking in 1981, the Toronto bath raids and one on TBP in 1977 very much on the mind] because nobody could have found us."

Gerald Hannon's first article was "Porn at the Clarke," tales of being a paid guinea pig at the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry wearing a "phallometer" over his penis ("feeling rather like Frankenstein before the switch was thrown") to measure his response to pictures of naked people.

Ed Jackson's review in that issue was of Arthur Bell's Dancing the Gay Lib Blues, tracing the first year of New York's Gay Activist Alliance: some useful lessons, Ed said, but "finally only mediocre journalism."

He had a more positive take on Dennis Altman's Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation in Issue 3. He ended it with a note: "Dennis Altman plans to visit North America in May and The Body Politic will do its best to persuade him to include Toronto on his itinerary."

Dennis showed up not only in May 1972 but many times later, in person and in print: he would be a periodic essayist, reviewer -- and review subject -- well into the 1980s.

Hugh Brewster made his début in "The Non-urban Gay Ghetto." Back in the small town where he had grown up he found a hotel "ladies and escorts" lounge (the integrated part of Ontario bars; tap rooms then, like the one at the back of The Parkside, were for men only) where a few local gay people

- "...had created their own mini gay bar out of two tables in the corner of this dingy room. ... As I sat there among them the fact that depressed me most was that I knew scenes such as this one were being played out in a thousand smaller centres across the country, in the dark corners of beverage rooms from North Bay to Nanaimo."

More characteristic of Hugh was attention to the urban gay ghetto and its culture -- as something more than a target of attack. He got the centre of Issue 3 for "Counternotes on camp," a look at Susan Sontag's famous notes of 1966. There she had said that "camp is a solvent of morality. It neutralizes moral indignation, sponsors playfulness."

Hugh agreed: "Camp could be an invaluable activist tool, if we were able to turn the cleverness of bitchy, intramural gay humour against straight society rather than upon each other."

But it was not to be. For some around TBP camp was self oppressive, old fashioned -- positively cringe making. Mind you, some of those critics could camp up a storm. But they rarely did it in print: it might put off more serious left leaning politicos -- if not necessarily "the masses," the urban gay male one, anyway, for whom they so often presumed to speak.

Hugh, with John Forbes (Twilight Rose the paper's camp stalwart), would have a last go at the end of 1972, the back of Issue 7 parody of a Maclean's cover: both in drag as "Team Canada's groupies" (our hockey stars had beat the Ruskies that year). Inside, Hugh's "Couples: Portrait of the Heteros as Just Plain Bores," sent up a Maclean's profile of gay couples as "just plain folks," CHAT's George Hislop and his lover Ron Shearer inevitably among them -- for most media then "Toronto's only homosexuals."

Hugh visits Mack Truck and Helen Bed, lends a hand with dinner. "I noticed plenty of can openers ... but could not spy any wire whisks. 'How can you make a soufflé without a wire whisk?' I asked. 'What's a soufflé?' replied Helen." The terms "ball" and "come on" were footnoted as "hetero slang" and helpfully defined.

But after that both Hugh and John left the collective -- and we'd not see the likes of that my dear, for quite some time to come.

John would return, his sensibilities intact, with a few pieces in the late '70s. Hugh would become a Buddhist, move to New York, and return here to a very successful career in publishing, if not of things gay.

I'd met Hugh Brewster in late 1971, at Alan Falconer's place just upstairs from mine. It was a CR session. Consciousness raising was a minor rage of the early gay and women's movements, a way to "get in touch with our feelings." In Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation, Dennis Altman quoted Vivian Gornick, from a 1970 article in the Village Voice:

- "Feminism, for me, is the journey deep into the self at the same time that it is an ever increasing understanding of cultural sexism ... and, more than anything, the slow, painful reconstruction of that self in the light of the feminist's enormously multiplied understanding."

To those who lived through the therapy soaked '80s this may sound familiar -- but for the clear connection of personal growth with political awareness. That link, later lost in sheer self absorption, was central to all the liberation movements of the early 1970s. As a statement from one gay men's CR group put it, in Karla Jay and Allen Young's 1972 Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation:

-

"Consciousness-raising is unlike therapy or encounter groups. ... Therapy doesn't make clear that the relationships which cause us to have difficulties are determined by the anti- homosexual atmosphere that surrounds us. We have been defined by the churches, by psychiatrists, by sociologists....

"Through the process of consciousness-raising, we have begun to define ourselves."

Hugh had himself defined already, thank you very much. When someone put on a record of Laura Huxley, wife of Aldous, droning on to lull us into meditation, he giggled. So did I. I took him home (just downstairs) to bed. I'd see quite a bit of Hugh after that, and through him meet more Beepers.

At a June 1972 party at Hugh's, I met a proto-Beeper. I didn't know that then, just that Don Bell was sweet, handsome, shy -- too shy for a too well organized orgy going on in another room. We talked; when he left I followed him -- to what would become a year of fabulous fuck buddyhood.

Don once made a calendar for me, a computer printout. Computers were what he did, by mid 1973 doing them for TBP, automating the subscription list. He'd be on the collective then, leaving it a year later. But he didn't leave in spirit, going on doing subs to late 1978.

By then he'd be better known as a disk jockey at community dances, and sometime manager of a bar or two. Don would be one of the first people I knew well to die of AIDS, in May 1985, then 34 years old.

|

Domestic digs (TBP & friends)

From Twilight Rose

Seaton South:

|

|

More domestic digs (& household politics)

Just another evening at home:

In mufti:

"Piggy & Bunny":

|

Bunny remembered

On October 21, 2002 Robert Trow, living with HIV since the early 1980s, suddenly died. Not of AIDS, but a brain aneurysm.

At his memorial, Gerald Hannon -- the love of Robert's life and he of his, long after they were "lovers" -- spoke "of the worlds that Robert was, and of the worlds that he helped to create, and of the worlds that helped to create him."

Worlds of our own creation.

Creating us.

Jearld Moldenhauer had moved to 4 Kensington Avenue in June 1972, the house holding Glad Day's first real bookshop. It was also home to a gallery, Kensington Art Associates, among those associated Amerigo Marras, whose drawings had graced early issues of TBP. Also to Jearld, Amerigo, and a revolving crew, one of many gay group households of the day.

And to The Body Politic, put together in a backyard shed -- distributed from there too, sometimes, Gerald Hannon recalls, hauled out in a bundle buggy and a little red kiddie wagon.

It was there Ed Jackson first saw Merv Walker, "completely enchanted," he'd later say, by the sight of him backlit against that back shed's windows. Merv had arrived in town just shortly before, driving in from Saskatchewan with Erv Warner. (Yup: Merv 'n' Erv.)

He had grown up on a farm in Kamsack; Erv was from Prince Albert. Both had been in on the birth of the first gay group in Saskatoon and now wanted to see what was going on in Toronto. They spent their first night here in the CHAT Centre's basement.

Erv -- soon rechristened Tom Warner -- would have quite a career in the city, not only with The Body Politic (involved from Issue 8, on the collective to early 1975) but on other fronts as well. In 1993, very much a veteran activist by then, he would become the first openly gay man to serve on the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

Merv had seen TBP, recalling in particular a coming out letter Ed had written to his parents. But he later said he "didn't really have an impression of the paper before coming to it."

He made quite an impression himself: 19 years old, quiet but engagingly beautiful -- and hugely smart. Ed's enchantment would lead to a relationship of some years. (So: Edwina & Mervina.)

Merv was on the collective by Issue 7, late 1972, and with one brief break would stay there until Issue 47 in late 1978, designing and producing the paper and doing some writing, too. He would later move to Vancouver, San Francisco and Montreal, but he'd be back in town to run his own design company -- for which I'd work in the mid '80s, both of us TBP trained.

The romantic backlighting of those shed windows also had a more practical use, gridded page flats held up against them to get type and images lined up. Merv would later build the first proper light table, one he (and I and many others) would use for years.

That was at 38 Marchmount Road -- in the basement (yet another) of another gay group abode. Merv and Eddie lived there, Herb Spiers, Paul Macdonald, and Gerald Hannon, too.

They came to be called "The Kitchen Collective," suspected (and it was likely true) of conducting much of TBP's affairs over the breakfast table or down in the cellar. (A critic of the time, likely unaware of these circumstances, would call the gay movement "mushrooms growing in a damp basement.")

And they were collectivists at home: domestic ones. Ed Jackson would later write about the "politics of housekeeping."

- "We know where it all started. There is this remarkable little institution known as heterosexual marriage. It was devised so that there would be an inequitous division of labour between the husband and the wife. One of the things that the woman does, without any pay and in exchange for room and board, is all the housework. Men do not do such work."

Gay men living together had to -- and could, as Ed wrote, "explore the tremendous potential for equality in our relationships. Nothing is fixed or imposed, nothing is assumed." Yet somehow the dishes got done.

People in such households also explored politics well beyond the kitchen sink. Many were nests of activists, political and cultural, vets and novices together -- learning together. Many newly arrived "roomies" soon became comrades. It's how we raised our kids.

In the spring of 1973 Jearld Moldenhauer found a new address. It would be The Beep's too: 139 Seaton Street, half of a duplex southwest of Parliament and Dundas Streets. Over the years it would house a revolving collective menage, Jearld, with co- owner John Scythes, always at its centre.

Later there'd be another up the street, at 188 1/2. The two were dubbed, to distinguish them, Seaton North and Seaton South. Between them, they gave this town (and even places beyond this town) noted writers, editors, book sellers, community activists -- and lots of Beepers. John Scythes and Jearld Moldenhauer still share a house with others. It's more grand, rather less collectively run -- but still a hotbed of activism.

Someone once said to Gerald Hannon, speculating on the notion of collectivity: "I suppose you all sleep together." Well, not all. But some. In 1973 at 38 Marchmount, later at 48 Simpson where that menage moved, Gerald was sleeping with Robert Trow.

Raised in suburban Thornhill, Robert was in library science at the University of Toronto. His first Beeper was Hugh Brewster, met at a York University Homophile Association dance in late 1972. Later they met again, at a CHAT dance, held by then at a modern Unitarian Church at 175 St Clair Avenue West. David Newcome was there too. That night, Robert went home with David. But he'd find Hugh again.

They went together to see a play by John Herbert, who'd done Fortune and Men's Eyes in 1965 (staged in New York, 1967; made a move in 1971). This one was Born of Medusa's Blood. Some of Hugh's fellow TBP types were there, and from that event they would take two things.

One was famous lines tossed off for years to come: "On your feet, foreskin!" and "Do you suck, fuck, rim or blow?" The other was Robert Trow. It was there that he and Gerald Hannon met.

Robert was in the paper by the spring of 1973, his début TBP's first porn review, of Wakefield Poole's 8mm Boys in the Sand (which the police came to seize but grabbed the wrong reel, Bronté, not boys: Jane Eyre).

By early 1974 he was on the collective, there on and off -- he one of the first to find influence whether on the collective or not -- but never gone. Robert would be master of distribution for the rest of The Body Politic's life. He was also that first paid person, from November 1974 if not for long, getting all of $80 a month to be office manager.

Despite having degrees in both library science and history, Robert would make his career as a paramedic, from 1976 with Toronto's Hassle Free Clinic. Born a hippie altervative, it came to see more gay men than any other medical facility in Canada. Robert Trow would play a key role (along with other early Beepers you've met above, and will below) in the creation of the AIDS Committee of Toronto.

|

Utterly logical (Even when life isn't)

Ken Popert

|

Ken Popert, as he wrote years later in a brief autobiographical note:

- "was born in Toronto in 1947. He began to realize that he was inescapably different around the age of 14, when his Christian fundamentalist bottom boy sat up in bed one morning after their weekly sadomasochistic fuck and said: "You're a homosexual." After pondering that point for few years (with the copious aid of LSD), he used the occasion of leaving home for graduate school to come out."

That graduate school was Cornell, where Ken studied linguistics. He joined the Cornell Student Homophile League in late 1968, edited its newsletter, and met its founder -- Jearld Moldenhauer. Back in Toronto in February 1973 he found Jearld again, and The Body Politic.

Ken had no reputation as an acid head by then; acid tongued was more like it. In the paper's 10th anniversary issue in late 1981, Gerald Hannon recalled Ken years before as:

- "counter-culture skinny -- though that skinniness and the long since vanished ponytail were the only significant Popertian concessions to counter- culturalism. He is possessed, in fact, of the coolest, most clinical intelligence of anyone on the paper. It has its drawbacks: You will sometimes hear from Ken an argument that is utterly clear and irrefutable -- but bloodless, and true to everything but the way people operate."

Ken was on the collective by Issue 9. He was the first to bring order to the paper's layout, "inventing" the news, as he later put it, moving it right up front -- where it stayed for TBP's entire life.

Ken would quit the collective twice but he never really left -- not when the collective disbanded in 1987 after The Body Politic was gone; not even to this day. He is now president and executive director of Pink Triangle Press, publisher of Xtra in Toronto and sister papers in Ottawa and Vancouver.

In April 1973, at a gay festival at Cornell, Herb Spiers met Jim Steakley, digging in German gay activist history.

Herb convinced Jim to do graduate work in Toronto, his most visible work a series of articles spanning three issues of TBP (9 to 11), 13 pages, and more than 70 years of German gay history -- from Karl Heinrich Ulrichs in 1864 to the birth and death of the Third Reich. Those pieces became a book, The Homosexual Emancipation Movement in Germany, published by New York's Arno Press in 1975.

This was not the first historical work in TBP. In Issue 8 Bob Wallace (we'd call him "Bob Wallace, librarian" to distinguish him from the later "Bob Wallace, playwright") had devoted nearly four pages to Nellie McClung and the early 20th century women's suffrage movement in the Canadian West. These early pieces, the space and care they got, showed a commitment to history that would become a hallmark of The Body Politic.

Jim Steakley would be on the collective for five issues, to mid 1974; he would continue writing for the paper much longer, from the University of Wisconsin.

|

Ghetto critic (To leather boy)

Radical gone clone:

|

|

Graphic zaniness (& coherent order)

Burkers get the finger:

New-look Beep:

|

Ron Dayman made his début in Issue 8: a lettter from France. He was Canadian, studying in Aix en Provence. He lauded The Body Politic on its "continuing high quality" but also warned of "several reactionary leanings" -- the worst evidence a map in Issue 7 of "Toronto's Gay Spots."

- "I think you owe readers an explanation of your attitude toward these gay ghettos. Surely it is not your role to encourage their existence. It's time homosexuals ceased stalking behind walls and took to the streets."

Ron would be in Toronto a few months later; by Issue 12, March / April 1974, he'd be on the collective. He would stay there only three issues, but would continue writing for the paper well into the '80s, from Ottawa and later Montreal.

Ron, too, would make a significant contribution to history, as the founder of the Canadian Gay Liberation Movement Archives in 1973. It is now the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives -- one of the largest resources of its kind in the world.

In time Ron would soften his critique of the ghetto and get into leather. He died some years ago.

They had all become collectivists by the end of 1974. Some others around by then had not, though they later would -- and to lasting effect.

On page 1 (the opening spread, the paper folded to make the cover) of Issue 4, May / June 1972, there was an elegant waiter giving the finger to "Burkers" -- the Edmund Burke Society, who (as the "Western Guard") had attacked a forum on homosexuality, gassing the crowd with Protect U, a civilian brand of Mace.

It was signed with what looked like "OT 72." The masthead listed someone called just "Gary." It was Gary Ostrom. His work would appear in TBP to the end of the paper's life, from tiny column fillers to multi panel strips filling whole spreads. His line would become more economical than in 1972, characters and their expressions created with just a few deft strokes.

They were funny, but rarely in an obvious, easy way. Gary's take was quirky, lateral, odd -- hence much funnier than most. TBP, noted as a sober read, often tried for light bits, too often forced: to many Beepers (in print at least), humour didn't come easily. Gary didn't have to try: he had bizzarre down by nature.

Gary would be on the collective from early 1976 to mid 1978. Then he'd move to San Francisco (still there today, if now calling himself Frederick) but go on sending stuff, all the way to 1987.

Kirk Kelly's name shows up in the masthead at Issue 7, late 1972, his exact role unclear -- but it must have had to do with design. That's what he did, later running a big graphics firm in Montreal (where Merv would work with him).

Kirk may have had a hand in cleaning up TBP's look when Ken Popert reordered it at Issue 9. By the October 1975 issue (done in August and dated two months ahead) his hand would be obvious: the paper got a new page format and a new logo. He'd do it again three years later, TBP becoming a big, flat, unfolded magazine (though we'd still call it "the paper").

He was in town often, on the collective from that first remake through the second, even when he wasn't on site. His presence was always bracing: forthright, witty, more hard nosed that most collectivists. He was a great designer -- and a great teacher: he'd be very much mine.

Kirk later married a wonderful woman, strong enough handle him.

On the collective or not, Michael would be a constant force, his impact on TBP & its community enormous.

Michael Lynch, originally from North Carolina, taught English at the University of Toronto. He was active with GATE -- though until 1973 he'd never had sex with another man.

Toronto's Gay Alliance Toward Equality won a big victory that October, making this the first city in Canada to ban anti gay bias in civic employment.

Michael was writing for The Body Politic by then, his first work a review of The Male Muse, a poetry anthology, editor Ian Young. "So gay, so blond, so neat," the piece was titled, Michael not impressed. Ian was not amused -- if forewarned: Michael's review was followed on the page by a letter from Ian, to "Members of the Bodypolitbureau." Michael said he was "sorry to offend."

He would rarely offend, but often incite. He'd be on the collective for just a year, from mid 1976, but -- like Robert Trow, on the collective or not -- he'd be a constant presence, his impact on the paper and the entire community enormous. You can see much more of Michael, and what he achieved, in Promiscuous Affections.

You'll also find there another Lynch: Stefan, Michael and Gail's son -- a baby Beeper, you might say. Around the office from age 5 or so, he would grow up a gay liberationist. A heterosexual one as it turned out, if certainly not straight.

|

International liaison (Their work, that is)

Richard Fung and Tim McCaskell:

|

Tim McCaskell, from rural Beaverton, Ontario, had come out for Toronto's Gay Pride march in the summer of 1974. He had "worked a bit" as he'd later say at Guerilla, "so I could do that sort of thing," soon doing it at The Body Politic.

"It was very important to my coming out," he said, "the people there were inspirational. It was pleasant, people were fun and laughed a lot." Tim could certainly make others feel amiable. Gerald would write in 1981:

-

"Someone, perhaps he was little derganged, once told me that he had heard there were only three criteria for collective membership: looks, looks and looks. Perhaps he knew Tim McCaskell, who is always beautiful no matter how unfashionably he dresses, and very often otherwise, even given his incipient authoritarianism. I console myself with the knowledge that he spells extremely badly.

"He is one of our bona fide politicos. He knows from Marxism, has deep connections with Toronto's immigrant communties, and has done his tour of Third World countries in the throes of revolution."

Tim would join the collective in late 1975, the first new blood in more than 18 months. He might have joined sooner but for his Third World tours; they'd resume, to Africa and India, Tim gone for a year. He'd be back in time for TBP's great legal tour, launched December 30, 1977 -- but you'll see all that in Promiscuous Affections, and more of Tim, too.

It was Tim, more than anyone, who made The Body Politic a medium of international scope, writing on and sometimes from the countries he visited and, until he left a dozen summers after he arrived, compiling and writing (if not copy editing; there was that spelling) news from around the world.

Tim worked (and long would) for the board of education, his focus kids from the margins, the gay margins included. In 1988 he would be among the founding members of the shit kicking AIDS Action Now! -- one of many Michael Lynch inspirations.

Richard Fung, a renowned film and video artist, wrote for TBP and, like many in its extended family, was a major influence on the paper and its communities -- Richard key in reminding us there was more than one. He and Tim are together still.

|

A real office at last (If less one likely tenant)

TBP's first office:

Glad Day:

|

So, these are the people from these few years who would go on to shape the life of The Body Politic for years to come.

One there then would not: Jearld Moldenhauer.

In April 1974, with domestic confines getting cramped at 139 Seaton, the collective began looking for new space. By May 28 they had secured 193 Carlton Street, a ground floor storefront, to be shared with GATE Toronto and the Canadian Gay Archives -- then a small shelf of books and two drawers of a filing cabinet.

It seemed a perfect location for Glad Day too, a storefront after all. At 139 Jearld was selling a few books and, in between, doing work on the paper. "The two seemed very directly related," he said years later, "basically doing the same sort of work, trying to disseminate information, change people's lives. It made sense for them to be together."

But they would not be. Minutes of May 28 show a decision not to let Jearld run Glad Day at 193 Carlton. At the meeting of June 4 Jearld announced (in absentia, by memo) that he was taking a leave of absence for two months.

On June 25 the collective pondered how to remove members -- a thing they'd never pondered before (or much even later). On July 29, a motion: "That Jearld Moldenhauer be confronted and asked what he considers his status on TBP / whether on leave of absence and if so when he plans to return."

He never did. Jearld had to choose: his livelihood depended on Glad Day; he couldn't do that and TBP too if they weren't in the same place. He chose Glad Day -- as people had known he must.

Jearld would later say he'd been "assassinated," the issue of a store in that storefront simply a pretext "to eliminate me." In essence, if perhaps not detail, it was: Jearld was (and remains) a prickly character. He'd once say: "I'm not sure how people perceive what they call my 'abrasive' personality. I mean, from my perspective it's just that, I don't know -- everything just comes out upfront."

He chalked it up in part to being American. Now, for some collectivists more leftist (and cautiously Canadian) than Jearld, that would not do.

In 1981 Gerald Hannon asked Jearld Moldenhauer: "Did you partly want to leave youself at that time?" "No," he said. "No, it was my life. I mean, it, it really -- it really shattered me, you know. For a long time."

The Body Politic would go on, if without its founder. Jearld would go on too, Glad Day, by 1979 in Boston as well as Toronto, ensuring him a more than adequate livelihood. And letting him, still, change people's lives.

Go on to Beyond

Go back to Introduction / My Home Page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/oldbeep/baby.htm

January 2000 / Last revised: September 22, 2003 / Minor fix: August 11, 2007

Rick Bébout © 2000-2003

rick@rbebout.com