QUEEN STREET

Downtown

Private property;

public life

The city indoors: The Eaton Centre &

"Toronto's Downtown Walkway"

|

The "street" indoors: 2001

The Eaton Centre: seen from its south end at Queen, Canada geese dropping in (Michael Snow's "Flight Stop"); its open court halfway to Dundas, a third level below -- beneath "eatons" at its north end another below that. |

At Yonge and Queen on a summer afternoon, I'm stopped by a cute young couple, their moves reading tourist, the accent American. They ask me: "Where's the mall?" I ask: "Which mall?"

"Any mall."

I point west to the glass arched pedestrian overpass spanning Queen. "Right there," I say, "through the doors under the north end. You'll be in the Eaton Centre."

They'll be among the 19 million tourists who flock there each year: the city's main attraction, more a "must see" than the CN Tower (which you can't avoid seeing at least). And more than 30 million locals who annually enter its doors -- counting multiple trips; I must count for a hundred or so all by myself.

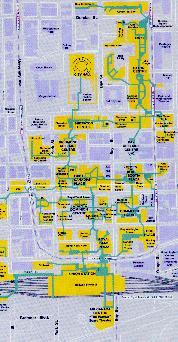

Opened in 1977, expanded in 1979, the Eaton Centre covers almost the entire block from Queen north to Dundas on the west side of Yonge Street, a stretch taking in two subway stations. At the time, counting Simpson's (linked by that bridge) it was, at 2.8 million square feet, the biggest shopping centre in the world.

No more: West Edmonton Mall passed it in 1986; Mall of America's 4.2 million in Bloomington, Minnesota took the record in 1992. But it's still big: more than 250 vendors on three levels, four with "Level 0" below Eaton's own nine floors; two Gaps, two Levi's Originals, three "Oh Yes Toronto!" -- tourist trinkets, sales tax refundable to those who qualify; two food courts, two McDonald's, three Second Cups, just one Starbucks. It's still among the busiest malls anywhere.

And it's smack in the heart of downtown.

We think of "the mall" as suburban. Quintessentially. Mostly we're right. Since the 1950s they have dotted burbs everywhere: first as strips fronting streetside parking lots (in Toronto Sunnybrook Plaza, 1952); as enclosed, climate controlled complexes set amidst acres of parked cars (Thorncliffe, 1961); as vast regional centres anchored by big department stores (Yorkdale, 1964), sometimes multi-level (Fairview the first here, in 1970 -- or so some people think).

We don't think of malls as "the city." "Doing downtown" has meant doing its streets, as Torontonians long have. In carriages on King, first street to draw "the carriage trade," its Golden Lion "the finest retail clothing house in the Dominion," the Golden Griffin a "splendid emporium" (as Eric Arthur said, "shop seems so inadequate a word"). On Yonge south of Queen, where Timothy Eaton first offered "Goods Satisfactory or Money Refunded" in 1869.

And, from 1883, at Yonge and Queen: Eaton's moved to its northwest side, the Robert Simpson Company south since 1881 -- twice burned out, the current store dating from 1895 and 1912. There they stayed, Canada's biggest barons of retail facing off for a century across one not very wide downtown street.

They still do -- if not quite. In 1978 Simpson's was bought by the Hudson's Bay Company, "founded 2nd May 1670" its signs proudly say, and Pro pelle cutem: "For fleece, skins." Born of the fur trade, until 1870 owning outright half of what is now Canada (if itself now owned by the Thomson media empire) -- it is to most just a department store: "The Bay." In 1991 that name replaced Simpson's on its flagship downtown emporium.

In the late 1990s Eaton's fourth generation bankrupted Timothy's empire: the signs still say Eaton's (if trendified to "eatons"), but the store is owned by Sears.* The Eaton Centre belongs now to the Toronto Dominion Bank (25%) and Cadillac Fairview Corporation (75%), one of the world's biggest developers. Of, among much else, malls -- with nearly 10 million square feet south of the border.

|

Doing downtown

Left: "Doing King Street," carriage trade caught (on foot) by H deT Glazebrook, 1879. And Doing Eaton's, along Queen -- before Simpson's: fence & gate fronted Knox Presbyterian, its land leased (not sold) to Robert Simpson for his store. Below: Same stroll, 2001. The Bay & the Eaton Centre bridged; shoppers crossing Queen here get their own traffic lights -- just yards from the crosswalk at Yonge.

|

|

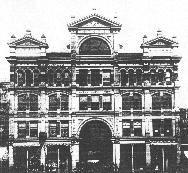

The "street" indoors: 1888

The Toronto Arcade, 1883, here five years old: three levels, slylit; out of the weather if not "climate controlled." |

|

The street outdoors: 1888

The Toronto Arcade facing Yonge, at 131-139 -- the low pediments left & right in fact false fronts. |

Indoor "streets" lined with shops tucked safely out of the weather were in fact born very much "downtown." And long ago: the Passage Feydeau in Paris, 1790; London's Burlington Arcade of 1818 (I bought a sweater there in 1975; still have it); most famous the Galeria Vittorio Emmanuelle II in Milan, opened in 1867.

We got one just 16 years later, grand enough for its time and place: the Toronto Arcade. Since 1958 its modern succesor has stood on the same spot, south of the Eaton Centre if on the other side of Yonge, facing west down Temperance Street (you can see it in "Mad for 'the show'") -- barely noticed but by locals once glad for its Loblaw's groceteria, now gone.

In its day no one could miss the Arcade. As Bill Dendy wrote, "such an impressive interior space had previously been found only in a few of the city's churches and public buildings." Its "rich detail and play of natural light" were a big draw. Much as the Eaton Centre is today, and for much the same reasons.

But Yonge Street declined as a shopping mecca. By the early '50s the Arcade was vacant, in 1955 torn down.

Civic fretting over that decline in fact gave birth to the Eaton Centre. Or the idea of it, first proposed in 1953. It wasn't seriously planned until 1964, many upset by those plans: set to level Holy Trinity Church (1847), Old City Hall (1889) and the Salvation Army headquarters (1956; Toronto's first, if modest, Modernist office block) -- a price too high for a shopping mall.

In 1967 Eaton's backed off, cancelling the project. For a while: in 1970 they came back with new plans, saving grand history if replacing its more tawdry stand on the west side of Yonge with a classic mall exterior -- a wall windowless and blank.

Cries that it would turn city street to suburban desert won the concession of a few small stores facing Yonge. But what we mostly got on Yonge was, as John Bentley Mays put it, "the styling called, with attractive frankness, Brutalism... Toronto Eaton Centre an unforgettably forceful expression of its final, faded popularity."

Faded (if never much popular) but lasting into the late '90s, when the Eaton Centre marked its 20th birthday with a facelift. Brutal got a mask of New Urbanist PoMo, its exposed bits hidden by a late 20th century imitation of a late 19th century street.

It's nearly all façade, perfect for huge backlit billboards. Out back, Modernism finally fell, the Salvation Army HQ gone for a grand new west entrance to the Eaton Centre, up James Street beside Old City Hall.