|

|

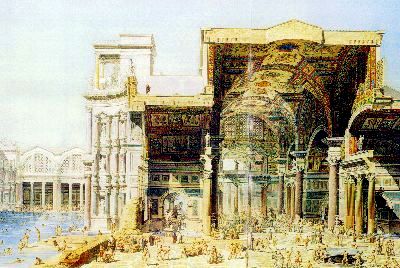

Romans loved water, honoured hygiene, and needed a break from their labours (and banquets). But as de Bonneville says: "what the thermae offered them, above all, was undoubtedly the opportunity for conviviality and spontaneous pleasure."

Pleasure has long tempted loudmouths who like picking quarrels. Men and women had mixed freely at the Baths of Caracalla; "licentiousness" (mixed and otherwise) soon brought laws to suppress it. Few worked. In 320 AD women were barred from the thermae. At the end of that century St John Chrysostom, Patriarch of Constantinople, banned baths altogether. Newly official Christianity would not condone "an interest in the body tainted with sensuality and sin."

Roman baths fell into ruin, stone standing as no more than models for much later architects. Their way of life, their rituals, even their technology, would be lost as living models for some 600 years.

|

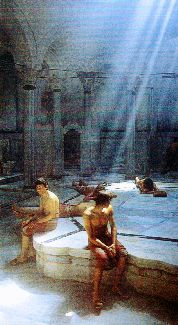

Purification, meditation

A modern hammam, rooted in the Sufi proverb: "Cleanliness is a part of faith."

|

|

Religious fervour ruined the baths in the West -- but would also bring their revival. Bathing and faith had long mixed, and widely. The dry heat of the sweat lodge enveloped First Peoples on spiritual, if personal, quests. Japan had Shinto ritual baths, communal ones as well.

The Jewish mikvah, or mikveh ("concentration of water" in Hebrew), was not for cleansing (one washed before) but ritual purification of women in life's watershed moments. Men waded in just before marriage. The Talmud prohibited Jews from settling in towns without baths. The steamy Turkish hamman was an Islamic site of purification before Friday prayers.

Spain had seen Muslims, Jews, and their baths since the Moorish conquest. The dry heat of Russian baths had spread as far as Germany. But it was the Crusades that showed chilly Christian legions the hammam -- and its more worldly delights.

They found them fit for new times: chivalry had revived interest in the body, in beauty, in seduction. Brave knights need be clean and fit for courtly love. Noble ladies too. Which brings us to that medieval miniature above, done for the Duke of Burgundy circa 1470.

Public baths became part of everyday life across the Medieval West. And not just noble life: the wages of some German workers included Badegeld -- bath money. Taxes on bathhouses funded free baths for the poor. Historian Phillipe Perrot called them places of "an ecstatic promiscuity, in which bodies pampered, plucked and perfumed mingled boldly in the steam and hot water." And beyond.

The church once again attacked forbidden pleasures -- this time, if not for the last time, with a potent ally: disease. Syphilis and bubonic plague gave bathhouses a bad reputation: "shun them, or you will die." Henry VIII ridded England of baths (if not his knights' Order of the Bath, founded by Henry IV ages before). France heard demands, also since familiar, to close houses of prostitution -- including all public baths.

Bathing at home became suspect too, even water itself. For nearly 200 years few washed beyond face and hands, bodies swathed in modesty. And other things.

|

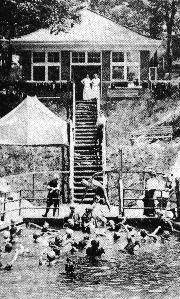

Fun & frolic;

health & hygiene

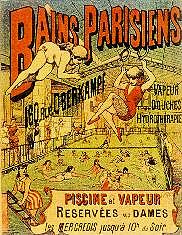

The late 19th century Bains Parisiens, reserved "aux dames" on Wednesdays. Below, kids wait on New York's East Side for swims more sternly on offer -- but they got in frolic anyway.

|

|

Some went on bathing in other ways, taking the waters therapeutic and mineral at Bath, or the spas of Baden Baden. Or taking to the open air. Louis XIV liked to swim the Marne, courtesans in tow. Parisians less noble, and utterly naked, took to the Seine. In 1688, canvas changing rooms rose on its banks -- leading to a craze for swimming baths.

Some became "floating baths." One "elegant two-tiered frigate" had 172 cabins with beds and tubs. The Vigier's staff, male and female, were "most attractive, most neat and tidy and most flirtatious." Some sprang up beyond the river, with pools and baths hygienic, therapeutic, Russian and Turkish.

By 1850 the Gymnase Nautique des Champs Élysées offered billiards, baths, and bedrooms. Its vast main hall was filled by a pool with bridges to a palm covered island, overlooked by two levels of arcade and a sweeping glass arch of roof -- very much a cross between acquacentre and theme park.

The appointments on offer were priced beyond the means of the teeming masses. Few if any had indoor plumbing; all of them, public officials felt, certainly needed a bath. Or at least a good shower.

The Progressive Era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was very much the Age of Public Hygiene. Free, or nearly free, public shower baths first opened in Liverpool and London. But, as Physical Culture noted in 1904, "nowhere in the world is so much being done for the welfare, healthfulness and sanitary conditions of the poorer classes as is being done in the matter of bathing facilities by the New York municipality."

Fourteen floating baths were moored along the East River. Three "splendid interior baths" stood in other parts of the city, four more in the works. From 5 am to 9 pm, overnight in hot weather, "the panting, sweltering crowds from the tenements' poor stand in one continuous line before the bath-houses."

The East Side bath (shown at the left) had 67 showers and ten tubs; in a single year it served 700,000 New Yorkers, a third of them female. Across the city annually, some 5 million people paid their 3 1/2 cents for the pleasures of a public bath.

Pleasure, if surely found, was hardly official intent. Progressive hygiene ever came with a dose of moral reform. There were swimming pools in big New York baths -- even as their superintendent called them "a luxury that the city is not warranted in maintaining at the public expense."

Even worse: "pools and plunges" were, he warned, "unavoidably patronized by all classes and conditions, all nationalities and colors, in all stages of cleanliness and dirt, health and disease." Progressive or not, officials in New York and beyond shared their time's fear of "dirty foreigners" and "racial pollution." Not to mention "immoral acts."

But, even then, messy life found ways to play in the face of stern intent.

|

Skinnydippers

& their later digs

Boys on the Don. Below: Mrs Turner's on Ward's Island (here in 1928, closed); the Sunnyside Bathing Pavilion of 1922 (a water extravaganza underway); & the High Park Mineral Baths.

|

Cook's keyhole

City Lights' 1935 peek inside: "Shades of the Roman public baths with palaver around the pool."

|

|

Toronto city directories have listed baths since at least the 1870s. The category has included quite varied establishments, reflecting much of bathhouse history (short of Caracalla, even if one was called Roman).

There were swimming baths (in their own category by 1940: "Bathing Beaches & Pools"): Mrs Sarah Turner's on Ward's Island from 1900; the City Free Baths east of Parkdale, 1889 to 1911 (likely swimming: it was on the lake shore); the High Park Mineral Baths, listed from 1920 to 1950 (if the photo here is circa 1910). *

By 1922 there was Sunnyside, the famed amusement park at the head of Humber Bay, open until 1955, its Bathing Pavilion splendid accommodation for swimmers long unhoused. Many were kids: the City recorded 92,737 boys and 50,360 girls at Sunnyside Beach from May to October 1906; another 74,000, nearly all boys, at beaches on the Island. And 39,000 on the Don: all boys, if maybe not all naked.

There were baths in The Ward that may well have begun as Jewish ritual mikvah. Henry Nusbaum's Russian bath shows up at 34 Centre Avenue in 1900, Reiman & Schwartz by 1910 next door at 36. By 1925, 34-36 have become the Russian Turkish. The 1937 directory says it offered masseurs, women's hours, and a fee of 30 cents. It was last listed in 1950.

Cook's Turkish Baths had an even longer run. Established in 1874 at 202-204 King West near Simcoe Street, it did not close its doors (if then at 12 Queen East) until 1949. A rare glimpse inside was offered in 1935 by a local magazine called City Lights, taking "A Peek through the Keyhole of a Turkish Bath" -- "with a wink of permission from the manager."

Ten photos (two below) reveal "the mysteries of this fabulous institution" to look not unlike those of a modern gay bath. I have found no evidence it was gay. (We can't even be sure of the Gay Paree Health & Beauty Baths at 551 Bloor Street West, circa 1940-1955.) The writer's nudge & wink does hint he may have been. But Cook's was likely typical of many upscale private men's baths, their clientele refined if few thinking themselves fey, let alone queer.

Harley Thomas's 1876 City Baths at 12 Adelaide West, gone by 1880, was likely not a City-run public bath. The Harrison Baths -- opened at 3 Stephanie Street just north of Queen in 1910, by 1916 moving west to number 15 -- surely was. And still is, at the same address if in digs more modern.

The East End Baths at 188 Sackville Street, in the Cabbagetown of 1920, renamed O'Neill's by 1925, ran as a City public bath until 1950. Another was nearby, on Parliament Street. O'Neill's building fell with the rise of Regent Park.

|

City baths, still here (& not):

O'Neill's in 1916; the Harrison, 2001.

|

The better hotels may have had Turkish baths, as did many in New York and London. But they are not in the city directories. Many small, and clearly transitory, establishments are. There was Robinson's Vapor Bath, at 92 Yonge in 1900, gone by 1905. The High Park Sanitarium was at the same address by 1910 if not there long (also at 92 Gothic Avenue, High Park site of the Mineral Baths). Dr. J. S. Diamond's Turkish was at 223 Queen West in 1876, by 1885 the Turkish & Medical, Dr. Diamond then late, his business gone by 1890.

There were baths Finnish, Mineral, and Mineral Fume. (I've yet to learn what that last one means.) William Watson's Electro Medical shows up in 1890, not there in 1895. Prof. S. Vernoy's Galvanic Baths do too, at 231 Jarvis Street, Turkish on offer as well. By 1895 it's Vernoy's Galvanic, Vapor & Electrical Institution. His Electro Medical Sanatorium is still there in 1900, if not listed under "Baths."

It appeared in the very next category -- convenient for my cursory investigations, if in the moment a surprise: "Batteries."

|

Baths as truly shocking

Toronto Medical & Electro Therapeutic Institute circa 1878, just up Jarvis from Prof Vernoy's later locale. Electricity in the hands of Mrs Jenny Kidd Trout & Miss E Amelia Teft was said to be "a most wonderful curative agent; their success in healing disease, acute & chronic, has been something marvellous."

|

Buzz-makers:

Shocking ads in the May 1903 & March 1921 issues of Physical Culture.

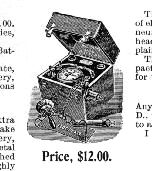

I was baffled at baths literally electrifying. Historian Steven Maynard, who knows those times, told me of a "fascination with the 'medical' potential of electricity, a big branch of quack medicine that tapped broader cultural currents regarding the 'physical decline' of white men of the Empire and preyed on men's insecurities, often over general 'weakness,' but sometimes of a more sexual nature -- impotence, masturbation etc."

Ads for Williams' Electro-Medical Faradic Batteries (above; "Price, $12.00") said that "frequent use of mild currents of electricity will cure rheumatism, neuralgia, lumbago, dyspepsia, headaches and many other complaints." Who knew?

No one, really. Buzz-makers were more careful by the 1920s. Renulife's "Health from Your Light Socket" was, they said, "not a 'Cure All.'" But they clearly saw a wider market, if with gender bias intact. The Milo Bar Bell Company promoted its Gal-Far Battery with: "Nerve Health: It Means to Women glowing cheeks and satiny skin; It Means to Men energy, courage, force -- the will and ability to do."

But, they emphasized: "Gal-Far is not a vibrator."

|

|

Despite their long history of heterosexual liaison, baths now are most often thought of as gay. They are certainly key institutions in gay culture -- if to the chagrin of some gay men seeking more conventional respectability.

There is no comparable space where men and women get together purely for mutual pleasure. If you're thinking brothels, think again. (You shouldn't have to think very hard.) The best comparison is with pubs, central to some cultures -- gay culture, in fact, famously among them.

Gay baths have their roots not in public shower baths (though they surely saw homosexual acts), nor in ritual baths (though the mystery and style of the steamy hammam is oft imitated). They are descendants of those private boites where men could "let down their hair" -- a phrase once common gay code -- and bask together in warmth Moorish wet or Nordic dry, their pleasures unabashedly erotic.

One of Toronto's most famous gay baths, notorious to some, is The Barracks at 56 Widmer Street. The address first appears as a bath in the city directory of 1931, as the Finnish Turkish Baths. It continued as such until 1975, an old (if later) sign still visible out back. Bought then by a group of men, George Hislop among them, it reopened as a bathhouse blatantly gay.

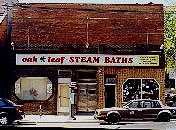

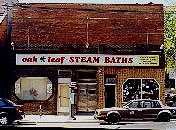

Few local baths have seen such a clear shift in their intended clientele. The Oak Leaf on Bathurst north of Queen -- opened as the Oakview, likely by 1939 -- has long served immigrant men, many Jewish: a piece on it, as an icon, in the December 2001 issue of Toronto Life was titled: "Who gives a schvitz?" Yet gay men have long schvitzed too, even if, as R M Vaughan wrote, the closest thing there "to a gay liberation pink triangle is a Dorito mashed into the carpet."

I have talked to men old enough -- which is to say, not much older than I -- who remember going to the Beverley Steam Baths, opened in 1949 at 137 Beverley Street just north of Dundas, operating until 1974. (The house still stands, shown at the left, as part of a CityHome site. It was nearly torn down in the 1970s for 52 Division's police station. That ended up farther east on Dundas.)

Or to the Modern at 392 Spadina, by 1969 there for 30 years; the Ideal, 471-473 Dundas West, 20 years there by 1969; the Sanitary, at 410-412 Bathurst Street, 1933 to 1968. These men were gay. They had gone to these baths looking for other men. Knowing they would find them; knowing they might have sex with them, maybe right there. But these baths were not, ostensibly, gay baths.

|

Ideal & Sanitary: But gay?

Not so labelled. I knew nothing of these sites until told their names; then I looked them up & paid a visit. The Sanitary (ever said to be a misnomer) has achieved absolute sterility, torn down for a parking lot.

|

|

"Sub rosa"

It's all Greek to me

(or Egyptian)

Latin Confidentially; in secret: literally under the rose, because the rose was the emblem of the Egyptian god Horus, mistakenly regarded by the Greeks & Romans as the god of silence.

-- Funk & Wagnalls --

|

|

This, George Hislop says, is sub rosa knowledge. Old enough to recall not only an 85 cent entry fee at the Oak Leaf but, in his Swansea childhood west of High Park, the Mineral Baths as "The Minnies," George has spent his life learning it. On the gay circuit, limited as it long was, and in the much wider gay world he helped create, teaching it. It is a subtle knowledge, the sort gay men also have of parks that appear, to the everyday wanderer, devoid of erotic life.

Another friend, Duncan McLaren, told me he'd had sex at the Beverley more or less out in the open, most patrons (but one, presumably) ignoring him. George told of benches at the Sanitary wide enough for just one body to lie down on -- but packed close enough for hands to wander.

Not only gay patrons but many without erotic intent, surely staff and owners too, were subtly skilled in the sub rosa. That room, that floor; upstairs, downstairs; at the back, in the steam room, by the snack bar: the rules are different there. Maybe subtly, maybe not. But don't expect to see them posted on view.

Call it "cultural sensitivity." We have to now, when clearly labelled cultures are less apt to mingle than collide. I doubt these men called it anything at all. They didn't have to. It was just civil life: considerate, convivial.

That last word means, at root, simply to live together.

|

Pepperpotty

This odd pillbox at Toronto & Adelaide headed stairs leading to the loo below. An interior shot is dated 1897.

|

|

When "nature calls," what we are called to take is not, most often, a bath. We go looking for the loo. The john, the can, the bog -- a toilet, even if not the full toilette. "Washroom," I gather, is distinctly Canadian, nicely lavatorial. But maybe more apt to urban urgency are comfort station, restroom, public convenience.

There were few in Toronto at the last century's turn. Even toilets in private homes were hardly ubiquitous; some poorer neighbourhoods were entirely without indoor plumbing. Public hygiene called for public lavatories. The City answered the call.

There had been a public potty beneath the corner of Adelaide and Toronto streets since the late 1890s. In 1905 the City Engineer reported it "required a thorough renovation; the ventilation is very poor indeed." It soon got one, its silo removed, a railed open stairway leading down from ground level.

A similar manhole opened at Queen and Spadina in April 1906. It was just for men, as was an earlier lavatory above ground at Yonge and Cottingham, far beyond Bloor. Maybe it was meant to serve the CPR rail line crossing just north: in 1905 it saw just 310 users a day. Twice as many used Adelaide, 733 at Spadina.

As the City Engineer told City Council: "So well pleased are the public with these conveniences that I am convinced that many more should be erected." Or dug. He also said they should make room for women. By 1908, Cottingham did. In 1910, underground lavatories at Queen and Broadview did too. The loos at Parliament Street shown below, built on the same model, likely did too.

|

Crossroad convenience

Covered stairways & vent tower for the underground lav on Parliament at Queen, shown here in 1913.

If not, it was said, "as charming as the vespasians of Paris," this town's public privies were more visible at the time than they'd ever be again. Beyond: the "quite respectable Rupert Hotel."

|

This call for cleanliness in civic space carried a tone all too familiar at the time. As Steven Maynard has said, "there was a constant slippage within the language of the lavatory between issues of public health and issues of morality." Public hygiene meant moral hygiene. As it often has to this day.

In 1911 Toronto's Medical Officer of Health worried that the outhouses and open privy pits of The Ward -- the media's most defamed "slum," crawling with "filthy foreigners" -- were "a danger to public morals, and in fact, an offence against public decency." Even the poor surely know better than to go pooping in the yard. After all: someone might see them. Letters to the big dailies (no doubt "shocked and appalled") demanded the City "remedy the evil."

Not all City lavatories built by then were well placed for the unplumbed poor. More may have been built, but likely not many. Advances in domestic hygiene spelled the decline of public comfort stations, but for those placed to meet the urges of people on the move. Or in big public spaces, like parks.

Still, there is no little irony in moral hygiene making spaces convenient for men inclined to go looking for "vice and immorality."

|

|

Crimes, we are led to believe, are acts clearly defined in law. Police are meant to catch suspects of crime, then hand them over to impartial justice where, if guilty, punishment will fit their crime. In fact, police can create crime. And punish it on their own. Nowhere is this more true than in human acts tagged with a term almost Orwellian: Sex Crime.

Most so-called crimes go on all the time: wife beating; child abuse; environmental pollution (if long not seen as crimes). Sex acts happen every day, no more often at any one time than another. Such acts are named crimes only when police notice them. And when they have reason to notice more often -- to go looking for crimes, to add them up as scary statistics peddled to the media -- we get a "crime wave." (And a boost in police budgets.)

In a 1913 Toronto trial on a charge of "gross indecency," the presiding judge noted "a tremendous increase in this kind of crime." He opined on possible laxity in moral teaching, but also wondered "whether it is the Morality Department that is stirring these things up."

Morality had long been a police concern. In 1886 it got its own branch, under Staff Inspector David Archibald; he would remain Toronto's diligent moral watchdog for nearly three decades. It also got a special weapon: "gross indecency." The term appeared in the Criminal Code of Canada, its first, in 1892. It was not defined. Some parliamentarians had worried, as one said, "that consequences might flow from the phraseology which the honourable gentleman does not contemplate."

That gentleman, Sir John Thompson, framer of the Code, replied: "It is impossible to define the offences any better" -- because they "are so various." And "notorious in another country," appearing here "in one or two places." He named none. Vice was ever seen as a cultural import, usually brought in by immigrants. In fact, its most rabid carrier was mass media scandal.

|

Crime scenes

Allan Gardens; the Queen's Park bandstand (here in 1952) with its loos. Below, box seat for police spectacle: the view from Morality's window at The Parkside Tavern, not closed until 1979.

|

|

From 1913, Toronto was shocked by "sex crime" reportedly on the rise. Steven Maynard, searching local court records from the 1880s to the 1930s, found just eight related cases in 1910. In 1913 there were 29; four years later: 59. By 1922 he found fewer cases than in 1913. The wave, it seems, had passed.

It had been swelled not by more sex, but more avid police attention to sex. They were free to define almost any intimate act they saw as "gross indecency." And they took great pains to make sure they saw it.

At the trial of two men seen by police having sex in the lavatory at Allan Gardens, the cops were asked exactly how it was that they had been able to see them at all. People going at it "in public" usually seek the private cover of a closed cubicle, a hidden corner, a car. And the dark.

The officers happily testified to the extent of their moral diligence. "There is a hole in the wall at the back of the lavatory." From the outside "you can look down into all the compartments ... we have a platform built at the back so that we can." They had a ladder out back too: among the evidence at trial was a picture of both.

They also had "small pocket lamps." In 1919 an officer named Ward got an intimate view of three men at urinals in Queen's Park. From behind. In the dark. "Their elbows were moving." His fellow officer testified: "Ward had his head over their shoulders as the light flashed." Courts heard other tales of police teamwork. "Look at this," one partner urged another, "come over here, wait till you see this."

Sex in spaces where men tried to ensure effective privacy became "public sex." And a crime, created by the police. As Steven Maynard has written, sex between men became "a spectacle for police surveillance." A show. In court, cops often called such intimate acts, forced into sudden display, "a performance."

That Allan Gardens case was in 1922,

that particular moment of scandal already beginning to fade. But sex between men would remain a police spectacle, cops often setting the mise en scene.

In the first issue of The Body Politic, late 1971, Rombus Hube wrote of cruising Philosophers' Walk -- to warn other cruisers of potential entrapment. He'd seen three men there, casually chatting on a well lit ridge, jumped by two others from behind. It was not a mugging. It was a Morality bust.

Activists knew even then that cops eyed the cellar loo at The Parkside Tavern: the spectacle of some forlorn fag dragged up the stairs to a waiting cruiser was one often played out. It took years of protest to close that show, produced with the bar owner's backing. In 1980 The Body Politic would run photos showing the cops' spy hole -- this time with a gay activist perched on a chair taking in the view though Morality's window.

Police surveillance and entrapment were ongoing, mostly low key, picking off the unlucky just a few at a time. But mass moral panic was, when police chose to fan it, ever ready to rise in full flame.

Most later "public" washrooms were in fact privately owned, in bars, restaurants, and malls. But they remained public in the eyes of the Criminal Code. And in the eyes of police forces, in malls often private: eyes ever peering through holes in the wall or into the monitors of hidden security cameras.

Toronto's Gay Courtwatch program reported 610 washroom busts in 1985. And that was just downtown. Suburban malls were busy too. So were sites beyond: in its March 1985 issue The Body Politic reported 183 men busted in six nearby cities, from Orillia to St Catharines, in the previous 19 months.

Fifty eight had been caught by the eyes of police. Or by their bodies. Plainclothes cops not too plain often played sexual prospect. The enticed were entrapped, mere touch became crime -- created, not detected, by police on the scene. The other 125 were trapped by the all-seeing eye of secret video surveilllance.

In many cases, police gave local papers the names and addresses of the accused. Most ran them. Before trial. Only five did not plead guilty, one in St Catharines: a "42 year old salesman, Sunday school teacher and father of two." In January 1985 he was found dead in his car. He had doused his body in gasoline and flicked his lighter. Days before, he had been at the Fairview Mall. Just three hours before, he had been charged with gross indecency.

He missed his trial. He never entered a plea. He was never convicted. But he, and many others, had already been punished. By the police.

|

February 5, 1981

Mass Toronto bath raids lead to massive resistance & a galvanized gay community. Not exactly what the powers that be had in mind.

|

|

I do not know when Toronto's police first eyed baths as potential crime scenes. Unless their attentions led anyone to court, there is likely no public record. Police departments like to keep their files locked up for a very long time.

George Chauncey, in Gay New York, tells of a 1903 raid on the Ariston Baths, police having "discovered that it had served for at least a year (and possibly much longer) as 'the resort of persons for the purpose of sodomy.'" In 1919 there was a raid on the Everard Baths, a placed famed even in European gay capitals.

The sub rosa was above ground by then in New York, police aware of its "pansy" underworld. In Toronto, "fairies" could be found in local tabloids: good citizens knew (or thought they knew) what one looked like. But they were not reported to roost in exclusive "resorts." Searching local records up to 1930, Steven Maynard found no cases rising from busts on baths. George Hislop recalls a police visit to the Sanitary in 1948: stern comments were made, but no arrests.

Don McLeod, researching Lesbian and Gay Liberation in Canada, found nothing on police action against baths before the late '60s, even in the media most likely to have noticed: those "trash" tabloids ever on about gay scandal (hence a source of history otherwise unrecorded).

Don did uncover Toronto's first bath raid of record, on October 27, 1968 at the International Steam Bath, 485 Spadina Avenue, reported in the Toronto Star: 30 men charged, eight arrested, the others issued summonses "for being found- ins at a common bawdy house." It was raided again in August 1973, four charged with gross indecency.

The International had opened in 1968.

And was raided in 1968. There may have been a link, in some minds, with an earlier début: the Roman Sauna Baths at 730 Bay, the first to appeal openly to gay men. The 1966 Yellow Pages listed 26 baths; only the Roman ran an illustrated ad: a man on a sauna bench, wearing just a towel. "Open 24 hours every day. Gentlemen only."

None of the other 25 entries said Men Only; many listed Ladies' Hours. None but the Roman suggested appeal to gay clientele. (The 2002 Yellow Pages has just six entries under "Baths." Four, I know, are gay. Many businesses like those that kept company with the Roman in 1966 are now among the 42 listed under "Spas: Health & Beauty" -- evidence of what "Bath" has come to mean.)

By 1971, the Yellow Pages showed three men lolling in towels: at the 5th Avenue Sauna, "Men Only," 234 Bloor West; the Library, "A Steam Baths for Men," 5 Wellesley West; and the Roman -- now with a male symbol to boot. Within a few years baths would find more targetted media, running big ads in local gay papers. Gay life had grown more visible, more easily found by people hoping to come out (or go in) to a distinct and accessible new world. A growing, booming world.

The police had clearly noticed by 1968. They didn't like what they saw. And they had the power to stop it. Or try to. The Barracks was raided in December 1978, 23 men charged. The Hot Tub Club in October 1979. Forty charged. On February 5, 1981 at 11 pm, the police launched simultaneous raids on four baths, charging 266 men as found- ins at, 20 as keepers of, "a common bawdy house."

Toronto's February 1981 bath raids were the biggest mass arrest in the entire history of Canada. But, instead of scaring gay people back into the closet, as the cops likely expected, those raids sent us out on the streets -- in massive protest. Our sheer numbers surprised even us. Toronto's gay world was galvanized, booming bigger, stronger, ever more visible. It became a political force even police forces were forced to recognize.

Toronto's baths have survived even the moral panic of AIDS. Many US cities shut down bathhouses, seen as cesspits of contagion. Working with AIDS groups born of gay community action, this town's health officials came to see baths as sites of public education. None closed (but for one ransacked beyond repair by police in 1981). In fact, new baths opened. That's a story I tell elsewhere. And that's life -- ever finding ways to go on, despite official intent.

|

Spirit, Mind, Body

And the improvement of all three. Entry portal to one of the world's many branches of the YMCA.

|

Casual intimacies;

erotic anxieties

From holding hands to holding tight: Y baseball team, 1900 & basketballers, 1906; below, a Y-connected Baptist basketball team of 1926.

|

|

-

"Christopher Smith became George Williams' room-mate. The intimate relations, the Christian fellowship of these two young men will never be known, but the power of their lives exerted an influence which is to-day felt throughout the world."

-- Laurence L Doggett, History of the YMCA, 1896

Official intent meeting ironic ends, as history tells us it tends to do, is very much the story of the Young Men's Christian Association. Its history, more complex and interesting than most know, is rich with multiple ironies.

Born of evangelical fervour to save the souls of wayward boys and young men, it is now best known as a gym. Once a temple to the male body, it now sees women working out too. Conceived in stern Christian faith, its unofficial anthem is a gay disco hit. Committed to enlightened sex education, it helped create erotic anxieties that threatened its very foundations.

Begun in London in 1844, the YMCA had among its key aims (as John Donald Gustav- Wrathall, in his 1998 history of the Y, Take the Young Stranger by the Hand, quotes its 1896 historian above): "to satisfy 'the craving of young men for companionship with each other.'" Its founders were J Christopher Smith and his friend George Williams, clerk in a dry goods business. Their effort was born of mutual desire to improve the conditions, mental, physical, and moral, of the many young men working there.

Both were passionate Christians, fired by the agape of brotherly love -- John Addington Symonds's "dear love of comrades," Walt Whitman's "adhesiveness." They were unmarried, devoting their lives to "the work of Christ among young men." Spreading to the US and Canada by 1851, branches of the Y would long be run by "bachelor secretaries," most quite young, married if at all only late in life, and often in pairs loath to be parted.

When apart, their correspondence reveals "an awareness of the embodied nature of male- male affection, a longing for physical proximity, admiration of one another's virility, and a delight in physical touch."

One respected secretary said his fellows "must have intense love for young men as a class, love that will be magnetic." If, technically, chaste. Or, as another Y man put it: "The friend of boys should be a lover of boys -- should have suffered because of boys until he has purged himself without pity of the lustful desires, whether he will or no, to take possession of him...."

By the 1920s, brotherly love was giving the YMCA a serious case of nerves. Secretaries were advised to be "friendly but not familiar," to smile, mix easily, and be ready with "a humorous story." It was, Gustav- Wrathall writes, an image "of friendliness rather than real friendship," the Disney version, its players soon safely married to "sacrificial Y wives."

In the Y's all-male temple of intimate bonding, there was fear of bonds too close. They courted the YWCA, suggesting they get together. Most women suspected a hostile takeover, the YMCA's bid for female "associate members" mere poaching. The YWCA was never as rich or well equipped as its brother club. And behind that glad hand hid the assumption that "associate members" should not ask too much: women should "come to minister, not to be ministered unto."

Besides, some Y men suspected the YWCA of being "subversive of the family," likely harbouring lesbians. In the 1920s, for the first time in its history, the YMCA felt its mission must include the promotion of "healthy heterosexuality."

The haunting spectre was, of course, homosexuality, a concept then named and known more widely than it had been in the heyday of brotherly love. And the Y itself had helped foster that knowledge.

Sex education had begun at the Y by the 1880s, at first in tune with wider efforts to promote "social purity." But, in its programs, the silence and euphemism of moral purists were soon replaced by a more "scientific" approach: "sex hygiene." The Y wanted plain rational talk, to demystify sex. They believed that "more talk about sex would promote intelligent sexual behavior."

The Y was one of the first conduits of "sexology" to audiences beyond the medical elite. Sex researchers had approached their subject as scientists so often do: they dissected it. Acts and affections long seen as random, amorphous, were cut up into neat categories and given distinct names. Those names soon attached not just to acts but their actors: bodies bore sudden labels. Feel a warm glow when you're with your best pal? That's called "Homosexuality." You are "A Homosexual."

Hey man! No way! Committed affections, adolescent pashes, bodies in casual if intimate contact, the easy touch of teammates -- all once innocently shared among men, and among women -- had become suspect. Lines had been drawn. And woe betide those tempted, or even suspected of temptation, to cross them. The YMCA, and the world, tightened up.

|

Christian hunks

& risky ones

"Superbly Developed" in the YMCA's Association Men, Mar 1902 -- complete with measurements. Below: Physical Culture, Mar 1901, In 1907 its publisher was charged with obscenity.

|

|

Working out at the Y goes back to 1869, when a New York branch built its first gym. "Physical work," long part of the mission, was soon part of a wider "physical culture" urging men to take care of their bodies, pay them attention -- and pay attention to other men's bodies as models.

The YMCA, if at first wary of physical "materialism" too worldly, gave Christian permission to men casting eyes on men. Soon they could find "superbly developed" specimens in Association Men, the Y's own magazine.

They bore striking resemblance to men in Bernarr Macfadden's Physical Culture. Dedicated to health, hygiene, and the day's brand of eugenically tinged fitness (its motto: "Weakness a Crime"), it is now seen as a precursor to later "physique" mags that, until the advent of overt gay male porn, discreetly served homophilic interests. Macfadden, once an assistant in physical work at a New York Y, faced obscenity charges in 1907. Association Men had Muscular Christian cover.

Hot bodies in the gym were hardly conducive to control of affections beyond brotherly. In time there were bodies beyond, the halls full of young men taking rooms at the YMCA. It opened dormitories in 1905. In 1920 alone, they saw 10 million temporary residents, twice that in 1940.

The Y carefully chose locations "passed by the largest number of young men in any given time." Sites near rail and bus stations were perfect. Too perfect: these were the classic urban sites of cruising, where men could go unnoticed as they noticed new men and boys in town. Busy transit points were renowned -- Toronto's Union Station notorious -- for sex in public lavatories.

Now the boys could go to the Y. And did -- in droves. Young men sharing rooms did not rouse suspicion. "I often feel quite Roman," wrote Donald Vining, "amid all those naked men." He had worked the entry desk. Gay writer Sam Steward said: "The YMCA is the biggest Christian whorehouse in the world."

There were scandals: big ones in Portland, Oregon in 1912 and Newport, Rhode Island in 1919. But they were few. Christian cover and middle class connections mostly kept out the cops. Steven Maynard's research found just two local Y cases, at the College Street Central branch, now site of Toronto Police headquarters.

The Y's leaders did take note -- if most concerned, says Guastav- Wrathall, that scandal threatened "the very fabric of the organization: loving relationships among men and youth." Many young men began their gay lives in the halls and showers of the YMCA. None will ever forget it.

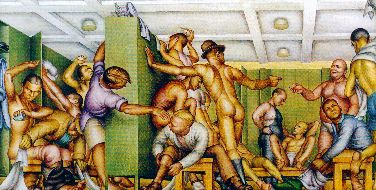

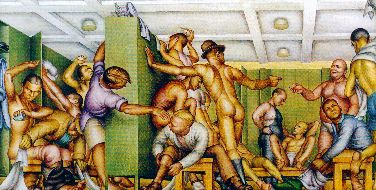

Mixed signals, multiple meanings: "YMCA Locker Room." Paul Cadmus, 1933.

I knew Toronto's Central Y in 1979, three days a week after 5 pm, with friends joining other friends, and many more gay men I knew just to see. Our gang was from The Body Politic. In its August 1979 issue a shot showed some of us running the track, with an article by Michael Lynch: "Young (and old and middle aged too) Men's Cruising Association."

I couldn't get into it, locker rooms not my scene. I suspect they'd be even less so now. Friends tell me that in "gay friendly" gyms, some officially designated "Gay Safe Space," most locker room boys are careful to keep their towels on, relieved to know the shower room now has private stalls. Many don't shower at all.

The Y, and the world, still does "The Tighten Up." Maybe more so now: gay life is more visible than ever. And more tightly defined, more contained: for every brand there's a box with a label -- a box not to be opened just anywhere. The YMCA's pioneering "lovers of boys," however purged and pure, would get tossed in the box marked "pedophile."

I, and my Y friends, helped make that hardening of categories happen. We made many things happen, most liberating. But in opening up the world to "gay" -- a label increasingly fixed, confining, and exclusive -- we may have closed down more fluid options the world once knew. If only in a sense sub rosa.

Now the signs are posted,

rules of eroticism plain to see. No need to bother with subtlety of sense or perception. "Sex" is labelled like any consumer product, on offer in a tempting variety of flavours (or so we're enticed to believe). But in our avid subdivision of the erotic, we may have made the public realm a space where it does not belong.

Laud Humphries in The Tea Room Trade, his study of sex beyond domestication, said that ambiguity -- a multiplicity of signs and signals; a possible range of intent and meaning -- is the essential stuff of cruising.

There may be less cruising now, less easy eroticism in public life, than there was in less clearly labelled spaces, too many lost, of rich, complex, and civil conviviality.

* Dates here represent first and last entries in city directories. But the directories are apparently not definitive: evidence exists of baths not listed, and of baths open before they were listed.

See more on:

Cabbagetown, Regent Park, & the fate of the Rupert Hotel, in Government's house & housing the governed, a tour of Parliament St.

More moral policing of bad boys (& "problem girls"), in

Mad for The Show.

Surveillance, & its penal, military (& lavatory) origins, in

Not at liberty.

George Hislop, The Parkside, baths, raids, & AIDS, in Promiscuous Affections, specifically: 1971, 1972, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1983, & from 1984.

Physique mags without Christian cover, in Beefcake before Blueboy, an article by Alan Miller on the Canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives website.

Shocking technology, in Jeff Behary's Turn of the Century Electrotherapy Museum, a website Steven Maynard alerted me to after this piece was wrapped. (As it says: "Prepare to the shocked!")

Sources (& images) for this page: Might & Taylor (later Might Directories Ltd): City of Toronto directories. William Evart: "New York City's Spendid System of Public Baths," Physical Culture, Sept 1904 (East Side bath). Annual Report of the City Engineer of Toronto, 1906 - 1911. Charles P deVolpi: Toronto: A Pictorial Record, Dev-Sco Publications Ltd, 1965 (Toronto Medical & Electro Therapeutic Institute, from Canadian Illustrated News, Jul 20, 1878). Rombus Hube: "Toronto Civilian Park Patrol," The Body Politic, Nov-Dec 1971. Richard Bébout (ed): The Open Gate: Toronto Union Station, Peter Martin Associates, 1972 (Baths of Caracalla, from William Anderson et al: The Architecture of Ancient Rome, 1927). The Body Politic, No 11, 1974 (cop nips dippers; uncredited). Linda Shapiro: Yesterday's Toronto, 1870 - 1910, Coles Publishing, 1978 (High Park Mineral Baths, from City of Toronto Archives, James Collection). Gerald Hannon: "The view from Morality's window," in "Epitaph for the Parkside," The Body Politic, April 1980 (cops' spy hole). Colleen Kelly: Cabbagetown in Pictures, Toronto Public Library Board Local History Handbook No 4, 1984 (Don dippers & O'Neill's baths, from the City of Toronto Archives, Salmon Collection). Ed Jackson: "St Catharines: indecent exposure," The Body Politic, Mar 1985. Ken Popert: "Indecent Facts," Xtra, Jan 3, 1987. Gary Kinsman: The Regulation of Desire: Sexuality in Canada, Black Rose Books, 1987. George Chauncey: Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, & the Making of the Gay Make World, 1890 - 1940, Basic Books, 1994. Steven Maynard: "Through a Hole in the Lavatory Wall: Homosexual Subcultures, Police Surveillance, & the Dialectics of Discovery, Toronto, 1890 - 1930," Journal of the History of Sexuality, Oct 1994. Donald W McLeod: Lesbian & Gay Liberation in Canada: A Selected Annotated Chronology, 1964 - 1975, ECW Press / Homewood Books, 1996. John Grube: "'No More Shit': The Struggle for Democratic Gay Space in Toronto," in Queers in Space: Communities / Public Places / Sites of Resistance, Gordon Brent Ingram, Anne- Marie Bouthillette & Yolanda Retter (eds), Bay Press, 1997 (Allan Gardens & Queen's Park). Françoise de Bonneville: The Book of the Bath, Rizolli, 1997 (medieval miniature; Baths of Diocletian; hammam; Bains Parisiens). John Donald Gustav- Wrathall: Take the Young Stranger by the Hand: Same- Sex Relations & the YMCA, University of Chicago Press, 1998 (Y teams, 1900 - 1926; men of Association Men, 1902). Toronto Reference Library Picture Collection (Adelaide loo; Parliament loo, from City of Toronto Archives, Public Works Collection; Sunnyside, Toronto Harbour Commission photo, from the Mike Filey Collection; YMCA crest, from Architectural Record, undated). Canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives (Physical Culture; Don skinny dippers, David Adkin papers, from the City of Toronto Archives, James Collection; Turner's; City Lights shots of 1935; Feb 1981 Toronto bath raids, hand tinting by Lynnie Johnston; Cook's ad, from a Right to Privacy Committee fund raising postcard, c 1983). Duncan McLaren (in conversation, Oct 2001). George Hislop (interviewed at the Spa on Maitland, Feb 13, 2002).

Many thanks to Steven Maynard, & to Alan Miller, Don McLeod & Harold Averill of the Canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives, for their help and advice on this chapter.

Go on to:

Mad for "the show"

Working girls, street boys, & moral salvation in Toronto the Good

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/2pconv.htm

Created: Febuary 2002 / Last revised: August 31, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com

|