The New Woman

(& the old)

From domestic servants (here two Finnish girls still maids, c 1915) to working girls out in the world.

|

|

We tend to think of "working women" as a mark of thoroughly modern times. Yet women have always worked, if mostly at home. What marked the many young women who, from the 1880s, flocked to Toronto -- more of them than young men -- was that most hoped to find work beyond home. Any home.

For years, most women worked as servants: girls in unpaid service to their own families; young working class women "moving up" to serve their betters, often for a mere pittance and still under the eye, in loco parentis, of domestic supervision. But Toronto's light industry offered other options: box making; bookbinding; work in bakeries and candy factories; stitching dresses, shoes, hats, corsets.

Their works went to markets all across Canada, Toronto's tentacles reaching out by rail to what was becoming (many griped) its economic hinterland. They worked not in massive factories, like girls from Quebec then tending looms in the mill towns of New England, but in many small businesses. By 1881 more than 1,000 in Toronto employed women, most young.

That year, 20% of Toronto's total workforce was women, more in factories than in the sculleries and boudoirs of upscale ladies. Among manufacturing workers, 30% were female. By 1911, more than 51,000 women worked on shop floors, in stores and offices, in trade, the civil service, in the professions -- nearly five times the number still in domestic service.

They earned, as ever, less than men in comparable jobs. Timothy Eaton -- his vast emporium soon employing more women than any other business in the city -- would explain why: "Girls are more apt when young. They take hold more rapidly at first than boys. But boys in time exert themselves more and aim at being something, to rise higher."

Girls, meant to aim at being mothers, would not stay to rise as "Loyal Eatonians." Timothy paid even a "first class saleswoman" $8 a week; the "average salesman" got $12. In 1921, men earned on average $26.50 a week, women (their average work week longer): $14.23.

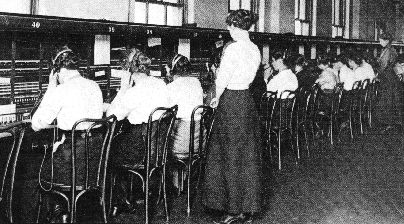

When a royal commission probed working conditions at Bell Telephone, the papers much on about "Hello girls" and their plight, nice people were "shocked to discover that young women who sounded so ladylike on the phone were paid a salary that could barely support a lady's maid."

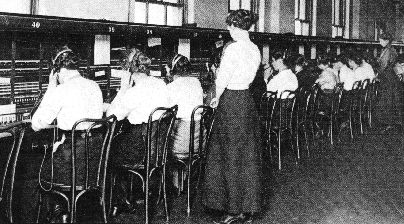

Ma Bell's girls:

Downtown Toronto exchange, c 1909, then at 37 Temperance St.

Matronly supervision, shockingly low pay -- & sometimes work literally shocking.

Bell had first manned its lines with men only, but soon found girls cheaper (and more polite). Operators walked out in 1907, the first such action by women workers in Toronto since the shoemakers' strike of 1882. That royal commission paid little heed to their long hours and low pay, more taken with testimony on other shocks: girls had been knocked cold by zaps from the switchboard.

Now listen here, gentlemen of Ma Bell -- we can't have that. Future motherhood might be at risk. Even if some "Hello girls" had other dreams in mind.

Never had Toronto seen so many young women working, even living, on their own. And so easy to see: pouring into Eaton's, the Christie Brown bakery and Robertson's Chocolates east of Yonge, the Crompton Corset factory; streaming out at shift's end, onto the streets.

Young, single working women were hardly new. But, as Carolyn Strange writes, "their working outside their own families' or masters' homes was unprecedented in Canada." Who's to keep an eye on them? Where, at workday's end, do those streets lead them? No telling what a girl might get up to....

|

Nothing pressing

For the moment -- if ever with an eye to the main chance. Laundry boy taking a break, c 1915.

|

|

As for boys.... Well, everyone knew about boys. If less numerous than girls (Toronto, once a garrison town, now had more female than male inhabitants, 13% more by 1921) they were even more visible. As newspaperman C S Clark (of whom we'll hear more) wrote in 1898: "You can scarcely walk a block without your attention being drawn to one or more of the class called street boys."

-

"The great stand for boys is on the corner of Yonge and King Streets, and at the railway stations, where in the mornings you hear the cry 'Globe, Mail & Empire, World' ... while in the evenings, 'Globe, Mail & Empire, News, Telegram and Star' is rattled off as [fast as] their tongues can utter them. ... the streets are full of little shavers, yelling 'six o'clock Telegram.'"

For every dozen dailies hawked, newsboys made five cents. Between editions many worked as bootblacks: that could bring in a buck a day; shoeshine kits bought new cost a dollar, less at local junk dealers. Clark found them "generally sharp, shrewd lads," if "averse to giving much information with respect to themselves," newsboys "as a rule bright, intelligent little fellows, who would make good and useful men if they got a chance, but some of them are simply stupid."

Many street boys, age 10 to 16, were wanderers, Clark wrote. Some had "no shoes, no coats, and even their shirts are mere apologies for such, yet they are rarely, if ever, sick." Few could afford to be. Some lived at home, some close by in the teeming lanes of The Ward, where boys also worked as runners, rag pickers, street peddlers.

Some tagged along with immigrant dads who'd found jobs building Toronto's new bridges and sewers. Child labour was common -- if increasingly frowned on: kids were cheap competition for those older and desperately looking for work. And, of course, they should be in school. Benevolent employers soon found, nearly as cheap, boys just a bit older. Or, cheaper still, teenage girls.

|

Little shaver; boy builder:

Blaring newsboy, likely hawking the Telegram; kid constructionist catches snapper catching pavers on the Bloor Viaduct, 1918.

|

Boys, like girls, could also be found in factories, behind counters at Eaton's and Simpson's, behind the scenes in shipping rooms, perched on bookkeeping stools, swinging mops, stoking boilers below. The luckiest could be found at hotels, as bellboys -- turned out spiff and shiny clean. And, as C S Clark tells, very much in the know about where to find a good time.

|

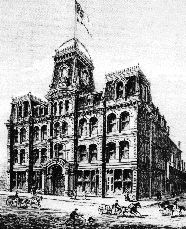

Popular fare

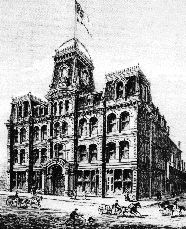

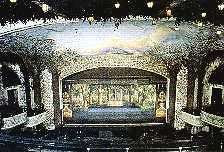

The Grand Opera House, 1874-1920. Even here, in time: vaudeville.

|

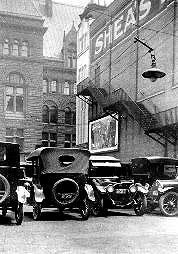

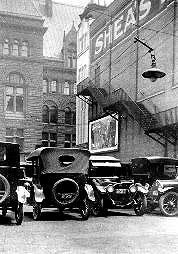

Shea's empire

The Hippodrome, by Old City Hall, 1914-1957 (here c 1920, from the City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, James Collection, Item 1579); below its white enamel façade along Terauley (later Bay) St, & Shea's Victoria, corner of Richmond, 1910-1956.

|

|

Look for popular entertainment in most general histories of Toronto, and you'll be led to St Lawrence Hall (Jenny Lind there in 1851), to the Massey Music Hall of 1889 for the Mendelsshon Choir and later the Toronto Symphony, to the Grand Opera House on the south side of Adelaide between Yonge and Bay.

You're less likely to find the Gayety, the Majestic, the Star Burlesque; the Shea's empire with outposts on Yonge Street and Victoria, its Hippodrome on Terauley near Old City Hall the biggest theatre in Canada. Such names and many more were famously popular among Torontonians in the great and gritty days of vaudeville.

Luc Sante, in Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York, traces vaudeville back to minstrel shows, getting big play just after the US Civil War. The Black Crook at Niblo's Garden on Broadway in 1866, "the greatest hit of the century," five and a half hours long, was "a formless mishmash of fantastic plot elements... a showcase for scores of singers, dancers and musicians... the corps de ballet, scantily clad, for the time, in tights and ballet skirts, was unquestionably the main attraction...."

It prepared the climate, Sante says, "for burlesque, in both of its meanings, as a song and dance farce and as a (highly circumspect) skin show." Gerald Lenton, in The Development and Nature of Vaudeville in Toronto from 1899 to 1915, tells us that those seeking amusement here

-

"could enjoy the daredevils and acrobats, for mystery and intrigue there were magicians, escape artists, mind readers.... Exoticism abounded in the foreign acts and with the fire dancers. And there was plenty of music, songs and comedy, the lifeblood of vaudeville. In other words, there was something for everyone, including the children, who were entertained by animals, puppets, clowns, child performers and animal impersonators. Everything was to be enjoyed and nothing was to be offensive."

Among entrepreneurs who (in the words of George M Cohan) had "an astonishing flair for picking what the public liked" was Michael Shea. Born in St Catharines, Ontario in 1864 if raised in Buffalo, he and younger brother Jeremiah grew up to become "Iron Mike" and Jerry Shea, famed impresarios of vaudeville.

Their empire swelled from a single music hall to 23 theatres in and around Buffalo. By 1899 it including Shea's Theatre at 91 Yonge Street. They had found boomtown: in just 15 years Toronto's population would double. By 1910 they opened Shea's Victoria Street. Shea's Hippodrome -- grand, vast; costing $250,000, seating 2,622 patrons -- opened in April 1914.

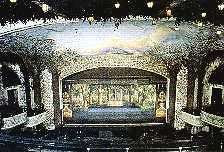

They were not alone. On the block facing 189-191 Yonge running back to Victoria, Marcus Loew built a double decker, based on his American Theatre on 42nd Street in New York. Loew's Yonge Street (later the Elgin), opened December 1913, could hold 2,149; the Winter Garden upstairs, finished two months later, 1,410. "Roof garden" theatres were all the rage, if this one indoors -- with pillars cast as tree trunks, the ceiling a canopy of real beech branches in full leaf.

Around the same time the 1,800 seat Majestic Theatre opened on Adelaide. With Loew's and the two Sheas (Yonge becoming the Strand by 1920), these four palaces could hold 8,000 people, often for two shows a day. The "legitimate" theatres (two west on King: the Princess, burned down in 1915; and The Royal Alexandra, built in 1906 and still there) could seat, just once a night, 3,000.

|

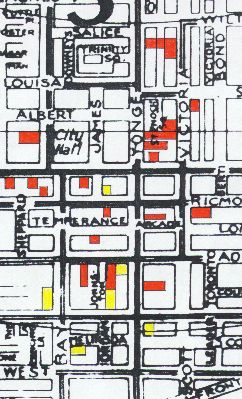

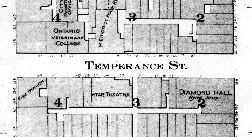

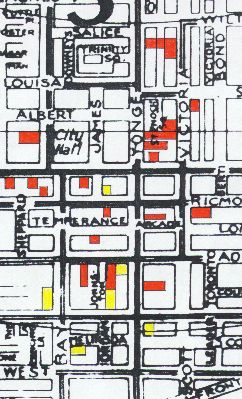

Purveyors of

"Amusement," 1910-20

Downtown's theatres (red):

North of Queen: Shea's Hippodrome; Pantages, 244 Victoria (& fronting Yonge); Massey Hall, 15 Shuter; Loew's (later Elgin) & Winter Garden, 189-191 Yonge; Red Mill, 183, Variety, 8-10 Queen E. South, left to right: Maple Leaf, Globe & Colonial on Queen W; Gayety, 78-84 Richmond W & Allen's at 19-21; L J Applegarth & Son (then His Majesty's), 141 Yonge; Shea's Victoria at Richmond E; Star Burlesque (later Empire), 23 Temperance; Majestic (later Regent), 27 Adelaide; Grand Opera House, on Adelaide to 1920; Shea's Yonge St (at 91; later the Strand).

Toronto's dailies (yellow): World, 40 Richmond; News, Yonge & Adelaide; Mail & Empire, 52-54 King W; Star, 18-20 King W; Telegram, 81 Bay; Globe, 64 Yonge.

|

Patrons of the legit stage paid up to $2 for the privilege of an orchestra seat in "elegant theatrical surroundings." But Loew's and Shea's were just as grand -- with "rich golden tones, ornamental relief work finished in old ivory," handsome murals, vast lobbies glowing with golf leaf and mahogany -- to be enjoyed for 25 cents or less. The Gayety did 10 cent "ladies' matinées." As Gerald Lenton said:

-

"The low-income theatre-goer was therefore no longer a second- class gallery boy forced to use a separate entranceway, but a theatre patron catered to in exactly the same way as any other member of society was catered to, enjoying all the luxuries the beautiful new palaces had to offer."

They didn't have to show up in evening dress, or be restrained in their manners. They were eagerly urged to be part of the show, the auditorium their stage (as Al Jolson knew: he'd stroll a ramp out into the throng). "It was their entertainment," Lenton writes, "they knew how it operated, they created its stars" -- Sophie Tucker, Fannie Brice, strongman Louis Hardt, "Toots Paka and Her Hawaiians."

Their audiences -- men and women, boys and girls, working people momentarily free of their labours -- knew that they themselves were the true kings, and queens, of vaudeville. Even the Grand Opera was on the vaudeville circuit: its manager was Ambrose Small, impressario of "the most carefully booked territory in the world," sending shows across Southern Ontario. The most gripping drama would star Small himself: in 1919 he disappeared without a trace.

Little is left of these palaces of popular entertainment. Shea's Victoria was torn down in 1956; the Hippodrome fell the next year, making way for New City Hall. The Pantages, long derelict, was restored as home to The Phantom of the Opera for a decade; now, like many cultural icons, it bears corporate iconography: The Canon Theatre.

The Winter Garden went dark with the demise of vaudeville, abandoned, nearly forgotten -- and miraculously untouched. Some 40 years later it would be bought and painstakingly restored by the Ontario Heritage Foundation. In 1989 the Elgin and Winter Garden Theatres reopened, glowing time capsules of days gone by, complete with beech leaves still real, if refreshed.

|

Time capsule:

Yonge St entry to the Elgin & Winter Garden Theatres; the upstairs (here in 1975, & today) nearly unchanged since 1914.

|

|

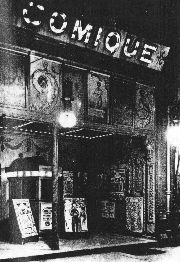

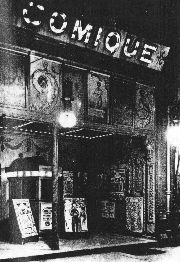

"In the darkness, embossed by silvery images...."

The Comique, 279 Yonge, c 1910; The Big Nickel: 600 seats at 373 Yonge. Below: University Ave plaque marking the birthplace of Gladys Marie Smith.

|

|

Theatres were not the only amusement on offer downtown. In fact, city directories first listed them under their own heading ("including moving picture theatres, opera houses, etc") only in 1918. Before that they'd appeared with other "Places of Amusement" -- 102 on offer in 1917.

The Griffin Amusement Company had six locations in 1910, three downtown later becoming theatres (the Variety, the Lyric north of the Hippodrome, and the Rialto up Yonge Street). Metropolitan Amusement was at 14-16 King East in 1916, Automatic Amusements at 195 Queen West -- likely with the same sort of fare Carolyn Strange noted for Monteford's Museum at Bay and Adelaide: "lectures on wild men from Borneo, displays of living and no longer living curiosities ... wax renderings of arch- criminals or royalty" -- all on one visit, for only 10 cents.

These attractions, too, had American roots: "dime museums," the most famous P T Barnum's American Museum, opened on Broadway in 1842. His "sundry frauds" moved in time to Gilbert's grand hall; it became Madison Square Gardens. Shea's first Toronto location at 91 Yonge Street had once been a dime museum.

If 10-cent oddities had made room for vaudeville, its big houses would in time see stagecraft ushered out, in favour -- at first -- of the small screen. Hand cranked "nickelodeons" offered the first "movies" to mass audiences. By 1907 two million New Yorkers a day took a peek, many at the Automatic Vaudeville with its "scores of machines laid out in rows like a large coin- operated laundry."

The Photodrome at 39 Queen West, circa 1917, may by then have had a big screen, viewed in the dark by patrons packed tight. The Comique at 279 Yonge, 1908 to 1914, billed itself a "movie theatre." The Big Nickel, at 373 Yonge from 1914, had 600 seats (it still stands, if now an "XXX Adult" cinema). And there was surely a silver screen at 380 Queen West, named for its reigning queen, Mary Pickford -- born Gladys Marie Smith, 1893, in The Ward.

Shea's began showing silent films between stage shows; in 1914 at the Grand Opera House, Ambrose Small screened them all summer. In time, the movies were given top billing. But what finally did in vaudeville was the "talkies."

When the movies found a voice -- Al Jolson's voice in The Jazz Singer, a Warner Brothers "Vitaphone" film launched October 6, 1927 in New York -- voices from the stage lost their unique magic. Song, dance, and dialogue now flowed from a flat screen over serried ranks of audience, become more awed spectators than part of the show (at least until that '70s cult spectacle, The Rocky Horror Picture Show).

It was not long afterwards that the Winter Garden went dark. Its projector, set up solely for silent flicks, became no more than a pigeon roost.

Also listed among "Places of Amusement" was Scarboro Beach, opened in 1907 as "a combination open air circus and amusement park" for "youth of both sexes." Most public beaches had long been off limits to girls.

"The City of Illusions" at Scarboro Beach, lit by thousands of electric bulbs, could be seen from the roller coaster at Hanlan's Point -- Toronto Island long the city's most popular (and listed) Place of Amusement. Sunnyside Beach was long busy too: the Griffin Amusement Company had a branch there by 1910, a dozen years before the famed Sunnyside Amusement Park and its Bathing Pavilion opened.

More transitory, if often more packed, were "dance parlours that popped up on the entertainment strips along Yonge Street offering patrons a cheerful, exciting outing, enlivened by music and the energies of bodies in motion."

All these bodies at play -- cavorting in the waves scantily clad; dancing the night away without proper chaperones; snuggled in rows tempting the soul (as New York poet Frank O'Hara would later put it) "that grows in the darkness, embossed by silvery images"; young bodies, boy and girls, together -- well....

|

Indecent attractions

Promo from Bay & Queen (right): "The Half Breed Scout" at the Colonial; the Gayety's "Classy Burlesque."

|

|

For Toronto the Good, all this carrying on was cause for sober concern. It went on in dangerous proximity to the city's most notorious pit of "degenerate" poverty and "foreign contagion," The Ward, north of Queen flanking Terauley, in time connected with (and renamed as) Bay Street.

It was bad enough that the immigrant poor might be drawn to indecent attractions (if few could afford them) -- worse yet that working boys and girls of good Anglo Saxon stock, out for a good time, might have occasion to mix with them.

Towering vigilance:

Queen & Bay, from Old City Hall c 1920 (City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, James Collection, Item 515). Centre: the Temple Building -- Toronto's tallest skyscraper 1895 to 1913 -- temple of the Independent Order of Foresters, its supreme chief ranger a Mohawk, Dr Peter Martin (Oronhyatekha: "burning cloud"), educated at Oxford and an advocate of women's and children's rights. Also, from 1911, home of the Toronto Vigilance Committee, keeping a moral eye on The Ward.

All this right outside City Hall, within sight of city fathers. Should they fail to see (as they were often accused), they need only scan the papers. As the map above shows, the six big dailies had digs in the heart of Toronto's "Amusement" district.

Like intrepid reporters today, bravely trekking yards from their door to tap "the voice of the people" in soundbyte "streeters" (City-TV's stretch of Queen West the most televised streetscape in town), they didn't have far to go to find shock and scandal in the sleazy underbelly of Toronto the Good.

|

Good time girl?

Victim of "white slavery"?

"Bowery gal" from the Daily News, Aug 1902; Soldiers of the Salvation Army rescue a fallen woman from "the social evil," in The War Cry, Mar 1895.

|

|

"The working girl," Carolyn Strange writes, "was an icon of unsettling change." Pondering the impact of rampant commercial enterprise on the city's moral fibre, good citizens ever turned to images of the independent young woman out for a good time. What they saw, as Strange titled her look at the times, was Toronto's Girl Problem: The Perils and Pleasures of the City, 1880-1930.

Few working girls, 80% of them still living at home, saw themselves as "Bowery gals" or "good time girls," even as they escaped shop counters, sewing machines, or factory floors for the freedom of light amusement. But as Carolyn Strange says:

-

"Urban leisure pursuits, such as promenading on commercial strips or frequenting dance halls, were not merely activities that some girls enjoyed: they defined the women who indulged in them. ... The working girl ... was implicated in a paradoxical understanding of urban danger: she signified the perils of the city, both as its chief victim, and as its source."

Working girls were "freighted with meaning" -- springing from "a concerted civic effort to ward off the evils of urban life." Few girls saw such loaded meaning in their own lives, "until they encountered well- meaning philanthropic ladies, self- important industrial commissioners, Morality Department policemen, and earnest settlement house workers."

These forces first saw girls as potential victims, of "white slavery." It had been blared in the news since 1885, rising from reports of child prostitution in London. Girls were ever warned of abductors -- often cast as black, Jewish, or "mysterious Chinamen" -- who would sweep them into the "international traffic in women," their virtue lost to some "American red light district."

In his 1911 tract, The War on the White Slave Trade, Reverend John Shearer, the leading Presbyterian social purist, stated with moral certainty: "The day has passed for proving the existence of a traffic in girls for immoral purposes."

"The pervasiveness of white slavery narratives," Carolyn Strange writes, "lay in simultaneous references to specific cases and archetypal situations." The specifics were few, if easily sensationalized as archetypes horribly pervasive. In fact, "white slavery" as the newspapers sold it was, she discovered, "nowhere conclusively established." Local court records reveal no kidnapping Chinese "slavers."

No matter: in 1910 Shearer had roused moral panic in Toronto with reports that "Social Evil Runs Wild" -- in Winnipeg. Just as Toronto had "Bowery gals" if no Bowery but New York's. "The Social Evil" -- contemporary code for prostitution -- was, of course, everywhere.

Many of those well-meaning ladies were themselves independent women: daughters of good families in decent jobs, intent on doing good works for their less fortunate sisters. But, Carolyn says, "'Business women's crisp white blouses and tailored skirts signalled not only their class position but their adherence to a code of respectability different from that followed by factory girls, whose flashy dress styles made them notorious."

Ladies of the Young Women's Christian Association, reaching Toronto in 1878, ran boarding houses for the "respecable," their efforts "wholly distinct from any work of reclamation" of "fallen women." But, as Mariana Valverde noted in The Age of Light, Water and Soap, the class and age gap between Y women and their charges "led the lady reformers to treat adult working women as girls, as daughters in need of guidance" -- and unceasing moral surveillance.

Some good middle class girls did brave "the slums," their settlement houses "more likely to be found," Mariana writes, "running evening social circles for working girls than giving out loaves of bread." Settlement workers and Y women both were eager to offer morally safe entertainment to girls, competing with -- and often losing to -- "unchaperoned encounters" in dance halls or "terrible scenes of immorality in parks." Or to a bit of fun with boys at the beach.

|

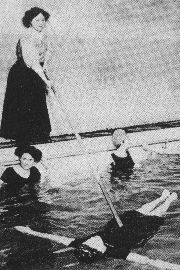

Splashing times:

Girls ponder options at Scarboro Beach, 1907 ("the Shooting Gallery? the Snake Show?"), or find scantily clad & scandalously mixed company at Sunnyside.

|

Only the Salvation Army really got down and dirty. Brought by British immigrants in 1882, led for a time by Evangline Booth, daughter of founder William, finding recruits among the young, single, rootless and poor, the Sally Ann was not above mixing "soup and salvation." Or the gaudy spectacle of brass bands and streetside evangelism -- found vulgar by more restrained reformers. Even as they too were on God's work, most Methodists: their Victoria College in Toronto was the first to train social workers.

But, pushy or polite, social reformers were bent on conversion. If not to Christ, then at least to good "Christian" middle class manners.

|

Good girls?

Residents of the "respectable" Sherbourne House Club, Halloween 1925 -- having some fun with het conventions.

|

|

The "New Woman" could be unnerving even if not working class. Many middle class girls also craved independence: careers in business, education, the civil service, the professions. As college girls looked beyond family and motherhood, beyond marriage (maybe even beyond men), many feared a fall in "good breeding" -- literally, leading to Anglo Saxon decline and "race suicide."

Eugenicists of the day (men and women both, if all middle class or better) bemoaned "good breeding stock" going off the marriage market. But that was hardly the worst of it for "the race." The lower classes, married or not, were going at it like bunnies. Or were thought to be -- "subnormal" women seen as "inordinately fertile," even "excessively heterosexual in character."

Working girls (even if not "boy crazy") had less to fear from collegiate sisters than lady reformers more grandly official. They had powerful male allies: politicians who made laws; police who imposed them. The National Council of Women of Canada, begun in 1894 by Lady Aberdeen, wife of the Governor General, was "less geared to self- help among women and more concerned about getting the ear of the state."

It was, Mariana Valverde writes, "a powerful force in favour of tough enforcement of obscenity laws," and played a key role in agitation over "the dangers that 'feeble minded' women of child bearing age posed to the public." It lobbied for a higher age of consent, special women's and children's courts, and sweeping the "subnormal" off the streets and into asylums.

That wasn't enough for the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (no fans of Lady Aberdeen: she served alcohol at parties and let Catholics into the NCWC). They too pushed for a higher age of consent, and streets swept clean by police. In Ottawa they'd got the curfew bell rung on boys and girls, sending them home at 9 pm.

The NCWC's Committee on the White Slave Trade reported in 1912 that Canadian girls were being abducted at a rate of 1,500 a year. The time for proof was past (if, in fact, it had never come: moral panics need no proof). It was time, they told Parliament, for tough new laws to control "the traffic in women."

In 1913 the Criminal Code was amended to include: concealment in a bawdy house; abducting an immigrant woman to a brothel; exerting control over a woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution. "Victims of procurement" could be any age; the whip was added as punishment for "repeat offenders" -- who, if court records tell true, were largely mythical: in moral politics, symbolism ever holds sway.

Ontario laws -- the Industrial Schools Act, 1877; the Act for Prevention of Cruelty to and better Protection of Children, 1893; the Juvenile Delinquents Act, 1908 -- saw to control of traffic on Toronto's streets.

-

"At nights any time after eight o'clock in the summer, and from seven in the winter these girls pass up and down Yonge street and along Queen west until nearly ten o'clock, when the streets begin to get deserted and to remain upon them would be to make themselves conspicuous. ... A great number of the girls have some regular employment at which they work in the day. Their regular earnings are not large, and this means is pursued to increase them."

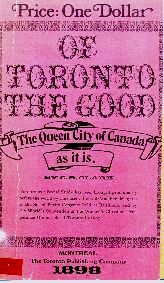

-- C S Clark, Of Toronto the Good, 1898

Christopher St George Clark, reporter in a Montreal office of the Toronto Publishing Company if clearly familiar with its home town, much fretted its various moral quandaries: street boys, thieves, pickpockets, crooks, imposters; gambling halls, licentious lodging houses, even "The Poor of the City."

In his "notorious exposé" of 1898, all that (but the boys) warranted no more than mere paragraphs. He devoted 86 pages to "The Social Evil." His chief culprits were not "white slavers," but working girls themselves: they were, quite simply, out of control. The Morality Department had been closing down "houses of ill repute" -- but to no avail: the "professionally unchaste," he said, had been replaced "by girls who are presumably respectable but who are not really so."

He'd written the attorney general to warn of his pending tirade. "Young men tell me that girls employed by the T. Eaton Co. are many of them prostitutes. That is to say, a young man must first get well acquainted with them, so that they know who he is, and then the results will follow." His evening tour of the town opened with: "Let any girl of eighteen or as young as twelve appear on Yonge street after dark and her reputation is assumed to be light...."

This "scattering of loose women," the ever blurring line between potential victims and likely suspects, had not been lost on the police. Petty crime, vagrancy, "rowdyism" -- the "dangerous class," not dangerous criminals -- had long been their obsession. The Morality Department, founded in 1886, was the first to employ policewomen -- to keep an eye on errant girls.

Even the chief constable, touting the decline in "established houses of prostitution," suspected "competition from women living singly" could be a factor. In fact he and most cops on the beat were, Strange says, "in favour of maintaining an informally regulated red light district segregated from the 'respectable' parts of the city."

It would save decent residents offence, ease the work of regulation -- and line cops' pockets with "protection" payoffs. But Staff Inspector David Archibald, chief of Morality, would not countenance red light enclaves, reportedly saying he "would just as soon license burglars."

The cops, alas, were expected to keep moral order on streets of social confusion. Best, then, to cast a wide net. Laws for control of "delinquents" (undefined in law) and protection of "children" (in some laws now, and likely then, defined as anyone under 18) proved quite convenient. As did those "industrial schools." Hundreds of girls -- from dance halls, dirty shows, debauching beaches -- ended up at Mercer Reformatory on vague morals charges, vagrancy a favourite: all it took was being out without "a good account" of oneself.

Release from Mercer was often conditional on taking a job in domestic service, continued surveillance turned over to the lady of the house. Should her girl "get in trouble" -- with her chauffeur, her Mister, even (and not rarely) her sons -- she'd have the sense to know whom to blame and put out on the street. Or, if benevolent, point to the back street abortionist. Or the baby farm.

|

"A Social Study"

C S Clark's 1898 Of Toronto the Good (here a facsimile edition of 1970): cited in many local histories; its author remains a man of mystery.

|

|

C S Clark's shocking "social study" noted covert ads for abortifacients ("Never fails. Any stage.") in local papers, and pieces claiming "500 babies know not a mother's love" (Strange reports the number of abandoned babies found dead each year "often exceeded thirty"), generally bewailing the world's sad moral state. But C S was no ordinary social purist.

"Coercive laws," he wrote, "do not avail in the suppression of vice." He quoted with glee (which I'm inclined to share) an editorial in Saturday Night attacking the Cigarette Act, which made smoking a crime for anyone under 18:

-

"Enactments should be provided for the imprisonment of boys who insist on sliding down the hill to the detriment of their trousers, and for the making of dreadful examples of girls who let their stockings sag around their ankles."

He, like most police, favoured licensed houses of prostitution -- if, in backing their regulation was careful to state: "I do not wish to be regarded as one of those odious characters, a moral teacher with a mission, a class of people I have always detested." Men like Inspector Archibald, he said, "are not competent to give a reliable opinion on public morality, simply because they know nothing at all about it."

Behind "bad girls," C S said, were errant mothers: "These girls were permitted absolute freedom of action, out all hours of the day or night, free to roam as they chose, while their saintly mothers were doubtless too much occupied with temperance work and women's enfranchisement to give attention to anything so common place as their daughters."

He acknowledged young people as erotic beings, adults having not the "slightest conception" of their "private characters," boys' especially. But girls were even more avid: some out strolling after dark were surely seeking not the glitter of loose cash but "the gratification of pure licentiousness."

When boys got girls in trouble, the girl was surely to blame: "In ninety cases out of a hundred there is no seduction committed at all. It is simply fornication, and in the majority of cases the girl makes the first overture." (Clark did have in common with "white slavery" mongers a fondness for invented statistics.)

"Votes for Women" or calls to close saloons he called "fads," mere publicity stunts. Endless appeals from charitable ladies for support of foreign missions met his scorn:

"East India widows, Chinese and other Asiatic races having Canadian money spent for their benefit and to teach them a religion they do not want, while boys in Canada who steal because they are starving, are filling our prisons." Everything he saw, he was happy to say, "substantiated my idea, previously expressed, that women are largely fools."

As for boys.... Well, C S seems never to have met a boy he didn't like. Or whose story he didn't believe.

|

|

-

"Let any young man of ordinary intelligence and perception make intimate friends with a half dozen boys from sixteen to eighteen years of age, and having won their confidence place no restraints upon their speech. He will learn more in a month than twenty years of theory will teach him."

Our moral correspondent of 1898 clearly lived by his own words: he was ever chatting up boys. Even those he called "men" were rarely past 30. We don't know how old he was at the time -- if clearly suggesting himself "a young man of ordinary intelligence and perception." If a few bootblacks were "averse to giving much information with respect to themselves," many other boys were not.

-

"One lad of eighteen informed me that in five years there had not been a domestic in their house with whom he had not had improper relations. ... One of fifteen stated to me that he had improper relations with a domestic servant who was twice his age, and showed me the vermin on his body she had communicated to him."

A friend he "considered one of the handsomest boys in Toronto," first met at 17, told him of girls at work tempting him to a back room, "and there was hardly one" who'd not had him. "In three years he was a physical wreck."

"A remarkably handsome boy, with a bright healthy color in his cheeks and eyes that shone like stars" told him that while delivering groceries "a young lady the daughter of one of the best known men in the city of Toronto" had said she was alone in the house and "made the proposition that Potiphar's wife made to Joseph" -- a Biblical tale well known, he said, to every bright lad of his acquaintance.

They also knew -- "not a boy in Toronto, I dare say, who does not" -- the precise meaning of a druggist's ad: "Rubber Goods OF ALL KINDS For Sale." He tells of a boy once handing him "a pasteboard coin, silvered over," laughing when he claimed to "see nothing in the possession of such a coin," telling him to tear it open. "I have it in my possession yet."

Some boys, bellboys in particular, apparently knew things that C S Clark suspected even their parents could not have imagined.

-

"If saintly Canadians run away with the idea that there are no sinners of Oscar Wilde's type in Canada, my regard for truth impels me to undeceive them. Consult some of the bell boys of the larger hotels in Canada's leading cities, as I did.... A youth of eighteen once informed me that he had blackmailed one of Canada's esteemed judiciary out of a modest sum of money, by catching him in the act of indecently assaulting one of the bell boys connected with a hotel in that city. ... This is one case only, but they are countless."

Boys of course always told the truth. The whole truth. Of one who had "described minutely" a woman's intimate acts with him, "of such a nature as could have sent her to prison," Clark says: "I believe the narrative because I do not think a boy of seventeen could concoct such a story."

Boys' tales, as Clark retailed them, were ever of seduction -- by girls. Or by older women. Or of "indecent assault" (a term in law, not boys' lingo) by older men. Never anything boyishly incriminating -- if maybe a wink of bravado.

And as C S Clark knew, quoting one Mrs Besant: "A girl has this advantage over a boy, she can sell herself, where a boy cannot, so that where poverty makes a girl a prostitute, it makes a boy a thief."

|

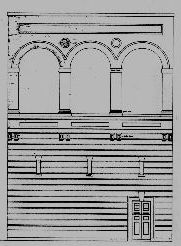

The Star Burlesque

23-27 Temperance St, later the Empire. Sketch based on plans for its 1907 renovation -- perhaps from a rather different incarnation.

|

|

-

"I was coming out of the Star theatre. I met Thomas C. on Temperance Street. I walked to the corner of Temperance and Yonge street. I said it was nice weather. He asked me if I would go to His Majesty's Theatre. I went with him. He got 2 seats at the wall. I was sitting next to him. He drew his hand up my leg. I then went with him to Bowles Lunch. After supper we went to the Hippodrome and after the show I went home."

-- Arnold, age 15,

in written testimony taken by police in the case of Thomas C.

(Archives of Ontario, Crown Attorney Prosecution Case Files,

York County, 1918, case 35)

Court records can only hint at the deeper lives of people suddenly facing the brute force of law. As historian Steven Maynard has said, uncovering the bit above and many more, "they pose formidable interpretive challenges." Whose stories are they, really? And what were they for?

Neil Bartlett, in Who Was That Man? A Present for Mr Oscar Wilde, dug deep in testimony at his notorious 1895 trial -- his crimes most scandalous not for involving boys, but boys of the wrong class: he gave them gifts, favouring silver cigarette cases. His prosecutors wondered, with point, to the jury: "Are they the sort of persons you would expect to find in the company of persons of education?"

-

"But don't get excited. These records aren't meant for you. They are evidence. They aren't meant to inform us of anything: they are there to help form a verdict. They weren't written so that we could identify ourselves, understand the contradictions or pleasures of Wilde's life -- What was it like to be unemployed and in the gay world of 1895? What happened to the boys afterwards? Did they have children? What kind of frock was Taylor wearing? (What I want are details. Details are the only thing of interest.) By putting us in the dock, by making us speak the truth, they silenced us."

Still, like trash tabloids or Clark's tales, they suggest details. Alfred Taylor in his frock was den mother to rent boys -- maybe "something like a gay family" -- in his house on Little College Street. (Maybe we could go find it.) Steven Maynard finds hints too if, a scrupulous historian, he tells us only what he, and we, can know.

Of Arnold and Thomas, we know one was 15, the other a single 26 year old "sausage casing expert." We know that on August 5, 1917, the day after they met, Arnold sought out Thomas again.

-

"I went to his room at 329 Jarvis and we went out and then I went home. Aug 6 I met him again... and we went to the Crown Theatre at Gerrard and Broadview. He opened my pants and handled my privates and I pulled his private person until there was a discharge and he did the same with me. He done this to me 8 times before Aug 31st."

We know they took a trip out west that September, Thomas paying Arnold's way "and fed and clothed me all the time." That they slept together "on Dec 17th ... that was the last time." Four months, 13 days: not a bad run for a "thief."

We know they got caught; we don't know how. We know Arnold gave a statement to the police -- how secured, written by whom ("a discharge"?), or whether he knew its likely use, we know not; there's no evidence he testified at trial. We know that Thomas pleaded not guilty, was convicted anyway, and got one month in jail at hard labour. We don't know what happened to Arnold.

I do know where they slept: not 100 yards from where I do now, 85 years later. I have walked by 329 Jarvis (the site gone to '70s townhouses). I know where they met, and how: "I said it was nice weather." It matters to me that I know. Especially when I find myself at a corner on Yonge Street not far south of Queen.

|

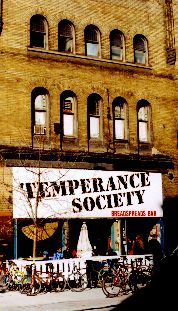

Temperance Hall

21 Temperance St (the New Connexion Methodist Church beyond), the same site -- & maybe same building -- later home to the Star Burlesque.

|

|

Temperance Street is the legacy of Jesse Ketchum, 1782-1867, its name seriously meant. His father had been an alcoholic, his mother dying when he was five, one of 11 children left to the care of foster homes. He became a noted philanthropist (his name on a school in Yorkville, site of a donated park); he paved the town's first sidewalk: with tan bark. From 1812 he owned a tannery southwest of Yonge and what was then Lot Street, now Queen.

In 1830 he moved his business to Buffalo, donating his land to the Presbyterians. Their Knox Church rose where The Bay now stands (and they may still own the land). He also offered land to the temperance movement, for a meeting hall. The effort to "moderate" or entirely suppress alcohol use and its evil effects had begun in Canada by 1827; it gained strength with the import of the US Woman's Christian Temperance Union, the first Canadian branch founded in 1874.

From 1878 "local option" let individual jurisdictions choose to be wet or dry. In an 1898 referendum (Canada's first), full prohibition was backed by a slim majority. It was not binding; Laurier did not act: most in Quebec had voted No. Prohibition did come, all of Canada dry during World War One. But it didn't last: Quebec gave up the effort by 1919 -- US Prohibition launched the next year, lasting to 1933.

Ontario went wet in 1927. Temperance Street did not: Jesse's memory was long honoured by a ban on booze. But his street was not to remain temperate.

|

Jesse Ketchum & his street:

Temperance, above in 1910, Bay left, Yonge right. The Star Theatre is at 23-27, the Methodist Book Room directly north. Below: Bay & Temperance seen from the northwest, 1913, Firehall No 1 (shown on the map above) at the corner -- beneath burlesque promo aimed up Bay; the Star was down the street, off to the left.

|

|

The Star Theatre, its specialty burlesque, made its Temperance Street début in 1907. Plans of that date are marked "renovation": maps show an existing structure on the lot (if with shifting street numbers); its ground plan is the same as Temperance Hall's. Sober restraint, it seems, gave way to giddy excess.

Kids on their own were barred from "moving pictures" and "nickel shows" but, as the Toronto Vigilance Committee warned, "these same minors can freely gain access to a theatre where a burlesque company is giving a risque performance, and there, in a smoke beclouded atmosphere, both hear and see things extremely detrimental."

The Vigilance Committee, founded in 1911, its eagle eye on not only The Ward but "frivolous young girls and boys likely to be easily enticed into wrong doing," came to know the Star well -- as a "training school for immorality." They reported "boys of 8, 10, 12 and 15 years of age were in the gallery, unaccompanied by parents or guardians."

Boys made their own reports, when forced by law. Steven Maynard records 14 year old Reginald S having sex with Ernest O, age 33, in the gallery at the Star in March 1921. Ernest was a ticket taker; Reginald, asked why he'd done it, said simply: "I got in free."

These boys, it seems, were "crazy for 'the show.'" One night in 1922, near the Reo at 214 Queen West, one named Morris approached a man and said: "Let's go up the lane and do some dirty work. I want to make some money to go to the show." He got 50 cents. He had seen the man before, at the Star. Many boys knew they could find such men even at the elegant Winter Garden.

Arnold, Reginald, Morris, and most boys like them did not think of themselves as prostitutes. Steven does note one bold boy of 17, caught in a Yonge Street male brothel, who "presented himself in court as 'a self-confessed pervert.'"

But for most, he says, "sexual relations were rooted in a distinct moral economy in which working- class boys traded sex in exchange for food, shelter, amusement, money, and companionship."

Sometimes their mothers knew -- and, if warily, let it go on. In 1916 one charged that a boarder in her house had been having relations with her son, just 10. He had lived there for two years; she went to the police only after he'd left -- and her son had run away to stay with him. Asked if she had ever beaten her boy, she replied: "I beat him the same as any other child who has to be corrected.... if he deserved it he would get it."

A boy in Ottawa, hired out by his mother to a man's home, ended up in his bed. "My mother told me I had to work," he said. "My mother is poor." Another tried extortion, asking $50 to keep quiet. She got $5, a promisory note for the rest.

Some boys, Clark's knowing if otherwise "innocent" bellboy for one, committed extortion on their own. But his "countless cases" fail to show up in court records: in years of them Steven Maynard found just one explicit mention of blackmail. Boys did sometimes turn in men for what might be called breach of promise: one bellboy, offered a dollar and a job driving trucks, didn't get the job. He went to the cops.

Most boys did not, most charges brought by police, parents, truancy officers, even passers by (one pair were nabbed in a lane off Temperance Street by a civilian rushing out of the Methodist Book Room). Boys 14 or older who had not clearly resisted risked the charge of "accomplice." Even if not, they might have to testify -- not as complainant, but as a witness to crime.

They were often reluctant. "Come on," a prosecutor badgered a boy in 1924, "please tell us how it started and what it was and get through with it -- no use of boggling at it -- come on or we will keep you all day if you don't." Some simply clammed up, whether out of brave loyalty or courtroom terror, we don't know.

Some boys, and girls, were genuinely abused by adults not their parents, bosses, or police. But some too, like Arnold, found connections clearly affectionate, even long lasting. Testimony in that 1924 case revealed a year long relationship of upscale comforts: the older man was an Ottawa doctor.

The details (café suppers, a car, trips to the cottage) would be familiar to any polite gay couple today. But for the fact that one "domestic partner" was 15 years old.

Boys around Temperance Street knew another culture, refined in its own etiquette if less often recognized: street culture. They shared intelligence of certain men, particular places: the theatres of course but also parks, ravines, arcades, lanes often convenient and, quite convenient at the right hour, lunch counters.

Bowles Lunch, where Thomas and Arnold stopped off between His Majesty's and Shea's Hippodrome, a cheap cafeteria open all night, was part of a chain. And well known: boys new in town, whether Toronto or Ottawa, often knew where to find Bowles. The one at Bay and Queen survived to the 1940s, by when it was among other nearby haunts (the Municipal, the Union House) increasingly frequented by gay men. As Steven Maynard says: "In devising their survival strategies, boys gave more than one meaning to 'working the street.'"

Boys were not alone in noting "men of a certain type" (or as a liquor inspector at the Municipal would later put it: "young men with feminine characteristics and possibly sex perverts"). In time they would push even "white slavers" out of the headlines.

|

Moral prod

Good lady keeps girls in line at the YWCA, 21 McGill St, 1908.

|

|

The moral purity of girls and boys both was to be safeguarded by good clean fun. And no little regulation. By 1910 bylaws were in place (police free to enact their own since 1896) to license dance halls, limiting hours and restricting admission by age. Cops had tried to license newsboys -- tagging them "like dogs," Clark complained -- if to no apparent effect beyond padding police hours.

Many social services offered boys recreation, accommodation -- or correction: the Newsboys' Lodging and Industrial Home; the Working Boys' Home; the Catholic St Nicholas Home; the Victoria Industrial School for Boys. Down near the Mercer Reformatory for Women was the final resort for boys a bit older: Central Prison.

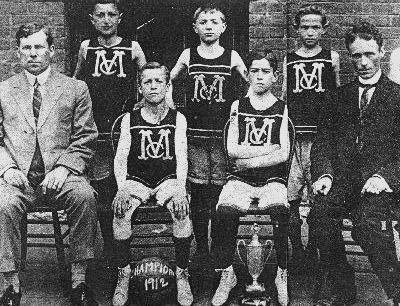

Public school purity:

Muscular Christian (& the other kind?) shepherd boys of the McCaul Street School basketball team, just west of The Ward.

Still, both boys and girls remained mad for "the show." Maybe with more point than their elders might guess: at times they could find their own lives reflected from the stage. Queen of the White Slaves offered "love, intrigue, laughter and tears" -- "a playful approach," Carolyn Strange notes, "to the theme of sexual endangerment." At Shea's in 1910 they could hear a mother's song of hope for daughters at risk:

-

"The city is a wicked place as anyone can see,

And cruel dangers 'round your path may hurl;

So ev'ry week you'd better send your wages back to me

For heaven will protect a working girl."

On the vaudeville stage, the city's perils (and it protectors) became grist for satire. Burlesque, more risqué, risked even political satire. In February 1912 boys at the Star could see "The Darlings of Paris," in which "a sissified policeman was called Archibald." Morality's David -- since 1886 scourge of bawdy houses, tagger of newsboys, lord of the spies on "public degenerates" -- portrayed as:

-

"of the class, or at least pretending to be, who give themselves over to acts of sexual perversion, and known, generally, as 'sissies, 'fairies,' and by other more offensive, but at the same time, more accurately descriptive names."

That screed was from the Toronto Vigilance Committee (talk about "detrimental"): they tried to close "Darlings" down. Maybe they did, if likely not before a few lucky and knowing boys got to go quite mad for one particular show.

C S Clark took boys to the show -- "their criticisms of which," he wrote, "are really worth hearing." If his venue of choice was the Star Burlesque, his avid reportorial ear surely failed to attend more widely.

It is easy to cast Clark as racist, misogynist, a closet pedophile; easy and on some counts correct. If ahistorical, even inaccurate: he liked teenage boys, not children -- though that's a distinction now largely lost in panics over "pedophile rings" and "kiddie porn." We're no more enlightened by the smug assertion that he "must have been gay." Apart from that one scandalous screed, his life is barely recorded.

We're on surer ground with other assessments. Of Toronto the Good was tourism masked as "social study," a rubberneckers' guide to sin and scandal. His codicil -- "The price at which I place the book will keep it out of the hands of all except those who can reason and discuss the theories I advocate" -- was, like "viewer discretion" warnings and bleeps of "dirty" words, meant as a titillating come-on. His letter to the attorney general had been a bid to preempt charges of obscenity.

His investigations were "scientific." "Regard for truth" impelled him to revelation, including the addresses of many brothels: "I was there." (The police were later.) He teased with life's seamy side, duly warning of potential offence -- but he was duty bound to report "the facts." Cast as horribly pervasive Truth: "This is one case only, but they are countless."

He chummed with low life and those who know it, cops knowing best of all. His sources surely had the scoop. He was their mere and blameless messenger.

We can safely apply to C S Clark one sure and telling tag: "journalist."

|

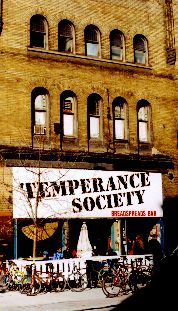

Temperance today

At Yonge, the new Arcade directly opposite (if not the confection seen here); below, a view west to Bay.

|

Working boys

Bike couriers' pit stop: above as Speado; below with a later (& pointed) moniker.

|

|

Jesse Ketchum's street today offers barely a sign of him, its temperate origins, or its later intemperate career. It does, however, have a monument -- on the very site of Temperance Hall and the Star Burlesque -- if from a different era: the "Bonus Era," Toronto's rampant development boom of the greedy 1980s.

It is, as Bob Fulford says in Accidental City, an accidental monument, marking a moment (hardly rare) when, as was said at the time, "people with money, acting in crowds, periodically go off the deep end." It's a massive concrete stump, pierced by portals meant for passage to elevators: six storeys of naked service core -- all that was built of an intended 57 storey office tower.

The Bay Adelaide Centre had been the dream of media mogul Ken Thomson (his HQ on the site of the Temple Building), partnered with Bronfmans, best known for booze (their Seagram's empire booming on bootleg during US Prohibition).

Since the early '70s such corporate hubris had rubbed the wrong way: the City's Official Plan set strict limits on the scale and height of new towers. But official planners had become deal makers: developers could add floors if they offered the city bonuses -- money for low cost housing; preservation of "heritage" buildings (or their faces, leading to the fad for façadomy); maybe a park.

Bay Adelaide shelled out $80 million in bonus bucks. But then the boom went bust: by the late 1980s the project was on hold. A decade later it was revived. Or seemed to be: new promo showed the tower dressed less PoMo. But the site, and its developers, remain oddly quiet.

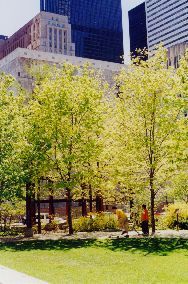

We're left with the stump: "The Magnificent Hulk" as the Star's architecture critic called it; for Fulford "a rough abstract sculpture magnified several hundred times." Its south face has been rented out for advertising. Its north, still raw, looms over the most magnificent accident of all: the bonus baby of Bay Adelaide Park.

|

Bay Adelaide's bonus

"Rough abstract" squatting on the street's south side, where Temperance Hall & the Star once sat; its missing tower (tests for its curtain wall hung on the building beyond) letting the sun shine on boys at play. Left: Cloud Garden behind trees; a bridged span of splashing water; & construction workers' raw materials made public art.

|

The park is a true gem: small and, in its downtown setting, quite rare. Designed by George Baird and Barry Sampson to sit in Bay Adelaide's shadow, it does just fine in sunlight. They had hoped to call up thoughts of both city building and decay: trees rooted not just in the earth but high up, as if on ruins, like a Piranesi etching of Rome. They got, by surprise, the massive presence of a modern urban ruin.

They'd also wanted nature hemmed by, breaking through, artifice. So: a concrete waterfall, a climbing bridge, and a greenhouse -- Cloud Garden, literally in clouds, its tropical collection kept at 100% humidity. The east wall is a monument to, and built by, construction workers: a rusted steel grid of 59 frames, 25 holding designs in copper pipe, aluminum ducts, rough carpentry, raw concrete, steel truss work, electrical conduits, terrazzo, etched glass.

Small signs standing on the park's circular path offer details: on the monument, the park itself, and the area's history. Jesse, his tannery, and temperance get their due. Boys and burlesque do not. Still, I am free there (and I'm there often: the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives is on Temperance just west of Bay) to reflect on lives formally unmarked.

Two lives in particular, both of them boys really. Just there, by the wall fronting that rough stump -- there they were: Arnold, age 15, Thomas 26, finding each other for the very first time, on this odd little street by the Star.

There are still boys on Temperance Street. The park's concrete walks and walls are great for skateboarding, the city's financial heart ever alive with bike couriers. Near the corner of Yonge is a regular pit stop, a hole in the wall with tables out front; when I first saw it the sign said "Speado."

Later it read "Breadspreads Bar." It still does, if as subtext: blazing much bigger, "Temperance Society." Licensed for booze it looks. I went in to check. It is. The man behind the bar smiled when I asked: he knew why I might wonder.

I am ever heartened, in citizenship, to find people who know where they live.

See more on:

The Toronto Arcade -- an early indoor "mall" likely seeing some Temperance St traffic -- in Private property; public life, on a later mall up (& under) the street.

The Mercer Reformatory, Central Prison, & the Asylum, in Not at liberty. For police spying on "public" sex, see Urban amenities; erotic anxieties.

For stagecraft in modern Toronto, & the "little theatre" movement resisting US domination, see Sky Gilbert & Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in Diva Diaries. Ambrose Small can be found, fictionally, in Michael Ondaatje's 1987 novel In the Skin of a Lion.

The Municipal, the Union House, other early Toronto "gay" bars (& a bit of Bowles), in the 1971 chapter of Promiscuous Affections.

Prohibition in Canada (not quite the US "Era") & the class based oddities of later Ontario liquor laws, in Time & Place: Toronto, 1971 (specifically footnotes 1 & 5) on the Canadian Lesbian & Gay Archives website.

For a later work by Steven Maynard -- on another town, if with a Bowles Lunch -- see

"Lowertown Kind of Love: Homo sex in early 20th Century Ottawa".

Sources (& images) for this page: John Ross Robertson: Landmarks of Toronto, "Published from the Toronto Evening Telegram", 1894.

C S Clark: Of Toronto the Good: The Queen City of Canada as it is, Toronto Publishing Co (Montreal), 1898; facsimile edition, Coles, 1970.

Eric Arthur: Toronto: No Mean City, University of Toronto Press, 1964 (Grand Opera House).

Frank O'Hara: "Ave Maria (Mothers of America / let your kids go to the movies!)" in The Collected Poems of Frank O'Hara, Donald Allen (ed), Alfred A Knopf, 1971.

John Kobal: Gotta Sing Gotta Dance: A Pictoral History of Film Musicals, Hamlyn Publishing Group, 1972.

Robert F Harney & Harold Troper: Immigrants: A Portrait of the Urban Experience, 1890 - 1930, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1975 (Finnish maids; suit presser; boy labourer; newsboy; McCaul basketball team).

Linda Shapiro: Yesterday's Toronto, 1870 - 1910, Coles, 1978 (Bell operators; Sunnyside boaters; Scarboro Beach strollers).

Gerald Bartley Bruce Lenton: The Development & Nature of Vaudeville in Toronto, from 1988 to 1915, PhD thesis, University of Toronto, 1983.

Neil Bartlett: Who Was That Man? A Present for Mr Oscar Wilde, Serpent's Tail, 1988.

Hillary Russell: Double Take: The Story of the Elgin & Winter Garden Theatres, Ontario Heritage Foundation / Dundurn Press, 1989 (Shea's Hippodrome façade; Comique; Big Nickel; Winter Garden interior).

Luc Sante: Low Life: Lures & Snares of Old New York,Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1991.

Mariana Valverde: The Age of Light, Water & Soap: Moral Reform in English Canada, 1885 - 1925, McClelland & Stewart, 1991 (Sally Ann rescues prostitute).

Carolyn Strange: Toronto's Girl Problem: The Perils & Pleasures of the City, 1880 - 1930, University of Toronto Press, 1995 (Daily News Bowery gal; Sherbourne House drag, 1925).

Steven Maynard: "Through a Hole in the Lavatory Wall: Homosexual Subcultures, Police Surveillance, & the Dialectics of Discovery, Toronto, 1890 - 1930," Journal of the History of Sexuality, Oct 1994; "'Horrible Temptations': Sex, Men & Working- Class Male Youth in Urban Ontario, 1890 - 1935," in The Canadian Historical Review, Jun 1997; & "'Toronto's Love- Sick Pansy Boys': A Guided Tour of Gay Toronto," paper presented to the annual meeting of the Organization of American Historians, 1999.

Leonard Wise & Allan Gould: Toronto Street Names: An Illustrated Guide to their Origins, Firefly Books, 2000.

Toronto Reference Library, Baldwin Room (Temperance Hall; Bay & Temperance, 1913); Map Collection ("Places of Amusement" background map, 1921); Picture Collection (Jesse Ketchum).

Go on to:

Not at liberty

Jails (& gaols), Central Prison, the Mercer Reformatory, & the Asylum

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/downtown/2pshow.htm

March 2002 / Minor correction: August 4, 2007

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com

|