QUEEN STREET

Moss Park, Trefann, Corktown

Master builders

meet citizen activists

Trefann Court & beyond:

from "urban renewal"

to true civic life

|

Infallible God; fallible guide

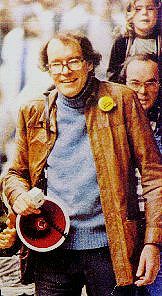

Le Corbusier lays down the law; John Sewell (below, in 1973) helps people learn they can stand up to it.

|

|

Real street; textbook slum

Trefann St, 2001. Below, in a 1970 geography text, captioned: "Toronto, Redevelopment area, Trefann Court, Urban Renewal (Central Mortgage & Housing Corporation photo)."

|

|

Textbook solution

Alexandra Park: 170 Vanauley Walk, seen from Dundas. Walks, no streets: the real Vanauley dead ends off Queen far south. |

-

"The harmonious city must first be planned by experts who understand the science of urbanism. They must work out their plans in total freedom from partisan pressures and special interests; once their plans are formulated, they must be implemented without opposition."

-- Charles Edouard Jeanneret ("Le Corbusier"),

The City of Tomorrow and Its Planning, 1929"I was amazed and shocked when the City didn't listen to the people's arguments, when it said that no matter what the evidence, no matter what the people say about how much they're going to be hurt, the urban renewal plan was going ahead and the area was going to be wiped out.

I had no idea that governments ever did things like that.

But I did have the idea that they should not."-- John Sewell,

Up Against City Hall, 1972

In the summer of 1966 John Sewell, age 25, was a student in law, articling with a big downtown firm. A boy from the Beaches (as he has it), son of a lawyer, his mother having abandoned artistic hopes for the sake of family, he had grown up interested in art, poetry, theology; not politics. His "secure and happy childhood," he would later reflect, "was no introduction to the world most people live in."

He had graduated from Malvern Collegiate, taken the Queen car to the University of Toronto, studied the humanities. His father had said he'd make a good lawyer: "I had no great ambition otherwise, there could be no harm in taking law." He got into the politics of the day, protesting injustices in Alabama, Vietnam. Even dusted up by cops outside the US Consulate, he found the experience "wholly intellectual."

He applied to CUSO, the Canadian Union of Students Overseas ("a precursor to, and not nearly so flamboyant as, the American Peace Corps"), hoping he'd be sent to India, or Africa. He was rejected. Later he'd run into another CUSO reject he'd met at the U of T. Wolfe Erlichman had gone into social work, in 1966 advising residents of a rundown area facing eviction. He told Sewell they could use a student to do some legwork for the law firm they'd hired. Was he interested?

Sewell has said he had gone "from public school to high school to university and into law, and knew nothing of the real world of most people at the beginning or the end." His true education was about to begin.

Trefann Court is a small community, just a few blocks nestled north of Queen between Parliament Street and the Don. In 1966 it was home to 1,350 people, 200 households in fewer houses, nearly all dating from the late 19th century. Four out of ten were owned by their occupants; the rest, generally in poorer condition, were rented to tenants by absentee landlords.

The area had been Irish, then eastern European, a few Macedonians still there. But most residents were Anglo, some French Canadian. A third worked, some locally: there was a rag factory, light industry, auto repairs, a parcel service, retail shops on Queen. Another third lived on pensions, the rest on welfare. "No one," Sewell says, "could be considered in any way a professional."

Their neighbourhood had been under threat since 1957, when a City study marked it among 27 "pockets of blight," designated for urban renewal. Since then, nothing had happened. Literally nothing: the pall of pending expropriation discouraged even minor repairs; properties, and their value, sagged. Why bother with "unslumming" here and there? The wreckers were surely on the way.

They had already wrecked and "renewed" neighbourhoods just north: Cabbagetown gone to Regent Park, North in the '40s, South in the '50s. To the west Moss Park had been wiped out in 1958, vacant four years before its huge towers rose. Some forced out there had come to Trefann, some too from St James Town.

Or from Alexandra Park: nine acres far west near Bathurst and Queen, cleared of houses in 1964 for lower towers and townhouse rows snaking through streetless fields of grass. One resident had written The Globe in 1960:

- "If the 'experts' want to put up one of those cold, sterile, unromantic low- rental housing projects -- which I would hate to have even within sight of my front door -- let them go buy some cheap land on the outskirts of the city and put it there. Just please, please, don't disturb my warm and darling 'slum.'"

Plans to "blow my little system to smithereens," she wrote, "make my blood boil slightly." Just slightly? Sorry darling: the experts know best. And after all: it's for your own good.

The people of Trefann Court were, at first, inclined to bow before experts. Urban renewal was official reality, an ideology unchallenged: in one of their kids' high school texts, Canada: A Regional Geography, they'd see their own back yard portrayed -- a "Redevelopment area" for sure.

The sole issue seemed what kind of deal expropriated tenants might get from the City. It would not likely be good: the displaced were promised "assistance," not full compensation. The City was not bound to offer more than market value for their houses -- that value depressed in an area slated for demolition. Sewell noted that they might offer $10,000 for a house in the renewal zone while just across the street -- across a line the City itself had drawn -- comparable ones went for $15,000.

To help with relocation, the City had sent in Marjaleena Repo-Davis. Seeing that people were going to get hurt, Marjaleena quit the job but stayed in Trefann -- to help its residents resist. Wolfe Erlichman was there, social worker Sarah Spinks too. But, Sewell says, a "well- founded suspicion toward social workers of any kind made their position dubious."

He was "protected by my legal garb" -- seen as a link to those expert lawyers the residents, once organized, had hired. Their job was to get them the best deal. But some residents no longer saw compensation as the issue. He paraphrased their new sense of what was truly at issue.

- "There is no way we're going to win under urban renewal. We're going to lose no matter what happens. If we try to dicker about prices, we're still going to get hurt. What we want is to have urban renewal called off. No expropriation, no demolition, no bargaining about prices; the City should go away and leave us alone."

John Sewell was stunned. "I had thought that everyone considered it a good idea to tear down and get rid of slums. ... I was astonished to find out that people here had something to lose." The big law firm was stunned too; Sewell advised caution: "Those lawyers know what they're doing," he said, "and there's some chance you don't." He pondered quitting. But he didn't: instead he learned that the people of Trefann did know what they were doing.

- "They knew exactly what was going on in their neighbourhood and they had strong views of their own about what should happen. ...they had intelligent ideas about what the city officials and politicians were doing, and they had facts to back up their theories."

"After that initial crisis of conscience," he says, "I chose the role of someone who regards people as the best interpreters of their own interests."

|

Holdouts harassed out

Don Mount Court: no phone, no hydro, no mail -- & a Saturday morning party really bringing down the house.

|

Experts were much afoot just across the river from Trefann, in Don Mount Court -- a neighbourhood much the same, if already falling. Or mostly: a handful of residents had refused to move. No matter: the experts had cunning henchmen.

One holdout, unmoved even by a court order, made the mistake of leaving home at 6:30 on a Saturday morning, heading off to market. Back just 45 minutes later, he found the sheriff, five cops, and a crew of workmen there -- hacking away at his house. By 7:30 the roof was gone. Unhoused, he left.

The area's last resident, an elderly woman, was harder to get rid off. Undaunted by phone, power lines and mail delivery cut, garbage uncollected, streets torn up, Mrs Graham reached her house on catwalks over ankle-deep mud -- built by her son, each morning: every day, workmen tore them up.

In time she had to cut through houses under construction. Sewell found an obscure bylaw stating that the City could not close streets without providing residents other means of access: the only way would have been to tear down houses abuilding. Instead they bought her off with one, listed at $18,000 but offered for two thirds that -- the value of her barricaded home, finally gone.

The people of Trefann found common cause with their neighbours across the river. Some displaced in Don Mount had moved there -- maybe to be displaced again. They might have known, too, of another community then sharing their fate halfway across Canada, in Halifax.

Africville, settled by black people since 1812, had been deemed "land required for the future development of the city." Long standing deeds were ignored, all of $500 offered to the expropriated; all of Africville, its church included, was bulldozed in the dead of night. The land long remained vacant.

But it was done, again, for people's own good. By experts -- in this case touting racial integration and, no doubt, human dignity. Africville's last residents had been hauled away in Halifax city garbage trucks.

|

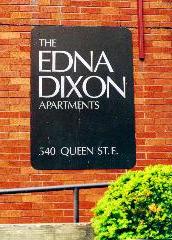

Edna's leads

Factory built with a $350,000 City subsidy; now condos. Below: more affordable housing built since on Queen; old & new at Trefann & Sydenham; back yards no longer suiting "renewal" propaganda.

|

Trefann Court was spared Africville's fate, even the fate of Don Mount. Not by luck, but communal effort -- and lots of hard work. The tale is fully told in John Sewell's 1972 book, Up Against City Hall, source for most my tales above, and a few more below.

Community organizing is not heroic; it has never made anyone rich (at least not in money). John Sewell, along with Wolfe and Sarah, worked in Trefann for $125 a month at first, in time $200. Work included fundraising their own pay -- so they could be there full time, free of other jobs. "We were available sixteen hours a day, seven days a week," Sewell wrote. "We became totally immersed in the area and its struggle." For a while all three lived there, John over a Queen Street storefront.

"Organizing is a simple and yet complicated job to describe," he says. "In essence, it means talking to people, finding out problems, helping with solutions." But, even more, it means helping people help themselves -- in their own ways, not "insisting that they do things your way in return for getting your resources and assistance." I've come to think of it (working mostly with kids) as making space, physical and psychological, where people can move and think and act for themselves.

Edna Dixon made space, her house on Shuter Street Trefann's action central. There she and others worked all day, Edna "an inveterate newspaper clipper" ever gathering evidence, pouring over City documents and reporting what she found in the mimeographed Trefann Court News, kitchen table (if not desktop) publishing.

Among her uncovered facts: the City was offering residents just 75% of the assessed value of their property -- an assessment made by the City itself. And: private firms had got, as enticement to build on the eastern half of the renewal area, a City subsidy of $350,000. Sewell says: "I was astounded that a government would propose such inequities." City tactics would soon disabuse him of any notion that it governed "like some ideal court of justice."

The City did a study ranking Trefann's housing more rundown that it actually was -- so they could get funding from the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation, federal czars of renewal. They tried divide and conquer, buying off landlords (the City itself becoming a slumlord) and local businessmen who'd claim the residents' association didn't really represent the residents.

City officials called Marjaleena's change of heart "immature and unprofessional," Sewell, Spinks and Erlichman "outside agitators," their every word "quoted chapter and verse from Karl Marx." (Sewell says: "I knew nothing of Karl Marx. But I had seen all the evidence.") They asked: "Why do the residents of Trefann need a lawyer to speak for them?" In fact just a law student; developers huddled behind ranks of lawyers dutifully bemoaning the residents' "lack of real understanding and real information."

That's when they could get meetings. At a rowdy one with the Board of Controllers, police turned off the lights. The people of Trefann stood and sang. The Controllers fled to a locked room. The crowd marched out to picket Nathan Phillips Square. Two big papers reported the event -- as a riot at City Hall.

Mayor Phil Givens told them: "If you're going to make an omelette, you have to break eggs." His omelette; their eggs.

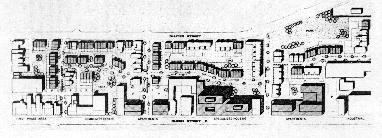

The official plan for Trefann was the hack-Corbusien usual: streets and houses wiped out, no houses even shown, just a swath marked "Public Housing" (for 100 fewer people than currently lived there) with a smudge of "Playground." The real business was on the east, half the site shaded "Industrial."

That plan died in January 1967, the City's governance briefly up in the air while it swallowed the villages of Forest Hill and Swansea. But the threat of renewal was left hanging, various governments playing pass the parcel with Trefann, by then quite a hot potato. The issue of compensation was settled in 1968 by a new, more equitable expropriation act. But by then, to the people of Trefann the "deal" was clearly a dead issue. They had a better idea: a plan of their own, developed with the help of urban designer Howard Cohen.

It was, John Sewell has said, "ordinary in every sense of the word," mystical master planning replaced by local experience and desires. It extended existing streets; it had houses facing those streets, some new, some old and repaired. "The new found its place among the old rather than trying to obliterate or displace it."

Trefann would not be renewed under the dead hand of experts. Instead, it would be revitalized by the hands of its own people. The neighbourhood looks today much as it did before -- if, mixing old and new, better kept (even out back) than when it posed as poster nabe for the ideology of "urban renewal."

City Council approved the residents' plan for Trefann Court (if with the factory already built) in 1972. It was, by then, a very different City Council: for one thing, John Sewell was on it. He had stood for a seat in 1969 -- as a tactic in the Battle of Trefann. If aldermen (or women) wouldn't listen, they could be replaced.

His campaign had cost all of $3,000. The media had ignored him -- but for a few stories on the guy who "Wants to be Poor Folks' Alderman." He ignored them: they were not his constituents. Those he and 130 campaign workers met at their doors, the entire ward canvassed three times. He was wooed by the New Democratic Party but resisted partisan ties. Two candidates could win; the NDP's Karl Jaffary, and Sewell, topped the incumbent -- a cement company flack who had crowed at backing by "friends in the building and construction industry."

Change was in the wind: four other pro-development pols also fell. Elected along with Jaffary and Sewell were historian William Kilbourn, Ryerson urban studies lecturer David Crombie. In 1972 they would win again, Crombie in a three-way race pulling off a surprise: he became Toronto's "Tiny Perfect Mayor."

Architect (later City-TV civic affairs reporter) Colin Vaughan was elected, activist Anne Johnston, fewer boosterish apologists, more swing-vote moderates. On the 1972 "Reform Council" there was, Sewell would say, "wide consensus rejecting the modernist planning ideology." They would curb rampant development, protect neighbourhoods, foster the "liveable city."

Toronto became "The City That Works." It had always, famously, worked -- in a Protestantly Ethical way. Now it would work, if too briefly, as "People City."

John Sewell had hoped that, as an alderman, he would still spend most of his time "on the streets talking to people," organizing. Once inside City Hall -- or as he put it, "in the maw of the Great Grey Clam" -- he would look back on that hope as naïve. In his first meeting with the mayor of 1969, William Dennison went on about how they would make Toronto "the greatest tourist and convention city in North America."

By 1972 the tune had changed, and Sewell had hung in. In 1978 we'd get another three-way race surprise: The next Mayor of Toronto... John Sewell.

|

Inside the

"Great Grey Clam"

|

|

Alderman Sewell at City Hall, standing up against the Spadina Expressway in 1970; in 1978 running to be the next mayor. He was, until 1980. Re-elected to city council the next year, he escaped the clam's maw in 1984. |

|

Urban infill

Sherbourne Lanes: set-back 5 & 6 storey blocks (by Jack Diamond & Barton Myers) sit behind 12 surviving houses (of 13) -- built in every decade from 1840 to 1910. Far right: the oldest, home in 1845 to Enoch Turner -- who gave Toronto its first schoolhouse, still standing in Corktown.

|

The reign of Reform in Toronto (not to be confused with a later Western brand) was, if brief, a wonder. It was not born of electoral victories: they were but one outcome of grassroots action already in bloom, reshaping civic politics.

In 1971 an expressway set to slice into town had been killed by urban activists. "Stop Spadina Save Our City" was a rallying cry -- and a political movement, John Sewell and Jane Jacobs among its key players. South of St James Town they helped people hold off towers set to march from Wellesley down to Carlton.

On Sherbourne Street a grand row of houses due to fall for two 28 storey towers was saved by direct action. The project had been put on hold; the developer ordered wreckers in anyway. One cold dark morning some 80 protesters got there first, among them aldermen Kilbourn and Sewell. And citizen Jane Jacobs.

She had learned of a bylaw by which demolition could go on only behind a barrier. One was up. She said to the crowd: "They can't do this if the hoardings are down. Here, give me a hand." Down went the plywood; the wreckers, in the wrong union to put it back up, went away.

That happend in April 1973, Council by then amenable: the City bought the houses. By 1974 they fronted an "urban infill" site housing more people more affordably (and with more civic sense) than the towers would have. Sherbourne Lanes was the first of many CityHome projects: public, most modestly scaled, set into the existing urban fabric. The days of blockbusting were over.

|

|

CityHome would have a go at whole city blocks: 45 acres below Front Street, south and east of the landmark St Lawrence Market (the site a market since 1803). The area had been, The Liveable City said, "an industrial mess of scrap yards, bus garages, rail spurs and warehouses." It became home to 10,000 people.

|

The Market's new town

Begun 1976, opened June 1979, & growing into the '80s, the St Lawrence Market Neighbourhood is a mix of housing public, private, & co-operative, in buildings big & small, some townhouse rows.

Above, a view from the Market. Left, Crombie Park & the Woodsworth Co-op. Far left, the Market behind one of its new nabe's signs, & a view from the southeast. |

The biggest public housing development to rise in any downtown on the continent, St Lawrence courted failures too familiar. Crombie pushed hard; Sewell slowed him down, making sure community groups were in on the planning. On the planner, they got Jane Jacobs's advice. She suggested Alan Littlewood, a young architect with no degree in urban planning: she'd had her fill of credentialed "experts."

She once overheard him use the word "project." "Don't do that!" she said. "Don't say project. Say neighbourhood, as in community. The way you think about it will determine what you do." Littlewood began to think "infill," even "urban dentistry" -- though the cavity to be filled was untoothed, and vast.

"The building of a modern city neighbourhood from scratch," those Liveable authors say, "has seldom been accomplished successfully." They judged St Lawrence "a decent try" despite a few "mistakes." Among them they thought were structures built high as buffers against busy rail lines and the Gardiner Expressway, "cutting off southern exposure," and the extension of downtown's street grid into the project, "chopping the Neighbourhood up into blocks."

To many, these were marks of its success. Bob Fulford notes that "its edges are blurred," blending into the city around it -- unlike most "projects." There are back yards and lanes, doors facing streets, even a main street. As Sewell has said, it was meant to be "radically traditional," a new neighbourhood that "felt like it had always been there."

But even fans might agree that uniform use, even by varied architects, of Toronto's traditional red brick -- when new nearly persimmon -- can make St Lawrence seem "carved out of one huge orange brick block," with a sad absence of "accident to surprise the eye." Jane Jacobs agrees that it suffers from having been built nearly all at once: nothing has had time to get old. It is not, Fulford says, a perfect Jane Jacobs neighbourhood: that "takes a century or so."

Crombie Park, stretched for blocks between lanes of The Esplanade, turned out less lively than the Tiny Perfect Mayor might have hoped: big open spaces in cities, ever sold as grand public places, can easily end up no place at all.

People living in St Lawrence give it higher marks. They are as mixed in income as their housing is in form: a third of the units rent at full market value, the rest partly or fully subsidized; turnover, usually high in "projects," is low. "This is a village," one said, "we all help run it." It is not Utopia. Nor is Sherbourne: its lanes, lacking the busyness of real city streets, are dotted with signs showing rent-a-cop and German shepherd: "Intelligarde Mobile Response."

A city is more than its buildings: an organism more subtle than its setting, its people ever confounding grand plans. But humane structures shaped by local hands are, at least, a start. Sometimes even when, as one architect said of St Lawrence, they are planned "by middle class Baptists on a crusade."

In this town it's usually Methodists or Presbyterians who get it in the neck. Maybe this critic knew that John Sewell's background is Baptist.

Sewell served only one term as mayor, losing the 1980 election by just 2,000 votes to Art Eggleton, an accountant safely less fierce (now, maybe fittingly, Minister of National Defence). That loss may have been the price Sewell paid for his support of a community even less popular (at the time) than the poor; you can see that story in my memoir, here online.

Re-elected to City Council in 1981, he resigned in 1984, giving up for a time on electoral politics. He did not give up on his city. As chair of the Metro Housing Authority, a commission on planning reform, advisor to the African National Civic Organization, he has gone on fighting, and writing: an urban affairs column in The Globe, later in the alternative weekly Now. He still resists partisan ties, running as an independent in a 1999 provincial election, risking taunts of spoiling the New Democrats' party.

In 1997 he co-founded Citizens for Local Democracy, fighting to keep the old and once radical City of Toronto from being swallowed up by Megacity. He, and we, lost that battle. Megamayor Mel Lastman dreams again of a "world class" convention and tourist mecca, ordinary citizens' more mundane needs met by the mantra of "No new taxes."

It has not worked: services got cut, taxes rose anyway. So did fees for private consultants. Some dare dream of de-amalgamation; just a dream, say the powers that be. "Efficiency" is inevitable -- even as it brings scandal and civic decline.

John Sewell keeps a close eye on Mel and other city pols, lately in his "Citystate" column in another local weekly, eye. He, and we, look back (and forward) to better dreams. As a friend of mine has said (in a song): "Dreams are what we're made of." Even modest ones.

Strolling Trefann I am reminded that they can, sometimes, come true.

See more on:

John Sewell's support for The Body Politic & the embattled gay community, & his later mayoral defeat, in Promiscuous Affections, 1979 & 1980. For Megacity (when a more established gay community let down the side) see Citizenship: In the city & on the streets.

Sources (& images) for this page: George S Tomkins, Theo L Hills & Thomas R Weir: Canada: A Regional Geography. 2nd edition, Gage Educational Publishing Ltd, 1970. John Sewell: Up Against City Hall, James, Lewis & Samuel, 1972; & The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning, University of Toronto Press, 1993 (1972 Trefann plan). Leon Whiteson & S R Gage: The Liveable City: The Architecture and Neighbourhoods of Toronto, Mosaic Press, 1982. Toronto Reference Library Picture Collection (Le Corbusier; John Sewell 1970, 1973, 1978; view of downtown over the St Lawrence neighbourhood).

Go on to:

Private property; public life

The city indoors: The Eaton Centre & "Toronto's Downtown Walkway"

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/mtc/2ptref.htm

December 2001 / Last revised: November 1, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com