|

|

Long lost:

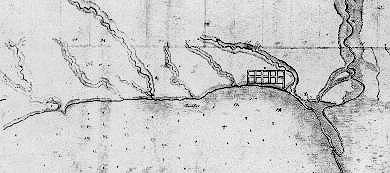

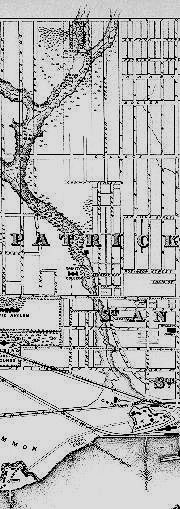

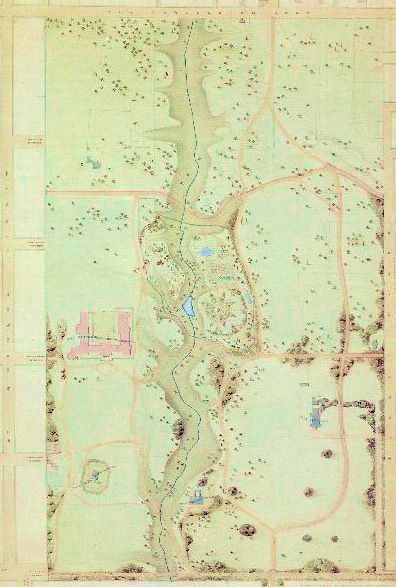

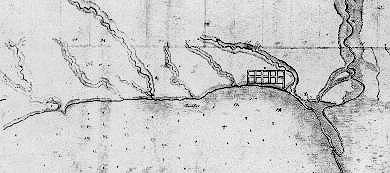

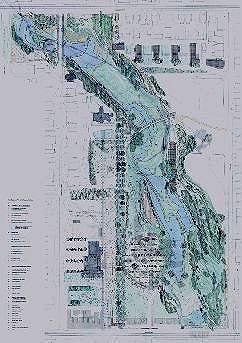

Plan of York, 1818, by Lt George Phillpotts of the Royal Engineers. From the west (left): Garrison Creek; Russell Creek, it mouth near Simcoe St, on maps into the 1870s; &, looping northeast of the Town of York, Fifth Creek, its south branch likely the bottom of Taddle. Alexander Aitkin's 1793 Plan of York Harbour (below) shows others, not there 25 years later. The Don, meandering into the bay on the east, is the only stream here still flowing above ground.

Early maps of this land show many creeks between big rivers east and west. Aitkin had seven (two joined at the mouth) flowing south to the bay in 1793, Phillpotts in 1818 just three. A map of 1827 marks streams, quite small, that they did not. The Humber and Don rivers still run, in part still free; the creeks run too: in sewers. Most are lost even in memory. Fifth Creek (counting east past Garrison, Aitkin's twins likely taken as one) appears in histories of the Town of York, rarely later. Only two do we often recall.

"Garrison Creek," John Bentley Mays wrote in 1994, "can lay fair claim to being Toronto's most famous waterway never seen above ground, at least by anyone I've ever met except Ray Wood." Two years before, "this bright elderly gentleman" had toured Mays over turf "where he played and splashed as a boy."

They began on St Clair West near Oakwood Avenue, more than six kilometres north by northwest of where the creek once watered its lakeside Garrison. There, side streets drop south, turning like the creek did as it carved the banks of ancient Lake Iroquois, lapping what is now Davenport Road.

In 1913, Ray Wood then seven years old, that north reach of Garrison Creek was sent underground in a sewer begun, from the south, in the 1880s. The City's motive was, as ever, Cartesian: streets were meant to run straight. But good burghers, also, never like mess -- and a mess that creek had become.

Victorian developers (and even some later), Mays tells us, "seemed happy enough to build on the soggy trash that had by then clogged whole sections." Houses still line some streets "like rows of crooked teeth," their shallow foundations slowly settling in the muck.

Streets twisting uphill and down are rare in this town, ever imagining itself flat. More can be seen south of College Street where a Garrison tributary long ran. But even downtown, as JB Mays reminds us, "the habitual walker has little difficulty finding and following the rainwater's old paths."

|

Overland water route

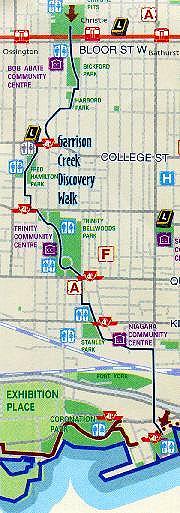

Garrison Creek Discovery Walk, marked at Queen with plaque, steps, & signs. Below, on one of the few bigger signs, the Crawford St bridge, now buried by an embankment seen from steps down to unburied lowlands (also seen atop this page, from atop that bank).

|

|

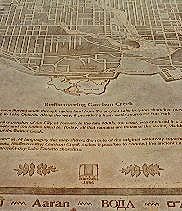

Where Gore Vale Avenue meets Queen West -- the street's subtle dip there marking a valley once deeper -- we can walk Garrison Creek's old path. A big plaque set in the sidewalk, arrayed round it the word "water" in 22 languages, shows that path from the lakefront to Davenport Road.

To the south Walnut Avenue, starting just across Queen, runs straight for a short block and then curves gently southeast, matching the curve of its flanking street, Niagara -- laid out more than 160 years ago along the old creek's east bank.

At its foot rests a matching plaque; at King brass letters on a low wall mark Stanley Park (named for Frederick Arthur, Baron Stanley of Preston, 16th Earl of Derby -- Governor General 1888 to 1893, also recalled in the Garrison's Stanley Barracks, likely Vancouver's Stanley Park and, more famously, hockey's holy grail the Stanley Cup). Letters beside read "Garrison Creek."

At this corner we can climb a few steps flanked by matching signage, the park here Trinity Bellwoods, and head over land where water once flowed in the open. The route is marked by small round signs: "Discovery Walk." Arrows point the way.

|

Up the (downed) Creek

A stream bridged, bricked, buried

Garrison Creek, running free, carved a ravine later seen as a barrier to progress & a smelly health hazard. It was first spanned then cased in brick, much of its vale filled in.

Garrison as creek (below left, 1873) south from Bloor between Ossington (then Dundas) & Bathurst: unbridged north of Queen; some streets shown not yet there.

Garrison as sewer (left) in the works in the 1880s, with workers & it seems, management (City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 2170, Series 376, File 1, Item 15).

Garrison as Discovery Walk (below) in a City guide also noting libraries, community centres, & public loos.

|

Garrison Creek still flows on this route. There is a way to see it, if not by following those arrows. Human guides are required, and special dress: coveralls, rubber gloves, boots, a hardhat. And a lethal gas detector. That tour, once offered to John Bentley Mays, begins at a manhole.

Five metres down Mays found he'd left behind the light, air, and sound of the city for a "ghostly pale glow" (aided by flashlights), stifling humidity, and the gurgle of water "hardly higher than the steel- reinforced toes of our footgear." There were no rats, no evidence of life at all but for "wispy strands of spider webs." But Mays (as is his wont) found he could plumb the sublime.

-

"Many of the artifacts of civil engineering -- bridges, dams, hydro lines, and so on -- forcefully and eloquently express the Modern spirit, without meaning to be anything other than unassuming workaday things. Garrison Sewer is a piece of such engineering, and deserving of special praise, even if its beauty was unintended. The Victorian immigrant masons who laid the bricks of this tubular fabric did so with the care for detail and precise pointing one might expect to find on the façade of a Rosedale mansion...."

That "masterwork" -- two brick layers forming a perfect cylinder eight feet across -- is, he says, "too handsome to ignore, far too dangerous to visit under any but the strictest supervision, too historic to forget, yet destined to be forever unseen under the city's skin of concrete and asphalt." We'll stick, for now, with the arrows.

They lead us up through Trinity Bellwoods Park. At first it feels flat, Crawford Street flanking its west side running level from Queen up to Dundas. But northeast the land dips: a white park hut (at the top of this page) sits nearly on the floor of what was once a ravine. Crawford once crossed a bridge here -- still here, behind and beneath that small vale's west embankment, piled high to bury it.

We're led past parkland to streetscape: Dundas. Just west we head up Roxton Road. Or rather down, into a valley: Harrison Street marks its bottom, as the creek long did. Across it we're walking uphill. An arrow sends us farther up, over a small park on an angle to Shaw Street, leading north to College.

Arrows there point east, back to Crawford. It runs north for a bit, takes a slight arc west, then northeast. At Montrose and Beatrice it meets a public school; a rising walkway into the playground offers one of the few signs actually telling us where we are: "Garrison Creek Ravine."

Coming out on Harbord we face more concrete evidence: a low heavy wall, oddly substantial, flanking the sidewalk across the street. It was once matched on this side. We have approached along level ground, yet we stand well above ground once here -- on the Harbord Street bridge. That wall, its north balustrade, is all we see of it. But the bridge is still here, beneath our feet. Garrison Creek too, both buried.

|

Gone underground:

Exposed north balustrade of the Harbord St bridge. Beside, Bickford Park -- the view from the (non)bridge: built 1905; buried c 1930.

|

Beyond that bridgeless balustrade the ground does drop, if not nearly so far as it once did. Bickford Park rests neat between parallel slopes; big houses perched on Grace Street face across it to the backside of Montrose, garages lining its laneway on the western ridge. Neither rise is natural: the creek and its banks had cut this land on an angle, running southwest.

Skirting east of Bickford Park High School we come to its courtyard, some yards below Bloor's street level; a wide sweep of stairway leads up. Across Bloor, past a narrow stretch of flatland on its north, the land falls again -- sharply, down to the flat bottom of a vast bowl nearly square.

Here, two kilometres north of Queen, some of Garrison's tributaries once joined forces to carve the land we've just walked. The site became a sand quarry, later a City park named Willowvale, still so tagged on some maps. But Parks & Rec has since surrendered to its less picturesque, historically true, and topographically apt moniker: Christie Pits.

|

Surfaces lost

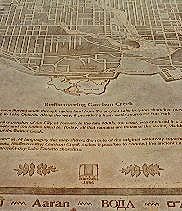

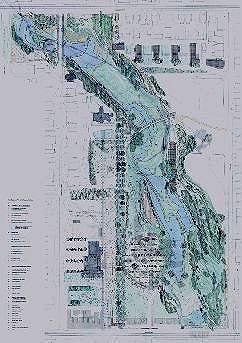

Crawford's odd curve north of College -- & the landscape beneath, shaping it. From Brown + Storey's "Surfaces of Loss," 1996 -- superimposed maps of the city's layers: urban, cultural, & geological.

|

|

James Brown sees a problem in those arrows. Even in signs. He's an architect, knowing that signs often signify the failure of design. Public safety, for instance, demands "Exit" signs. But signs that say "Entrance" mark structures bereft of suggestions we intuit -- not read -- as we move through civic space.

"Don't put up signs," he says. "Make a path." With his partner Kim Storey, their firm Brown + Storey Architects, he had a hand in the matching signage on those walls marking Garrison's parks, Stanley and Trinity Bellwoods. And, perhaps more to his purpose, those plaques showing Garrison Creek's path. In Trinity they recreated a historic path, once linking colleges there: Trinity and St Hilda's.

They have visions for the entire park and beyond -- sweeping, if also deeply subtle: water flowing again on the land, showing us the way; Garrison rediscovered not as a city walk, but a living urban stream.

Civic landscapes

Water shows the way

|

|

|

Running free:

Brown + Storey plans for Trinity Bellwoods, bringing Garrison back above ground as a stream with ponds; Crawford's bridge unburied; a footbridge added; & paths marked by trees, not signs -- or, in the alternate plan for the west walk at the left, by water.

|

That vision runs north on Garrison's route all the way to Christie Pits: the creek running free there and south of Bloor, curving though Bickford Park (fill from its excavation used to restore its west slope's ravine profile, sparing us garage doors), and under the reclaimed Harbord Bridge. Ridges and promontories along the route would recreate its lost glacial landscape.

The intent is not to prettify, but to reconnect city life with the land. Brown + Storey love showing its layers, laid one atop the other: in "Surfaces of Loss," exhibited at the 1996 Venice Biennale, Trinity Bellwoods became contours carved down to its reclaimed creek; streets were shown superimposed on geology below -- most dead straight, ignoring it, a few still minding the sweep of landscape long buried.

Their work is also about a natural function of streams, one we have turned over to technology: the purification of water. The route is rich with ponds, marshes, a wetland reclaimed from the asphalt of that school playground, a parking lot made porous -- rainwater running not off it but deep into the earth's natural aquifer.

|

|

Most often, we send fresh water down sewer grates. We've lately spent millions on a massive trunk sewer to catch the outflow of 12 lines that, in storms, also carry raw sewage overflow -- right to the lake. The big trunk is meant to divert their flow to huge settling tanks; only later does that water see the lake. Then we see that water again -- sucked back from the lake, carefully filtered, chemically purified, all at considerable cost.

Natural watersheds clean water on their own, supporting life along the way and not just our own -- when left alone to do it. We, of course, have not left them alone. But urban infrastructure, rethought, has the potential (as one observer of these plans has said) "to bring delight to necessity."

Brown + Storey's plans for Garrison Creek were on display in the late 1990s at the (then Metropolitan) Toronto Archives, part of an exhibition on the history of this town's water works. It was called "Pipe Dreams." And pipe dreams their plans may have been -- had they sprung from their heads alone. They did not.

The Garrison Creek Community Project, begun in the early 1990s by people living along its route, had as its first goal, JB Mays tells us, "simply to create public awareness of this topographical, ecological, and historical fact... to educate, in other words, and to animate."

Among those involved were ecological activist Whitney Smith, horticulturalist and landscape designer Terry McGlade, James Brown, and Kim Storey. They hoped to raise the creek, at first, in civic consciousness -- convincing the City of Toronto to set up a Garrison Creek Community Advisory Group and (if modestly) to fund its efforts. They won a bylaw requiring various City departments to work together and pool resources for any infrastructure projects along the creek's watershed.

The results are, so far, modest: those distinctive, informative portals at Stanley Park and Trinity Bellwoods; those arrows (less so, if matching Parks & Rec signage on the City's 13 other Discovery Walks); some "traffic calming" streetscape work on Crawford, matched in design with that signed walk at Montrose Public School.

But these modest works rise, at last, from awareness of landscape: its place within the city, and the city's place within it. And from public works, communal efforts, shared visions: Garrison Creek reclaimed not just as history, but as our future.

|

Taddle: tales oft told

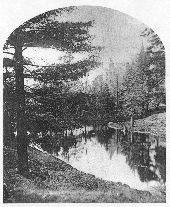

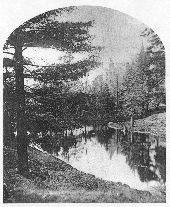

A Notman shot of 1868: University College & its picturesque reflection in McCaul's Pond, a pool of Taddle Creek, shown in the plan at the right, east of the College's pink ground plan.

|

|

In local memory, Taddle Creek has a leg up on Garrison, its tales long told, and often. Taddle ran underfoot of those inclined to celebrate it, sharing its history (and many historians) with University College -- arguably this town's most thoroughly documented building. James Mavor's choice of lookouts atop this page was no mere matter of altitude: his eminences were most nobly elevated, and likely familiar to a man of the writerly class.

Taddle Creek (how named I don't know) rose, like Garrison, from springs north of St Clair Avenue, following a route farther east. Near what is now University Avenue and Elm it cut southeast, crossing Yonge just north of Queen, making "The Meadow" near Jarvis, its marsh long blocking Queen's route east. A map of 1842 shows that run if not its outflow to the bay, likely via Fifth Creek, already buried.

By 1878 maps no longer show that flow southeast, Taddle too underground -- said to trickle through downtown basements, blamed for keeping Eaton's College Street from rising to its intended 40 storeys in 1929 (in legend: in fact it ran nowhere near, that date a more telling impediment to dreams of retail grandeur). But to the north it still ran in the open, cutting land more crucial to its memory.

|

Fabled route:

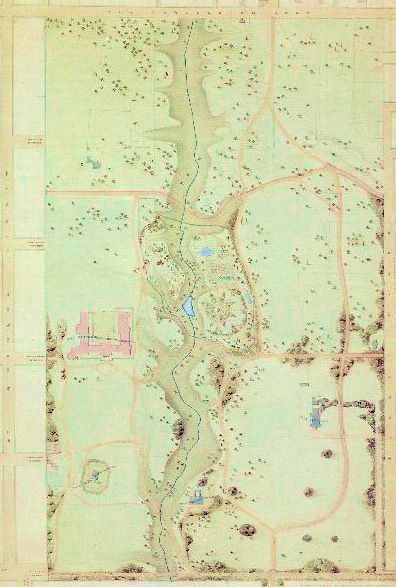

Plan of the University grounds, 1857. Bloor on the north, College south, Surrey Place east, west St George -- then still beyond the bounds. Attributed to William Storm, architect (with Frederic Cumberland) of University College. Southeast across Taddle's meander, cupped by roads now (mostly) Queen's Park Crescent, Ontario's legislature rose in 1892; the small block on the site, here marked "Asylum," was the first & only building of the University's ancestor, King's College, 1842. The U of T still owns this land, Queen's Park out on a 999 year lease.

|

|

Taddle trails

Philosophers' Walk, tracing the creek's valley just south of Bloor, behind the west (& original) façade of the Royal Ontario Museum. Below: Hart House Circle, once (& perhaps future) site of McCaul's Pond.

|

Taddle sanctuary

The gated enclave of Wychwood Park, site of the creek's last run: "Danger / Deep Water / Quicksand."

|

|

Taddle watered the perfect setting for Toronto's new university. The land had been reserved since 1827 for King's College, meant to sit east: grand, balanced, its classic symmetry viewed up the long vista of what is now University Avenue. Only one wing got built: in 1849 the Anglican King's was supplanted by the secular University of Toronto.

Its first building, University College, was designed to later visions: not Classic but Ruskinian Romanesque; not formal vistas but views more subtle, intimate, sylvan -- what Victorians called "The Picturesque." Begun west of Taddle Creek in 1856, it was meant to be approached from across that stream, "seen from the carriage road to the very best advantage" -- obliquely: turrets overlapping, gradually exposed; rising romantic, even mysterious, through a scrim of noble nature.

We now see it dead on, up what historian Douglas Richardson calls "a monumental axis quite foreign to Cumberland & Storm's conception," cut straight north from College Street, 19th century romance sliced by 20th century utility.

Academic Arcadia did prevail for most of Victoria's reign, enhanced in 1859: what was once "a dirty ditch" became "a beautiful feature in the scene." Taddle's flow got a low dam with flood gates: behind it rose a pool 12 feet deep, filling nearly an acre.

McCaul's Pond provided romantic vistas -- and a venue for undergraduate pranks. "Paradisial" in pictures, it was soon "a holding tank for all the sewage discharged into Taddle Creek by residents of Yorkville upstream." In 1883, just before being filled in, the pond and its parent stream were eulogized in The Varsity.

-

Let's soothe thy parting spirits with a Freshman's blood,

And while there's time, imbed him deep in mud,

And sail him tenderly adown thy flood,

Taddle, O, Taddle!

McCaul's Pond may rise again, no doubt its pranks too. The site is now occupied by the Great Hall of Hart House on the north, south by a hill and the old Magnetic Observatory (shown above south of University College, in time moved) -- its dome a perennial Frosh Week canvas.

In the late 1990s the University launched plans to reclaim the lost sylvan landscape of its urban campus. St George Street, once beyond its bounds but long since its main drag, has been rebuilt -- funded by an alumna, designed by Brown + Storey -- more friendly to people, trees, and subtle ceremony than to speeding traffic. It is likely the only downtown artery ever to be narrowed. Other plans are longer term. Should they come to pass, Hart House Circle may again circle water, rather than be circled by cars.

Just north of Bloor Street, Taddle is recalled in a small flatland patch (still rustically signed, as you've seen near the top of this page) up Bedford Road in the Annex, known as one of downtown's nicer neighbourhood. Farther north and west, in one much nicer if less known, we can view Taddle Creek's last remains -- not buried below ground but still on it, running free. More or less.

Wychwood Park hugs a steep wooded slope once the shoreline of Lake Iroquois, rising north of Davenport Road. It dates from the turn of the last century, planned by artist Marmaduke Matthews -- who also gave us Barbara and Alice, Queen's Park, two young ladies by Taddle Creek, painted in 1886.

The park has a gate, west of Bathurst and easy to miss: its sign tells us Wychwood is not your usual park. "Private Grounds," it reads, the gate closed; cars get told to "Enter and Exit through North Gate," off obscure Tyrrel Avenue. On a big stone post anchoring that gate is another sign: "Private Road and Grounds / Please leash and pick up after your dog." Left of that post, the path is ungated: even dogless and unleashed, it seems we are allowed to walk in.

I did: up a steep road through a landscape lush with growth under a vast canopy of trees, some first sprouting more than 250 years ago. It looks as it might have more than 10,000 years ago -- when that glacial lake washed this land now nearly three miles inland -- but for that road, looping up and around, and the houses: few, big, higher up; some nearly lost in the trees.

Many were designed by Eden Smith. He did many in Rosedale, long this town's most famed upscale enclave. Compared with Wychwood -- its green seclusion, its settled richness natural and otherwise, its sense of having been there forever -- Rosedale can feel an anxious suburb.

Nestled in this enclave, loosely circled by that rising road, is a pond. The creek Matthews painted at Queen's Park, at Wychwood he preserved. Near the gate it makes a small bog; just north, dammed, Taddle runs deep. Its banks, steeper as the land rises, are densely forested: ancient oaks frame a patch of sky over water flowing imperceptibly, placid yet filled with life.

Ducks seem unperturbed at my footfall, perhaps feeling secure: the pond is fenced. Human inhabitants higher up, apparently entertaining, ignore me too as I move in trepidation of potential trespass. Posted on a tree is a sign meant to ensure public safety, warning of nature's pitfalls. But like many signs it suggests symbolic, if perhaps unintended, meaning.

|

|

For all its vaunted greenery, Toronto has rarely taxed its civic imagination in pondering the notion of "park." With a few stellar exceptions, quality has been swamped by quantity: civic pols fretting "park deficiency" win votes with the promise of more parks. As John Lorinc wrote in Toronto Life:

-

"The result has been a proliferation over the years of purposeless open spaces -- marginal parkettes adorned with a bit of grass, some sad-sack trees and a few benches upon which no one ever sits."

Toronto spends less per capita on parks than many major cities, per acre, three times less than Chicago. Sports facilities (good for getting votes) get priority: parks like Christie Pits become monocultures, barely used but for baseball or soccer, budgets cut for more casual amenities. Public loos, Lorinc says, "are closed permanently at the mere suggestion of gay sex." People stay away; parks nearly abandoned become no-go zones. Compared to the life offered by the city around them, designer Bruce Mau says, "they're banal."

The term "city park" can seem a contradiction: parks have long been seen as places to escape the city. Frederick Law Olmsted planned Central Park as a refuge from the crowded tenements and roaring streets of Manhattan, its purpose ("almost patronizing," as one Toronto architect has put it) met by its massive scale: half a mile wide, more than two miles long; 840 acres called at once "remarkably beautiful and remarkably artificial." It's not nature. It's "Nature" -- consciously contrived by the city around it.

Reduced to postage stamps, Olmsted vision gives us no more than tatty holes in the urban fabric, not a presence but a civic absence. John Lorinc writes of visions that might knit that fabric together: not "pastoral landscapes divorced from the city, but rather active social ones that connect previously separated communities."

Landscapes animated by civic life beyond Poop & Scoop; by art, theatre, public play. Landscapes populated. "It's pretty simple," Lorinc says. "People like to be where there are other people."

Communal visions are not limited to the bucolic. Another Brown + Storey project, nearly done, sits smack amidst urban glitz: Dundas Square, across Yonge Street from the Eaton Centre. Its bounds are already flanked by tall flashing billboards, gaudy promo, even the world's biggest structure meant solely to support advertising. More will come.

Touted by "World Class" types as Toronto's Times Square (the police, aided by spycams, hope to pacify it Disney style), Dundas Square is not your usual park either. But most big cities have spaces dedicated to sheer glitz, high spectacle, even kitsch; here we will be left in no doubt of the latest brands on offer.

Brown + Storey also show the way beyond corporate hype. Yonge's Strip gets to breathe here, not in a void or even a mall but a space intensely urban: lively, busy -- hence safe. It is not just a destination but a route, a thread in the urban fabric: fountains and a long curved canopy suggest a stroll east. To calmer streets.

Wychwood Park is no model of public amenity. But it is, in a way, a model park: people live there. Many people once lived in (or rather, on) Toronto's most famous park: the Islands, also site of our most famed civic battle over parkland. The issue: whether anyone should live there at all.

For many, the Islands have long been home. By the early 1950s they had some 2,000 residents. More people visited: the main street crossing the outer island to the lake was lined with hotels, rooming houses, dance halls; other hostelries dotted the shore, an amusement park too. In 1956 the new Metropolitan government decided the whole Island chain (but for private yacht clubs) should be public parkland.

That modest strip and most buildings were bulldozed, leaving houses just on the east islands, Algonquin and Ward's. Residents (the Ward family there since the 1830s) were ordered off: their homes were to fall for a miniature golf course. They stood their ground, often dramatically. The battle lasted nearly 40 years, not won for good until 1992.

On Centre Island now there's Centreville, for kids: like most kid attractions it's cute and ersatz. Where the real main drag once ran there are flowers in regimental rows -- an aesthetic once called "squarehead Stalinist." The real life of the Islands lies east, a community (seen as bohemian) still there; at its public school where kids ferried from the city join Island kids, learning natural science; and west at Hanlan's Point, long home to a gay beach and lately one "clothing optional."

Non-Islanders on the Islands have long been amused at a distinctive piece of park signage: "Please Walk ON the Grass." This apparent invitation to anarchy is in fact emblematic of order: paved routes kept clear for park and fire trucks, police cars, tour trams -- the only motor vehicles allowed on islands (so far) unbridged to the mainland.

Most visitors find those signs cute, featured in tourist promo. Few likely ponder the meaning of a place that needs signs to say we're free to take mundane liberties.

Toronto will truly be "A City Within a Park" only when its people know they are free -- together -- to make it a place of civic, and public, pleasure.

See more on:

Downtown Toronto's surviving (if not fully free-flowing) stream, the Don, in Of time & the river. Taddle Creek's historic neighbour, the University of Toronto, in Dreams of grandeur; Garrison Creek's in York's fort; Toronto's reserve.

A small Toronto park shaped by urban imagination (& civic serendipity), Bay Adelaide, near the end of Mad for "the show".

Sources (& images) for this page:

James Mavor: My Windows on the Street of the World, J M Dent & Sons, 1923 (quoted in Christopher Armstrong & H V Nelles: The Revenge of the Methodist Bicycle Company: Sunday Streetcars and Municipal Reform in Toronto, 1886 - 1897, Peter Martin Associates, 1977).

G P deT Glazebrook: The Story of Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1971 (Garrison Creek map, from the Toronto City Directory, 1873).

Nathan Silver: Lost New York, Schocken Books, 1971.

Students of the Toronto Island Public School: A History of the Toronto Islands, Coach House Press, 1972.

Douglas Richardson: A Not Unsightly Building: University College and its History, Mosaic Press, 1990 (Plan of the University grounds, 1857; McCaul's Pond, 1868).

Carl Benn: Historic Fort York, 1973 - 1993, Natural Heritage / Natural History Inc, 1993 (Plan of York 1818).

Beth Kapusta: "Infrastructure and Parks: The Garrison Creek Community Project," The Canadian Architect, Jun 1994 (Harbord bridge, 1905).

John Bentley Mays: "Binding and Loosing the Waters," in Emerald City: Toronto Visited, Viking, 1994 (Manhole, 1924).

Anne Michaels: Fugitive Pieces, McClelland & Stewart, 1996.

City of Toronto: "Toronto Parks and Trails" (undated brochure, c 2000; full map of city parks, & the Garrison Creek Discovery Walk).

John Lorinc: "Greened acres," Toronto Life, Jul 2002. Toronto Life 2002 Real Estate Guide, Feb 2002.

Toronto Reference Library, Map Collection (Plan of York Harbour 1793).

Brown + Storey Architects: "Surfaces of Loss," VI International Exposition of Architecture at the Venice Biennale, 1996 (Crawford St contours); & "Trinity Bellwoods Park Regeneration" (plans). Courtesy of James Brown, with thanks to him for a conversation as well, Jun 23, 2002.

Go on to: EMPIRE

York's fort; Toronto's reserve

The Garrison: birthing, briefly losing, & long shaping a very British town

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/libtrin/2pcreek.htm

July 2002 / Last revised: November 14, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com

|