|

Promiscuous Affections A Life in The Bar, 1969-2000

1996-1999:

|

A mari usque ad mare: Coat of arms of Canada, at Sunnybrook, born a veterans' hospital. "His dominion shall be from sea unto sea; from the river unto the ends of the earth." That last apt bit fell away, as has "Dominion," chosen over "Kingdom" to appease the US; let fade in attempted appeasement of Quebec. |

|

Built to last

|

Enter the city like a king; have it ring the hours for you; drink from the fountains of Versailles.

Public amenity, once a source of pride, is now impoverished, scorned: governments are broke; corporations are "efficient."

Citizenship

In the world & at work

A while ago I told a friend, who knew I was writing on life in The Bar, that I planned to call the penultimate chapter of this work "Citizenship." He asked why; a reasonable question.

But for me that's what this whole story has been about: the claiming of full citizenship by a people once denied it in the wider world, even in daily life. There is, to my mind, even a citizenship of The Bar.

I don't mean the term merely in the state sense, though there is that sense too. I am among those lucky people, many in number if few overall, who freely chose their citizenship. On April 30, 1975, I became a Canadian by an act of will, eagerly -- just as eager to be no longer an American.

It's a choice I've not regretted for a moment, not even as some Canadians line up for green cards, ticket to supposed greener pastures to the south. Lower taxes we're told, if on close scrutiny it's not true -- unless you're rich enough not to fret what private health care may cost.

***

I have always been proud to pay taxes.

The state taps my meagre income for just a few hundred dollars a year; in fact the state provides most of that income -- a federal disability pension; a provincial plan covering what otherwise would be, as they say, "catastrophic" drug costs. I'm very glad for both.

But I was just as glad when less supported by the social safety net than helping support it myself. Every time a fire truck roars by, or an ambulance -- especially the air ambulance, a helipcopter coming in low over the city to land atop the Hospital for Sick Children -- I think: this is what matters to us; we take care of each other, that care a public trust.

I feel that walking between the towering 75 ton pillars of Union Station -- "a blessed sense of civic excess," Douglas Richardson said in 1972, quoting architectural historian Vincent Scully on the Beaux Arts.

Or gazing up the finely carved sandstone cliffs of Old City Hall, waiting for its clock to strike the hour. Even being forced to a trial there hasn't put me off, that sound still my favourite in the city.

Built to last, both of them and much else, as a public trust.

Perhaps especially, I feel it touring the huge lakefront filtration plant in the city's east end -- in 1988 as a gallery, an exhibition of "WaterWorks" arrayed amidst its vast pools and roaring turbines. A nice idea that -- but the art paled against the building, a veritable Versailles of public works (if done in Art Deco), a monument to pride in a grand endeavour both vital and mundane: providing a city with clean water.

(In the small town of Walkerton, Ontario in May 2000, we'd see how vital the mundane could be: six people were killed there, many more made seriously ill, by e-coli in their tap water. The Tories had slashed public spending on utility inspectors.)

The commissioner responsible for that vast water plant (it bears his name) was also the force behind the 1915 Prince Edward Viaduct, black steel arches spanning the vast Don Valley, silver subway trains gliding through, planned for 50 years before they arrived.

I love what we've given each other in the name of public good.

***

The "public good" is not very popular now. Not even governments much defend the role of government in the face of corporate "efficiency."

The "market" is God now, its ideology of the purest kind: so pervasive it's invisible; not a human creation but an inescapable force of nature. "Efficiency," it's been said, is a highly ideological term, yet we see it as neutral, mere "common sense."

Tax cuts are all the rage, even the left conceding to the cry (or supposed cry, the loudest calls coming from corporate media). We are rarely called "citizens" now. We are "taxpayers," "customers," "consumers" (all requiring money). Governments boast they'll "put your money back in your own pocket" -- so you can consume even more.

That line is, in truth, one of the greatest cons of modern history: our collective pocket will be picked to line the pockets of a few. Very few.

And very rich: too rich to consume much more than they already have but for luxuries with little impact on the overall economy; too smart to "invest" in anything but the currency market, where money generates nothing but money, nothing of concrete value.

***

From those private few we may hope for public spirit, amenities once of our own making now offered up as "charity."

A while ago, returning a book borrowed for me from the Robarts Library, I got to see the place for the first time in ages. I found not the black and mahogany world I'd known, but buffed beige, green glass, and row upon row of computers. The whole ground floor is now the Scotiabank Information Commons.

It's marvellous, a wonderful resource -- apparently too wondrous for a public university to afford. Hence the Bank of Nova Scotia, its admirable largesse -- and its promo on every screen, in the margins even when screens are in use.

The bank can afford things like that, the university cannot: as a society, we have decided public institutions should not. Schools, hospitals, environmental protection, public transit -- all their budgets slashed. As an act of God. What can I tell you? There's simply no money. That's just the way it is.

But there's plenty of money. We've simply decided to put it in private hands and then be happy for a few handouts. And hey: it seems to work just fine. It's efficient after all -- even given what bank presidents earned compared to bank tellers. (Wait: there are no more tellers, or soon won't be.)

But what goes, in the name of efficiency, is accountability. We have no collective control over what we get -- but for our much touted "influence" as "consumers," who make "choices" from among the few options offered by the corporate world. (Will that be Coke or Pepsi?)

We -- as a society, governments our agents -- once decided what was worth having. Now we get (or not) only what global capital decides we're worth.

In the fall of 1995, after the tax and service slashing Harris Tories won the government of Ontario, people took to the streets by the thousands in huge "Days of Action." Confronted by the usual "fringe elements" the Tories unsurprisingly stuck to their agenda.

One wag noted an irony in those protests: the very people once in the streets screaming "Smash the State" were now out there trying to save it. Even from itself.

***

|

Public amenity too grand

|

Public amenity is meant to be mean. That's so you'll know "public" means not that it's yours, but that you have it on sufferance, the minimum on offer to those who can't afford any better.

In rare instances, it's all you can get. Since prohibition ended in Ontario in 1927, the province (like most provinces) has had a near monopoly on alcohol. Canadian vintners and brewers can sell through their own stores (but not to other stores); for spirits and most imports you have to go to the LCBO.

For more than 40 years the Liquor Control Board of Ontario put the emphasis on control. Their outlets displayed not bottles but rows of charts. One made a selection, passed a slip to a clerk behind a counter, and waited for the hooch to be handed over.

The first self service stores opened in 1969, and soon learned marketing. Twenty years later some were positively elegant. The one at Toronto's Manulife Centre came to include a kitchen for wine and food instruction, its windows showing even greater style, on them a parody of high end retail: "LCBO: Toronto - London - Paris - Pickle Lake" -- all of course in Ontario.

In 1996 the new Tory minister in charge called this appalling extravagance. How dare the managers of a public booze outlet make the place appealing (and have a little fun). His true target was not "waste" or "inefficiency," the usual right wing bugbears. It was pleasure, even wit, linked to public enterprise.

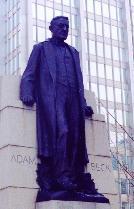

The Tories wanted to privatize every Crown corportation in their grasp. The biggest was Ontario Hydro, born of a Conservative government in 1906, by 1917 buying out private companies and their turbines at Niagara to create one of the world's biggest utilities -- publicly own.

And honoured: its founder Adam Beck, knighted for his efforts to bring public power to the people, stands on University Avenue, in bronze atop a concrete waterfall.

Sixty years after its birth, other Conservatives broke up Hydro -- into morsels tempting for takeover. TVO, the public education network, was put on the block too (no takers; they'll try again).

The LCBO would have been -- but was making too much money to let it go quite yet. Maybe they'll try the usual privatizer's trick: make it grim and mean again, letting big corporations vend spirits with more flair.

Then maybe they'll try it with health care.

***

Irony? Hardly: National Post, pg 1, Nov 19, '99. A good news story for Conrad Black's right wing sheet. The subhed: "Analysts applaud." |

The public good is meant, more and more, to depend upon private charity. What we once provided together, with and for each other, we now have to beg from our "betters."

Have no doubt: they will be our betters, even trying, when they bother, to be very good. Charity can feel very good indeed: it is better to give than receive (just ask anyone on the receiving end).

Giving makes you feel so noble -- noblesse oblige and all that, if in truth they're hardly obliged these days. But it does look good, feel good -- and for many that's the only good reason to do it. Paulo Freire called this "false generosity."

-

Any attempt to "soften" the power of the oppressor in deference to the weakness of the oppressed almost always manifests itself in the form of false generosity; indeed; the attempt never goes beyond this.

In order to have the continued opportunity to express their "generosity," the oppressors must perpetuate injustice as well. An unjust social order is the permanent fount of this "generosity," which is nourished by death, despair and poverty. That is why the dispensers of false generosity become desperate at the slightest threat to its source.

True generosity consists precisely in fighting to destroy the causes which nourish false charity. False charity constrains the fearful and subdued, the "rejects of life," to extend their trembling hands.

True generosity lies in striving so that these hands -- whether of individuals or entire peoples -- need be extended less and less in supplication, so that more and more they become human hands which work and, working, transform the world.

In Ontario, among other places, the "rejects of life" must now extend a supplicant hand with some caution. In a province (and country) long proud of its sense of social conscience, people have been given permission by their own government to suppress it, even to resent any presumption of it.

Long upset by people homeless on the street (put there by the meanest housing policies we've seen in years), panhanding, begging -- worst of all taking innocent motorists by surprise with a quick squeegee across the windshield -- Ontario's Tories decided to do something about it.

Affordable housing? Decent jobs? Those cost money -- and of course there is no money. Symbolism comes free (to all but those turned mere symbols): in November 1999 they passed a new "Safe Streets Act" -- safe for whom I hardly need tell you.

The real crime of street people is their mere visibilty, getting in the face of nice middle class folk who'd rather not see such blatant poverty, thank you very much -- even as their cherished tax cuts help create it.

So the rejects will be pushed out of view: to underfunded social services; to prostitution, petty crime, or to prison, where they'll be schooled in crimes not so petty.

Many called the move mere grandstanding. Even a Tory flack said (on TVO): "A bad policy -- but great politics." Politics of a sort we've seen before: authoritarian; reactionary. Scare "respectable" people of some riff raff or other, then promise a solution to sweep them away.

Out of sight, at least.

***

I've been kept honest by knowing so many waiters, bartenders, table dancers & street hustlers -- & so few of the people who see them as no more than servants.

Well, the usual bleating of a liberal heart bleeding at the demise of social conscience. But I am no liberal, no kind hearted soul happy to decry injustice from a safe distance. I've seen it up close, if less in my own life than in lives around me.

I have been kept honest by indigent kids.

I once watched trucker / busboy Martin try to fill out a deposit slip. It was a struggle; I wondered how he faced an income tax return (but then maybe he didn't).

As a Newf kid in the big city, Shel's native intelligence translated easily to street savvy. But off the streets it could work less well. Charm thwarted could turn to bravado, behind it just a hint (if only a hint) of force.

But it made no dent on cops, social workers, hard nosed bosses. They'd seen it all before; they knew who was in charge and it wasn't some mouthy working class kid.

The world does not belong to people like Martin or Shel. They don't know its deepest rules: subtle, covert, middle class. A mere glance from their "betters" is enough to call up a profound and resentful awareness: I am incompetent; I have no power short of my fists. And I know where my fists might get me.

They both retained another working class birthright: a deep sense of fatalism. No matter how hard they tried they were unlikely to escape a hard, frustrating life.

Yet through it all I could see Shel retain too a proud sense of honour. One night at George's Townhouse early on, Shel still sussing me out, he said, "I think you're a decent guy." I told him Rick behind the bar had said the same of him: "Shel's a good kid. He's decent."

Given the life Shel had seen, able to presume nothing, he might have been no more than a charming con artist. He had the skills, heaven knows the charm. But he wasn't: he was decent.

Shel taught me that simple decency ranks high on the scale of human values. Much higher than what may pass for values among those free to count as their due the presumptions of higher class.

***

Feminism said that the distinction between men and women was history's most fundamental divide. Marxists, of course, said it was class. I had found feminist analysis useful but in time, all around me, differences of class grew much more apparent.

Tory consultant Jan Diamond batted not an eyelash in accepting $100,000 from Ontario's fervent fiscal conservatives for advising them on how to slash payments to people on welfare.

A Tory minister earning as much (on top of considerable private wealth) was happy to give indigent single mothers helpful advice: Show some initiative! Go bargain for tuna in cheap dented cans.

By the standards of those whom (no, on whom) they advised, these people lived in luxury. But not in their own minds: My perquisites are nothing unusual; my advice is worth $200 an hour, maybe more -- because the market says so. Just as it says one basketball player is worth 400 nurses. Or 600 daycare workers.

I have seen people claim their "full market value" out of no more than posturing charlatanism (no names need be mentioned, having been already). I have seen them get by on sheer style -- and well, those sharing their place in the world easily conned by style. I have seen among some of them not an ounce of true decency.

But people like that run the world. Men and women both.

These excesses have nothing on, say, courtiers at the Versailles of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette (before they literally lost their heads). But they are rooted in exactly the same blasé presumption: this is simply how the world is.

***

I have known too many gay people happy to share that presumption. Well, not many; none I've paid much attention here. But more than a few; more than I'd ever hoped to find.

I once had a set to with a gay couple, friends of friends, appalled at "explicit" ads on the back of Xtra -- that back sometimes flipped front, even in their own suburban public library. One of them, once married, still believed most people didn't know he was gay -- the usual story, the one in the closet so often the last to know.

I wrote to Jane about them (in rather a snit):

-

They are trying to be "respectable" homosexuals: coupled, domestic, living as well as they can (which, for some, can be quite well); maybe finding some politics in classic minority- based gay rights -- but not fundamentally questioning the way the world works beyond that one, inconvenient bit of discrimination. And my dear, if we go about flaunting it, what else can we expect?

They are smart, privileged; their willful ignorance and fear seem craven to me. I've seen people who have worked past it. More to the point lately, I've seen people who could never afford it: visibly poor or queer or both -- and they just have to cope.

And do, not always well, but with more honesty and courage -- and, some of them, generosity -- than I expect from well heeled cowards with a house in the burbs and the occasional tourist trip to naughty downtown.

I said at the end of that rant: "I'm so glad to have known so many waiters, bartenders, table dancers and street hustlers -- and so few of the people who see them simply as servants."

***

Most of us, most of the time, are servants. We spend much of our lives subject to the whim of our "betters" -- at work.

It was Paulo Freire, as we've seen, who said preventing others "from engaging in the process of inquiry" is a form of violence. No matter the means, he said, "to alienate men from their own decision- making is to turn them into objects."

For the vast majority of us, nowhere in our lives are we most "objects" -- most subject to the most normal, ordinary, even casual sorts of such violence -- than on the job.

At the beginning of this website I said "I believe that work is central to life, the very thing we are here to do; one might say we are what we do." But only if we're very lucky. For most people a job is necessary to make a living, but it's rarely the life they want, not what they might hope to be -- "a living" not living itself.

This would be criminal (and in truth is) were it not deemed essential, expected, merely normal. Most of us work for someone else's gain. We must be "cost effective." We must be "efficient" -- though to what effect but money no one seems to care.

I have been very lucky indeed, lucking into work where I could be what I did, and want to be. It never made me much money. But it gave me work I wanted to do, work -- and life -- I could value. It's a luxury most people never get a chance to find.

It shouldn't be a luxury. It should be the way we are all free to work. Not just to be nice -- but because we work better that way.

***

|

Beyond biz guru gimmicks

|

The older & bigger an operation gets, the worse it is: founding purposes lost; goals put off to some vague future; the present all about means, not ends.

Organizations come to have only one true goal -- their own survival.

It is a truism of modern management studies that people work most effectively when they care about what they do and have some say in how they do it. People want to grow and learn -- not just earn -- on the job.

I got to read a lot of business books in my policy wonk days, at the Press, at ACT, even back at the library in 1974, doing that big management study. In the biz guru boom of the '80s and beyond, most were crap.

Many were gimmicks: The Five this; The Seven that; even The One thing you need to make your business take off like a shot -- with not a thought: Just take my pill and get over it. Fad diet books boomed at the same time.

But I learned to read through the Magic Bullet stuff to perceptions often familiar. People work for more than money -- when they're allowed to. People get committed to what they value, what they share; they'll work hard to reach goals they themselves help set.

Even what seemed gimmicks could have substance. Stephen Covey's The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People peddled (at great profit) truisms as old as time: Put first things first; Listen before you speak; Use the right tool for the job.

But I could hardly object, truisms often true. His Habit Number 2 seemed quite familiar: "Begin with the End in Mind." (Do I hear there: "What's it for?") And when the dedication reads: "To my colleagues, empowered and empowering" -- well, I'm inclined to read on just to see if he means it.

Covey did, in principle (calling a later work Principle- Centered Leadership). So did Peter Senge, in The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization.

His "disciplines" again reiterated simple sense: Know thyself; Question preconceptions, especially your own; Share your vision; Learn to learn with others in true dialogue, not lectures; See the whole, not just the parts.

If you and your organization failed to learn, change, become all the time -- you were sunk. Adapt or die.

***

That such simple advice seemed the voice of oracles, gurus, prophets, showed only how dishonoured prophets can be in their own land.

Edward Lawler in High-Involvement Management knew well that trendy CEOs could love a fad but hate real change.

- No more fundamental change could occur than that involved in moving power, knowledge, information and rewards to lower levels. It changes the very nature of what work is and means to everyone.

And that is truly scary. Peter Block, in The Empowered Manager: Positive Political Skills at Work, made it clear: people all across an organization can be stuck in a "bureaucratic cycle" of dependency, patriarchal assumptions, myopic self interest, manipulative tactics.

Heaven knows. And the older, bigger, and more structured an organization gets, the worse it is: founding purposes forgotten; goals put off to some nebulous future; the present all about means, not ends. Organizations come to have only one true goal -- to perpetuate themselves, their only engine that "bureaucratic cycle."

I saw this at the AIDS Committee of Toronto: born of community; knowing how to work cooperatively, even collectively -- coming to run on bureaucratic fear. Activists became "employees," their voices irritating, their visions disruptive of rational, "business like" order.

I left ACT because I was sick, and getting sicker. An odd irony that: as a person with AIDS, I had to leave an AIDS organization to keep it from killing me.

Only later did I learn exactly how the things I'd seen at ACT -- common to most workplaces: initiative suppressed; ideas ignored; committment squashed flat -- actually can kill people.

***

Radical science: Masses of data pointing to massive need for the "reconstruction of working life." |

The authors, good social scientists, may not have set out to write a manifesto. But Healthy Work, if put to work, could be truly revolutionary.

Stress is bad for us, right? Well, maybe not: it depends on where that stress comes from and what we can do about it.

After leaving ACT I found a book that showed just how unhealthy that "health organization" had been. It was Robert Karasek and Töres Theorell's Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life.

Looking at scads of studies they showed that stress was not the villain. It was lack of control over how one might meet that stress.

They ranked jobs on a grid: one axis the demands of a job; the other "decision latitude" -- the level of control -- one might have in that job. High demand work was actually invigorating -- if one's level of freedom to decide how to do it was also high. Low demand and low latitude made people passive, even off the job.

Low demand / high control was of course a piece of cake, if maybe a bit boring. High demand / low control was a recipe for illness, directly related to levels of exhaustion, depression, pill popping, and heart disease.

Top architects had it easy; watchmen and janitors could be slugs. Doctors, teachers, even farmers faced more stress but had more leeway in how they faced it. Waitresses, nursing aides, phone operators, gas jockeys -- well, need I tell you?

High demand and low control practically define low status jobs (remember how I went on about "receptionists"?) -- such jobs most often "women's work."

It also defines jobs that make people sick. Karasek and Theorell, as the book's blurb said, "identify a clear connection between work- related illnesses and workers' lack of participation in the design and outcome of their labors."

They went even further, as I told Jane:

-

This isn't about workplace health promotion as occupational safety drives or anti smoking campaigns. It isn't even about simple stress, sometimes unavoidable. It is the writers say (in a beautifully direct line in an otherwise complex book) about "the work environment where stressors are routinely planned, years in advance, for some people by others."

It is about how work is structured, where power rests, about the fundamental politics of how people work together, their need for engagement, meaning, growth, esteem -- and what happens to them when they don't get it.

It's a well founded, calmly scathing critique of "normal," "rational" work practices that make people anxious, unproductive, finally passive and sick. (And then the people with the power to determine these practices complain about the cost of health care!)

I can't quite imagine that Karasek and Theorell, good social scientists, set out to write a radical manifesto. But Healthy Work, if put to work, could be truly revolutionary.

***

I thought I'd have a chance to put it to work -- at Pink Triangle Press. I'd known it as a workplace built on engagement, on the involvement of everyone we could get our hands on. But for commitment freely given, it would have died at birth.

But by the mid '90s the Press was nothing like what had birthed it. The Body Politic was dead, and so was the culture that had kept it alive. That culture had been gift culture, based on what people could give away -- to each other; to themselves together.

Dependence on free labour was sometimes messy, certainly not "efficient." It was simply essential. It was also something more: creative; dynamic; a way to go on becoming, new people helping shape the place anew all the time. As Sue Golding said: "The interesting problem was to decide who this we thing was."

"We" were ever changing, if around a relatively stable core of people and values. The place was porous: anyone could walk in, or send in a piece or two. Some, as anywhere, didn't make the cut. But many, from tentative beginnings -- all those toes in the water -- became central to the life of the paper.

They were free to because they did it for free. The Body Politic never had to worry whether it could afford new blood. It arrived at no cost but the time and energy spent to keep new people involved, committed. They were worth that: we needed them.

The Press, I found, got only what it could afford in cold cash. It was no longer a gift culture but a commercial one: everyone was paid, for everything. That didn't mean everyone worked just for the money: there was still commitment to purpose (if purpose too often unclear). But the basis of exchange -- setting expectations; setting the culture -- was cash, not commitment.

There was, by my mid '90s stint there, not even the memory of gift culture long vital to the enterprise. Philip Fotheringham once gave the ad staff a free sail on the harbour, I with them. Someone asked how I knew Philip. I said he'd been a volunteer at TBP. "You mean," he said, "there were volunteers?"

By then there were none, the last ones (in Toronto at least) made employees a few years before. None was recruited after that; none needed -- none wanted. With that the once porous boundaries solidified, froze shut -- freezing out anyone not willing to apply for a "job."

It was, I see in retrospect, the most significant sea change in the entire history of the Press.

***

For people at the Press now, it was a job. Maybe not just a job, but a job nonetheless: normal, real.

With that came all the normal "realities" of the workplace. Ken Popert was right to worry that there were no personnel policies, hiring me to create some. They needed some rules, no longer having in common a coherent set of values.

So I brought my own workplace values, learned in no small part years before in that very workplace. I hoped others might share them -- or at least find them worth learning. Some did. But if they were to become widely shared they had to be shared most strongly by Ken: his style, his beliefs made known, could shaped the place to his will -- or what are "guiding lights" for?

Ken was wary of guiding, and for good reason. In a 1998 Fab National piece on the history of the Press, Michael Riordon asked Ken if there was anything he missed from TBP's collective days.

-

Yes. I miss the vitality of strong and competing opinions that used to produce the final synthesis that appeared in the pages of The Body Politic. Mine was only one of them. But now I have to be more careful, with my voice carrying proportionately so much weight.

[Michael asks: As the boss?]

Well, I was looking for a more graceful way of saying it -- but yes.

Ken feared dominating, knowing his gut impulse was precisely to dominate. So he delegated substantial authority to local publishers in Toronto, Ottawa, and Vancouver, and to directors of other Press projects. As president and executive director of the whole thing he stood back, hands off.

A noble stand, in principle. But too often it came to mean: I'm just the president; I can't determine what the Press is and does from day to day. He could have influenced it, guided it, called it to principles often he alone might recall. At times he tried, if rarely to much effect. As ever, Ken couldn't find a middle ground.

I once said to him: "You can't see any role for yourself between keeping your hands off -- or having them around someone's throat." He agreed, if a bit chagrined, fearing his guidance would likely mean not just a hand but a boot to others' throats.

In the end no one guided the Press -- but for its commerce (that not just guided, but guiding). As a project once caught up in the politics of both the workplace and the wider world, it was adrift.

In that tempting comfort hierarchy can offer, everyone got to say: I'm just... whatever. It's not up to me. I'm just doing my job.

***

Not in Canada

Section 15, the equality provisions of the Charter of Rights & Freedoms, has two parts: one setting grounds on which bias is not allowed (the list deemed not exclusive); & one saying when discrimination is allowed. It reads:

"Subsection (1) does not preclude any law, program or activity that has as its object the amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged individuals or groups, including those that are disadvantaged because of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability" (that list not exclusive either).

In a 1994 essay, Why treating people the same doesn't make them equal, David Vickers, now a justice of the BC Supreme Court, noted that "Our country developed differently than the country below the border," yet many Canadians "still believe that 'sameness of treatment' means 'equality.' Similar treatment often generates very, very different results," he wrote. "The impact of some laws will vary depending upon a person's economic or social or cultural reality. ... The first lesson of equality is to understand that equality means accommodating differences."

In Canadian jurisprudence this is "substantive equality" -- not the "formal equality" of treatment or opportunity that can lead to unequal effects. "The fundamental notion of equality in this country," Vickers said, "is to address differences."

Sadly, it's a piece of our heritage often ignored -- especially by gay people seeking "equality" by pretending they're the same as everyone else.

* "The law in its majestic equality forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread."

-- Anatole France,

Le Lys Rouge, 1894 (with thanks to Craig Patterson for the reference)

Speaking of conflict...

The year 2000 saw Pink Triangle Press back in court, as reported (in fab, of course), "fighting lawsuits seeking nearly $4 million in all. PTP is also seeking justice on its own, suing a local businessman for $1.5 million."

That businessman's case began with a 1996 Xtra story that he says defamed him, writing a letter about it to fab -- in which, the Press claimed, he defamed Xtra: time for some litigious tit for tat. In 2001 the Press backed off, with an apology & a six figure payout.

Another defamation suit comes from a former employee, accused by the Press of racial slurs, & fired. Details, of course, remain contested. Clearer (& quite interesting) is a line in her letter of dismissal, accusing her of "insubordination through openly criticizing senior managers of Xtra in front of staff."

Sounds like someone there studied at the Carol Yaworski school of management.

Ken let me toss my values around, testing them, seeing how far I might take them. He rarely let on what he thought of them -- until he'd had enough.

We came to a fight (if as ever a restrained one) over leave policy. To me it's the classic case of employers trying to run employees' lives -- because they've failed to run their own businesses well.

Sick leave, bereavement leave, pregnancy and parental leave (those last the only ones dictated in law) -- what difference did the reason make? What business is it of one's boss? The point was: someone would be away for a while -- and the boss hadn't planned how to cope. So you, not he or she, will have your life restricted by lots of stupid rules.

And the same rules for everyone -- as if distinct people don't have distinct needs. The notion that equality means sameness, scorning "special treatment," is a nice liberal idea utterly ignoring where the definition of "same" is likely to come from.

Leave provisions are not an entitlement, but a reasonable and humane accommodation of needs -- a concept enshrined in Canadian (if not US) constitutional law. Needs differ, a point wonderfully put in an old phrase, it origin unknown to me: "The law prohibits rich and poor alike from sleeping under bridges." *

I began by challenging "equality equals sameness." In a set of principles to guide all employment policy, proposed by me and adopted by the board, was this:

- Creating healthy, productive working relations, through openness of information & ideas, cooperation toward shared goals, & recognition of diversity in treatment meant to achieve fairness of effect [emphasis here mine].

Then I tackled the real issue behind intrusive limits on leave, in a policy on "operational continuity." Through cross training, shared knowledge, continency plans and the like, the employer became responsible for seeing work got done even when some workers were away -- the key point being how long they'd be away, not why. That flew well enough.

That done, I said reasons for leave were no longer the boss's business. Any reason "given in good faith" was good enough. If you don't trust the people you work with, I said, you've got a problem no leave policy can fix.

***

That sounded pretty good too -- until Ken had second thoughts. They were of the classic "what if" variety, in a memo to me.

- To pick a hypothetical (but not out of the question) situation, under the policy as written, an employee who believes in astrology would be entitled to seek occasional leave on the grounds that the stars indicate that today is an unlucky day for work and that they would therefore be unable to work today because of stress and worry. Such leave could fairly and honestly be sought frequently and, under this policy, would be allowed. ... By the way, this document states that leave is not an entitlement, but if the removal of supervisory discretion does not constitute an entitlement, what does?

As I said to Paul Pearce: so, Pink Triangle Press ends up before the human rights commission trying to prove that astrology -- no more absurd than belief in an Old Testament God -- is not a religion protected from discrimination.

I gave up on that policy. Ken said I was "pandering" to staff, so I left him to decide how to handle that (and them). I left his employ just after that, though did offer to continue, as a volunteer, some work I'd already started.

***

That work was on conflict resolution, training others to be Counsellor Troi, dealing with a place where, as one put it, "being nasty gets you ahead."

A session on March 20, 1996 was held in an office next to Ken's, so he got to hear it all -- endless crabbing. I knew they could get past it, on to things more productive. Maybe they did. But I wouldn't be there to find out.

On March 27 Ken sent me a memo, by fax at home, saying what he'd heard was "an uncontrolled bitch session behind closed doors," inducing "a state of anxiety and suspicion among our supervisors." In an attached memo to those in training, he said:

- Rick says the Press will have to remove a host of obstacles, including "an enviroment that creates conflict." (I don't really understand that, since he seems to be saying that the only environment in which trained conflict resolution facilitators can properly function is one where there are no conflicts.)

Ken planned "to purchase appropriate professional management training" to complete the process. I was fired. I called him and said: Fine. Good luck.

I took some satisfaction in being, best I know, the very last person ever to work for free at what was once The Body Politic.

Ah, Ken, ever the Cartesian, long a quandary for me. I've quoted him here often, his words incisive, illuminating, his logic crystal clear -- sometimes even to the point of absurdity. His is the most blinkered brilliant mind I have ever known.

***

I used to fret that. I don't anymore. Ken runs a business, in financial terms a huge success. In that interview with Michael Riordon he said:

- Now our papers are in a much better position to take risks than The Body Politic ever was, precisely because they have an organization with substantial resources to stand behind them.

Yet the Press has never taken risks the way The Body Politic did. It had no cash to cushion likely blows; the only "substantial resources" it could count on were human ones.

It was our very marginality that made us not simply willing but able to take those risks. Security does not foster radical vision; property -- and fear of its loss -- can make conservatives of us all.

I no longer fret the role or fate of the Press -- because I have none but the faintest hope for it. Change will come only as it did in 1971, when new people with new ideas decide to make something fresh and exciting and new. And their own.

To me, Pink Triangle Press is now just one more business on Church Street, like most doing some good things, some not so good, guided no more than most by any sense of social vision.

Beyond, of course, being "gay."

Go on to Citizenship: In the city & on the street

Go back to Contents

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/citizen1.htm

January 2000 / Last revised: October 8, 2001

Rick Bébout © 2001 / rick@rbebout.com

Visionary; his vision lost:

Visionary; his vision lost: