QUEEN STREET

Downtown

Glory of Empire

The South African War Memorial,

& other monuments

to lost boys

|

"To Our Glorious Dead"

The Cenotaph at Old City Hall: Canada's wars, 1914-1918, 1939-1945, & 1950-1953, remembered here every November 11th, some living to remember. Remembered only by the dead: 1759, 1812-14, 1837-38, 1866, 1885. |

Anyone forgetful, as Canadians can be, that our country has a distinct history -- its tales quite unlike those told by our American cousins -- need only go stand, as I often have along Queen and beyond, before a war memorial.

Among dates there one will not find 1776, except perhaps marking the final rout of Americans invading Quebec under (among others) Benedict Arnold. More likely 1837: a Rebellion, not a Revolution, and a lost one. Not 1865 but 1866: volunteers fending off the Fenians, Irish Americans attacking their British oppressors by the shortest possible route. Confederation's 1867 is rarely seen on war monuments, the Canadian state born not in blood but at conference tables, in compromise.

One can find 1812-1814, on American plinths too; but in that war Canadians and Americans were enemies. Also on both sides of the border: 1950-1953; but Korea was a United Nations "police action." We don't see here, etched in stone, names of Canadians lost in Vietnam -- though some were, serving in the US, not their own, armed forces.

We can of course find the two World Wars: 1914-1918; 1939-1945. But note those opening dates: each time, Canada was at war for more than two years before the US intervened, in 1917 and 1941. In its neutral years isolationist America could fret a combattant on its northern border. One nervous 1940 tome was called Canada: America's Problem -- "Rival? menace to peace? or partner?"

In the Great War (as it was called until the next one) Canada's role was assumed: Britain's August 4, 1914 declaration against Germany had been made for "all the King's Dominions." There were then eight million Canadians; more than 61,000 would be killed in that war, some 173,000 wounded -- a greater share of its people than any other nation save Australia, also fighting to make the world safe for the British Empire.

By 1939 Canada was formally independent, if still senior dominion of the British Commonwealth. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King pushed the point -- a bit: he didn't ask Parliament to commit to war on September 3, when Britain did; he held off by four days, not putting the question until September 7.

Three days later (with five members dissenting) King could assure the King that his North American subjects were on side. Convoys of Canadian sailors and merchant seamen (Newfoundlanders too, if not Canadian until 1949) were fighting the Battle of the Atlantic well before anyone had reason to remember Pearl Harbor.

|

Rule Britannia!

"To the memory and in honour of the Canadians who died defending the Empire in the South African War 1899-1902." |

Towering over Queen Street at University Avenue, we get dates that few Americans are likely to recall: 1899-1902. Nor, in fact, many Canadians: the Boer War gets glossed over even in our own history books.

Boers were mostly farmers, often itinerant, descendants of Dutch settlers planted at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652. Wandering north this "white tribe of Africa" had run into a much bigger and more settled one, the Xhosa -- skirmishing with them for nearly a century, taking their land for cattle and some Xhosa as slaves.

The British struck the Cape in 1795, securing it as a colony by 1806. Many Boers set off on the Great Trek beyond the Orange and Vaal rivers, founding the Orange Free State and, in Transvaal, the South African Republic. By the 1850s, both were independent of Britain.

They might have remained so but for the discovery of diamonds and gold -- by the white tribe: black ones had long mined gold, building an active East African trade. By the 1890s Transvaal had the richest mines in the world -- beyond the control of Britain, its economy on the gold standard, its empire under threat by Germans on the high seas and in South West Africa.

On October 11, 1899 British troops moved in to take the Boer states; by 1902 they had. In 1910, with the Cape Colony and Natal, they were made the Union of South Africa. In time the Boers would be back in charge: their National Party took power in 1948, elected solely by the white minority; the Age of Apartheid was born. It would last more than 40 years, Africa's white tribe vilified as the world's most unrelenting racists.

But in the Boer War, and long before, everyone had been racist -- "race" meaning more than we take it to now. If still absurdly: fixed race has no natural reality; it's a category of social power long backed by spurious science. The Nazi's "master race" eugenics was not an aberration, but a brutally logical application of ideas widely held at the time.

To the British, touting "the genius of our island race," defiant bush farmers speaking bastard Dutch Afrikaans were no more part of "our race" than were, say, Italians. And to Boers, the British were Uitlander, unworthy of the white tribe: denial of English miners' rights had been Britain's pretext for launching the war. Long before, they had been as brutal as Boers in clearing Bantu tribes from "British" land.

Despite having sent half a million troops against the Boer's 80,000, the war began badly for the Empire. Lord Kitchener turned to scorched earth, barbed wire and blockhouses. The South African War likely saw the first detention centres ever to be called concentration camps, Boers the first "race" ever herded into them. More than 20,000 women and children died there.

Canadian history textbooks rarely offer such details. The Boer War often appears as just one more episode in the endless contention of our own "founding races" -- English Canadians, still hot from Victoria's 1897 Diamond Jubilee, fired with pride in Empire; French wary of imperial adventures, having been on the receiving end in 1759, ever remembering The Conquest.

Or, it's seen as a milestone on this country's long road to "nationhood." Canadian troops had never before fought overseas. In South Africa, George Stanley wrote, they "bore themselves with distinction ... in the grim fighting at Paardeberg in 1900," later "marching triumphantly through the capitals of the Orange Free State and the Transvaal."

They had been sent off in a rain of flowers, crowds roaring out Rule Britannia!. "Never before," the Globe glowed then, "has Toronto been more enthusiastic in honouring her valiant sons." Bold young Johnny Canuck, a big boy at last -- off to bash the Boers.

|

Sculptural shifts

Walter Allward's early heroic works noted on University Avenue. Below, his greatest work, in France: "mourners, torchbearers, figures of peace and justice"; the Canadian Memorial at Vimy. |

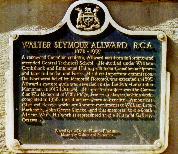

A historical plaque near the South African War Memorial tells us not of that war, nor even of this monument, erected in 1910. It recounts instead the career of its sculptor, Walter Seymour Allward. His earlier works had hailed Canadian troops who'd fended off the Americans in 1813, and crushed the Métis in the Northwest Rebellion of 1885.

But Allward's greatest work came in 1936, rising from a battle of the Great War: the Canadian Memorial at Vimy Ridge, in France, if on 100 hectares made by the French forever a part of Canada. In tales of this country's "coming of age," no word echoes with more resonance than Vimy. There, on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1917, Canadian troops attacked the ridge; in a week they had taken it from the Germans -- as the French and British had repeatedly tried, and failed, to do.

The empires of Europe has launched the Great War in fits of Honour and Glory, each expecting "a lovely war" and a swift knockout blow, their brave boys home by Christmas. They got more than four years of the first "total war": 65 million troops mobilized, many conscripted, for modern mechanized mass slaughter.

By November 11, 1918 casualties would number some 38 million (not counting civilians); of them, nearly nine million -- and most of those empires -- lay dead, the "flower of their generation" rotting beneath ravaged fields. In The Stone Carvers, her novel of the men whose hands shaped the memorial at Vimy, Jane Urquhart writes of Walter Allward seeking models for:

- "the figures of defenders, mourners, torchbearers, for the figures of peace and justice, truth and knowledge.... In the end it was the imposing front wall of the memorial that obsessed him, the wall that would carry on its surface the names of the 11,000 no one ever saw again."

Or not there: of the 11,000 Canadian casualties at Vimy, some 3,000 were killed.

The memorial's two pylons, tall enough to be seen from 60 kilometres away, stand not in bombastic glory, but in towering, monumental grief. To mythologists of triumphal "nation building," the word Vimy may stand for Heroes; to many more Canadians, still, it stands for The Dead.

-

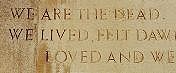

"We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields."

I came upon that stanza at another monument, near the tower of Hart House at the University of Toronto. The Soldiers' Memorial Tower, it's formally called, rising in 1924. Names of the dead from the Second World War have since been carved on walls inside its portal; those of the First, there first, line a sheltered alcove just beside.

Along with that poem, all three stanzas. The first lines every Canadian schoolkid learns by heart: "In Flanders fields the poppies blow / Beneath the crosses, row on row, ...." The first stanza is on our new $10 bill, in tiny script, with poppies and vigilant peacekeepers.

I'm not sure how many know the second, above. On the south wall flanking those names of the dead at Hart House, where I took that picture, it seems the last: the third stands alone, on the north wall. It reads:

-

"Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders field."

Not educated Canadian, I didn't know that part. Standing there, I found myself hoping the poet -- John McCrae, a doctor born in Guelph, Ontario; among the dead by 1918 if of pneumonia in hospital at Boulogne -- had not really meant it. Not after that direct, first person address: "We are the Dead."

I've since learned that war poems in which the dead speak are not all that rare: even Kipling did it. But, after the power of that second stanza, its simple appeal to life ("We lived... Loved and were loved"), I'd like to think McCrae's closing lines were, in a way, obligatory: formal, imperial, even Kiplingesque; truly breaking faith with the Dead. And the living. But I don't know.

Growing up American, a war having made me Canadian, I'm not fond of bronze and stone raised to glorify arrogant folly, blind obedience, and senseless slaughter. But now, here, standing before war memorials, even as I see all that still, I see something else: the faces of boys. Kids really, many not yet out of their teens. And dead.

I don't know who they were; whom they may have killed, women and children likely among them. Nor do I know what drove them: patriotic fervour? imperialist jingoism? cruelty? Perhaps fear -- of getting killed themselves, or of failing to fit in as "one of the boys." Maybe it was just the promise of grub and gear and a job, not always easy to come by, freely on offer -- along with honour and glory -- to boys willing, if likely not eager, to die for King and Empire.

I don't know what their choices may have been; what power they had even to make choices. All I know is that they did it, in their thousands: living boys, each life unique, now lost among "Our Glorious Dead."

In The Stone Carvers, Urquhart pondered boys lost "in a messy burial without a funeral, without even a pause in the frantic slaughter":

- "Who were these boys with their clear eyes and their long bones, their unscarred skin and their educated muscle? How was it possible that they were destined to be soldiers? In what rooms had they stood? In what shafts of sunlight? Prairie grasses quivering beyond the old watery glass of farm windows. Snow falling softly on small uncertain cities, or into the dark lakes of the north. And all the footsteps they left in the white winter of 1914 would be gone by spring."

Faces of boys: some in bronze; a few in old newsreels. And many more in my mind: they can't have been entirely unlike living boys I've known, many of them, too, now dead. And remembered -- if rarely as "glorious dead."

But many, I know, were glorious in life. And I can't but imagine that many of the lost boys I find dead in bronze and stone were also, truly, glorious. Alive.

See more on:

The Vimy Memorial, in Losers -- Who sometimes win, an addendum to Promiscuous Affections.

The War of 1812, & the 1813 Battle of York, in York's fort; Toronto's reserve.

Sources for this page: John MacCormac: Canada: America's Problem, Viking Press, 1940. George F G Stanley: "The Fighting Forces," in The Canadians: 1867 - 1967 (J M S Careless & R Craig Brown, eds), Macmillan of Canada, 1967. We Stand on Guard: Poems and Songs of Canadians in Battle, compiled by John Robert Colombo & Michael Richardson, 1985. Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1998. Jane Urquhart: The Stone Carvers. McClelland & Stewart, 2001. Linda Logie (correspondence, on war poetry, July 2002).

Go on to: SPACES

Blight & the Brave New World

Rural estates to urban rewewal: Moss Park, Trefann Court, & Corktown

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/downtown/2pboer.htm

June 2001 / Last revised: November 13, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com