QUEEN STREET

The life of a city stream

Of time & the river

The Don:

salmon to sludge to concrete;

in time, to life revived

|

Reckoning time

Sir Sanford Fleming, 1879: time by the trains. Below, Eldon Garnet, 1990: time by the river.

|

|

The river above

View south off the Queen St bridge (at the top of this page, a view north); another from farther south: The Don hemmed & ramped by its namesake, the Don Valley Parkway.

|

Back along Queen just west of Church, there's a very short street called Berti. It runs just a block, south to Richmond; it houses nothing of note but a low brick block long announcing itself to Queen with a sign hanging over the door. It's a place you likely won't know unless you've done (or nearly done) time: the sign said "Bail and Parole." Last I went by, it was gone.

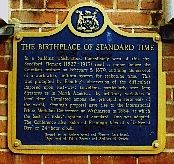

But if you have (free) time, do wander down. Still there on a wall beside that now unsigned door is a plaque, also doing time. Or its history.

- "The Birthplace of Standard Time: In a building which stood west of this site, Sanford Fleming (1827 - 1915) read a paper before the Canadian Institute on February 8, 1879, outlining his concept of a worldwide, uniform system for reckoning time. ... Fleming's proposal gave rise to the International Prime Meridian Conference at Washington in 1884, at which the basis of today's system of Standard Time was adopted."

(The plaque has lately got graffiti: "Ghost was here.") Fleming, later Sir Sanford, was an engineer, his business railways: he wanted trains to run on time. Or maybe time to run on trains. The 19th century could no longer count on the Earth's easy turn: diurnal rhythms are no match for the rigorous deadlines of enterprise. Now we get time digitized: every second counts.

Crossing the Don on the Queen Street bridge, we get another take on time: a public art installation by Eldon Garnet. It takes us over the river, on past Broadview, under a railway overpass... all the way to Empire Avenue. It takes its time: less in tune with Standard Time than with the time, the rhythms, of the river.

|

|

Time: And a clock

Garnet's time piece spans the Don, & stretches along Queen beyond. His clock is analogue, not digital: its hands, like the Earth, move imperceptibly in the moment; we read them not logically but intuitively, time not fixed but flowing: "This river I step in is not the river I stand in."

Big letters sunk in the curve of sidewalk at each corner of Broadview read: "Distance = Velocity X Time"; "Time is Money, Money is Time"; "Too soon Free from Time"; & "Better Late than Never." (The business group sponsoring this work calls these "meditations on time.")

Beyond, banners catch breeze even when there is none: Coursing; Disappearing; Trembling; Returning (seen last heading west; we'll be heading east). A letter tops each pole, east to west: T I M E. It is one of the city's most subtly grounded pieces of public art. |

Planning these tours along Queen Street, I didn't imagine giving the Don one of its own; maybe a side trip from the tour west, or east. But, standing over the river one autumn afternoon (when I took most of these pictures), I realized it belongs not to River Street passed or Riverdale beyond: it is a boundary; a space between.

It doesn't even belong to Queen Street. Here ages before any street, the river is a place, and a force, very much its own. If not one easy to sense when you're on those streets or sailing along the Don Valley Parkway. Its force has been checked: by walls, by roads, by arcs of concrete ramp.

Unable to bury it in a sewer, as Toronto did so many other streams, the city simply swept over it -- long treating it like any other sewer, if open to the sky (and eye, even nose). But the Don rolls on, taking its time: it is still a river.

And a force: federal flood risk maps show the Don's blue line flanked by broad swaths of red; south of Dundas is a potential "flood damage centre" nearly a mile wide (the French caption maybe more telling: region sinistrée). The Don did flood in 1954, during Hurricane Hazel. Far west the Humber and Credit did too, 83 lives swept away in their watershed.

|

The river below

Stairs leading down from the bridge; life flowing on beneath.

|

To know the Don, you must go down to the river. That wasn't always easy to do, but now there's a stairway at the Queen Street bridge, and a few other bridges beyond. Step down and you're in another place: more relaxed than the street (though you can still hear streetcars); its time slower, its space more expansive if gently bounded, the river riding calm between banks bushed and treed.

It's not entirely bucolic. In places those banks are steel retaining walls, driven deep to hold the river to a course made by man -- here dead straight. In others, even mid-river, it's concrete -- footing massive pillars holding expressway ramps high overhead. It can feel awe-ful, mysterious, vaguely unsettling. Even a bit creepy. Or -- as beauty more fearsome than cute has been called -- sublime.

Ducks ripple the river; Canada Geese, in season, ripple more. They don't flee your presence but paddle up: they're urban fowl, the ducks anyway; like city squirrels they expect humans to toss treats. (I did: fair exchange for a picture.) Down here you can forget there's a city up there -- for a moment. Listen; look along the river to buildings, highway signs, bridges: it's there.

And you are still there. This, too, is the city.

And, I must admit, I haven't used those stairs often, an urban wanderer apt to ignore the valley (but for the view), traversing what can feel a flat cityscape -- even on streets sailing high over green earth and gleaming water below.

It is, very much, a Toronto thing: this is a city of ravines. As Bob Fulford said in Accidental City, "The ravines are to Toronto what canals are to Venice and hills are to San Francisco. ... There's nothing quite like them anywhere else. No other big city has so much nature woven with such intricate thoroughness through its urban fabric."

I have known a few ravines, some well enough to negotiate in the dark. You can tour David Balfour Park, carved by a tributary of the Don, in a memoir here; a link below leads to it. The wonders I found there (not counting those unintended by city fathers) were echoed by Anne Michaels in her 1996 novel Fugitive Pieces. I quoted from it there, and will again (reiterating a line above).

- "It is a city of ravines. Remnants of wilderness have been left behind. Through these great sunken gardens you can traverse the city beneath the streets, look up to the floating neighbourhoods, houses built in the treetops. ... Forgotten rivers, abandoned quarries, the remains of an Iroquois fortress. Public parks hazy with subtropical memory, a city built in the bowl of a prehistoric lake."

One park "hazy with subtropical memory" we passed on the previous tour: Allan Gardens, with its 1910 Palm House. Here on the Don at Queen, we're near the south end of one of those great sunken gardens. A walking trail -- beginning at the river's mouth, passing here on its west side, crossing to its east over a pedestrian bridge in Riverdale Park -- lets us "traverse the city beneath the streets" for a very long way, following the Don and its tributaries.

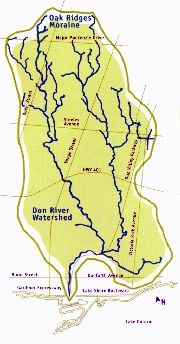

On one branch we could wander to Warden Woods and the St Clair Ravine, in Scarborough five miles east. On another Edwards Gardens, five miles north. Still farther north, if not connected, other trails run to the modern city limit at Steeles Avenue (five miles more). The Don goes beyond, through Thornhill, Elgin Mills, finally to its source; source too of the Rouge, far east: the Oak Ridges Moraine.

We won't, on this tour, go that far. But we will go quite a way back.

|

River's realm

The Don's watershed, from the Oak Ridges Moraine to Toronto Harbour.

|

|

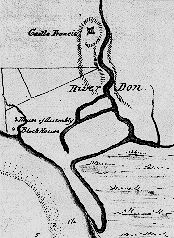

River Don, 1815

Meandering south via a vast marsh to the harbour. Angled lines mark future streets, Queen & King; Castle Frank (here Francis) is shown out of scale, south of its actual setting.

|

|

Canal Don, 1887

Meander from Bloor south to the marsh, overlayed with the line due to tame it. Neither canal nor many streets shown here were yet built -- but the future was firmly mapped.

|

The Don's southern watershed once lay deep beneath that prehistoric lake. Geologists have named it Iroquois, a vast inland sea stretching well beyond what are now lakes Erie and Ontario. The northwest rim of its bowl remains: a rise of land south of St Clair Avenue, marked by Davenport Road; to the east it loops north for a bit, taking in a stretch of Eglinton crossing what was once a bay.

The retreating glacier had dropped the Oak Ridges Moraine, its sand and gravel a natural aquifer; Iroquois's retreat to modern lake bounds left a sloping till plain of clay. Streams born north cut south through the plain, some running in valleys already carved wide by rushing meltwater. In 1788, when Alexander Aitkin first arrived to survey this land (his map of 1793 appears in "A line on a map"), he found many creeks running into the bay, flanked by wider rivers west and east.

He also found the Anishnawbe, settled along the river to the east. They called it Necheng qua kekonk. Or Niching qua kakinki. He didn't record what these names might have meant, but did put the first on a map. The Seneca, living farther east on the Rouge, likely knew this river too -- but, speaking a different language, likely called it something else.

Elizabeth Simcoe, wife of founder John, knew the river well, off on jaunts from Castle Frank. She heard another name: Wonscoteonoch. (Also recorded as Won scote on ach; orthography can be confounded by terms native people only spoke: we still see both "Anishnawbe" and "Anishnabe"; "Ojibwa" and "Ojibway.") She'd been told it meant black burnt land. Perhaps a recent name: early Anglo settlers often clear land by torching trees and bush wholesale.

Husband John, notorious for his "abhorrence of Indian names," would have none of it. Elizabeth wrote in her journal, August 11, 1793: "This evening we went to see a creek to be called the river Don." After the Don in Yorkshire, maybe on Milton's lead in a Yorkshire line: "Utmost Tweed or Ouse, or gulphy Don." (To an ancient tribe of the Caucasus, "don" meant... river. Who knew?)

In any case the Don it was, and remains -- if hardly as the Anishnawbe, Aitkin, or the Simcoes found it. Its meander south ran not straight to the harbour but branched: a map of 1883 still shows "Mouths of the River Don." Much of it filtred through a marsh stretching more than two square miles, rich with wildlife. Henry Scadding (historian son of John, an early settler on the Don) wrote of it in Toronto of Old, 1873:

- "In the summer this marsh was one vast jungle of tall flags and reeds, where would be found the conical huts of the muskrat, and where would be heard at certain seasons the peculiar gulp of the Bittern. ... The blue Iris grew plentifully, and reeds, frequented by the marsh hen, and the bullrush with its long cat-tails, sheathed in chestnut-coloured felt, and pointing upwards like toy sky-rockets ready to be shot off."

There were many rare birds, eagles of two species. And rare plants: Mrs Simcoe noted "tryliums, which resemble lilies," and toothache plant: "It has a pungent taste; Licorice." She reported on one river walk "the track of wolves, and the head and hoofs of a deer." On July 14, 1796:

- "-- saw millions of the yellow and black butterflies, New York swallow tails and heaps of their wings lying about. Gathered wild gooseberries and when they are stewed found them excellent sauce for salmon."

The Don was famous for salmon. Then.

It was also famed for floods, its marsh as "malarial." Many mills were built up the river for wood, grist, small manufactures; brickworks tapped its clay. Peter Lamb's glue and blacking factory on the Don at Amelia Street 40 years from 1848 was, as Patricia McHugh writes, "virtually an animal crematory." Living livestock added excreta to the runoff; Rosedale did too.

And the Don's lazy bends, its wide flood plain, lay in the path of progress -- ever marked in this town by straight lines. Cartesian order came first on paper: a map of 1887 shows the sinuous stream overlaid by a line unerring from Amelia south to Queen, a slight bend taking it to the river's west turn toward the harbour. An 1888 map shows just that line, marked "canal" -- anticipating achievement yet to come (map makers often do): the work wasn't finished for some years.

Its meander through the marsh was later confined to Keating Channel, turned 90 degrees to dump the Don straight into the harbour, its many mouths become one. The vast wetland it had nourished would be subject to development plans (as we'll see on a tour of its namesake neighbourhood, Ashbridge's Bay), for years none realized. The great naturalist Ernest Thompson Seaton would write of it:

- "This wonderful bird paradise is, alas, a thing of the past. It was turned into a city dumping ground, and when I last saw it in 1936 it was nothing but a level waste of garbage, tin cans, and ashes -- a sad commentary on the white man's civilization."

The Don Valley would see feats of engineering less mundane than the canal; even, to some eyes, touched by the sublime. Talk of spanning its wide reach at Bloor, where the river ran wild (and still does), had begun in 1880; a bridge was begun by 1915. And no mean bridge it is.

The first big commission of Public Works Commissioner Roland Caldwell Harris (we'll see another, even bigger, at Queen's east end), built mainly by immigrants, most Italian or Macedonian working shifts day and night for Dominion Bridge, it was christened the Prince Edward Viaduct.

It's more often called the Bloor Viaduct, carrying that street east from Parliament, over an arch spanning the Rosedale Ravine, over four more anchored in massive concrete piers marching across the valley, to Danforth Avenue -- nearly a kilometre in all, most of it suspended in mid-air.

As are thousands who, every day, see its black steel superstructure -- from the inside, on subway trains. Thousands more see it from beneath, driving the Don Valley Parkway.

|

|

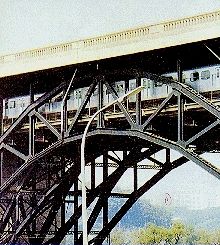

Spanning the valley

"The bridge goes up in a dream. It will link the east end with the centre of the city. It will carry traffic, water, and electricity across the Don Valley. It will carry trains that have not even been invented yet."

The Prince Edward Viaduct, built 1915-1918 (above, 1916) under the hand of R C Harris, czar of public works. Its piers sink 50 feet into the Don's bed, rising some three times that over its flow. The first subway trains zipped through in 1966, on decks built 50 years before. |

The Viaduct is among the city's most famed views. And most infamous: the long fall to the valley's floor has claimed 300 lives since 1918, many in the last few years; it is second only to the Golden Gate Bridge as a choice spot for suicide. A barrier is in the works -- paid for by a private firm wanting in return the right to make the viaduct a billboard. That's off: they'll get billboards elsewhere on the Parkway (its first); we're told we'll get a "luminous veil." We'll see.

|

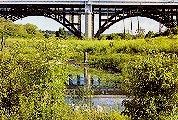

Valley view

Looking northwest from Riverdale Park: the Viaduct spanning the Parkway. |

The valley's biggest human work also offers interesting views. And risks. Opened from the lakeshore's Gardiner Expressway in 1964, finished to Highway 401 far north two years later, the 50 million dollar Don Valley Parkway was born, it's been said, "at the height of postwar automania... a gas sniffing high from which we're still coming down with a thump."

That line is from Leon Whiteson and S R Gage's The Liveable City, a 1982 look at Toronto's neighbourhoods. The Parkway, they admitted, is not one. It's a movie: "Metro's most cinematic freeway" -- its rises, falls, and sweeping curves offering widescreen (well, windscreen) VistaVisions of the city, especially on drives down from the north.

- "The screen speeding south frames a distant shot of downtown.... The tiny needle of the CN Tower sparkles in the sun. Light strikes the far lake out of a broad china-blue heaven Cecil B. DeMille might have ordered from his set designer. ... In your rearview mini-screen mirror is the corporate park of Wynford Drive, with its low temples to Bell and Shell.... The chimney of a brickworks and a paper mill pop up at racing road level like brick periscopes from the underworld."

Beyond the Viaduct the river gets a close up, then a crane shot from ramps down to the Gardiner, or into the city. "The widescreen epic fades out into the distracting detail of downtown. Streets, shopfronts, faces, traffic lights come into busy focus" -- details lost at 100 kph. Their script ends: "This is real life. The movie's over."

It was brought to us in part by E P Taylor, developer of what John Sewell called "Canada's first corporate suburb," Don Mills, born 1952. By the next year E P had secured the City's promise to run, in time, a highway from downtown to his doors.

|

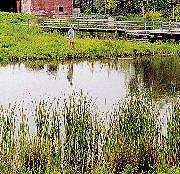

The Don reclaimed

Pedestrian bridge, with stairs to the river, in Riverdale Park. Chester Springs Marsh, reborn south of the Viaduct; a wetland revived at the brickworks off Pottery Rd. Farther north: heron, foxes -- & ubiquitous raccoons.

|

The valley has long been a route of transportation: on the river, trails, roads, railways, then the Parkway. It is also a route of energy: tall pylons on its west bank carry power to the city; pipelines beneath its east, oil and natural gas. Toronto, naturally, put the place to work -- then turned its back, Bob Fulford says "in shame: buildings put up on the river didn't even have windows looking out onto it," the city "trying to ignore its most important river."

Not everyone ignored it. Charles Sauriol, born 1904, trekked the river for two decades, beginning in 1935 -- like Elizabeth Simcoe making notes. They became books on the Don, my source for many tales here, hers included.

He was not alone in his stewardship: in 1991, citizens organized two years before as the Task Force to Bring Back the Don issued a report on how that task might be achieved. The next year saw another: Regeneration, work of a royal commission on the waterfront, headed by former mayor David Crombie.

It noted that access to the river was "limited and uninviting, and only a few hardy souls walk or cycle along it." That's what got us the stairway down from the Queen Street bridge (in fact replacing an earlier one, leading to the Don Station on the Belt Line, an early commuter rail service: the river was the eastern edge of its circular route). We also got stairs from the pedestrian overpass in Riverdale Park, four other access points north and south, and a riverside bike trail from Pottery Road down to Lake Shore Boulevard.

Souls less hardy than Sauriol now trek the river -- some with considerable energy. Task force volunteers have planted more than 40,000 native trees and shrubs. (A hillside in Riverdale Park I once knew as bare is now forest, young but dense with undergrowth -- already laced with paths carved by unofficial use: you can see it to the right in the Parkway photo above.) They revived Chester Springs Marsh, three hectares south of the Viaduct; restored wetlands at the Don Valley Brickworks.

|

|

Bringing back the Don The Task Force to Bring Back the Don (its logo top left) not only plants but plans. Above: a proposal to release the river from its confines south of Queen, restoring wetland habitat &, like all wetlands, filtering impurities & checking floods. |

The Don is indeed, if gradually, being brought back, with it much of its life. Great blue heron, if not gulping bittern, can be found on its northern reaches; foxes if not wolves. There are 18 fish species -- down from 33, but among them, again, are salmon. Raccoons never left, scavengers adapted to urban life, 100,000 said to live in the city. They prowl the streets by night, especially near ravines; even downtown, I've known them to drop in for dinner.

Ashbridge's Marsh may come back, in part and in time. In the meantime its life has begun to already -- on the Leslie Street Spit, long arms of fill run out into the lake. Born barren, they have been colonized over time by rabbits, rats, skunks, mink, even a few coyote. More than 400 native plant species have found shelter, 290 kinds of birds, among them black crested night heron, cormorants, and ring-billed gulls -- their rookery, we're told, the biggest anywhere.

Life has ways of taking root. Almost anywhere.

The life of the river depends, now, on people. The Don is Canada's most urban stream: more than 800,000 of us live in its watershed; its well-being rests in our hands. And, where the Don first springs from the ground, under our feet.

The Oak Ridges Moraine lies beneath the booming suburban belt known, by its area code, as 905. Politically it's known as Tory Blue -- apt to bow before the gods of progress and profit hungry to "develop" the land. But some there know the land they stand on, the stream it springs and the consequences, there and downstream, of rapacious and unfettered sprawl.

The provincial Tory government recently promised to protect the Moraine. But, as one environmentalist has said: "It's not really a conservation bill at all. It's more of a political tactic." An election looms: tree-huggers (well-heeled ones anyway) must be mollified -- if without unduly upsetting corporate backers.

Developers have not been fettered but bribed: offered public land elsewhere, worth hundreds of millions but theirs for the taking if they promise to spare the Moraine. For now. The bill includes a clause allowing the minister to revoke its terms -- by regulation, not legislation; at his discretion and without consultation. Any time.

As ever: in time we, and the river, will see.

See more on:

Alexander Aitkin's surveys in A line on a map.

Toronto as a city of ravines (in particular the natural and "unnatural" pleasures of David Balfour & Riverdale parks), in Promiscuous Affections, 1975.

Don Mills gets play in Diva Diaries.

Sources (& images) for this page: Charles Sauriol: Remembering the Don, Consolidated Amethyst Communications, 1981; & Pioneers of the Don (self-published), 1995. Heather Hatch, James Fraser & David Stickney: The Architecture of Public Works: R.C. Harris Commissioner, 1912-1945, City of Toronto Archives, 1982. Leon Whiteson & S R Gage: The Liveable City: The Architecture & Neighbourhoods of Toronto, Mosaic Press, 1982. John Sewell: The Shape of the City: Toronto Struggles with Modern Planning, University of Toronto Press, 1993. Anne Michaels: Fugitive Pieces, McClelland & Stewart, 1996. Michael Ondaatje: In the Skin of a Lion, Vintage Canada, 1996. John Barber: "Oak Ridges protection bill written in sand" in The Globe & Mail, Nov 17, 2001. Toronto Reference Library, & Urban Affairs Library: Map collections. Task Force to Bring Back the Don (Prince Edward Viaduct 1916, the Don's watershed, Riverdale Park's foot bridge, Chester Springs Marsh, Don Valley Brickworks, heron, planters, Don Mouth plan, & logo; from undated brochures).

Online:

Task Force to Bring Back the Don

http://www.city.toronto.on.ca/don

Toronto & Region Conservation Authority: Tommy Thompson Park (on the Leslie Street Spit)

http://www.trca.on.ca/ttp.html

Go on to:

Landscapes lost, & found

Garrison Creek; downtown's other streams & ravines:

reclaiming the life beneath our feet

Or go back to:

Passing stories

Queen Street Preview / Introduction

Or to: My home page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/queen/2pdon.htm

December 2001 / Last revised: November 13, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com