|

On the Origins of

TheBODY POLITIC Chapter 5

|

|

Minutes (Hours; years...)

Early collective ponderings:

|

It wasn't always efficient -- but it was effective: it kept people involved; kept them working out of no more than passion. Messy collectivity kept The Body Politic alive for more than 15 years.

Beyond

From 1974

The Body Politic's first three years saw not only key people who would go on for years, but distinctive ways of working together that would go on too -- in substance, if ever evolving in detail.

The collective met every week, sometimes on weekends but in time on Mondays at 8 pm, a regular date for all (including me from 1977) well into the 1980s. For ages the collective made every decision of any consequence, even a few that might seem inconsequential: there was once considerable debate over whether to rent a post office box, at all of $60 a year. For some years every story was still read aloud at meetings, for approval, revision, or rejection.

Minutes from the first few years show formal motions and votes -- some overturning earlier motions of the same meeting. In time decisions were made by consensus, often taking rather a while to achieve. If not achieved, then (in my time only then) would we resort to votes. Or not: some things simply got talked into the ground, as minutes of April 1, 1974 attest:

- A discussion of the content and philosophy or direction of The B.P. with regard to literary, political and news content occupied the remainder of the meeting. No decisions were reached.

It could be a cumbersome way to run a paper. But it was not just a paper. It was never meant to be. It was a political project, not just in product but in process. Born when collectives were common, The Body Politic's survived into the Age of Reagan and the rage for "efficiency."

It wasn't always efficient -- but it was effective: it kept people involved, committed; kept them working out of no more than passion. Hundreds of people over time, only a handful ever paid, and if paid meant to give it their lives. Without that passion -- and ways to foster it -- there would have been no Beep.

Soon the collective couldn't possibly make every decision, so it spun off little collectives. We called them working groups, the first coalescing around (as leftists like to say) reviews. In 1976 Ed Jackson pulled them into a distinct entity called Our Image, so distinct it was often its own pullout section. (One activist news addict said he liked that: he could pull it out and throw it away.) Ed got others involved, making the Our Image Working Group a skilled, coherent -- and in time independently strong willed -- editorial team.

Then came the Canadian News Working Group. Tim McCaskell, alone at first, handled the rest of the world (US readers sometimes surprised to find themselves just one part of it). By 1980 there was a Features Group, if feeble: in 1981 it merged with Our Image, that name abandoned, becoming Features and Reviews. In the masthead anyway; in house we called it Midmag, responsible for the middle of the mag.

There was even an Office Administration Working Group. And responsible these groups were, mini collectives working much like the main one -- and autonomous of it. Most of the time. They'd be checked if they wandered, but only after they had. Sometimes long after: in 1981 Our Image was pulled back from two years of academic drift only by a messy collective showdown and what, to some eyes, seemed a purge. We never did learn well how to get rid of anyone.

Those groups had meetings of their own, so many that by mid 1983, when many of their members joined the collective proper, that august body took to meeting just once a month. For a while. The arrangement soon broke down, many seeing they had little more influence as collective members than in their own nearly independent working groups. Some key players around for years never joined the collective, even when invited. After all, who needed another meeting?

As Ocsar Wilde said: The trouble with socialism is that it takes so many meetings. Or did he say evenings? Well, either way: most people were free to meet only on evenings or weekends, having work in the real world. Not that you'd guess, given how much time they spent at the paper.

The working groups not only worked, but taught. And learned. The Body Politic became an activist academy, font of skills technical and political. For some years we even held off site seminars, the extended BP family assessing the issue just off the press. We called them post partums, more optimistic than post mortems.

It was messy collectivity that kept the paper vital, growing, alive.

No one owned it. Touring recruits around I loved saying that: No one owns any of this; our work lines no one's pockets. A noble ideal, if one with potential risks. Other gay papers born vaguely owned had ended up personal property, their proprietors selling out and walking away, their pockets stuffed with the fruit of others' labour.

To prevent that The Body Politic created an owner: Pink Triangle Press, founded in 1975 as a not- for- profit company in which no one could hold shares. That meant, by law, a formal board of directors -- the first hint of hierarchy. (Even among paid staff there was none: no one person "in charge," all paid the same meagre salary.)

But in practice the board had no impact: the collective was still in charge, its members passing directorships around as if no more than party hats. In 1978 they might well have turned convicts' caps, the Press charged with publishing naughty bits, in law those directors liable.

In September 1986, The Body Politic at the edge of its grave, the Press all but bankrupt, we'd seek rescue in hierarchy. Ken Popert was appointed interim publisher, to pull things back from the brink.

Within months it was not interim, TBP dead, the Press kept alive by its spunky offspring Xtra, distributed free -- Ken its publisher and editor. The collective was a relic of history, a lame duck put to rest in December 1987, a year after it killed off its founding creation.

Still, not a bad run in business for an "inefficient," airy fairy concept of the early '70s. (Or, truly in spirit, The Sixties.) The board went on, as did Ken and the Press, to this day still not for profit -- if often for no little "excess revenue."

|

Advertising (& its discontents)

Homo promo:

|

TBP was born without ads; maybe didn't even want any. Xtra would depend on them for its life.

Ads caused endless contention. Battles over two, one a mere classified, would be the beginning of the end of The Body Politic.

Red Hot porn; race & sex

For details on fractious ad battles see Promiscuous Affections, in particular the Red Hot Video flap in 1983: Jan - Sept and the black houseboy classified debate in 1985: Jan - Jun.

Xtra's revue came entirely from ads, until its chat and classified phone lines were invented by Colin Brownlee in 1990. To this day those services make most of the Press's money. In 1999 they cleared $1.2 million in (not- for- profit) profit.

The Toronto, Ottawa and Vancouver Xtras lost among them more than half a million dollars that year. Not for want of trying: some 60 percent of their pages were awash in advertising.

There is no little irony here. The Body Politic began with no commericial ads -- and not wanting any. Maybe: at the bottom of Issue 2's Community Page there was a box about two inches square headed: "ADVERTISING [three times] -- Any business interested, please call." There were no takers right away. By Issue 4 there were, six (only two paid) all grouped on a single half page. And there was this, on the editorial page:

-

Our readers will note that for the first time, this issue contains advertisements from commercial enterprises. After much discussion, the collective has decided to accept ads, exercising control over them by using the same procedures as in considering other submissions.

We shall not accept ads we consider representative of businesses which promote sexism, or whose ads are expolitative in appearance. It is hoped that with the funds available through advertising, The Body Politic may soon be able to publish on a more frequent schedule.

(An example, by the way, of early house style: "shall" for will; "which" for that; "It is hoped"; passive constructions abound. It was important to sound important.)

One of the first paid ads was for Momma Cooper's, the day's incarnation (of many) of a dance club over The Parkside. Momma was gone after Issue 5; The Parkside itself never showed up at all. Few bars did, most straight owned, hardly interested in helping The Body Politic haunt their halls "on a more frequent schedule."

The first nominally gay businesses to run ads were baths. The Club made its début (in the paper and in town) in 1973; the Romans, perhaps smelling competition, in 1974; by 1975 The Barracks. Even when there were gay owned gay bars, they were often slow to advertise. In 1977 Dudes ran an ad announcing its opening, one of the few that ever did; Buddy's, launched the next year, didn't show up in TBP until 1980.

Many ads were from businesses gay owned if not gay in name: a pet shop, a restaurant, a hairdresser; boutiques for cloths, plants, personal grooming and housewares; travel agents; a few theatres and the occasional publisher, usually in league with Glad Day. For years, such small (if loyal) accounts were the bulk of it.

What bulk there was. Minutes show ad revenue for the March / April 1974 issue at $399.10 -- that for taking up just under 10 percent of the paper's 28 pages. It would brush 20 percent just a few times in TBP's first five years. With Issue 100, January 1984, it pushed 40 percent -- too much we said, and from there held it in check, urging more advertisers into Xtra.

It would take to the mid 1980s for The Body Politic to look like what most people think of as a gay mag: full of bars, beef, and poppers. In all its 15 years the paper saw very few big corporate ads, mostly for booze and none for long.

Not that we made it easy. All of us hated ad sales, even if few paid staff escaped a stint pounding the pavement for business. That is, on top of all the other work we'd much rather do.

No one would do sales full time until the summer of 1987, when Colin Brownlee burst on the scene with an entrepreneurial gusto nearly nervous making to old hands -- if much appreciated for its effects: Xtra owed its survival to Colin, as did Pink Triangle Press. But The Body Politic had died with that year's February issue.

Even when we found willing advertisers, they would sometimes find we weren't willing to run their ads. That 1974 edict on ads "exploitative in appearance" was liberally applied. Or rather, not so liberally.

Hairdresser Robert Gage (confidante to high society) ran ads just to show support: he was a friend of Gary Ostrom's. One ran without its intended image: a chic coif deemed "offensive to women." So we assumed: at the time there were no women on the collective.

Queen Street restaurateur Greg Couillard was once utterly baffled when we rejected an ad for The Parrot, one of our most constant contracts. It was a comic strip, a play on Cole Porter's "Miss Otis Regrets (she's unable to lunch today)." It had a gun in it: violence against women. We didn't get the reference: it was Miss Otis who "drew a gun and shot her lover down." One might wonder that we never wondered about The Cow Café.

But it was images of men, not women, that causeed most fuss. In 1978 we showed an ad we had rejected (by a tie vote, along with a 10 issue contract) as "stereotypical," "sexist" -- it might offend women. Gay male feminists were ever willing to wield guilt by proxy.

Some simply said (the height of analysis) that the ad was "tacky." "Do we want to fill the paper with tacky ads?" By the standards applied to that 1978 Club Ottawa ad (above), we later would.

We could be just as picky about classified ads. They weren't an issue at the beginning: there were no classifieds. The first showed up in Number 5, summer 1972 -- unsolicited: "Young man has central apartment to share." It took two more issues to offer an order form.

Soon with it were warnings, some legal. We had no problem with group sex or people under 21, but the Criminal Code did. Still, we had our own codicils, if trying to be nice about them:

- If you're interested in meeting people it's best to be positive. Tell them about yourself and your interests -- not about what you don't like. Specifying exclusions on the basis of race or appearance (saying "no fats or fems" for instance) is just plain rude, and being rude doesn't make friends.

"No fats, no fems" -- no ad. "Straight looking, straight acting" we could accept (if with a wince at self oppression). In 1985 a man would say clearly what he liked: "Black Male Wanted: Handsome, successful GWM would like young, well built BM for houseboy."

Houseboy? Images (or the potential reality?) of servitude caused much stir. But he'd said yes to black men, not no, so we ran it. Once. It might have run again but for a much bigger stir, in which we'd be called racists.

We had often been called sexist, two years before in a case quite specific. Accepting an ad for a video company said to sell snuff films (a rumour unconfirmed, if so strong it got three of their Vancouver outlets bombed), we stood charged of promoting violence against women.

Those two battles threw pornography, censorship and race into one pot, brought it to a boil -- and dumped it on our heads. They marked the end of collective solidarity, and helped lead to the end of The Body Politic itself.

And all over advertising.

From its birth The Body Politic was more than a local rag.

It would often be pressed to be more local -- & less. We were ever charged with "Torontocentrism."

For years, most money came as originally intended from sales -- TBP hawked by hand at first, then on newsstands. The paper ran a list of outlets as early as Issue 4: 20 in Toronto; nine in other Canadian cities; six in the US; one in the UK. Two issues later another list showed The Beep in 80 locations. There would be many more, if few easily secured.

The most solid base of sales, and support, were subscribers. Again, not that the paper made it easy at first. Issue 2 was the first to offer the option: six issues for $2. Only in Issue 4 was there a form to fill out and mail in.

March / April 1974 was the first issue to actively push subs, a back cover ad urging readers to "Move with the masses!" (a parade of queens, literally, with crowns and a little dog if not, it seems, a Corgi). It took until 1976 to promote renewals, actually sending out notices. Before that there had been just a note in the paper telling people how to find the expiry date on their mailing labels.

Subscription promo in TBP's pages did get bigger (and more zany). In time about 3,000 people were signed up, not many as such things go. But, rare for a little Canadian mag, more than a third were outside Canada -- as many as there were in Toronto.

The Body Politic, nearly from its birth, was more than a local rag. It had to be: born of a movement spanning the country, even much of the world, its outlook was obliged to be national at least, even, as best it could, international.

Over its life TBP would have more than 80 regular correspondents in 21 Canadian cities, occasional ones in Europe, Australia, New Zealand, the UK and the USA -- all of them activists in their own locales and, of course, working for free.

By the late '70s more than a third of its writers -- not just reporters but essayists, reviewers, even columnists -- lived outside Toronto. We would see years of pressure, especially when it came to news, to be more local. And less: "Torontocentricity" was a perennial charge -- as ever in any Canadian venture run from its Anglo metropolis.

At least we had the sense not to claim bilingualism. It was briefly bruited, but only a piece or two ever ran in French. There were, at least in language, limits to our "national" hubris.

|

Deadlines (& more deadlines)

"Now monthly":

Really monthly:

|

|

Making trouble (Just part of the job)

Naughty bits:

|

TBP's trials

For links to more details, see entries on the Contents page of Promiscuous Affections from 1977 to 1985.

PTP after TBP

I was briefly back at Pink Triangle Press years after The Body Politic was dead -- in spirit as well as fact. See 1994, Part 2 and 1995, Part 1 in Promiscuous Affections.

The Body Politic began as a bimonthly, at least in aspiration. From 1974 it was one, securely -- and then decided that wasn't enough. With the September 1976 issue the paper went "monthly" -- in fact meaning 10 issues a year.

Twice each year, summer and winter, we did doubles, so got a break from the production grind. We used those breaks to talk: assessing issues past, brainstorming those to come; setting directions. It was then we'd ask (again and again): What's it for? What do we mean to do? And are we doing it?

In time, those two oportunities to ask such questions in relative calm would become none. The July / August 1984 issue was the last double. From there on they really were monthly, 12 issues a year. Twelve deadlines a year; counting Xtra (then "biweekly" at 24 issues a year), it got up to 36.

This pace, set largely by commercial pressures, left little time to sit down and figure out what our "basis of unity" might be now -- or even if we still had one. As founding visions drifted into history, increasingly unshared, to some even unknown; as the daily grind of "what" and "when" and "how" pushed out "why," our goal came to be the goal of any business: to stay in business. To keep running. To run faster.

To where? Why? In time, few could say. And even they weren't sure.

Our sense of shared purpose had crystallized most clearly under threat. The Body Politic often took risks and got into trouble -- no surprise for a radicial gay rag: you might say it went with the job.

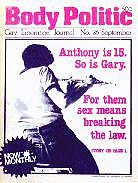

TBP's first brush was with the media, not the law. After Issue 5, where Gerald Hannon went on about "Men and little boys," the big dailies made quite a flap, one suggesting the police take a look at what the homos were doing in print.

They did, but didn't admit to it until 1975, when a comic strip showing a blowjob raised not a peep -- except from the morality squad. That issue got taken off the stands, if not quietly: the next one's cover showed a fellatious frame, censored.

But that was nothing to the six year saga that began December 30, 1977, with a raid on the paper after it ran Gerald's "Men loving boys loving men." In the midst of that we'd be busted again, for an article in the April 1982 issue on fistfucking.

We ever refused to be "respectable homosexuals" -- of which, even our critics claimed, there were a few. You can follow these trials in detail in Promiscuous Affections, from 1977 through 1985.

You'll see we won. Three times.

That "basis of unity" on which The Body Politic depended for its life had encompassed just a few folks in its early days. Over the course of its life, people would flock to it by the hundreds.

I once did a graph charting how many people were involved in each of the paper's 135 issues, how many for the first time. I included letter writers -- with cause: a letter to the editor was the toe in the water for more than 40 people who'd later jump deep in as Beepers. There were, in all, more than 2,000 of them. More than 500 took more than a few laps.

Many stayed for years, among them those key players who first showed up early on, their numbers then small: just eight of the 21 issues up to the end of 1975 involved more that 25 people as workers, writers, letter writers. But soon there were many more. By the end of 1976 nearly 60 people were working on each issue. By the end of 1977, more than 85.

The line on that graph bounced between 75 and 95 for the next three years. In early 1981 it soared to more than 100, a quarter of them appearing for the first time. No mystery in that: the February 5, 1981 baths raids -- or rather the massive resistance to them -- showed just how ready fags and dykes were to get out and demand a place in the world.

From mid 1982 to the end of 1985, only two issues would be the work of fewer than 100 people. The peak, in summer 1983, was over 130.

Never rich in cash, The Body Politic came to be replete with human wealth: scores of people we could count on all the time; the skills of those who'd been around for a while (most learning those skills there); the energy of those who'd just walked in the door or sent in their first tentative piece of writing.

Very few did it for money. Even those few who got paid (the most at one time eight, half part time) didn't do it for the money. You couldn't have paid them to do all that they did.

They did it, just as those first few did in 1971, for love. Their status came from what they could give away: to each other, to themselves, even to people they'd never meet.

People not yet even born. I know: by now I've met some.

Pink Triangle Press lives on. Its annual budget is well over $6,000,000. It has offices in six cities across Canada, publishing papers in three (and sucking up phoneline revenue all over). It employs more than 50 people.

Those few folks in 1971 could never have imagined it. Nor would they recognize it: not a collective effort but a "real world" bureaucracy; less a medium of social change than a media empire, its risks more financial than political; an enterprise less interested in "the growth of gay consciousness" than in promotion of a mythical -- and screamingly banal -- "gay market."

Nor could they imagine that anyone who does anything at the Press now does it for pay. The Press no longer needs labours of love: it's a business like any other, buying commitment (or so it assumes) with money.

But it's not rich. Not really. Not nearly so rich as The Body Politic was for so long. You'll find years of its story, from 1977, even before, and many of the people who made it rich, in Promiscuous Affections.

Go back to Introduction

Go to Promiscuous Affections: Intro or Contents page

Go back to my Home Page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/oldbeep/beyond.htm

January 2000 / Last revised: September 22, 2003

Rick Bébout © 2000-2002

rick@rbebout.com