|

Promiscuous |

|

Dramatic dynamics Gay theatre blooms

Homo / Hetero:

Homo / Homo / Porno:

|

With Andrew I felt a groupie; with Neil wary at first. I'd get both to write for TBP, Neil quite often.

Sky Gilbert

For this pioneering pervert playwright, founder of Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, (& his ongoing battles with "bourgeois sweater fags") see:

Diva Diaries

1985

January through June

- January 19, 1985, to Jane:

Another Saturday off after the long stretch of production nights. This was our first February issue, having in the past been able to allow holiday distractions to flow into January [we'd just gone from 10 issues a year to 12], and there was a sense of having to scrape to get enough material together.

Bob Wallace's piece came to the rescue and I had a good time working on it, mostly because I liked the images. During almost all those production nights, Andrew Alty and Howard Lester (see page 33) were no more than 20 feet away, through two walls and one floor down on the stage of Theatre Passe Muraille next door.

Their show, quite good, has been sold out almost every night, and I've had a chance to talk with Andrew a few times, by phone getting facts for the article, and once when I popped over around midnight for an after show party at the theatre.

He's a sweetie and I feel a bit of a groupie.

Andrew Alty and Howard Lester were in town from London with their new show, The Go Go Boys. They played -- and in fact were -- a gay man and a straight man, good friends sometimes forced to test that dynamic. It was zany. Andrew later told me the title was partly inspired by The Manatee; he'd been to Toronto before but we'd never met.

Also in town from London was Neil Bartlett. He had been here before too, in January 1983, touring with a British troupe -- mixed gay, straight, male, female -- doing Bertholt Brecht's In the Jungle of Cities. I never saw that and hadn't met Neil. This time I did, and did see his show: Pornography: A Spectacle.

Bob Wallace -- playwright, editor of The Canadian Theatre Review, late '70s stage critic for TBP and an occasional writer since -- had done a big piece on these two recent shows and more generally about "the blossoming of theatre by and for gay men." It ended with a note promising a future discussion, and "an in depth look at the work of Sky Gilbert," Toronto's most in your face thespian.

Neither piece was published (we'd see much more of Sky in any case) but that discussion did happen, taped at TBP February 2. Bob, Neil, and Andrew were there, as was John Palmer, director of Brad Fraser's first big hit, Wolfboy. It had been at Passe Muraille in early 1984, giving most of us our first look at Keanu Reeves. (Roger Spalding had seen him already, Keanu one of his alternative school students).

I was in on that talk, too, if bringing experience in things other than theatre.

- February 16, 1985, to Jane:

A few nights ago I was at Chaps, and had sat at a table over which there was a leak in the roof (I found out when I got dripped on). I moved, and a few minutes later looked up to see someone else sitting in the same seat -- not just anyone, but a man I've been gazing at for months: trim, quiet, very sexy, always apparently quite unapproachable.

I didn't premeditate what I did or anticipate any response -- I simply walked up behind him, put my hand on his shoulder and said, "If you sit here you're going to get wet." In retrospect I imagined he might simply have grunted and moved on; isn't that what beautiful men in gay bars are like?

But he stood up and smiled and moved back to the table where I was sitting. His name was Frank; he'd moved here from Halifax a year ago. When I mentioned having seen him often with a dark haired, bearded man, he rolled his eyes and said, "He's the reason I moved here. We've been together three years and it should have been over two years ago and it's just getting over now. Tonight, sort of."

Within five minutes this remote, sexy, taciturn vision had become a hesitant, vulnerable man telling me things very painful for him. I told Andrew Alty about this at lunch today, reflecting on the one bar scene in his play, portraying a gay bar as these things usually do -- cold, unfeeling, mechanical. Andrew liked my story and said he had been trying to deal with the environment, which can be all those things, not the people in it.

But it was too easy to misread, not only in a way that fulfills straight stereotypes of the sad gay life, but that feeds gay self pity and self loathing; an indictment not of a potentially alienating institution but of its miserably deficient, selfish inhabitants. This is not most gay men I know, not even most of the ones I've known only for minutes or hours at a time.

Andrew knows this. One of the lines in his play, and one that got nailed by people for reinforcing a conflicting yet coexisting straight stereotype of gay men, was: "I'm not promiscuous! I'm just... lonely."

When he had heard that line in Andrew's play, Neil Bartlett said, he wanted to stand up and say: "I am promiscuous. And I'm not lonely." Andrew Alty got a lot of flak there: for winning "mainstream" success by appealing to "bourgeois" gay men.

It wasn't the first time at the paper that I'd heard articulated that middle class leftist death wish: success is failure; honourable defeat is holy. What irked me most, I told Jane, was:

- the dismissal of all those Franks in all those bars as "bourgeois," as someone whose experience doesn't count. Neil at one point, talking about handing out flyers for his play at the door of Chaps, said he didn't know why he wanted these people to come see his play -- but that he did, because it was about what went on in bars like that.

"Bourgeois clone" Frank works as a hotel clerk, has never been unfaithful to his messy lover, and laughed incredulously when I said that this must have been despite lots of offers: he's very attractive.

I was rather down on Neil Bartlett that day, mostly in defence of the accused. Andrew was bouncy, vibrant, smart, terribly cute; we'd partied; we'd had lunch -- I had a crush on him (who wouldn't?).

Neil I'd not met before; he struck me as severe, at first almost scary. But even in this letter I admitted to Jane that I shouldn't be so snippy about him.

- Pornography is quite wonderful, outrageous, intentionally shocking -- but with real human beings stepping through the sensationalism at regular intervals to speak between the screams of cliché in normal conversational tones about who they are and how they really feel. The recurrent theme is one of intense pornographic description, which the actors suddenly stop, pause, and say, "of course that was merely a quotation," or "but it really wasn't like that."

Neil had one particularly gripping monologue, describing violent sex with a man named Peter. The details were meant to shock, that shock a foil to the tenderness and vulnerability reached by the end of the scene: the two of them holding each other, sobbing, Neil wanting to say what he felt. But finding no words.

"There is only one man to whom I say 'I love you,'" Neil said. "It's not Peter. It's Chris, my lover." When "I love you" doesn't mean what it's supposed to mean -- marking a status, not a feeling -- "love" becomes the most taboo word. Next to that the most explicit, "shocking" sexual dialogue is, as the play said, "merely a quotation."

Dressed "not as a woman,

|

Most straight people wouldn't get it, many gay people too, afraid of exploring things about ourselves without having to make them acceptable or even comprehensible to anyone else.

"Confusion can be a very valuable tool, because when people are confused they are sometimes obliged to think."

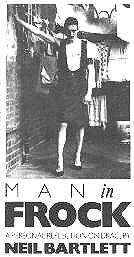

Andrew sent one piece; Neil went on to do big features. In March he wrote me about a British book, Men in Frocks. He wanted not only to review it but "to sketch my own involvement in drag, to say as simply as I can what I think it feels like." He ended: "I'm looking forward to us being pen pals (another name to add to that list of indefinable and unchristened forms of gay relationship)."

- April 7, 1985, to Neil:

Well, to the piece. As I said, and you said too, what it needs is a little more beef. The central misperception that has to be addressed is the one that John Palmer kept bringing up in our discussion in February: Why would you want to dress like a woman?

You were so clear then that that was not what you were doing. It's really about dress or decoration as a form of gay male expression. When you said so clearly : "I'm not dressing as a woman; I'm dressing as a gay man," it was like a burst of light.

Another angle is the one you were so clear about in Pornography: these things have to be seen from within gay culture. As in so many things, we borrow (or have forced on us) straight interpretations of gay phenomena, essentially becoming tourists in our own world rather than active players trying to comprehend our lives and our culture with a knowledge of what things mean to us, and why.

This was the risk Pornography ran: most straight people wouldn't understand, and many gay people wouldn't either, or would be afraid of the idea that we should explore things about ourselves without having to make them acceptable or even necessarily comprehensible to anybody else.

We were ever looking over our shoulders at The Body Politic, had been for years, wary of reactions. Not from the wider world: we didn't much care what heterosexual society thought of us -- though too many homosexuals did (and sadly, still do). That sort of obliviousness did sometimes land us in court, but that was just part of the job.

We glanced more often at other gay people. The ones who found us too radical -- they'd pop up after every Pride Day decrying all that leather and drag: is this any way to win respectability? acceptance? -- we mostly ignored. We knew that "respectability" and "acceptance" weren't the route to liberation.

We were more nervous under the gaze of those who'd say we weren't radical enough, weren't "politically correct" -- a term that began, in fact, among radicals as a joke on ourselves.

Neil, I would find, refused to look over his shoulder at all. He would not "explain" gay life -- even to other gay people. He never claimed to represent anyone but himself -- as one never should: it's condescending and you'll just get shit for doing it all wrong. He didn't care that people might not like what he did, might not "get it" right away. In time some would.

Neil's "Man in Frock" (Neil was that man), ran in the July 1985 issue. In it he quoted a line from the book: "My favourite sentence from Men in Frocks runs: 'Confusion can be a very valuable tool, because when people are confused they are sometimes obliged to think.' That goes up on my wall as a text for our times."

I quoted from the book, too, in a sidebar full of pictures of people in it, their stories, what they had to say. My favourite lines: "There are as many sexes as there are people"; "How do I define myself? I don't. I live it. It's me."

TBP had long been preoccupied with history, working to reclaim a past once unknown, even to preserve our stories for the future. That's what its own archives was about, started in 1973 and becoming the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives.

The paper had run features later made books: James Steakley's The Homosexual Emancipation Movement in Germany, 1860 to 1933, in TBP 1973-74, published in 1975 by Arno Press; and in 1978-79 John D'Emilio's series on the Mattachine Society, by 1983 part of his book Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970.

We'd not ignored the home front, in 1976 running Robert Burns's look at "Queer Doings" in the Toronto of 1838. There were many smaller history pieces too, the smallest mere paragraphs flagged "Once Upon a Time," each beginning "Five years ago," or 10.

In the June 1985 issue there was one with a lead more specific, and a photo.

- "Seven years, three months and fifteen days ago... more or less, the porn squad raided the offices of The Body Politic and carted off 12 boxes of material in response to the magazine's publication of an article called "Men Loving Boys Loving Men" in its 39th issue.

"On April 15, 1985, the police were back -- not to seize anything but to return the last of their 1977 haul.

"TBP staff members Sonja Mills and Gillian Rodgerson, pictured below going through the boxes with Gerald Hannon, were only 15 and 17 years old when the material was taken. For them, and for older staff, it was like opening a time capsule.

"None of the material was ever introduced as evidence in the long series of trials and appeals which, after six years, resulted in the magazine's full acquittal. Long time staff member Rick Bébout recalled that on the day the material was taken away he feared we'd never publish again. A few hours after signing the waybill for the cops' final special delivery, he took the 114th issue off to press."

That time capsule is still intact, as Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives Accession 85-001, Boxes 1 to 5. On the top of each box is a list of contents, handwritten by the police. That 114th issue, dated May, had been uneventful, in fact rather a lame duck -- for reasons I'll get to in a bit.

Some said we should flag the usual requests for "romantic dinners, long walks in the woods" -- "Warning! Fantasy!"

- "BLACK MALE WANTED: HANDSOME, SUCCESSFUL, GWM would like young, well built BM for houseboy. Ideal for student or young businessman. Some travelling and affection required. Reply with letter, photo, phone to..."

Thirty one words. That's the title we gave to that issue's biggest feature -- those few words having generated thousands. "An Internal Debate Goes Public," it said on the cover, as we ran scads of internal memos and letters from people in the community. That debate was a replay of our 1983 flap over "Race, moustaches and sexual prejudice." It would feature many of the same players, even some of the same lines -- "the inviolability of desire" chief among them.

It had begun when Philip Solanki, a South Asian man working in classifieds, first spotted the ad; he didn't like it and said so. But it didn't violate current policy -- which prohibited saying what one didn't want, like "no fats or femmes" -- and it had run. The debate now was whether to run it again.

It was no ordinary collective pondering. Gay Asians of Toronto, Lesbians of Colour, and a new Black gay group, Zami, were invited in for it. As that April issue reported, "The February 5 meeting did not go well." That, to be sure, was an understatement.

The ad did not run again. A new policy was set: "Personal ads offering scenarios that might reasonably be read as racially or otherwise abusive or stereotypical must clearly indicate that what is being requested is mutually consensual sexual play and not relations of genuine subservience, such as employment."

An editorial in the June 1985 issue further explained: "Ads which are clearly directed to fantasy alone would not be turned away." A good thing, that: some of us half wanted to mark the usual requests for "romantic dinners, long walks in the woods," etc with a flag -- "Warning! Fantasy!"

But only less saccharine proposals would now, in effect, force that codicil, advertisers expected to provide warnings of their own, neatly separating "safe" fantasies from life's messier realities.

Ken Popert found that distinction logically bankrupt. And craven to boot. He went on "intellectual strike," quitting the collective but not staff. That led to further flaps: staff members, once past probation, were supposed to be on the collective.

Ken survived but didn't rejoin the (officially) governing fold until late 1986, saying then that if this work was worth doing -- he doing a great deal of it by then -- it was worth the compromise.

I found Ken's stand (before the compromise) typical of his purist rationalism: he liked pursuing logic to the point of absurdity. "Sexual desire and fantasy is just there," he wrote in one of his memos, "like quasars or protons" -- hardly what you'd call a good social constructionist line. But I wasn't entirely unsympathetic.

- I have some problems with the "inviolability of desire." I don't think Ken is arguing that "inviolability" means "unquestionability," but I have too often seen "fantasy" put forward as the last word. Saying it just is, unchangeably, has too often been used as a way to end investigation. I want to ask: just is what? and why?

Still, Ken and I do agree that this is territory we should be in. Tim [McCaskell]'s response to Ken makes me feel that he thinks we shouldn't really be on this terrain at all if the things we find there are a threat to community solidarity.

I disagree with Tim's reduction of gay liberation to the building of a quasi ethnic "minority" community, with particular kinds of desire (pedophilia; "fantasy sex") neatly assigned to sub- minorities.

I think the exploration of sexuality as it is (and it's not neat) is one of our most fundamental jobs. Not the only one, certainly, but one only we can do from our particular perspective, one that no one else can do for us, and one that transcends even as it depends upon the creation, development and defence of our space, our zone of experience, our "community," if you like.

A letter in the next issue led off: "Congratulations! At last we know how large a horde of politically correct dilettante gay pseudo-intellectuals can dance on the head of a pin!"

But that dance wasn't a pinpoint pirouette; it was a stomp in the muck of real life -- and real sex. It was vital. It was, I believed, the very thing for which gay people (or, as now more accurately put, queer people) would be remembered, opening up questions that in time would reshape history.

Years later I still think it's vital -- but I'm less sure we'll be remembered for that dance of ideas. Too many of us have given it up. The "houseboy" debate sped that surrender, leading to the ruin of a forum once home to much hard and messy thought: The Body Politic itself.

Dale would soon be hired, first as assistant to the new production coordinator, then as equal in the job. His partner over the layout boards was one of the few people ever hired off the street rather than from inside (though in a way I had been, too). Robyn Budd was a dynamic little redhead dyke. In real life she was an artist; she'd later call herself Robyn Lake.

Robyn and I set to a task assigned months before: redesigning The Body Politic. As with Xtra, initial plans had been grand, the final execution more modest. TBP got a new logo (my design and a bad one), a new section (Coming, a nationwide events listing, Out in the City having gone to Xtra; Coming would flop the next year), and a new, more open layout.

Too open. I didn't have the wisdom Kirk Kelly did in 1975: the format was too easy to play with; within months it would be a mess. The only positive change was in the paper's subtitle: "A magazine for lesbian / gay liberation" -- just as it had always claimed, but that line had never said "lesbian" before.

Issue 114 was the last of Kirk's old look, a lame duck number as I said (if, alas, better looking than its hatchling would become). The June 1985 issue launched with its huge, new boxy logo and a cover feature, by David Vereschagin, on General Idea.

Robyn and I got on well, but it's not for nothing I alluded to her "real life." She had a life outside the paper, as so many of us did not; in time that life would no longer accommodate the mad pace of The Beep. She'd leave the job by March 1986 but not unhappily, sticking around to write from time to time.

Dale stayed longer. He was young, tall and thin, wonderfully quirky. Once on his way to dinner with me he bought a pair of pyjamas and, not wanting to carry them on his bike, put them on, the bottoms under his pants, the top as his shirt. No one was phased, least of all Dale. I was shepherding both him and Robyn into their new roles -- if, for each, with somewhat different dynamics.

- June 14, 1985, to Jane:

Dale is seen as one of my protégés. (Curiously coloured word, that: a "protected one"? Craig Patterson manages to make it sound vaguely dirty.) Dale may have my "protection" to some extent, but what he mostly has is my trust and affection.

On Wednesday night, about 12 hours after he and Robyn had finished the latest Xtra, I saw him wandering a little unsteadily through the crowd at Chaps, having drunk too much. I found him and we held onto each other for a while at the edge of the dance floor. "It's sort of like being in your own living room," he said, which is exactly what the bar can be like at the best of times.

We do this with each other a lot, over the layout boards, at the typesetter, on bar stools and at dance floors like that one. I've asked him home once or twice and he's able to say no in a breezy and matter of fact way that always leaves this affection intact, still possible, still enjoyed.

His independence and strength are reassuring to me. I know that if Robyn were to find the job too much (and she yet might: she does it diligently but resists it more), Dale could provide the continuity and skill that would free me from having to go back in any major way. Part of the affection I show him is meant to tell him that. Robyn get support in words and labour and attempts to rearrange the schedule to take some of the pressure off her; Dale gets that, too, but also gets a squeeze in a bar at 1 a.m.

Maybe that balance is a little unfair, but there it is, as hard to fake as it is to resist. And Robyn isn't at Chaps at 1 a.m.

In that same letter to Jane I said I'd been to a funeral. It was for Don Bell -- that shy, sexy young man I'd met at Hugh Brewster's party in 1972.

I'd seen him often since if, after the first year or so, no longer in bed. His disc jockey career had made him a community fixture: when not at a turntable he'd been sometimes behind a bar, at Malloney's, or Boots, which he came to manage.

He'd been in hospital for some time. Gerald had gone to visit. I hadn't. He'd said he didn't want to see people, or be seen as he was then, a colostomy bag hanging from his frail body, once so lush and full. I took that as my excuse, if one not really good enough. On May 22 he had died, 34 years old.

|

Moses of the Archives

James Fraser:

|

His funeral was not the first I'd seen, but the first for a friend dead of AIDS. Gerald and I went, going through the motions of a Presbyterian service "standing, sitting, hauling out hymnals," I told Jane, "without pretending to sing or pray."

I saw, as I would see again, how death could bring together the disparate parts of a person's life -- parents, family, friends; many strangers to each other -- with that person no longer there to move among them.

But tensions I'd sometimes see later were not in evidence: Don's mother knew many of the carefully dressed clones there, his life long familiar to her. Early on he'd bought her a subscription to The Body Politic and she had never let it lapse.

Another good friend had died earlier, but far away in Vancouver. James Fraser, the Moses of the Archives in 1976, had moved there in 1983 to get an advanced archival degree. Ken Popert, out for a visit, found James in hospital, weak, barely able to talk.

"Do you want me to touch you?" Ken asked. James nodded; Ken rubbed his hair. "That was nice," James whispered. Ken cried. James died on March 11, not yet 40.

In TBP's June issue Alan Miller of the Archives and Robin Metcalfe, Halifax activist, writer for the paper and frequent visitor to Toronto, did joint obituaries. Robin wrote of James's energy, his big beard, his rapid fire talk and his "driving mission: to gather into his arms the loose fragments of our history, a loving gift to future lesbians and gay men."

"Such people," Robin ended, "never die." Certainly his work never did, nor the memory of him. The book collection of the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives has, for years now, been The James Fraser Library.

But I'd rather we still had James.

Go on to 1985: July through December

Go back to Contents / My Home Page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1985a.htm

December 1999 / Last revised: June 18, 2003

Rick Bébout © 1999-2003 / rick@rbebout.com