|

Promiscuous Affections A Life in The Bar, 1969-2000

1992-1995

|

|

Media empire

Pink Triangle Press's

|

Few people working at the Press could recall the days of The Body Politic. What did the place mean to them now? Just a job? Or were they inspired, as we had been, by some deeper vision?

1994

April through December

In late April I was off to Vancouver myself. It was for work, my work now with Pink Triangle Press, creature of and heir to The Body Politic.

Near the end of 1993 Ken Popert had asked me to lunch. He wanted to recruit me, free then of ACT, back to the Press. My insurance company had no problem with me working part time: they got to deduct half of anything I earned from my disability benefits. I could do it for two years. If I could still work after that I'd be deemed no longer disabled and cut off.

I'd had nothing to do with the Press since I left its board in 1990. It was now an entirely different scene: more than 30 staff in three cities, the quandary of running a "national" medium from Toronto answered by starting local papers elsewhere. Xtra West in Vancouver and Ottawa's Capital Xtra were launched in 1993, nearly identical kin to Xtra, born of The Body Politic nine years before in Toronto.

The annual budget was now well over a million dollars, flush with cash from its classified ad and chat phone lines, developed by Colin Brownlee in 1990 and booming ever since.

Few of those 30 staff could recall the Press even in 1990, let alone the days of The Body Politic. Ken wanted me there in part to teach history. He also needed some ideas on the role of the board, and on policy: all those staff with no personnel code to guide them. These things I knew how to do, so I'd said yes to Ken and was hired as a consultant.

I began by interviewing everybody, board members and staff. There were no volunteers any more in Toronto, the last ones hired on two years before and no more recruited, though the pioneering operations in Vancouver and Ottawa had a few. I wanted to know what the place meant to these people. Was it just a job? Or were they inspired, as we had so long been, by some deeper social vision?

I found they were, but few passionately. The daily grind did not foster grand visions. The few staff meetings I attended dealt with little of substance beyond who would take out the garbage or feed the office cat (Kitty Lang, listed in Xtra's masthead). Soon the staff as a whole stopped meeting altogether.

Ken could recall a vision but found it hard to share. As of April 1, 1994 he had turned over his role as editor and publisher of Xtra to David Walberg, its art director, ascending to the presidency and executive directorship of the entire Press. Always a bit aloof, Ken was now remote even geographically.

Toronto staff were in three sites around Church and Wellesley, having "come home" only in 1990, to 100 Wellesley East. Now that space handled only display ads, classifieds, and the phone services (that is, the public). Production had moved to two floors at 467 Church, above Woody's; editorial, administration, and Ken were further north, obscure tenants of a concrete tower looming over Charles Street East. In October they'd be together again, on the second floor of 491 Church, Ken hidden away at the back in the new "national office."

I liked these people, kids most of them still, had hopes for them but was rarely inspired. As mostly they weren't. Nonetheless, I plugged on. But I knew the Press would not be, as The Body Politic had been, then ACT, the consuming passion of my life. Just as well, I suppose.

I had fun with the kids in Vancouver, fired up with more energy than in tired old Toronto, but also frustrated. Publisher Fred Lee had to get national office approval for even minor expenses. It wasn't yet clear what the relationship between that office and the three local papers should be. Ken's linear mind was inclined to control, but something in his gut said it might not work.

My most lasting contribution to the Press would be coaxing him clearly in the direction of local autonomy, letting the papers marshall their own resources -- with hefty infusions of start up capital from the Press's rich pot, but only for a year or two -- to meet their own communities' needs as they best saw fit. The gang in Vancouver, of course, thought that just peachy.

On April 23 I sailed off to Galiano, leaving the Press behind. It was a quiet visit, just four days, but with one moment of drama.

Jane and Helen had many Island friends, two of them Marek, a playwright, and his lover Allan, who did odd jobs, many for Helen and Jane, especially in their garden. We all went one night for dinner at the Pink Geranium, a wonderful restaurant on the north end of Galiano with lots of rich, tasty fare.

Too rich for Allan, his diet mostly vegetarian. Back at the house he was in pain, soon so severe that we called the ambulance to get him off island to hospital. It was a gall bladder attack; Allan soon recovered. But it was a frightening moment, particularly for Jane. There was that ambulance again, backed across the grass to the door, just as it had been for her father a few months before. I saw a look of strain and fear on her face that I had never seen before.

Apart from that we had happy times. An odd one came in a supermarket near the ferry docks on the mainland. Jane asked a cute young clerk where she might find palm hearts. He gave her a look, utterly uncomprehending: "Pop Tarts?"

|

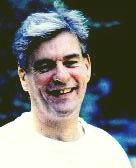

Here he is

Shel:

|

I was thrilled to see him if a bit daunted: he'd fallen out with Jack and had nowhere to stay. I offered my place again. He hesitated, knew I was busy now -- Terrell; reports for the Press; packing: Paul and I had found a house more quickly than we'd imagined -- said he'd try to arrange something else, but in the meantime.... It turned out a week, various bits of his impedimenta longer as other arrangements came up and fell apart. I wrote to Jane on May 19:

-

It was obvious it wouldn't work. I had too much else on my mind and could hardly get down to any of it when he was around. In the end he was the one to act. He decided to go stay at Covenant House [a Catholic run hostel; the kids called it "Cubby Hole"] despite its 9:30 curfew. A few days later he blew that curfew, stayed at the baths, made yet another arrangement he didn't want and then finally, this past Tuesday night, went to Turning Point, another hostel with somewhat more liberal hours.

I was a mess by then. He wasn't staying here but was here every day with some new brow creasing dilemma: no money for a transit pass (I lent it); no bike for work, having sold it on his journeys (I said what the hell I can put it on Visa, made it his birthday present); work hassles (he finally quit, then got another courier job). But I was using resources I didn't really have, not so much money as energy, presence of mind.

I told him on Tuesday night, "I'm not sure I can keep one life together right now, let alone two." He was great. "I have to get my own life together. You have to stop giving me things and stop worrying about me. And I need to give you some time for yourself." And he has: no calls for the last two days.

I'm not worried. He's a strong kid; there's no question about our affection for each other -- even if we don't know how to make it work at close quarters. And heaven knows I need some peace.

I had cried with him that night, as I had once before, once even with Ricky (who still called, but I rarely saw him). I did find the most understanding 20 year olds.

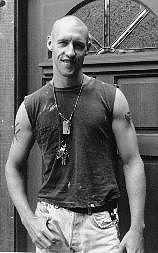

Shel had bought a disposable camera on his journeys, the film not yet finished. While he was staying with me we went out on the balcony and I used up the last of it, taking pictures of him. I sent them to Jane.

-

Here he is. The serious look is the one he liked best: I think it's how he'd like to see himself and he glowed when I got it blown up to sit on my desk. But the others are more him to me: tousled, grinning, clowning around.

He is, finally, older than he looks in most of these shots, his own man, insistent on that and learning gradually to take responsibility for it. He's worth a lot of love -- if right now more than I can give.

What I could give turned out enough. Shel and I would go on for some time, if with less intensity. I still have those pictures I took, colour prints on my wall just above my desk. So I can look up right now and see his grin.

And still, all these years on, I love that strong splendid boyman.

Later, just once more, I would.

Paul was having doubts, too -- about the kind of place he had told the agent he wanted. He began to see he was looking for the sort of house David would like. But David was gone, and Paul knew it.

The last place was in a new condo project on Summerhill Avenue. Beyond its fake Victorian exterior (if that) it was not David's style: clean and modern inside, three floors and a finished basement linked by an open stairway. The second floor held a big bedroom with its own bath, a mezzanine overlooking the living room, perfect for a desk -- the whole floor perfect for either of us. So was the third. I'd get the second, Paul later joking to guests that I'd taken the master suite.

The Summerhill subway station, just three stops south to Wellesley, was a short walk west; east were trails down to our old stomping ground, the ravine of David Balfour Park. We (that is, he) took it, had it painted in colours I selected and Paul liked, more dramatic than any he and David had lived with. Paul moved in on May 26, I on the 28th. On June 10, I wrote Jane.

-

Shel helped me move, the tousled hair under a cap but the ears and nose you noted [in the shots I sent] as appealing as ever. So was his trim little butt, cased in tight cycling pants, and his diligent Newf manner. He lugged, marshalled, said sotto voce about the hired movers, "These guys are lazy." He jibed to the guy in charge about one of them: "Where'd you get him, a temp agency?" He was right.

In the end he kept them moving in time to be done by five. He helped me get the bed in place, no sheets yet but he plunked down on it (his usual favourite spot) and got a massage I wouldn't have minded taking further, so lovely was he that day (as he has been since). But then, Paul's parents were just upstairs.

Shel would be back more than once, the sound of his bike skidding into the courtyard often my only notice. One June day he arrived hot, sweaty, his shirt soon stripped off, then his pants. His erotic appeal on the day of the move was fresh for me; it was always fresh, every time I saw him.

I caressed him, ran my face down his smooth stomach to his underwear, still on, through them took the firm ridge of his cock gently between my teeth. I looked up, to his face. "Shel, can I suck you?" We'd not had sex for a long time; I couldn't presume. He smiled. "Well, that's what I thought you were going to do."

I did, slipping a hand past his balls, probing his trim butt's ease -- not sure he'd like it but he did. I slid a lubed finger slowly into him, stroking his silky pulsing innards. He took himself, pumped hard, shot off wildly. He settled back, quiet. Then he smiled, almost pensive: "That was good." For me, too. It was the most intense sexual connection we'd ever had. He stayed for dinner, matching every one of Paul's flirtatious barbs.

That was the last time we had sex. If far from the last of Shel. In September I'd send Jane a scene from his latest visit.

-

He was over on Sunday for a while, wanted to settle for a bit, talk, then scoot off on his bike. We scooted together, down the paths to the park where we found Paul. An odd chat, Shel encased in his bike gear, a kerchief under his helmet pressing his hair down, his ears sticking out even more visibly than usual, his eye crinkling grin as engaging as ever, snappy wit, the necessary routine with Paul.

Paul and I headed back up to Shaftesbury Avenue; Shel streaked off south, skidded noisily into a U turn and zipped north up the path, his legs pumping, his butt in the air, all flying energetic young flesh. Free.

I loved him wonderfully in that moment. That's all I need.

Paul had a dinner party the day I moved in: his parents, David's mother, sister Janet, and her husband Diran. And me. It went well, but I was preoccupied. I'd been at Terrell's the day before. He'd been unconscious, on an even higher dose of morphine. The night before he had asked the nurse for an Atavan. "You might not wake up," she told him. He said: "That's alright."

I had called that night: he was awake, agitated. I'd been out of touch since, my phone not reconnected. I used Paul's to call the next afternoon: no answer. I tried again: the tape. I tried Ruthann: no answer there either. I finally got Mark, on a break from that dinner party, at 9:45 pm. Terrell had died at dawn.

In his agitation the night before, he had been able to say to Mark: "I love you." Mark held him as he long had not, even a hug too painful for Terrell. Mark slept soundly until the nurse woke him: Terrell's breathing had changed. He took a few more breaths, seemed to hiccup, then stopped.

As deaths go, Mark said, "I couldn't have wished for anything better." I said to Jane: "I suppose I couldn't have, either, Terrell marking my own transition, dying the very day I moved instead of making me carry him with me into this house, just as Paul moved here finally without David."

|

Life's effects

Terrell Cress:

David's tiles:

|

-

We had no conventions for someone gay, dying of AIDS, the family often foreign to the life just lost. Some new traditions have arisen, not all of them comfortable for everyone. Terrell more than once rolled his eyes, covertly, at yet another embarrassing moment in yet another "celebration of life."

But Terrell also knew that this wasn't just for him. It's for Mark, for his care team, for co- workers and family and friends who knew many different parts of his life.

People were invited to add their own embarrassing bits. "If you imagine Terrell rolling his eyes," I said, "count it as his last indulgence of his friends." And so they did. Then we had the party Terrell wanted. I had found one moment of the formal ceremony particularly apt -- its final song, k d lang's lament, flowing and languid: "I'm Down To My Last Cigarette."

Mark came up for dinner a few weeks later, Paul still not easy with anyone's grief but his own. Still, we all did well enough. I said there to both of them: "I'm glad I went through it all but, I'll tell you, I hope I never have to do it again. Especially two at a time."

Mark would find a house in the east end, small but big enough for a roommate, maybe something more in time. (Last I saw him, at another funeral, he had moved out of town.) Paul had taken his time answering letters of condolence, liking best the least maudlin.

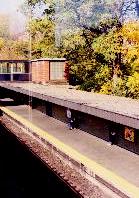

Two had come with city council citations, from Toronto and East York, honouring David's work making the transit system safer for the visually impaired. In 1992, for the same work, he'd been awarded a Canada 125 medal (as had Jane Rule that year, too). Months later I'd stand in the Summerhill station, watching workmen install bright yellow textured tiles along the edge of the platform.

David's tiles, I called them to myself, as I have ever since. Like Michael Lynch's AIDS Memorial. Even in death we have our effects.

Paul bought a big forest green Ford Explorer 4x4, a very Rosedale sort of truck, hardly his usual: the old Taurus; David's creaky Volkswagen years before. At times he'd be embarrassed about it, but then he'd say: "Oh well. I am trying to be someone new." As I suppose, in a way, we all were.

Gay people were pioneers of unconventional arrangements rich in support, commitment, love. Why not hold that up as a model?

Instead, we plead for the supposed security of a "spouse."

Spousal benefits -- & burdens

Future episodes in the relentless spouse fest -- touted as great "gay rights victories" -- would in fact burden people on social assistance, gay & straight, with new, involuntary support obligations. Even for some well off couples, as The Globe & Mail would put it, homosexuality became "the love that dare not declare its assets."

For developments to late 1999, see

For further silliness in the Name of Equality -- now very much wrapped in "that oddly respectable rallying cry" -- see:

History: As history

Gay Marriage? Wrong question

The push would now be to win for gay couples the same rights as heterosexuals in common law partnerships. It was called "same sex spousal rights" -- not a call for "gay marriage," as we'd soon endlessly hear in the US, but much of a piece with that oddly respectable rallying cry.

I found "spousal rights" a dreadful idea. A classic old saw seemed apt: Be careful what you ask for -- you might get it. In early 1993, the spousal spectacle already brewing, I'd had a piece in Xtra asking where the gay movement was going.

-

To Marriage and Family as the highest achievement of our "rights"? To an institution historically meant to regulate sex as a way of protecting property? To a model that long cast women and children as property? Some model.

Of course we're fighting for "equality." And so we should. But does equality mean sameness? Advances in spousal rights have not [as an earlier writer had claimed] "broadened the possibilities of how we live." On the contrary: of the richly varied relationships we create as gay people, only a few state sanctioned versions will benefit. Less conventional queers get left out in the cold.

State definition of relationships means their state regulation, turning some rights into involuntary burdens: divorce settlements; alimony; welfare benefits and tax credits cut for those supposedly sharing a common income. Governments, if otherwise skeptical, were quite tempted by the prospect of dumping social support costs onto a whole new breed of "spouses."

In May 1999 the Supreme Court of Canada would rule that "spouse" could indeed mean a person of the same sex. The issue in that case: alimony. Gay rights flacks of the day, blinkered by facile notions of "equality," would call it a major victory. "You want equality?" I'd written. "Try this":

- No one should have "spousal" rights. No one, by simple virtue of their personal relationships, should automatically have legal advantages other people don't. If any two people (or more than two, why not?) want to commit themselves to sharing what they have, to taking care of each other, they don't need a marriage. They need a contract: a legally binding agreement by which they -- not the state -- set the definition, rights and obligations of their relationship.

What's so special about conjugal coupling? Or living under the same roof? Queer people were pioneers of unconventional arrangements, domestic and otherwise, rich in love, support, commitment. It would be more progressive, more truly radical, to hold that up as a model than to plead for the supposed security of a "spouse."

I wasn't alone in that critique, shared by queer theorists, rights advocates with a more broadly human view of rights, and many friends whose political sense I have long respected. But radical visions would be blithely run over in the rush to one more respectable "right."

In early 1994 the NDP introduced a bill that would amend rafts of legislation to change the definition of spouse from "man and woman" to "any two persons." The Liberal leader had flip flopped on the issue; the NDP suspended party discipline, leaving its members to "vote their conscience."

In June 1994 the bill was defeated. Gay protesters packed the legislature screaming "Shame! Shame! Shame!" The Globe and Mail reported that chant as "Same! Same! Same!" -- a mistake, if one rich in irony.

Across the street, a crowd was dancing to a sound truck. We went over. A chord boomed out: "Gloria!" We all danced, waved our arms at all the right bits.

- Tuesday, July 5, 1994, to Jane:

I was out in it with Kevin Orr, visiting from London, his friend Bob Read, and Paul. It was Paul's first Pride Day since 1989, when he last took David out into it and found the crowds too daunting for sighted guide. We joined the parade and headed to Queen's Park. People shrieked whistles and waved as we passed police headquarters, a line of cops on a balcony far up. They waved back.

I found Shel. Or, rather, Paul found him, dancing shirtless and fiddling knobs, doing the music on a truck that, thankfully, was stopped. I ran around to where he'd see me but had to yell to get his attention. He grinned, jumped off and -- damn me -- I did not give him a big hug and wish him Happy Pride Day before he shot back up. (He called the next morning and I said that's what I wished I'd done. "Well," he said, "that's why I jumped off the truck.") I guess I was too stunned, too happy, too proud of him -- and I'm always a little hesitant when I feel I'm interrupting his work. He's terribly diligent.

Later we sat on the patio at The Mango for a few beers -- and many sights. Paul had been reminiscing about his first Pride Day, in 1972, and I said: imagine if you could have got even a fraction of the people just here at this corner out for that event. Mark Leduc, the Olympic boxer, was there in nothing but blue spandex shorts and sunglasses. I showed him to everyone. And everyone noticed this year's fashion statement: kilts, little ones, on men. Even some on women. And there were thousands of women, more than ever before, many young, some shirtless.

We went for dinner at Byzantium, got a table in the window, Church Street outside still filled with people. We waved and waved, so many we knew going by, coming in. Kevin got the waiter to stick a sparkler in Paul's dessert tiramisu for his birthday, a potentially depressing one, he'd said. We all sang, other people in the restaurant sang. Even people outside the window sang.

The music inside had been heavy on Motown, classic disco, the music of our youth. We joked that they'd have to play "Gloria," the last great anthem from the summer of 1982 -- in effect the last summer before AIDS. But they didn't. As we were leaving we saw people dancing to a sound truck in the big laneway across the street. We went over. Just as we got there an opening chord boomed out.

Bob yelled, "It's 'Gloria!' " We all danced, all waved our arms at all the right bits. I hadn't danced for years. Neither had Paul. He told me later: "This is the first truly happy day I've had since David was diagnosed."

Shel's diligence was most apparent to me in his new job, doing tech stuff at Colby's and Remington's. In time he would qualify for their benefit plan, George Pratt more generous with his employees than his dancers. It included dental coverage; Shel would come up one day to show me his new teeth.

He had a pager now. I'd call sometimes but usually felt I was interrupting him as he itched to get back to work. In late July I went to Remington's, distracted from the occasional tempting dancer by Shel's bouncy presence. But a serious presence, too, as I told Jane.

-

It's a perfect job for him: it fits his nervous energy, his intensity, his diligence -- and again he gets to wear a radio, this one with a headpiece. I do hope it doesn't go to his head: I suspect his standards could make him a bit of a tyrant. One of his jobs is to make sure the boys aren't getting blowjobs in the backrooms.

But he said, "I don't care about that!" He's more likely to stand guard than intervene, having once got a blowjob himself from a dancer (one of the truly gay ones) trying to work himself up for the stage.

He's still such a joy. He asked me as I was leaving last night, "Aren't you going to get a dance?" And I said "No, why? I've got you. You're fabulous." He smiled and bopped off on a radio call.

In September Shel would tell me George's Townhouse had closed, in debt, its door padlocked by the sheriff. Ah well, no more sweet indigent boys. With no boys dancing at Colby's now, I never went.

"Master Nemesis"

|

I bumped his arm, apologized. He popped back, grinning: "That's OK! You'd have to hit me a lot harder than that to hurt me!"

-

A man I'd seen for years asked me to dance and then dragged me out to the back deck to play -- that certainly hasn't happened in ages! Last night, being the Sunday night of a holiday Monday, had more tourists and dilettantes. You can always tell: they don't know when they're standing in traffic or in the way of a pool shot; they're often in chatty pairs, a more experienced one showing a novice around; they dip into the backroom, giggle and scoot out.

One of the faults of tourism is that it spares you any investment in the place you're touring: it's not yours; you don't have to respect the local customs or consider the inhabitants; you can use it for your amusement, understand none of it, need none of it, really -- and go home. I don't like weekend nights there much, but for sociology lessons.

The Barn had been famed for chance quickies, its dark nooks so convenient. Now serendipity was falling to contrivance -- as in so much of gay life. The place would soon get cheap plywood private booths, and a "maze" -- a room sized wooden box with a few narrow dividers. I came to call it "the crate."

For now The Barn's "backroom" was just a small space off the third floor landing -- with all its lights turned off. A fire escape led from it to the second floor deck, a few oil drums piled up there offering some cover -- if hardly complete privacy: scenes could sometimes draw a small if appreciative audience.

I once did a nice young man behind those barrels. It began as a mutual crotch squeeze; I got his cock out first and went down on him. After he came I stood up; he smiled and told me his name. Coming out past a few gawkers, someone said: "That looked like fun." I smiled: "It certainly was."

In its less self conscious ways The Barn could offer, as it had for so long, some odd and wondrous moments. One night I was captivated an electric little creature on the dance floor: camouflage pants, black boots with high polish, a Canadian Army dress shirt and a red beret -- all on someone about five foot three, likely way too short to enlist.

His dance style was jerky, mechanical, gestures I knew from Shel at my place bopping to his headset. We didn't talk but for a brief exchange at the bar. Ordering a beer I accidentally bumped his elbow, and apologized. He popped back bright faced: "That's OK! You'd have to hit me a lot harder than that to hurt me!" I later saw him salute someone and, while not smoking himself, reach eagerly to light other people's cigarettes.

What a queer little vision he was, queer even for The Barn. But I suspected we might not hit it off. I found him later in a magazine, shots taken at Boot's "Fetish Night." The caption read: "Master Nemesis." It needed a hyphen: Nemesis of Masters, I'm sure.

At 95 Summerhill, Paul and I were getting on well. If not without a few bumps. Over his 22 years with David, Paul had grown fond of domestic sparring. Their spats rarely went beyond comic opera, each scene saying: I'm still here -- and so are you. I, so used to solitude, didn't rise well to Paul's occasional pokes. In time he saw that, saying, "I can't treat you like David."

With David gone, Paul faced what he'd long not had to know: romantic insecurity. He was gaga about a man at the YMCA, going on about him endlessly -- but had not yet dared say a word to him. "A hello," I once told him, "isn't necessarily an invitation to show up at the door with all his furniture." "I know," he said -- "but I wish he would!"

He used to joke that I got into sick relationships. "Now," he said with some glee, "I've got a sick relationship, too!" In time he did talk with that man. They took to going out for coffee; he came to visit. It didn't become an affair; such passions often don't. Years later, they remain friends. I wrote then to Jane:

-

So much of what Paul is having to learn only now I feel I've known for as long as he's known me: that there is only the thing itself; that it matters for itself; that you can't go home to someone who lets you believe: I have my relationship -- thank god -- and everything else is irrelevant.

It is a great loss (of citizenship, among other things) to believe you don't need the world as anything more than a diversion. But then you've heard more than you need about how hard all this grand theory has been for me in practice. Still, you can see why I hate bar tourists and spousal rights -- and love my random boys.

Paul was an exemplary citizen, an old gay liberationist, his work about human rights, pay equity, justice on the job -- and in the world. But in certain vital ways he had not, for years, really needed the wider world. Now he did.

He was also resolving his private grief well enough to allow the grief of others, even grief less private, more communal. He would soon have to allow me a good deal of it.

- "There are such men in this city, and even to see them, never mind to touch them or have them kiss you, or see them just before dawn, or to have them as one of your dear friends, is one of the greatest pleasures of our life, and it is commoner than most people think."

Neil Bartlett

in Ready to Catch Him Should He Fall, 1990

In September, someone who knew Kevin Hunt -- that lovely man from the fundraising office at ACT who had skipped off to London in 1989 -- told me Kevin had died there. He didn't know much more.

I knew almost nothing. I had never tried to look Kevin up on my visits to England. He'd been back for a visit once here; I'd had dinner with him and his Swiss lover of two years, a rather severe man. But his presence had been useful: it checked any rekindling of my easy passion for big, strong, handsome Kevin Hunt. But I had been very happy for the chance to see him again. Now, he was gone.

Then someone told me about Vince. I have told you about him, if just a bit: that rather severe young man who smiled a boy right out of The Toolbox in 1988. I'd seen him often after that, at Showbiz, at The Barn, watched him dance, so lovely that I wished for a way to live in his crotch as he sailed across the floor.

I didn't know his last name. I called him -- to myself; we'd never spoken -- Vision Vincent. Later I'd see him at ACT, a volunteer doing holistic heath work, Vince Albone now, if still a vision and rather knowing it (well, I'd think, why shouldn't he know it?). I got to watch him dance again at an ACT Christmas party.

I told him there how beautifully he moved, confessed that I had watched him dance for years. He smiled, left me, went back to the floor and of course I watched. He came back, sat down beside me and asked: "Did you enjoy that?" I had, very much. And then I found out he was dead.

When Pink Triangle Press moved to 491 Church Street in late October 1994, we had a staff party there. Kevin Bryson's name came up; how, exactly, I cannot recall. All I remember is someone saying: "You know he died last Tuesday."

David Walberg, sitting beside me, said: "Maybe you could write his obituary." "No, I don't think so," I said. "I didn't really know him well enough."

|

Particular magic

Kevin Bryson

At the University of Toronto, early '80s; later at a Pride fest on Church St. Photos courtesy of John Flack.

John first met Kevin at the U of T, taking many shots of a young man who (as that nose suggests) had grown up no "cute kid" On his application Kevin had written: "I'm gay." John got to watch Kevin, his best friend for the rest their lives together, make himself a gay icon. Consciously -- if never as iconic to himself as he was to so many of us.

For more pictures of Kevin, one brazenly iconic, see the bottom of this page.

|

A vision seen in bars, on dance floors; a man whose mere presence makes you glad to be alive. That's the warp & weave of gay life, these casual, deeply pleasing connections.

Then you hear he died last Tuesday.

I gave myself a lot of time to cry that night. I didn't know him well enough, I'd said. Maybe that didn't matter. What little I'd known of him I had in fact known, and loved. Maybe I could just say that. At 11:30 pm I sat down to my computer, got very drunk and pecked away until 2:00 in the morning.

-

This is about a man for whom I once bought a pair of shoes.

His name was Kevin Bryson. This should be his obituary, but it's not. I don't know all the things you're supposed to know to write an obituary: date of birth, noted accomplishments, date of death, survived by -- all that. I heard only tonight, a Friday night in late October, that he died last Tuesday. Three days ago. Or ten. I'm not sure.

I do hope someone who knew Kevin truly well will say all the things that should be said about him. I just want to tell you what I know. And about the shoes.

They were red shoes. They were very small, baby shoes with round toes and a strap across the instep. I put them into an adult sized shoe box stuffed with tissue paper and left them outside his door. He lived at Church and Wellesley then, right over Ernie's barber shop. That was December 1985.

It was an inside joke, a flirtation without intent. We'd been at Cornelius one night and caught on TV a bit of The Red Shoes, a 1948 movie in which, as I recall, ballerina Moira Shearer dances herself to death. More often at Cornelius I watched Kevin himself dance, his hips his centre of gravity but somehow magically light, carrying him with immense grace and beauty and sweat across the floor.

I've watched many men dance for many years, before and since. But no one has ever been as beautiful as Kevin.

We did know each other beyond that, just a bit. I'd see him at The Barn or out on the street, sometimes with his boyfriend Ted, sometimes alone, the last time only a few weeks ago. You may have seen him. If you go to Sailor he's the man on their poster, in nothing but a navy cap, clutching his crotch.

Maybe that's all you need to know. I never knew much more. Only that he was graceful, smart, reserved. I knew him as you may know someone you watch dance, maybe chat with from time to time, and then -- who knows?

Too many deaths I've known only like this: a vision seen in bars and on dance floors; a few friends in common; easy nods and smiles on the street -- someone whose mere presence makes you, in some small way, simply feel good to be alive. That's the warp and weave of gay life, these casual, deeply pleasing connections.

And then you hear he died last Tuesday.

You'd think we'd be used to it. I thought I was. But tonight I have cried as I never cried, not right away at least, for friends I did watch die. I suppose I'm crying for them now, too. And for other, seemingly casual visions. For one named Vincent; you may have seen him. For another Kevin, Kevin Hunt -- more than casual but not an affair either: just (just!) the affection gay friends can know so well.

And for Kevin Bryson, for his magic and beauty -- a huge gift to the world, honoured once by me with a small and silly one -- gone now, except in memory.

I know I'll see magic and beauty again. It's all around: you only have to look -- to pay true, generous attention -- and you'll find it.

But not Kevin's, not his particular magic. Not ever again.

The piece appeared in Xtra a week later (in somewhat different form; I've edited it here) and with a subtitle: "A reflection on one loss too many." It would have more impact than anything I'd ever written there.

Many people told me they had read it, calling me, stopping me on the street; one rushed out of Bar 501 to catch me and say so. Some shared their own memories of Kevin. But most said: That's how I've felt for so many people, but I never knew how to say it. They wondered, it seemed to me, if they even had a right to grieve for someone they had barely known. But we do.

Three years later I'd be asked if I could read that piece for a three part Ideas series on CBC Radio, called "Sex, Death & Grief." I agreed, did a shorter version, and called producer Ann Silversides about it.

"Don't cut the shoes!" she said. I had; I put them back in.

|

There would be more deaths, if for me none too close. Nor any touching me the way Kevin Bryson's did, with feelings for those not "close" as we too easily define it -- but there, in the world, & wondrous.

He said he wasn't sure he knew who I was. I knew he was Ted behind the cooler bar at Woody's; Ted who'd been in those white Calvin Klein boxer briefs on that Pride Day float in 1992. I called him back.

Ted invited me out for dinner, at PJ Mellon's on Church Street. He showed me pictures of Kevin, some porn shots, some home snaps. He told me of Kevin's time in hospital, some immigrant housekeeping staff wary of him: he looked like a skinhead, maybe a Nazi. He was a skinhead. So was Ted -- both members of SHARP: Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice. Kevin had also got Ted involved in anti censorship work.

"And the baby shoes!" Ted exclaimed. "How did you know Kevin and I were fascinated by babies?" Of course I hadn't. But for him it said that, even in 1985, I'd got something right about Kevin.

At the end of our dinner Ted raised his beer for a toast. "To Kevin," he said. But he wasn't lost in private grief. "And to Vincent" -- whom I don't think he knew -- "and to Kevin Hunt," whom he did. He gave me a memento of Kevin Bryson: a little plastic pig standing up on firm bristles. His fingernail brush.

An odd gift, I suppose, if no more silly than baby shoes. I still have it.

George Smith, once guiding light of the Right to Privacy Committee, housemate to Tim McCaskell and Richard Fung, died in November. So did David Chang, Danny Cockerline's boyfriend in 1982, who used to sing while he worked the night away with me at The Body Politic. He'd gone to theology school in the States, becoming a deacon.

There were two young men I'd known working the front desk at the Press; later another there, Perry Barone. I had first seen him working the upstairs bar at The Barn, a fierce cropheaded boy wearing nothing but his underwear. At the Press, even as he grew unwell, Perry wanted to keep working. He would come talk to me, seeking advice. I said: as long as it's what you want to do, do it. He did, until he could not. Ken Popert and I sat together at his funeral.

There would be more deaths, if for me none so close, so daily, as the deaths of Terrell Cress, David Newcome, Michael Lynch, Michael Wade, and Bill Lewis. Nor any touching me in quite the way Kevin Bryson's did, and eight years later still does -- showing me how much one might feel for those not "close" as we too easily define it -- but there, in the world, and wondrous.

Well, not for some years. In October 2002 Robert Trow, living with HIV longer than I have, would die not of AIDS but a brain aneurysm. He'd said to me just the week before: People seem to think no one dies anymore. He had worked from 1976 at Hassle Free Clinic, seeing hundreds of people, like us, living with HIV.

At a memorial service unanticipated even a week before, Gerald Hannon -- the love of Robert's life and he of his, long after they were seen as "lovers" -- spoke "of the worlds that Robert was, and of the worlds that he helped to create, and of the worlds that helped to create him." Worlds of our own creation. Creating us.

|

Whataguy!

Shel wrapped for Christmas.

|

I bound their 18 pages in a plastic cover, put them in a burgundy coloured folder, and wrapped it in wonderful gift paper I'd found by chance, its design in silver and blue a repeating pattern of the same conflated phrase -- "Whataguy!"

Shel opened that gift on my bed, sat reading. He grinned, after a bit put it away -- then picked it up again, read for another half hour. After another easy, affectionate hour he scooted off.

- December 31, 1994, to Jane:

I asked if any of it embarrassed him. "A bit," he said. He's called twice since, our relationship -- even if now dangerously articulated by me in a way he would never say himself or even comfortably hear -- the same as it's been for a very long time: simply happy making.

Enough for tonight. In 15 minutes it's 1995. This is a very nice way to bring in a new year.

Go on to 1995: Jan-Sept / Go back to Contents

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1994b.htm

January 2000 / Last revised: November 21, 2002

Rick Bébout © 2002 / rick@rbebout.com