Giving it away

The Body Politic:

Life in a culture of gifts

-

"We were doing exactly what we'd hope to be doing

if we didn't have to work for a living."Chris Bearchell, on being with The Body Politic

|

Giving it away

The Body Politic:

|

|

|

|

|

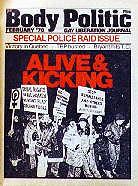

Weekend's crew (& The Body Politic's)

Left to right; back row:

Seated:

On the floor:

|

On December 17, 1977 Weekend Magazine, a Saturday newspaper supplement, ran a two-page picture of 15 men, six women, and a baby. The caption told us their names and roles, among them: businessman, curator, authors, professors of sociology, microbiology and English; librarian, university student, engineers electrical and chemical; office worker, photolab technician, typesetter; two civil servants, one a graphic designer -- and a teacher also a mother (with baby).

The spread was titled "Gay in the Seventies." It led off a feature by Ian Young, among that photo's authors, on "the substantial but precarious progress gays have made in Canada." Ian noted that curator, Charlie Hill: in 1969 both had been among the founders of Canada's first gay liberation group, UTHA, the University of Toronto Homophile Association. Four others in the picture were mentioned as "recent come-outs." There was no suggestion that these people otherwise shared any connection. Apart from being "gay." Canada's leading gay journal The Body Politic featured that shot in its next issue (February 1978, shown above), leading its media-analysis column "Monitor." It reported that Weekend had wanted:

What Weekend had actually got (perhaps inevitably given the times: a poll in the same issue was headlined: "Most Canadians think homosexuals are 'sick people'") was a gaggle of gay activists. The Body Politic listed their unmentioned connections: with the Community Homophile Association of Toronto ("businessman" Ron Shearer, not his lover George Hislop, CHAT's best-known "professional homosexual"); with GATE, the Gay Alliance Toward Equality; with Gay Youth Toronto, Gays of Ottawa, the National Gay Rights Coalition and the Gay Academic Union; the Gay Offensive Collective (doing TV); with LOOT and with LOON, the Lesbian Organization(s) of, respectively, Toronto and Ottawa (Now) -- and, that lesbian mom, with the Revolutionary Workers' League. They also had another connection. Everyone in that picture (even the baby) had appeared, or later would, in the pages of The Body Politic: nine as writers of or players in stories; seven as regular contributors; five -- Ed Jackson, David Gibson, Michael Lynch, Bill Lewis, and Chris Bearchell -- as former, current or future members of its editorial collective. The Body Politic, the first of its 135 issues dated November 1971, the last February 1987, has entered history as "Canada's national gay liberation journal" (in Tom Warner's 2002 Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada), "a crummy, dirty publication without a redeeming feature" (the Toronto Sun, 1977), and "one of the most intellectually and politically sophisticated papers of the era." That last is from Rodger Streitmatter, in his 1995 Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America. The only non-US paper he gives even a mention is The Body Politic. At its height, a third of of its readers were outside Canada, one quarter "in America." It has also been called radical. The Body Politic insisted not just on "gay rights" but gay liberation -- as a route to wider human liberation. Its politics were, as has since been said, "consistently community-based, sex-positive, anti-censorship, and supportive of choice and self-determination." This was, literally, the politics of bodies -- not just "gay" bodies but everybody, socially connected in that more ancient meaning of the phrase "the body politic." The paper is likely best known for having fought, as Streitmatter put it, "the most strenuous censorship battle in the history of the gay press," raided by police in December 1977 after running a piece called "Men Loving Boys Loving Men," again in May 1982 for one on fist-fucking. The cases dragged through the courts for nearly six years, acquittals twice appealed by the Crown, ordering new trials. The paper's legal bills topped $100,000 -- covered almost entirely by community donations. And, in the end, we won. The Body Politic has also been seen as "the house organ of the Canadian gay movement." It was not: the movement was too varied to have one official voice. Even the paper itself, very much part of that movement, spoke with many voices, often similar if none the sole "authorized version" of Canadian gay-activist ideals. The Body Politic's role in reporting on (as well as engaging in) activism did make it, more or less, the movement's "newspaper of record," if never to the complete satisfaction of every avid activist across the country. It is as that newspaper of record that The Body Politic has most entered the historical record of our lives in its lifetime. Long after its demise it is still, as one researcher has said, "invaluable as a documentary source of Canadian gay history." It has sometimes been seen as little more than that: a source somehow (and thank god!) just there. Exactly how it got there, how it worked, or why it worked the way it did, can seem questions no more pondered than, say, why The Globe and Mail or the New York Times are "just there." We can find most of the people in that 1977 photo, and many more, in works on Canada's gay and lesbian history (rare as such works are outside the academy: a few books and films; occasional pieces in periodicals). We can usually find their formal affiliations: with this or that organization (often just one, though they tended to get around); those groups with each other in coalitions. But we cannot always find less formal connections: more intimate, organic, maybe even domestic. Or erotic. (There are exceptions, if rarer still: a few biographies, and one book tracing the rise and fall of LOOT: Becki Ross's The House that Jill Built: A Lesbian Nation in Formation.) Key players often appear one at a time -- individuals or organizations apparently autonomous, raising blips on history's radar when they said or did something of import to a particular moment in the story line. What happened before they rose into view -- their experiences; the connections that may have shaped their beliefs, their commitments, their actions -- often falls off the radar. These people too can seem, somehow, just there. What their lives were like beyond notable activist episodes often goes unsaid. Maybe, if unrecorded, that's simply unknown. Or, if known, it's seen as not worth noting, not part of the real action. Maybe they lived much like anyone else: just your "average gay people." Philosopher Roland Barthes once spoke of "tracking down, in the decorative display of what goes without saying, the ideological abuse which is hidden there." I don't suspect many historians of abuse, but some tend to portray past lives in terms comfortably familiar to their intended audience. What actually happened, how and why it happened -- assuming we even know -- can, often unconsciously, be shaped to fit the "common sense" of the day, so pervasive it's invisible, presumed as simple reality: "That's just the way things are." I've come to call it "retrospective normalization." Sometimes all it takes is a word. "Journalist" for instance, with its noble ring of "objectivity" -- a fraud The Body Politic never bought into. Or "publisher," "editor," "staff" -- all said to have "worked" in its "office." All conventional terms: most people know what they mean. But what the hell was a "collective"? Even writers who mention "The Body Politic collective" rarely try to explain it. |

Issue 1

|

For the 13 men and two women who came together to birth a gay paper in 1971, "collective" was not an odd concept. It was a model they knew, familiar among people hoping to create countercultural alternatives to the stifling order of "the establishment." They had come from women's liberation, leftist groups, and Toronto Gay Action, CHAT's radical spin-off. They had no professional credentials, no financial resources beyond pocket money, no market surveys, no business plan. They had nothing but each other -- and a passion to put ideas out into the world. They did not ask anyone's permission. They just did it. They wanted to share power as equals, rejecting formal hierarchy: they made decisions together, usually by consensus. They wanted to work for themselves, for other gay men and lesbians, and for the gay movement, not for a boss. Or an owner pocketing the profits of their collective labour. Not that there were any profits. Or, for a long time, even pay. By the mid-'70s a few people were paid, less a market-level salary than a living allowance: freed from the need to go make a living in a real-world job, they were expected to devote their lives to The Body Politic. In 1977 just two "staff" were paid, Gerald Hannon and I, at $8,000 a year. We sometimes worked up to 80 hours a week. But we were not the only workers. By 1982 -- the peak year for editorial content, each issue the work of more than 100 people -- there were just six paid "staff." For its entire history The Body Politic depended on people giving their work away. They wanted to, motivated not by pay but passionate engagement. In 1975 they got an "owner," The Body Politic setting up Pink Triangle Press to be the legal proprietor of an operation already more than three years old. The Press was incorporated not-for-profit, without capital shares. There was nothing anyone could personally own. Or sell. Some gay papers born much like The Body Politic did get sold: in 1974 The Advocate went for $1,000,000. Its sellers had bought the rights to it five years before -- for a buck. Collectivist ideals clearly shaped (if sometimes not so clearly) how people worked at The Body Politic -- none more so than resistance to rigid structures, formal authority and, behind both, a commitment to treat each other as equals. There were no titles marking rank, no chain of command. And no pay scale: the few paid staff always got equal pay. Early on, the collective resisted "specialist expertise." Founding member Herb Spiers recalls fellow founder Paul Macdonald, who'd been with Come Together, collectively run by London's Gay Liberation Front, telling him: "We're all going to do everything together -- write articles, do paste-up, go out and sell the paper." For a while, Herb said, it was anarchy, early issues "not even embarrassing, just totally amusing." In time people did gravitate to tasks they did best. Or best liked to do. But few ever did just one hermetically sealed "job": no one was solely an "editor," "designer," "ad rep," "bookkeeper," "receptionist," or "janitor." Anyone might (and paid staff often had to) do anything they knew how to do. They learned how mostly from each other. People were less valued for pre-existing skills than for how well they could develop and share them, for what they could contribute to the paper's own "body politic." Including its politics. Many people got their political education working on the paper. Those who arrived "pre-politicized" often found their perceptions refined as they all worked together, everyone steeped in the stew, the very lifeblood, of life at The Body Politic: endless talk. That's usually what it takes to find collective consensus. The collective were not, by themselves, The Body Politic. At first they did make almost every decision, even vetted every article. As that work got too big they gradually devolved decision-making power to smaller groups: paid staff (all of whom had to be members of the collective), and "working groups" growing up around particular areas of endeavour: news, reviews, features, administration. Some people in each group were on the collective, but most were not. Or not yet. Also working by consensus, these groups became mini-collectives, training grounds for the main one. And for efforts beyond. At its best The Body Politic was, as I'd later say, "an activist academy." Even, via its pages, an open university. It was also open as an organization, more porous that the average "workplace." No one had to apply for a "job" to get in: all they had to do was walk in and say they wanted to help. At first, if they helped they were in -- all the way: work on a single issue was all it took to make it onto the collective. But that centre of power soon got less porous, wanting more time to suss out each new arrival's personal politics. In time they'd consider inviting (and people had to be invited) only those who'd stayed around at least six months. Staying-power became a road to power. The paper worked on trust, mutual regard, friendship; such things take time to grow. Everyone may have been formally equal, but everyone knew that some animals were more equal than others: the ones who'd been around a long time. Or were most articulate. Or who had shown, or looked like they might, a passion to keep The Body Politic alive -- by giving it a big piece of their own lives.

|

Hotbed

Spawning ground

|

These people didn't always work in an "office." The Body Politic was born and grew up at home. In more than one house, some shared with founding member Jearld Moldenhauer and his Glad Day Bookshop. The paper didn't have a real office until the spring of 1974: a storefront shared with Toronto's Gay Alliance Toward Equality and TBP's new baby, sheltered by its parent in later offices too, growing up to become the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives. Even once it had an office, The Body Politic was fed from home. Many homes: the places it had shared with Jearld housed not just him but others involved with the paper over time. Many people key to the life of The Body Politic, to the gay movement, and to social movements beyond, lived in what were not just homes but hotbeds of talk, thought, and action. There were lots of group households, some more or less collectively run, none the nest of just one conjugal couple. Some 150 players (that I know of) in The Body Politic's history shared domestic digs beyond à deux. Ed Jackson, Gerald Hannon, Robert Trow, Tim McCaskell and Chris Bearchell all lived and worked collectively for their entire time at the paper, all there well more than a decade. None of their households had fixed populations, ever seeing new "roomies" -- many growing up to become comrades-in-arms. These activist households were how we raised our kids. These odd ways we worked and lived rarely make it into histories that treat The Body Politic as a little more than a "documentary source." The final product, not the living process, is all that seems to matter. We're left to assume it was a "business" much like any other: a "newspaper" "staffed" by "journalists" leading presumably normal lives: off in the morning with a kiss goodbye to the spousal unit (or the cat) for the usual Monday through Friday 9 to 5 "job," maybe finding some "spare time" for some "worthy cause." Or a "social life." I put these apparently normal terms in quotation marks to disown them. Our lives were not like that. Had they been, The Body Politic and the movement it was part of -- in fact any grassroots movement meant to change our lives -- likely could not have happened. Such efforts grow not just from individual convictions but webs of connection: relationships complex, intricate, ever in flux; some formally "professional," others (and more vitally) personal, intellectual, emotional, affectional. Or, as poet Audre Lorde once put it: erotic. She defined that word as "the open and fearless underlining of my capacity for joy"; she felt it "dancing, building a bookcase, writing a poem, examining an idea." I felt it at The Body Politic. And I was not alone.

|

|

It was not until 1985 that I discovered our odd ways of living and working could be named. And that, beyond the presumptions of Western capitalist culture, they were not so odd. The revelation came in a book, one recommended by pioneering lesbian author Jane Rule, who wrote regularly for our little paper. She told me it had made her see why, though making her living as a writer, she had for years given her work away to The Body Politic. (No one ever got paid for what they wrote.) It was The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property. Using, as one review put it, "anthropology, economics, psychology, art and fairy tales to examine the role gifts have played and continue to play in our emotional and spiritual life," author Lewis Hyde looked at cultures where status grows not from how much one owns, but how much one gives away. Not as charity, the "haves" being nice to the "have nots," but everyone giving to everyone -- without putting a price on what they give, or what they might get in return. Gifts move in circles: they come back to the giver as part of that circle. And they come back transformed, enriched as they were passed along. Gifts build meaningful human connections. They help sustain communities, creating what Hyde called "gift cultures." Margaret Atwood, who had passed The Gift along to Jane Rule, would later write:

Hyde called gifts "anarchist property," noting similarities between anarchist theory and gift cultures: "both assume that man is generous, or at least cooperative 'in nature'; both shun centralized power; both are best fitted to small groups and loose federations; both rely on contracts of the heart over codified contract." And both "share the assumption that it is not when a part of the self is inhibited and restrained, but when a part of the self is given away, that community appears." He traced his perceptions back to French anthropologist Marcel Mauss and his 1925 "Essai sur le don." His thoughts were resurrected in the late '60s by another MAUSS: le Mouvement Anti-Utilitariste dans les Science Sociales. Its thinkers find gift cultures not just in the past or among "primitive" tribes, but co-existing with our world's dominant culture of cash. Who, they noted, asked to donate a kidney to a sick sibling, would calculate its price and demand payment? People who have given a kidney say that never occurred to them. Not even whether they'd give it. They just did. Gift culture, "best fitted to small groups and loose federations," kinship groups the most studied model, got hard to maintain as The Body Politic got bigger, forced to survive in the world of cash culture. Despite shunning centralized power, trying to check even informal power, some animals had become not just more equal but, as we'd come to say, "dinosaurs" (all male) trampling young "mammals" (increasingly female: Chris Bearchell, long called The Body Politic's "only lesbian" if never a token one, had been recruiting). Men at the paper long thought themselves feminist allies; the women they worked with, 17 over time on the collective, sometimes had cause to doubt it. And who counted as "kin"? Just how far did The Body Politic's extended family extend? Even within its walls that wasn't entirely clear. By the mid-'80s many in its changing communities had come to see it as a tool of privileged gay white men, their sole aim "sexual libertarianism" and the end of censorship (especially of their own paper): cavalier about pornography, careless at the intersection of sex and race; even "racist." We were mostly not privileged, and not all men. But we were overwhelmingly white. And we had mostly stopped talking. We were too busy, by 1984 putting out 12 issues a year of The Body Politic (born a bimonthly), another 24 of Xtra, its small if sprouting offspring. The end came with questions of whether we should even go on trying to run the whole thing as a collective. We did not. By 1987 The Body Politic was dead. Xtra and Pink Triangle Press survived, if not as collectives. By the mid-1990s, anyone who did anything there (but sit on its board of directors, nothing like the collective) got paid to do it. That was rarely their sole motive, but their culture had become one based on cash, not gifts. It was the biggest if barely noticed sea change in the entire life of an endeavour born in the bright dawn of liberation. Gay liberation, Tom Warner says in Never Going Back, is not dead. It survives on the ground -- beneath the radar of practical "assimilationists" rushing for the right to be just like everybody else. Even as our truest gift has always been our difference -- our distinct ways of being, and of seeing life around us, often more perceptive, more creative, more generous and humane, than the world's usual. But the world has gone back. To glorified greed, to personal wealth and public penury unmatched since the Gilded Age of the 1890s (and all seen, yet again, as merely "natural"). To deluded dreams of Fifties-style "domestic security" -- in private, state-sanctified, safely cocooned coupledom. Few dream of the communal connections many of us knew as men and women "Gay in the Seventies." And beyond. Some can't even imagine them: they're no longer valued in the stories we tell about ourselves; no longer a vital part of who we think we are. But we can think again. As a writer asks in The Question of The Gift: Essays Across Disciplines:

In the May 1978 issue of The Body Politic, Gerald Hannon told a story of who, then, we were trying to be. In a photo essay on two men pondering how to live as a couple without sacrificing their public commitments, passionate friendships, promiscuous affections or sex in the park, Gerald asked: "What are we all doing?"

He told of Ezra Pound instructing his poems:

"If we can be disruptive social poets with our lives," Gerald wrote, "we can go to practical men who have married practical women to raise practical children for a practical world and we can say: 'Not only are we going to live forever. We are not going to live like you.'" |

|

|

|

|

|

Weekend Magazine photo: a Croydon-Reeves Production.

For further comments by Margaret Atwood on The Gift, see her review of Lewis Hyde's later book: Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth and Art.

Much more on the life and times of The Body Politic (and my own) is available elsewhere on my website. For the paper's early years see On the Origins of The Body Politic; some of its sustaining households appear in the chapter called Baby steps. The life I knew at the paper is detailed in Promiscuous Affections in chapters dated from 1977 to 1987. Three later chapters, two titled Media, the other Citizenship: In the world and at work, offer further thoughts. As does another piece on the site: Gay "journalism": What for? For extensive details on the dismal politics of those who came to see "private, state-sanctified, safely cocooned coupledom" as the highest goal of gay/lesbian activism -- & on their ultimate "victory" in Canada -- see Gay marriage? Wrong question.

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/gift/index.htm

|