QUEEN STREET

Parkdale

Roncesvalles

Spanish name, Polish downtown;

one avenue, many stories

|

"Ronsi"

If here at Queen, its south end (& Queen's west), Pawlowski's Boustead at its north. |

-

" 'Ronsi,' announces the driver, as the streetcar halts at the first stop on Roncesvalles, just past Boustead. Several people are waiting at the tram stop -- Poles, Serbians, Iranians."

-- Andrew Pawlowski: "Ronsi -- In other words a TTC romance,"

in The Saga of Roncesvalles, 1993

Accounts of immigrant experience, I have found (even in recounting my own), can have certain themes in common. Oppressions escaped; travails endured; triumphs achieved -- no surprise, any of it. If never the whole story.

Mark Starowicz, child of Polish immigrants, executive producer of the CBC's Canada: A People's History, has called all Canadians "children of the debris of history." Our "founding peoples," habitant, Loyalist, First, were all conquered people -- displaced, defeated, abandoned by imperial masters -- joined by people fleeing war, famine, poverty, or persecution. We are, as I've put it, "Losers -- who sometimes win." If some winning more than others.

What we win, when we do, is sometimes simply the chance of a better life, maybe one more just and humane; maybe the chance to pass on our chances to posterity. Modest triumphs, really -- unless, perhaps, seen in the light of the world's wider and less lucky history.

From all of that, we make our stories -- often careful, partial, partisan. In Canada sometimes officially partisan: more than one immigrant history I've found lining library shelves has been helped into being by Heritage Canada, often led off by a supportive letter from the local (usually Liberal) Member of Parliament. I suspect any source meant to stand as "the official story," the single authorized biography of an entire people. There is always more than one story.

A late acquiantance, art critic and curator Peter Day, raised in South Africa, was once asked why writers in his native land, then still in the grip of apartheid, had produced so much powerful literature. He said: "They have a subject."

|

"Hero of two worlds"

Thaddeus Kosciuszko, here in his heroic American role, painted by a Pole: Kosciuszko at West Point by Boleslaw Jan Czedekowski (1885 - 1969). Joining American revolutionaries from 1776, made a brigadier general & US citizen in 1789; twice leading Poles against the Russians, their prisoner until 1796. Later friends with Jefferson (the great man's slaves benefactors of his will), he died in 1817, buried in the cathedral at Krakow. |

The Polish people most certainly have a subject. A distinct national culture for more than 1,000 years, they have often been seen less as a nation than as "The Polish Question."

Since the rise of abstract logic as the authorized mechanism for apprehending the world, many of us have been seen as a Problem -- requiring a Solution. Varied lives are cast as one, made neatly singular by the definite article: "The [fill in the blank] Question." (That blank is reserved for minor if irritating departments of reality. For instance: "Woman.")

Poland rose, like most nations, as a convergence of local tribes, the Polanie chief among them. Their first recorded ruler, Mieszko I, accepted Christianity in 966. Later rulers were often beholden to the Holy Roman (in fact German) Emperor, the kings of Hungary or Bohemia, or were set upon by Teutonic Knights. From 1333 Casimir the Great extended his realm, won international respect and, in 1364, founded a university at Krakow. *

Marriage linked the Polish crown to Lithuania; in time this dual Commonwealth (usually just called Poland) was one of Europe's largest states, encompassing Poles and peoples beyond, among them the biggest Jewish communities in all of Christendom. They often gave their rulers a rough ride: parliamentary traditions go back to the first Sejm of 1493, its two houses reflecting what the English called Lords and Commons. High culture flourished, the gentry (if not the peasantry) prospered; the 16th century was Poland's golden age.

It was not to last. Stephen Batory, a Transylvanian prince made king in 1576, had to fend off Ivan the Terrible. His successor faced the Swedes, who saw the Baltic as their private lake. Polish rule spread southeast into Ukraine, beyond Kiev. Farther south sat the Ottoman Empire: war with the Turks came in 1620, the Poles standing their ground.

They would lose it later, back up north: in 1655 the Polish Commonwealth ceded control to the Swedish Crown. In the dynastic dance of the Seven Years War, Russian and Austrian troops moved freely through. So did counterfeit currency floated by Prussia's Frederick the Great. Poland had become "a wayside inn" for massive imperial armies.

Six years after that war's end, their sovereigns decided to keep them there: in 1772 the First Partition saw a third of Poland's land and people swallowed up by its neighbouring empires. The reduced Polish state survived -- in surprisingly good health. The Great Sjem of 1788 launched sweeping reforms: by 1791 Poland had Europe's first modern, written constitution.

It was too much for autocrats east and west: Catherine the Great and Frederick (Great too). In 1793 they annexed more of Poland to Russia and Prussia; three years later, with Austria, they'd take the rest. The Hapsburgs, Hohenzollerns, and Romanovs did not (as was the custom) tack the conquered turf onto their royal titles. Even in name, Poland disappeared.

|

The Polish Question's

Final Solution Adolf Hitler's Table Talk

When Germany occupied Poland in 1939, heavily German areas were annexed to the Reich. More than a million Poles & 300,000 Jews from annexed lands were herded with the rest into what was left: the "Government- General," run by trusted Nazi Hans Frank.

In Oct 1940 Frank got his orders from the Führer -- delivered, as they often were, in "conversation" over dinner (of course carefully vegetarian).

"The Poles, in direct contrast to our German workmen, are especially born for hard labour. ...the Polish landlords must cease to exist, however cruel this may sound, they must be exterminated wherever they are.... The Government- General should be used by us merely as a source of unskilled labour.

"There should be one master only for the Poles -- the Germans. Two masters, side by side, cannot and must not exist. Therefore all representatives of the Polish intelligentsia are to be exterminated. This, too, sounds cruel, but such is the law of life.

"It will be proper for the Poles to remain Roman Catholics; Polish priests will receive food from us and will, for that very reason, direct their little sheep along the path we favour."

The SS, under Heinrich Himmler, were Hitler's chosen instrument of the Final Solution to "The Jewish Question." Frank saw to the Poles. As Alan Bullock wrote: "Poland, in fact, became the working model of the Nazi New Order based on the elimination of the Jews [the first death camp was at Oswiecim, Poland: Auschwitz] and the complete subjugation of inferior races, like the Slavs, to the Aryan master race represented by the S.S."

|

But for the Duchy of Warsaw (a minor fief created by Napoleon, passing on his defeat to Tsar Alexander of Russia), it would take 123 years for Poland to reappear on the map -- put there, with not a few other Eastern European states, by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

Hitler would soon see to all of them: Austria first, then Czechoslovakia, Poland invaded on September 1, 1939. Sixteen days later the Red Army rolled in from the east; by the 28th Poland was gone again, divvied up between them. When Hitler and Stalin fell out in 1941 it became a battlefield between them, no mere "wayside inn" this time.

In 1945 Poland was back on the map, if shifted west: Stalin's new allies let him keep his half, giving the Poles what had been far eastern Germany -- much of it, historically, Prussia. Many Germans would long insist it still was. Those allies also tacitly recognized a Russian "sphere of influence" including Poland, power politics trumping its historic links to the West. By 1948 it was total control, if by puppet governments.

Control sometimes slipped, reasserted by force, most famously in 1970, again in 1980, in the Lenin shipyards at Gdansk. The rise of Solidarnosc would not be squelched, in time helping fuel popular uprisings across Eastern Europe and the "velvet revolutions" of 1989.

Poles since, and their neighbours too, have faced modern consumer capitalism's shock therapy (less a shock to those left employed, still able to consume), the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank their potential rulers. But the Polish people, again and at last, have a chance to make Poland their own.

Poles, hugely, have a subject. And its stories. Thaddeus Kosciuszko battling Catherine the Great in 1792, leading the lost Insurrection of 1794. Risings in 1806, 1830, 1846, 1848 -- two of those dates marking democratic upheavals across much of Europe.

The January Uprising of 1863; revolution in 1905, when Russia rose too. The Warsaw Uprising of October 1944, doomed when the Russians checked their advance on the city, freeing Germans troops to crush the Poles: 210,000 were killed, all but 10,000 civilians. (The 1943 rising of the Warsaw Ghetto is seen, by some, as another people's story.)

Handed losses by history, people quite often prevail by means more subtle than force of arms. Polish literature has long been rich with elaborate allegory, sly allusions, veiled meanings; much of its theatre tends to satire; its films are often deeply layered with darkness and light (traits shared by their neighbours under totalitarian rule, most notably to Western eyes the Czechs). Art and literature have been the lifelines of Polish nationhood, especially when there was no Polish state -- a fact not lost on Hitler, Bismarck before him, or the Russians later.

Poles made Prussian by partition ever faced German Kulturkamf; Hans Frank took orders from Hitler to wipe out the Polish intelligentsia; Communist bureaucrats happily funded quaint "folk culture" while forcing the Russification of daily life (a tactic some Poles would see, more subtly applied, as "New Canadians"). Only in Galicia, held by the (necessarily) "multicultural" Austro- Hungarian Empire, were Poles finally left alone to be Poles.

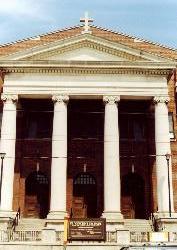

For many the key Polish bastion has been the Roman Catholic Church. Not all Poles are Catholic; for a long time many were not. But the Holocaust and the expulsion of Germans west, Ukrainians east, after World War Two made the historic Polish mosaic nearly all of a piece in ethnicity, language, and religion. In many minds, to be Polish is to be Catholic.

Polish nationalism could be liberal, international in outlook, most notably among social democrats. But even they (like later national liberation fronts) could tap nativist sentiments. Marshall Jozef Pilsudski, guiding light of Poland reborn in 1919, began as a democratic socialist; by military coup in 1926 he became a virtual dictator. Wladyslaw Gomulka, leading an "international" Communist government, did not blanch in 1968 at blaming its troubles on Jews, few as they were by then.

With their patron saint Mary, Mother of God, the Vicar of Christ since 1978 Karol Wojtyla, once archbishop of Krakow, many can share "a Messianic vision of the Polish nation," a mystical "Christ of nations, redeeming all oppressed peoples through its suffering and transcendence." Talk about a story.

It's hard to close the book on that one. Even if titled with a touch of irony, as at least one historian has tried. His major chronicle of Poland: God's Playground.

|

Monumental Poles

Resolute railway builder Sir Casimir Gzowski remembered on the lake; Nils von Schoultz on Bond: dissolute Rebel? |

Immigrant narratives, like the tales of any tribe unsure of its social standing, tend to the Great Man (or, if rarely, Great Woman) School of History: "one of us" who -- by dint of true grit, noble character, hard work -- made good.

Poles in Toronto can point to a monument standing by the lake west of Parkdale, marking a park named for Sir Casimir Gzowski. His great grandson Peter is now more famous: journalist, broadcaster, via CBC Radio's Morningside everyone's favourite avuncular smoothie. His (very public) loss to lung cancer in early 2002 led to tributes much fitting "one of our own" -- "we" being Canadians Polish or not, if especially "we" of the nice Canadian media.

But Casimir in his day was equally famous, master of the 19th century's most powerful medium: railways. Among his was the Grand Trunk. In the endless contention of rail magnates and the City over whether the lake shore would be for people or trains, Gzowski once threatened to run his line right down the middle of Queen Street. A colonel in the militia, he was named aide de camp to Queen Victoria in 1879 -- hence Sir Casimir.

It is sometimes wise to be wary of monuments. Gzowski's is backed by others, the Grand Trunk aside: six harbours on the lakes; famed bridges; the Burlington Bay Canal. He built them (or rather, had others build them) in his earlier career as Superintendent of Public Works for what was, from 1841 to 1867, the united Province of Canada.

On another, behind William Lyon Mackenzie's house on Bond Street, we find names of the heroes of the Rebellion of 1837, among them (apparently misspelled) Nils Sczoltevski von Schoultz. He and two fellow Poles are also honoured on one near Prescott, Ontario, unveiled in 1938 by the Polish consul general for Canada: "To the Immortal Memory of Polish Patriots Who Fought in The Battle of the Windmill, 12 - 16 November 1838."

That battle had been the Rebellion's last gasp. Defeated in both Lower and Upper Canada, its leaders had fled to the USA -- where they'd kept the flame alive. Some 300 Rebels (most American) crossed the St Lawrence that November, declaring a point of land, marked by that windmill, The Republic of Canada.

They had expected popular support. They got the loyal local militia, British Army regulars, and the Royal Navy. After 130 were dead, on both sides, the Republic surrendered. That skirmish has been called the "Alamo of the North" -- by those who, like so many Canadians, find our experiences real only when backed by American referents.

Among them: a historian who, writing of this battle in 2001, called Mackenzie "an arrogant little puff- toad of a man," those tardy Rebels a band of "the lazy and crazy," and Nils von Schoultz -- their accidental commander, others having fled the field -- a deadbeat dad and inveterate liar, "nothing more than a well- bred confidence trickster."

Nils was among the 11 Rebels hanged. Then: others had been before, still others transported to penal colonies in Australia. That's history for you.

|

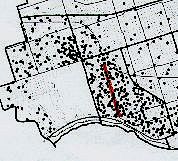

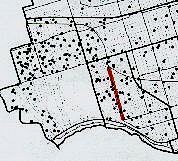

Still neighbours

Polish (top) & Ukrainian in Toronto's west end (Roncesvalles in red, the gap to its west High Park): one dot for each 15 speakers of the language. Both Poles & Ukrainians live in smaller numbers elsewhere but, like many European migrants in this town, their moves have been mostly northwest. From the City of Toronto's Mother Tongue Atlas, 1991. |

|

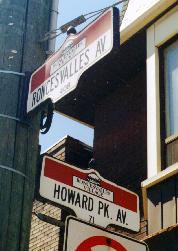

Almost Boustead

And another streetcar route: Howard Park Ave, north on Roncesvalles, taking the College car to John Howard's High Park. Boustead is the first stop on the way south from the Dundas West subway station for cars heading down to cross Queen & become the King car. |

But for having fled Poland in turmoil (both were rebels in the Uprising of 1831, though Gzowski had once been in the Russian army), Nils and Casimir were anomalous immigrants. They arrived alone, or nearly, not in the company of a larger influx. And like most migrants of the time they were men, married or not often leaving families behind. For a time. Or maybe for good: many hoped, once they'd made good, to go home.

The first cohesive community of Poles in Canada had left Prussian occupation in 1858, settling in Renfrew, Ontario. Many others set out for the West, often to set up near Ukrainians -- neighbours before and, like them, familiar with tilling the land. Few came to Toronto until the 1870s, most still men, peasants turned urban labourers.

Some rented rooms, in time houses to hold families, from another people they "knew rather well": Jews, in The Ward and along Queen West nearby. Many -- like Jewish immigrants before and most newcomers since -- were eager to buy a house and did, European immigrants usually west of crowded downtown.

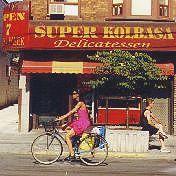

By the late 19th century signs of Polish settlement were visible along Queen, west from Spadina to Dufferin, likely destination for those newly arrived in the early decades of the 20th. Many more would come after World War Two, more again during the Polish upheavals of the 1970s and '80s. Not a few come still.

With each wave since 1945 came fewer who thought themselves peasants, more people urban, educated, technically skilled, professionally trained (if with credentials often not honoured in Canada). Fewer headed out West, more settled in cities. For many, as one of the 1980s told historian William Makowski, "all roads seem to lead to Toronto the Good."

Most headed for turf where the western spread of Polish community crystallized. It did not stop there (as you can see in a map of mother tongues at the left). But there they established institutions that survive even as many Poles have moved on.

It is a pattern characteristic of urban migrations: people making spaces their own, meeting their needs, reflecting and reinforcing community. Even for those who don't live there anymore, such places remain very much "downtown."

Ukrainians took much the same route (if leaving fewer signs along the way, some still on Queen and elsewhere). But the non- official language most spoken in this neighbourhood now, after Polish, is Chinese. Like all good downtowns, Polish downtown is shared. Roncesvalles Avenue, along with its town, is home to ever shifting stories.

Which brings us back, at last, to "Ronci."

Andrew Pawlowski, born in Warsaw, came to Canada in 1973. A doctor, his practice around Roncesvalles, he also sculpts. And writes: "many articles on art and artists in the Polish Canadian press, and five books."

The Saga of Roncesvalles he also published, in 1993. It is led off by the familiar parliamentary letterhead: Jesse Flis, MP for Parkdale High Park, here backing application for a 1991 grant to cover translation, photography, and printing:

- "I feel his book will be invaluable, not only to the people that live in the area, but also those who come here to shop, dine in the fine restaurants, attend services at the five churches, and enjoy the unique atmosphere of Roncesvalles Avenue."

Mavens of heritage ever love what they call "cultural tourism." MPs, it seems, do the spiel nearly as well as its current reigning masters: condo realtors.

Still, I am glad Dr Pawlowski (apparently) got his grant. His saga has less to say about "fine restaurants" than what came before them, his "unique atmosphere" the air of real life, present and past. He has a fine eye not just for what is, but what was, for how neighbourhoods evolve. He is no tourist, nor a tour guide, but a citizen alive to his locale, savouring its many stories.

My favourite marks a distinct moment, on March 23, 1988: "I noticed a fat man sitting on a post at the corner of Wright Avenue and removing a street sign.... After a short exchange, during which my interlocutor put up a new red and white sign (not to be confused with white and red, which would be in keeping with the Polish ethnic character of the area), we came to an understanding." Andrew got the old sign, a shot of it on the cover of his Saga. I got to find out when the City decided to mark Roncesvalles a "Village."

Pawlowski's "TTC romance" was set on a streetcar coming south. We'll head north from Queen, noting some of his stories along the way -- after a few tales marking the place where Polish downtown begins.

Roncesvalles, Pawlowski reminds us, is a name borrowed from a gorge in the Pyrennes -- Spanish site of an Irish soldier's British adventures against the forces of Napoleon. The avenue's intersection with Queen opens to Lake Ontario, a pedestrian bridge on the south sweeping over rail lines and highways to its (at last) unimpeded shore.

Just west of the approach to that bridge stands a chunk of pink granite, inscribed in Polish. It has a plaque attached, mostly in English. In a grove of trees beyond a dark monolith rises, its back to the traffic, two flags flying beside, Canadian and Polish. Walk up along King and you'll see its face, fractured and blank. Across its base, often obscured by wreathes white and red, is a single word: KATYN.