|

Promiscuous Affections A Life in The Bar, 1969-2000

1992-1995:

|

|

Boys of St Joseph

|

Kelly made his living showing off, & loved it. I once took him home for a "private show." The sex was nothing special -- but for the kissing: "Not bad," he smiled, "for an amateur."

The talk, all about him, was worth every cent.

1992

January through June

Colby's had risen from the remains of Katrina's in 1986, famous for shows -- not just drag but minor spectacles: choruses of queens, an MC in tux and tails and the "Flashdancers" in G strings.

In time that faded away, only those near naked boys still there, performing on a stage that after 9 pm was the dance floor. When not on stage these boys roamed around, chatting up customers and asking if they wanted a "table dance."

Unlike that strip bar I'd been to in Montreal, these dances were not at tables (there weren't any) but up on bleachers around the dance floor or in any convenient corner. The fee was $10, the usual tip on stage two. At night the A Team, hunkiest of the lot, were upstairs, leaving the younger, smaller B Team boys to work the main bar until 9:00.

Upstairs there was a back room for private encounters, no booths, just a room, later a bigger space with chairs scattered around. On stage (or pole; there were two on the bar downstairs, here one on a platform), dancers were not allowed to take everything off. In that back room they might, and might in fact do anything one desired -- and the dancer would allow. These were guys, strong, you didn't mess with them.

Many were not gay but that didn't much matter. Whether out of pecuniary interest (extras were extra, not stated; one needed the courtesy to know) or more rarely his own desire, a boy might happily strip, work himself up and, with just a quick check around, let his cock slide past some happy patron's lips.

Among them: mine. One sweet blond was very polite: "Do you like to suck?" I said I did; he obliged. Another had his own desires, a small boy, French someone said, from Paris and about to go back, this his last working night. I'd no sooner sat down than he'd stripped, climbed up, grabbed my head and wrapped my face down on him, so avid I thought he might come.

He didn't; in my experience none did. One boy did tell me had, three times. Maybe it was just promo -- if tempting nonetheless.

***

One dancer I'd known for years had perfected this routine even out in the open. He'd find a corner where he could stand on the arms of a customer's chair, put up a leg for cover, leave his shorts on -- all apparently innocent to anyone looking -- and yank up a leg of fabric, wresting his cock out underneath.

He did that with me, grinning, aiming at my mouth. I was amazed but of course opened up. Once initiated I could tell when he was happily face fucking others.

My favourite (and hardly just mine) was Kelly. I had followed his career since the late '80s, once literally, when he escaped Colby's for a brief stint at Zone 1, a small, two storey space across from Chaps at 16 Isabella. It was likely more lucrative, private dances there $20, but didn't last long: opened in April 1991, it morphed into a club called Rounds, then a restaurant, and then to obscurity. By then Kelly had long been back at Colby's.

There, up in front of me, he liked flexing that obscure if wondrous hip muscle, the tensor fasciae latae: he'd worked hard to develop it. He was always genial; then, on stage, on his rounds, his smile a wonder. Dancing on the pole he'd catch my eye and laugh, a laugh that said: Isn't this silly?

It was. But it was also amazing. He was small but beautifully developed, strong in difficult moves, graceful, controlled; I once told him he was an artist. He liked that.

He loved showing off, made his living doing it. And he loved to talk. I would once spend much more on him than usual, taking him home for what these boys called a "private show." The sex was perfunctory (but for the kissing: "Not bad," he smiled at me, "for an amateur"); the talk, all about him, was worth every cent.

Kelly made a lot of money. Most of the time. When not he went off to do something else he did very well (so I gathered from his rambling yak): paint houses. Sometimes I'd see him in mufti on the street, often with his dog. Or his girlfriend.

***

By the beginning of this year ACT was taking a toll on me. We'd just been through a messy hiring process, a job where HIV positive status seemed a likely criterion filled by an HIV negative lesbian.

The HIV Caucus questioned the decision; the Women's Caucus replied (we verged on management by caucus, identity based; there was Black Caucus of two). "What we heard," they wrote, "was a challenge to the role of women here, a challenge to the legitimacy and ability of anyone other than a gay white man with HIV to do AIDS work with ACT."

Thus was anyone with HIV defined as "a gay white man" -- a term often followed by "of privilege." That was hard on one worker HIV positive: white, yes, but female, heterosexual, and hardly "privileged."

It was hard on anyone not fitting the facile frame of who had HIV or AIDS: gay men (which in this town was overwhelmingly true) -- therefore white and well off (which wasn't).

Along with such inevitable politics, I had too much on my plate. We were planning a computer network that I would have to build and run, though I didn't yet know how. We were looking for a new office, our lease at 464 Yonge due to expire in December, and I got involved not only in scouting space but in helping staff figure out what it should be like, and why.

I was deeply into policy development, in part to guide our new executive director, Bob Martel, hired in September 1991. Bob was a genial, middle aged gay man ("a nice roly poly queen," someone once called him), but his social service background didn't include dealing with a politically articulate, self empowered staff.

After a meeting on that hiring flap he came into my office and said: "I don't get it! Tell me what's going on!" I did, on various issues, in talk, on paper; I was famous for long memos. But he didn't like to read. Bob had no focus and couldn't help me or anyone else find one. My mind needed sense; my body did too.

- January 22, 1992, to Jane:

I've been to PJ Mellons a couple of times in the last while, for the first time in a while. My wonderful jug eared boy Gary hasn't been there but Murray [another favourite waiter] was, and both my long absence and whatever it is I project these days -- weariness, I think -- completely changed our relationship. Instead of his campily morose banter about the state of his sex life (which I'm sure goes on well enough -- but he wants a love life), I get solicitousness.

I act as if I've been ill, move as if I still might be, feel fragile. I went to The Barn three weeks ago and after an hour and a half said -- fine, that's enough. I did get a wondrous moment by the dance floor, the kind you've heard about so often, finding one or two men to love on sight and loving all of us together like that. I can still feel that. But something has changed.

***

In February I asked for a month off and got it. My symptoms were worse by then: weakness, headaches, tremours. But what these might be symptoms of, I didn't know.

Neither did Dr Rachlis at Sunnybrook. She thought it might be myopathy (general muscle deterioration, not rare in people on AZT) or something neurological. In March I had a CAT scan, later an MRI scan. The high technology was lots of fun, but showed nothing unusual.

I had an ophthalmic exam, a lumbar puncture -- the dreaded spinal tap, but it wasn't all that dreadful. In the end the diagnosis was tentative: possible aseptic meningitis. That was good enough (along with AIDS) to qualify me for Unemployment Insurance medical benefits, giving me up to 17 weeks off if I needed it.

In the end I didn't: I was back working part time by May, by the summer full time again. But I did love that break.

***

But if dying is to become an ordinary part of life, it can't put everyone's life on hold until it's over.

There was one thing I did want to work on during that break. Michael Lynch had left one further legacy, not of his life's work but of his dying and death.

In late 1991 Andrew Johnson, Yvette Perreault and I discussed creating a care team manual, based on the one we had developed working with Michael, that might be of use to anyone dealing with dying at home. Andrew would write it, I would edit, design, and do some writing too.

There was a lot of material on palliative care, but mostly aimed at professionals in institutional settings. There was very little to guide ordinary people helping someone die at home, telling them what kind of resources they'd need, where they could get help and, most of all, that they had the skills and the power to do it.

In an early memo on the project I had written: "Our goal is to take back illness and death from the realm of medical mystery and professional control and return them to where they belong as ordinary parts of life. The modern Western world has taught us that we're not competent to deal with death. That robs us of power, a fully human power we need to reclaim."

***

The manual wasn't a rule book ("there is no one right way of caring for someone who is dying," its intro said) but a guide, flexible enough to meet widely varied circumstances. It was loose leaf, so people could add whatever they needed.

Michael Lynch, Jane Rule once wrote, had a "kingly death" -- with lots of people to help, a big house to accommodate them and still allow privacy, ample money and a university benefit plan to provide more. Not for everyone would it be like that.

But many of the lessons we learned with Michael could be more widely applied than they generally were in dealing with death. Andrew and I emphasized two of those lessons, if potentially contradictory ones.

First: the person in charge is the person who is dying, deciding in so far as possible what should or should not happen. Second: care givers had to take care not only of that person, but of themselves and each other.

If dying were to become an ordinary part of life, it could not put everyone's life on hold until it was over. That might not be for a long time, a prospect that could make people shy away, leaving others overburdened. The key was letting people in on practical things they could do -- errands, shopping, banking, laundry; not everyone is good at hand holding -- and telling them it was fine, even necessary, to set limits on what they could not.

I had seen and would see again what I came to call "the tyranny of the dying," if luckily in only small ways. Even at the end of life one is still in life, always a matter of civil negotiation, not of ordering others around -- if you want them to stick around at all out of anything more than guilt.

***

A hard lesson for anyone unwell can be precisely that civil negotiation: asking for help with things you could once do -- and want to do -- on your own.

Ed Jackson said when I went off work that he could never quite trust I would ever say I needed anything. Jane wrote: "You must make a simplicity of asking when you want help [a skill she had learned from her own often disabling arthritis]. I did not like the possible irony of you dropping dead alone in your room while completing the Care Team Manual."

Yvette had noted the same irony. I did plan to work on it at home, but after five weeks of staring at the dead computer screen, I knew I would not. Yvette was glad I had the sense to let it go. Andrew was also understanding if less sanguine, very busy otherwise and not always well himself. He had lupus. But he plugged on aided by others at ACT, and by 1993 it was done, published as Living with Dying: Dying at Home.

I may someday need it but, cussedly independent as I am, haven't much thought about it.

***

We were like that, all of us, didn't gush: once when I thanked Paul Pearce for all his lovely dinners, my words embarrassed him.

Kevin Orr was in and out of town often during this time, from Ottawa. He'd been working on contracts there but that was done, his apartment given up, staying with a series of friends. His life was up in the air pending his departure for England.

He'd got his ticket but then found his passport had expired, so there was that to fix and then his immigration interview at the British High Commission. Kevin was often a bit scattered. His desk at ACT had been one of those classic pile ups so vast it slid over onto the floor. "Don't worry," he'd say, "I know where everything is." He'd later admit that wasn't always true.

I had learned with Kevin to let such things go by: he'd cope and I didn't need to fret. We'd known each other now for more than 10 years, such close friends that we hardly considered it: each for the other was simply there.

Once on a wander with me Kev bought Luc Sante's Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York, a wonderful book. I know because he gave it to me, right there -- "Here, this is for you," he said, $40 and his cash flow wasn't good then.

I said to Jane: "On our walk that Sunday, looking at buildings and boys, it didn't occur to me how little we might see each other after that, maybe not at all given England for him, uncertain prospects for me. But he was thinking that. He'd never say it, but that's what the gift of that book was about."

We were like that, all of us, didn't gush: when I once thanked Paul Pearce for all his lovely dinners, my words embarrassed him.

On May 12 I went with Kev to Pearson International, getting there early enough to sit in a restaurant, watching flights land and take off. One of them was Kevin's, a British Airways 747 coming in at 6 pm for a turn around leaving at 8:00.

I joked with him I'd tell friends I'd seen his plane -- and that he wasn't on it.

***

I had been out to bars almost not at all since booking off work, not even much in the few months before. The Barn was nearly dead until far too late for me, Colby's had lost its appeal (temporarily), and I didn't much feel up to it anyway.

Only Woody's could offer a comfortable beer or two and that best in the afternoon, when most of the people there were staff I knew and enjoyed. I was there once in the evening, in May, with Gerald Hannon -- unusually: Gerald rarely went to bars.

But it was a small celebration: he'd just won a National Magazine Award, his second. The first, silver, had been for an article in Toronto Life on art critic John Bentley Mays; this one was gold, with a $1,000 cheque, for a profile in the same magazine on native playwright Tomson Highway.

Gerald hadn't bothered with the awards gala the year before but this time he went, with Robert Trow, both giddy as his name was announced. He was at last making (most of) his living by his pen, appearing often even in The Globe and Mail with pieces that would not have been out of place in The Body Politic.

Quite by surprise -- if with a characteristic "woof" -- we were joined at Woody's that night by Victor Bardawill. I hardly ever saw him any more but Gerald did: little Victrola was teaching voice, Gerald one of his students. He looked to me much as he had more than a decade before, boy small and twinkly and odd.

***

|

Ritual sites

|

Our need to mourn in such numbers is chance, but the way we do it, miraculously, is not. It's who we have always been, but too rarely got to be.

On a Saturday in June I was at Woody's again, this time for an event that might seem unusual but increasingly was not.

- Monday, June 15, 1992, to Jane:

Before that [dinner with Paul and David] it was two rather different memorials. Humberto Pierrera, a waiter at Woody's, died two weeks ago, and as the staff have done before they not only went to the service the family arranged (pleasantly surprising a Portuguese clan by their sheer gay numbers) but set up a section of the bar with food, snapshots, donation bowls for ACT and the PWA Foundation.

It's very casual -- but as I write this I'm suddenly moved by it, by us, by how we are. I had a beer, I talked to friends who were better friends of Humber than I had been; it went by me then, the bar goes on as usual and so did I. But now suddenly I can't see for tears (this is a surprise to me; so this is how it comes? -- so rarely): it was mentioning those donation bowls.

We seem to know so well that we do this for each other, that a life and a death is about all of us. What a wonder we turned out this way: not that we have so many to mourn, but that we do it so well. Our need to mourn in such numbers is chance, but the way we do it, miraculously, is not. It's who we have always been but too often didn't get to be.

***

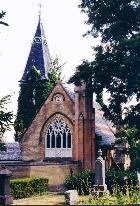

The other memorial that day had been more traditional, at the chapel in The Necropolis where, for Andy Armstrong's in 1987, I had stood at the door surrounded by men I knew from The Barn, many of them now at Woody's.

This time I didn't know most of the people there, many of them teenagers, students seeing off their French teacher. Some spoke, trying to call him Mr Stephen but sometimes letting slip Donald. I had known Don Stephen and his lover Richard Mehringer casually for years, mostly through Gerald.

In 1978 in The Body Politic, he had done a photo essay on them and their life as a couple -- decidedly not monogamous but very much together. He had ended it with a bit I've never forgotten, playing on Ezra Pound's instruction to his poems: "But, above all, go to the practical people -- / go! jangle their doorbells! / Say that you do no work / and that you will live forever."

- If we can be disruptive social poets with our lives (I think we already jangle more than their doorbells!), we can go to practical people, practical men who have married practical women to raise practical children for a practical world and we can say, "Not only are we going to live forever. We are not going to live like you."

I hadn't seen much of Don in the last while but I did see Richard: he had been on Michael Lynch's care team. The memorial was a chance to see him again, and Don's mother too. I had met her on Galiano; Don had grown up there. She and her husband, Don and Richard, Jane, Helen and I had all had dinner there once.

On that visit or perhaps one before I had wandered through the island's small graveyard, finding two plaques in a shaded grove, their dates telling me both had died young men. I didn't recognize the names. Only later did I learn that one was Don Stephen's brother Robert, who had also died of AIDS.

In Jane's next letter she told me she'd had a call two days before, saying that Michael Wellwood -- that fellow guest on Galiano in 1984; he'd later been in Toronto and worked briefly on TBP -- had died at St Paul's Hospital in Vancouver. She wrote:

- You deal at close range with so many deaths, so much mourning. I understand your saying that you often feel numb, are curiously grateful for the moments when grief returns. Here there's nothing to do with it. ... There is a mounting anger I don't know what to do with; so I turn away, read and read.

***

Kevin wrote in mid June to tell me he was learning the distinct cruising techniques of London bars (the quickest simply a blowjob in a dark corner) and to say that the life of Three Queers and a Baby on Kilburn High Road was going fine.

"Sam is a very sweet boy," he said, "and I'm surprised at how ma / paternal I can be." I sent back tales of a few other sweet babies.

- To Kevin Orr, Sunday, June 28, 1992, 9 pm:

Sunset on Pride Day, probably the most perfect Pride Day there's been: cloudless but only 25 degrees (and last weekend it rained and the high was 10) -- and I'm sure the biggest Pride Day this town has ever seen. I'm waiting for the news now to see if they'll tell me how many people were there -- but I won't believe any figure under 100,000. I think there were even more.

Lots of the floats had music (even ACT's); the bar ones were each followed as ever by about 1,000 gyrating bar boys (and girls -- tell Gillian this town is now full of randy baby dykes in leather) and on almost all of them there were drag queens frozen in overdress and all your favourite bartenders and go go boys wearing almost nothing.

White Calvin Klein boxer briefs with short legs and revealingly loose crotches were very popular this year. That wonderful hunk Ted from Woody's was in them, and a very hot boy who once danced for me in the brief period when you could get boys to dance for you at The Barn, downstairs. (I'd tipped him for a public show and he said, "But you should get me to table dance, I get a hard on when I table dance" -- and he did.)

But my favourites were two boys dancing on the back of the Power float, both in yellow hardhats and tight little bathing suits. These two used to live in my building, lovers, both tiny perfect hunky buttons. Catching them in the elevator on their way to sun in Cawthra Park, dressed as they were today less the hardhats, was all the sex I needed (or heaven knows might get!).

Watching all this wondrous half naked flesh on wheels round the corner at Carlton and Yonge, blocked off by police and bordered by crowds six deep, the air filled with disco and flying condoms and bubbles I thought: just imagine -- they block traffic to open the streets for the life we know in bars.

It was quite a celebration, perhaps the first here to edge beyond "Lesbian and Gay Pride" to something more encompassing. Joan Anderson, with whom I was out in it all, noted more visibly heterosexual couples than ever before, looking not like tourists but participants.

The Grand Marshalls leading the parade (just behind the traditional dykes on bikes) were a contingent of Children of Lesbians and Gay Men, Stefan Lynch one of its organizers. I saw a girl in a T shirt that read "Gay man trapped in a woman's body" and a boy, clearly a boy, in one that read "Lesbian." As I said to Kevin, "Maybe we're approaching true queerness."

That queerness even encompassed AIDS. When the head of the parade reached Bloor and Yonge the entire procession stopped, the music went off, and like a wave moving back down the route people sprawled on the street, drag queens and pretty boys alike laid down on their floats -- an AIDS "die in," a full minute of silence in the midst of all that joyous noise.

It was sudden, even shocking -- and very powerful.

***

|

Street vice

|

Vices once kept behind closed doors now needed only a railing between them & unlicensed pavement. On Church, the street itself had become the scene.

More scenes

For other photos of the area, from 1997, see Church & Wellesley: Photos in the CGLA site.

Most relevant here: shots of Church & Wellesley's four corners & The Churwell Centre.

Spot demographics

More on Church & Wellesley on the CGLA site has lots of census data on Tract 63 (Yonge - Jarvis / Bloor - Carlton), 1951 to 1991, Some highlights:

Households. In the metropolitan region on average, about 80% of dwellings held a traditional family; more than half were occupant owned. In Tract 63:

Age. Overall, a third of the population was under 20; another third 20-39.

In Tract 63:

Gender. In general, females outnumber males. In the tract, in a key age group:

So: fewer families & children, more young adults, more living alone -- & many more renting -- than in the rest of the metropolis. Peak census year for these trends: 1981. The slow rise in kids & homes owned continued with the 1996 census, reflecting the area settling down -- & more condos. But still very male: in 1996, more than 60% of residents in Tract 63, age 20 - 39, were men.

One person households / Rented (% of total dwellings)

1961: 44.2% / 91.1%

1971: 54.2% / 97.9%

1981: 69.7% / 97.3%

1991: 67.4% / 93.4%

Under 20 / 20-39

1961: 10.6% / 40.6%

1971: 7.2% / 56.0%

1981: 4.2% / 60.6%

1991: 5.7% / 57.0%

Age 20-39: Male / Female

The life of the bars was more than ever out on the streets, and not just on Pride Day. When Woody's opened in 1989, many patrons hadn't wanted to sit near its front windows, feeling too exposed. Now in good weather those windows were flung wide open, people practically hanging out of them.

It was the same down the street at The 457. Bar 501, opened in 1990 just up the street, also threw back its big panes, drag queens there aiming their performances not just into the bar but out onto the sidewalk, often drawing a good crowd -- and noise complaints from nearby highrise tenants.

Pints, a restaurant at the corner of Church and Maitland, opened around the same time, its long street side patio with a back deck under a marquee soon rivalling The Steps at The Second Cup as the cruisiest spot in town.

At the opposite corner was the Queens Dairy, aptly named even when it was a classic greasy spoon, now rebuilt as the Unicorn Family Restaurant (less apt; it became The Village Rainbow) with vast windows in front often open, a once vacant patch along side become an outdoor eatery. There was another one right across Maitland, flanking the more upscale Vagara Bistro.

Along the front of the Churwell Centre (stretching up the west side of Church from Maitland to Wellesley on what had been mostly a parking lot; its 1984 opening had revitalized the street -- and given us The Steps), Ciao Restaurante set a few tables in its small space out front. Il Papagallo, later Café California, put out many more in a courtyard next to a lane to its north. Across the lane Toby's, a local burger chain named for a real if deceased local dog, had an even bigger outdoor space.

North of Wellesley the Dundonald Pub had a patio wrapped round it; its duplex neighbour restaurant had one out front. Later, when Partners film company left the area, vacating a number of street front spaces, some became gay bars. One was Sailor, right beside Woody's, joined to it inside and like Woody's with its big front window often thrown open.

Across the street was Crews, in a rambling Victorian house. It was pressed almost up to the street but even there a tiny deck was tacked on.

***

All this would have been illegal until quite recently in this town. Sidewalk eateries had been allowed by city bylaw only in 1968, serving booze in them not until the next year.

But now it was another city: vices once kept behind closed doors and darkened windows, if any windows, needed only a railing between them and unlicensed pavement. The life we knew (or some of it) in gay bars and restaurants -- many of the latter, Pints for one, not opened as gay but soon made so by their clientele -- was now very much out in the open. At least in good weather and especially on Church Street.

The street was a magnet for money. Alex Korn had hung onto Chaps up on Isabella, but it was doing less well now, certainly less well than Woody's. Power, the place those cute hardhat baby buttons had been promoting on its Pride Day float, had opened in April as an attempt to revitalize Chaps, its second floor turned into an even hotter dance palace done in industrial high tech. Colin Brownlee, who knew what worked in bars and clubs, seeing so many as Xtra's ad rep, had advised on the design.

But this time it didn't work. Power failed and was replaced by Badlands, Country & Western moving upstairs with downstairs renamed Neighbours (once the name of a restaurant on Church, later Windows on Church and later still Slack Alice).

In time Alex sold the place to the owners of P J Mellon's. It soon faded, the space turned over to a 24 hour grocery. Alex would find a safer investment back on Church Street, opening Sailor next door to (and in fact an extension of) Woody's in May 1994.

***

Gay bars did survive off Church. Derek Stenhouse and René Fortier, founders of The Manatee, had opened Soltero's in January 1987, advertised as "gay built, owned and operated."

That "built" may seem odd, but they'd done it all themselves, proudly, as they had at 11A St Joseph in 1970 -- giving this new place much the same feel. It was over storefronts on Yonge but entered by a stairway at the back, on Gloucester Lane; it later became The Cockatoo; still later The Web.

The space at 11A St Joseph had briefly been Chez Z, more drag, but became The Playground, with go go boys (shades of the old Manatee), table dancers (many from Colby's right next door) and a maze called "The Toy Box" with private dance booths.

Its original promo line, "When the boys go away, the men come out to play," was soon dropped: the players at The Playground were nearly all boys, even boys with girlfriends.

Trax still held its spot on Yonge as did Boots over at Sherbourne and Selby and, much further afield, The Toolbox way out on Eastern Avenue.

But some of these places seemed marginal not just geographically but in style, catering to specialized tastes (at The Toolbox, regulars could get snippy about "downtown boys" dropping in as tourists) or to clientele younger or older -- and often poorer -- than the increasingly homogeneous homo "mainstream" at Church and Wellesley. Some could feel like gay bars of old: isolated, almost covert, the scene inside them rarely apparent from the street.

On Church the street itself had become the scene, the whole area visibly gay. Rainbow flags were soon a fixture not just on Pride Day but all year round, flown outside bars, restaurants, and the many small businesses -- grocers, butchers, galleries, tchotchke shops -- eagerly appealing to gay customers. There were soon only a handful left on the street that did not.

From Bloor down to Maple Leaf Gardens even the lampposts were festooned with rainbow banners, courtesy of the local business association.

There's no mistaking here that you're in gay downtown. The area has not only an unofficial mayor (or two) but an official, openly gay city councillor. In 1991 Kyle Rae, among the organizers of the first post bath raids Pride Day in 1981 and later director of the 519 Church Street Community Centre, had run in Ward 6 -- the same seat contested by George Hislop in 1980 -- and won it. (He's won it ever since.)

***

There remained some confusion about what to call the neighbourhood: Church & Wellesley (accurate if not very snappy); The Village (favoured by those business types); or simply The Ghetto. Crews briefly housed a dance spot called "Ghetto Fag."

Not everyone was amused, aspiring to a more respectable image. While vibrant, Gay Main Street would grow gradually more uniform, predictable, safe.

To find real ghetto fags of the sort I'd known for so long, one increasingly had to look, as ever, beyond Main Street.

Go on to 1992: Jul-Dec / Go back to Contents

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1992a.htm

January 2000 / Last revised: October 8, 2001

Rick Bébout © 2001 / rick@rbebout.com