|

Promiscuous Affections A Life in The Bar, 1969-2000

1992-1995:

|

|

ACT scouts new digs

|

The vast majority of people affected by AIDS here were still gay men. It was important to be where so many of them lived.

1992

July through December

Back at work and feeling up to it again, I was caught up with Bob Martel, Ruthann Tucker and a real estate agent in our search for the AIDS Committee of Toronto's new home -- not, we discovered, a thing easy to find.

Four sixty four Yonge wasn't far from Church and Wellesley but did not feel of it, just 200 yards making the difference between gay downtown and the roaring main street of the entire city. ACT's work wasn't just for gay people, of course; some said it wouldn't matter where we were located.

But it did matter: the vast majority of people affected by AIDS here were still gay men. ACT was no longer the only AIDS game in town: there were groups working with the Black and Asian communities; existing agencies seeing immigrants, young people, and women were also doing AIDS work. So was the city public health department, one of their projects The Works, a mobile needle exchange to reach IV drug users.

ACT worked with them all, had even helped launch some of them. It might have taken another tack: trying to be the One Big AIDS Service for Everyone. Some wanted us to be, citing liberal notions of diversity, outreach, inclusiveness -- noble concepts that can come to mean tokenism, colonization, control: Welcome to my world; now here's the rule book.

We knew there was no such thing as a culturally neutral "social service"; knew that the health of communities had to be the work of communities, speaking their own language, figuring out how to meet their own needs, owning AIDS for themselves. ACT could and did work with them -- offering information, advice, even money -- but we could not do it for them. It wouldn't work. We had learned that working with the community we knew best.

ACT was still one of only two groups in the city -- the Toronto People with AIDS Foundation the other -- growing from, rooted in, and working primarily with the gay community. It was important to be there, physically and visibly.

***

But the neighbourhood offered few options. Spaces that were big enough to house more than 30 staff, hundreds of volunteers in and out, and the PWA Foundation as well (they'd been at 464 and we wanted to stay together); that were physically accessible, as 464 clearly was not -- and that were affordable -- were rare.

We looked for ages, finding narrow hallways, tiny washrooms, very few windows. One place looked good; we got so close to a deal that we did floor plans for it. Then the deal fell through. It was frustrating: the disheartening tours; the haggling; the plans laboured over only to be abandoned -- and Bob Martel.

Bob was the ostensible link between ACT's volunteer board of directors, who would have to make the decisions, and the real estate agent, Ruthann and me, doing the legwork. But he was ever in a dither. In a tense meeting someone hinted this big messy process needed better direction. Bob snapped: "I am in charge!" -- proving he was not, and knew it.

At that meeting he said: "I've just written you a nasty note." I looked puzzled. "No, not you personally," he said, "the HIV Caucus." We'd sent him a memo on that lone woman with HIV, now working not full time but hourly. Could she still come to caucus meetings on paid time? Her supervisor wasn't sure.

Bob said she shouldn't -- but it was up to her. It was classic Bob. His "nasty note," scrawled on that memo, returned to us, said it had made him "doubt your commitment to improving the condition of people with HIV at ACT" and that he was "tired of having to account to the HIV Caucus."

Bob's defensiveness would become chronic, his mood often so sullen that even Ruthann, his own executive assistant, hardly dared speak to him.

***

|

Boys of St Joseph

|

The boy didn't know how to hustle business, so I tipped him $5 on stage. He wore that bill wrapped around his G string the rest of the afternoon.

Some might have been surprised that he had, in his little butt pack, a licence to hunt moose.

I did try talking with Bob, learning it was best to leave issues aside and just let him yak. I told Kevin Orr (who got all my ACT gossip) I'd done it one day and made a surprising discovery -- if not one about Bob.

- Thursday, August 6, 1992, to Kevin:

Bob must have liked that talk: at 3:30 he came in and said, come on, let's go to a movie. Socializing is not what I need from him, but what the hell. Still, I didn't want a flick. I suggested we go have a beer at Colby's instead.

After staying away for six months I've been back at Colby's a few times lately. I'd resolved not to part with any cash except for beer -- unless someone was truly fabulous -- but oh, slippery slope, today I did. Not much, not while Bob was there and not, I must admit, for someone truly fabulous. Just someone sweet and skinny and hesitant, truly touching: he didn't even know how to approach anyone for business.

I had a hard time getting his attention so ended up tipping him $5 while he was dancing on stage. He wore that five dollar bill wrapped around the band of his G string for the rest of the afternoon.

He's scrawny but not ratty (nice haircut), has a trim triangular head, serious little features, ears that stick out and despite the skinniness a nice, smooth biteable bum. Not that I bit. I may -- but he looks like that might scare him right out of the bar.

His name (what can I say?) is Ricky.

That was Ricky's first day at Colby's. I found that out only later, dropping in occasionally after harried days at work for a beer and, if I had the right day, for Ricky. He did do private dances for me -- as private as any dancer could be there, out in the open, who didn't have particular skills. I'd be in a chair or on the bleachers, he up on a little box.

His favourite move (or so it became when I told him I liked it) was to crouch in front of me and wrap both hands around the back of his neck, elbows out, bringing definition to his biceps, shoulders, chest. I'd caress them, his legs, his back, his face, never his crotch. Outside the second floor private backroom one didn't, and Ricky hadn't graduated to the upstairs A Team.

In one of our first encounters he said he wanted to. "But I have to gain some weight first." I said I liked him just the way he was. He said thank you and smiled. It was the first I'd seen that: a quiet, slightly splay toothed smile lighting his serious face just a bit.

Our dances, so called, usually ended with him in my lap, his head resting back on my shoulder and his legs sprawled out. Once like that he got an erection, the stiff ridge under his tiny satin skivvies embarrassing him as he got up.

***

I loved touching Ricky, but soon those dances were as much about talk as touch. He told me he'd be 20 in November and I thought of myself at 20, in The Parkside, nervous, the drinking age still 21 then -- and he then not yet born.

He was from a small town near Georgian Bay, had left when his father kicked him out for wearing an earring. He told me once he'd just been back to have it out with his parents about being, as he said, bisexual. It didn't go well.

A hunting trip with his father was due but Dad had told him it was off. Ricky said he would go anyway. It might have surprised some in the bar to know that one of the things in the little butt pack he often wore (and which I'd hold for him when he danced on stage) was a licence to hunt moose.

- September 19, 1992, to Jane:

I've escaped work twice in the past two weeks for Colby's and little Ricky. After six weeks there he's less baffled about his professional role -- so much so that a week ago Friday he was too busy to find me for anything more than a hello.

I sat with Norman Hatton, a photographer in his fifties, a man I've always liked and often find there. A friend of his came by as well and ended up ogling out loud the boy performing on the floor: Ricky. I was amused at my sense of protectiveness (possessiveness?). Ah, but it's best the boy be popular.

I think he really does mean bisexual. He has a boyfriend now ("Did you see him? The guy I was kissing over there?" I hadn't), but a girlfriend too. "I think when I really want to be intimate I'd rather be with a girl. Do you think that's weird?" Well, I hadn't put in 15 years of work in gay liberation to have a queer little kid like Ricky think he's weird. "No," I said, "I think that's great."

He danced for me later, working too hard at it. I slowed him down, just held him, cupped his neck, my thumbs on his cheeks, and told him how much happier he seems now. I wish it hadn't been so dark in that corner: I really wanted to see that smile.

He told me he wants to finish high school. It will be hard: his concentration is bad; he doesn't like reading: it makes him sleepy. But he likes football and hopes to play. "Football?" I said. "Yeah. I'm small but I'm a good runner." So, a skinny little running back -- with an after school job he's afraid he'll have to keep secret.

Yes, I'm smitten, in my avuncular way. I told Paul and David about Ricky [and Kelly; I'd taken him home just before] and Paul said, "You're always looking for the prostitute with a heart of gold."

Put that way it can seem quite banal. It is, in the sense of being ordinary, silly romance. It's not really prostitutes I'm after -- though I know I like the lack of complication involved, my life being complicated enough; like the simplicity of boys whose primary interest is pecuniary and whose interest and openness beyond that, if you can get it, is a gift.

***

Found -- & nearly perfect: 399 Church St, ACT there from Dec 7, 1992, its sign not until 1999. |

At last we could create a truly public space people could explore on their own -- browse, read, even sit quietly on their own -- instead of just sitting, bored, waiting to be led off to the inner sanctum.

We called it the Access Centre.

On September 22 we finally nailed down a deal on a new office for ACT. It was at 399 Church Street on the corner of Carlton, a bit south of the ghetto's main action but you could see it from The Steps.

It was new, built in 1984, with ground floor retail and three floors above. We'd take the top two storeys, the PWA Foundation most of the second; there were some common meeting rooms there as well. To afford it we'd need to find other tenants for a small part of the third floor. The board was nervous at that and at the cost in general -- the rent was higher and there'd have to be renovations -- but in the end we convinced them.

"We" were mostly Ruthann and myself. She and I did budgets, worked out logistics. With board members I cooked up a special face to face donor drive, The Builders' Fund, to help finance it. And -- in endless consultation with other staff -- I did floor plans.

The building was nearly perfect, not only for all its glass and light, its six fully accessible washrooms, its elevator for human beings, not freight, its three steps at the entrance, not 464's 26, those soon bridged by a ramp -- but also for its separate storeys.

ACT had spread haphazardly through the single floor at 464, with little thought for public amenity. Counselling and meeting rooms were far from the entrance, a long trek past private offices.

The Resource Centre, which had grown from a shelf of books and a few files in Ed Jackson's office to a vast collection meant for public use, was off the lefthand door at the top of the long flight up from Yonge -- but you might not find it: the reception area was off the door to the right.

People there played "receptionist" in the usual fashion, paying most heed to the jangling phone; other staff and volunteers zipped through madly, that small space the only route between the two office wings. People coming to ACT just sat there -- as they might sit in a waiting room at a doctor's office or a welfare bureau: bored, nervous, maybe flipping through an old magazine.

Waiting was all they could do. The space told them they had no power to do anything else until one of those important people rushing by stopped and led them off to the inner sanctum.

***

From mid 1991, when we first knew we had to move, I'd been pondering how we might avoid in a new space anything as intimidating, as demoralizing, as that traditional "reception" area.

The model that came to mind was a public library, where you could walk in, move freely around and find all kinds of things on your own, asking for help only if you needed it. Over time -- and with not a few memos -- I got others hooked on the idea.

Betty Ann Rutledge, an insightful young woman from Winnipeg, worked reception and knew how awful it could be for people forced to wait there. Mark Rabnett, also from Winnipeg and a cutie of the bookish sort, ran the Resource Centre, eager to find ways to make it more accessible.

Dave Doig, originally from Vancouver and a cutie of the bar sort (you'd think, though he rarely went out; his lover John Russell was also on staff) did ACT's brochures and fact sheets, hoping to make this quick info available to people as soon as they walked in.

Janet Rowe, hired in that messy flap in January and surviving it to become one of ACT's best counsellors, wanted to ensure that people walking in needing more than information could get it -- right there, from staff and volunteers trained to judge needs, meet them if they could, or connect people right away to others offering more specialized advice or support.

We came up with concepts for how all this might be made to work in a new space. It had to be a clearly public space: not mixed up with private offices; not full of people rushing by ignoring anyone who came in the door. It had to be at the door, the first space anyone coming to ACT would see.

It had to be big, inviting, encouraging people to explore. They shouldn't feel under surveillance but should be able to spot those who could help them, who could bring skills upfront from ACT's deeper reaches, offering basic information and support themselves rather than being mere "receptionists" routing human traffic to this department or that.

No one walking (or calling) in should have to know anything at all about ACT's various bailiwicks, for so long such separate and defensive fiefdoms. Step inside and you'd be at ACT, a seamless whole (at least apparently so) ready to meet your needs.

***

Of we five coming up with these concepts, two things were of note: we came from across those different bailiwicks; and none of us was a manager. Our ideas grew from the bottom up, crossing fiefs in a way rare for ACT at the time.

We had to work hard to sell those ideas, to the management team and to other staff. I had taken the lead but in time could step back, Betty Ann, Mark, Dave and Janet firmly committed and pushing hard to see their vision realized.

In time it was, 399 Church with its separate storeys helping make it possible. The third floor went to non public functions. On the fourth we left offices at one end; at the other we tore them out, making a big open space.

With ACT's relaunch at 399 Church on December 7, 1992 (after a hellish move and a week there before construction was done), people coming in rode the elevator to the fourth floor and stepped out into more than 1,700 square feet of fully public space.

Quick info was right by the door, books and periodicals a few steps away, in depth subject files off to one side. Help was at hand but unobtrusive, an information desk off to the other side, not stuck smack across the entry. Deaf Outreach and the Women and AIDS Project were nearby. There were places to read, some private, a place to view videos, places where one could sit out of traffic -- and wait if one wanted.

But the space gave people the power to do much more than wait. It was North America's biggest public AIDS resource, counsellors available just down the hall. We called it the Access Centre.

***

I've gone on a bit much about this space, I admit, even spaces in general and the uses we put them to. I've always been a frustrated architect, drawing plans since childhood.

But of all the things I did at ACT I feel best about the Access Centre, its space consciously shaped to give people a bit more power over their lives.

I was smart enough not to try making it happen alone, trusting the strength and intelligence of others taking power on their own. Mark Rabnett went back to Winnipeg, Dave Doig stayed on until 1999, Janet and Betty Ann still there, having survived even greater messes at ACT which, in the end, I would not.

The Access Centre is still there too, renovated since, but with its guiding principles largely intact. It now has more than 4,500 books, 1,000 detailed subject files, 900 videos, 100 periodical titles and a terminal for online access -- all available to anyone who walks in. In 1999, more than 11,000 people did.

***

|

Big boys of St Joseph

|

Announced as Chad, he had an accent Eastern European. He was Slovak -- so likely not Chad.

On the stages of strip bars (not just gay ones) you could see a veritable parade of people displaced by world politics. I'd later find Polish boys, & Russians.

I sometimes went to Colby's when Ricky wasn't there, at night and upstairs for the A Team. This was Bachelors, opened in July 1990 and touted then as "the first tobacco free bar in the city." That distinction soon went up in smoke. The name survived, if more in promo than common parlance: to most it was just Colby's, upstairs.

Most of the boys there seemed not boys, still young if not as young as downstairs but very big, some hugely overdeveloped. They looked like Chippendale knockoffs -- not the furniture but that famous troupe of hunks who strip for women. Their routines were hypermasculine, heavy, rigid: on stage they could look like furniture.

Most of them treated their bodies like machines, butch poses alternating with "sexy" moves that, ironically, seemed lifted from female strippers: butts stuck out and slowly stroked; tongues circling their lips; baskets jiggled instead of tits.

Perhaps that was the only model they knew: many of them were straight, many professional, some represented by an escort service called All Class Males, others by Top Guns.

Their routines were not at all sexy to me, nor I imagine even to themselves, unlike some of the more sensual, less self conscious kids downstairs who, sometimes, seemed to take genuine pleasure in their own moves.

Still, inside these hunks one could sometimes -- if briefly; the place was less conducive to casual chat than downstairs -- find something of a person, a bit of his story.

***

Even if not, the scene could be interesting. I'd been for dinner at David and Paul's one October night, bringing as usual $10 in lottery tickets: for Paul; I never played. He paid me with five $2 bills. I decided to spend them upstairs at Colby's. Two bucks was the standard on stage tip; I could spread my largesse with abandon.

I suspected the place might offer an odd spectacle that night: the Toronto Blue Jays were playing the final game of the World Series, their first, the city already going mad. I was curious to see what that bar -- an odd enough gay bar at any time -- might be like when live attractions had to compete with a televised spectacle of ostensible heterosexuality.

In fact, they didn't even try. The game was on there, dancers too rapt to care if anyone was watching them. Not that their income suffered: at 1 am, after 11 innings, the Jays won -- and everybody cashed in on everyone else's good mood.

I found a boy I'd tipped on stage, introduced as Chad. I asked him to dance for me. He had an accent; vaguely Eastern European. It turned out Chad was Slovak -- so probably not Chad.

He didn't take his tight shorts off during our backroom session but did later find me and say, "If you take me home I take my pants off." I enjoyed that moment, but declined. I did later get the pants off his younger brother, stage name Aaron: less bold, but he liked to cuddle.

On the stages of strip bars (and not just gay ones) you could see a veritable parade of people displaced by world politics. I'd later find Polish boys, and Russians. They would all soon get an accidental raise, the $2 bill replaced by a coin -- not the kind of currency one could slip into skimpy attire.

After that the least courtesy one could offer was five bucks.

***

Sightlines, Oct 1991; coverboy & centrefold Tony: "His 38 inch inseam rises to a crotch that encases all the history of his Metis / Iroquois background." |

It came to be run by people connected with bars, promo disguised as a magazine.

One was a partner in Colby's -- so Colby's dancers featured large in Sightlines.

Some of these boys could also be found in a magazine. Sightlines had been launched in 1990 by Owen Haywood, best known as founder of JOLD. It stood for Jocks or Leather and Denim; Colin Brownlee said it really meant Just Old and Looking for Dates.

They did The JOLD Awards, honouring the community's best social group, sports team, bartender, drag diva, whatever. JOLD's honours were later overtaken by the Pink Trillium Awards, doled out in annual ceremonies -- notorious for running longer than a night at the Oscars -- by the Trillium Monarchist Society, TMS, later TICOT, The Imperial Court of Toronto.

Such "courts" had been common out west, each year electing an Emperor, Empress, and their whole titled retinue. Back east we'd found it a bit odd. But by 1987 Toronto, too, was caught up in campaigns for royal titles, monarchs and their courtiers touring the town, doing it all for charity.

Drag queens, even those not of the blood, were the community's most avid fundraisers, always mad for a gala benefit. One of them, "DQ," put on to support Casey House, became for some years a major event.

Sightlines was full of court doings, promo for royal candidates, ads for Bar 501, Rawhide (still going if soon to go) and Colby's, among an eclectic mix of editorial content. It came to be run by people connected with some of those bars, their promo thinly disguised as a magazine.

One of them was George Pratt, once of The Albany and The Toolbox, now a partner in Colby's -- so Colby's dancers featured large in Sightlines: on the cover, in multiple page spreads, naked in most shots, with erections in some, and always with a little story, often by George Hislop.

It was Sightlines that told me my dancer Tony was 23, six foot three, 170 pounds; that his "38 inch inseam rises to a crotch that encases all the history of his Metis / Iroquois background" (so much for Russian); that he'd been a meat cutter in Montreal and liked Dobermans, horses and Lamborghinis. There were nine shots of him, the loveliest capturing his big smile.

***

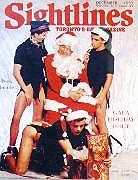

Cover boy: Ricky! Santa George & friends, Dec '92 issue. |

"He's getting good at what he does. Watching that I beam. Now he beams back.

"We spent four songs together; I still have the smell of his armpits on my hands. It's the way I get to take him home."

-- to Jane, on Ricky,

December 1992.

Sightlines would poop out in early 1993 but did manage to give its last few issues full colour covers. The December 1992 number featured Santa Claus with three half naked elves.

It was George Hislop decked out as Santa, three Colby's dancers as his helpers. I knew Pedro, sucking a candy cane; George liked to call him the Portuguese Prince (or Princess, depending). And I certainly knew another. It was Ricky.

- Wednesday, December 2, 1992, to Jane:

Here is his picture, the one on the left with the long, coltish legs. I heard a lot about this photo shoot before I got to see its results. It doesn't look much like him but for the slight bend in the nose (he broke it when he was about six) and the ears that, even in profile, you can tell stick out.

He was lovely and silly on his birthday last Wednesday, drunk on two Sambuccas (somebody said he'd like it) and as many beers. Generally he doesn't drink, but it made him smiley, flirtatious (with everyone) -- even improved his dancing -- but then made him yawn.

I did contribute to his boots [he badly needed a new pair and I'd said I'd help] but today found out he hadn't bought them; it all went for food and rent. Credible enough: from 3 to 7 today he made all of $2.

Still, he was up today, his hair down, a great sexy mop as he danced to Madonna's "Erotic." And very erotic he was. This self conscious skill is new and a pleasure to me even though, as you know, it was his reticence that first made him attractive to me. But you also know how much I like competence, in anything. He's becoming very good at what he does, and watching that I beam. Now he beams back.

We spent four songs together later; I still have the smell of his armpits on my hands. It's the way I get to take him home.

Kevin Orr was back in town for a few weeks in November and on one Saturday I took him to Colby's, to see Ricky. It was slow; Ricky stood talking with us for quite a while, more affectionate with me than ever. When I stroked he'd stroke back, snuzzling his head down onto mine, even brushing my lips with a kiss -- only the second and the first had been just the week before.

He seemed very happy that day. I told him so; he looked away, smiled, in wonder or embarrassment I'm not sure. "Yeah," he said, "I am." It was nice to see one of his regulars, he said, Saturday not one of my regular days.

He had only one other so far, a big genial man who stuffed bills into the back of his G string; nice he said, "but they itch my bum." That man later turned his affections to a blond named Chris. I liked Chris too, but he wasn't Ricky.

***

In my last letter to Jane this year, still frazzled from ACT's move and with 117 hours of overtime, I wrote:

-

I want to get some time off and get the apartment back in order -- my metaphor for getting myself back in order. The place is dusty, supplies spotty; I'm ratty and need a haircut and would like to start caring a bit more how I appear to cute dancing boys. Not that they care how I look, really, not even Ricky.

But he does care that I'm there. He says so. I tickle his ears with my moustache, telling him I love to see him smile -- and he says: You always make me smile.

Go on to 1993: Jan-May / Go back to Contents

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1992b.htm

January 2000 / Last revised: October 8, 2001

Rick Bébout © 2001 / rick@rbebout.com