|

Promiscuous |

|

Adventures in small business

The Upper Crust

"Rat race dropouts":

|

Rosedale ladies complained about the prices. Forest Hill princesses didn't care what anything cost as long as it was the latest thing: "Is this one stone ground?"

I learned that while poor kids get sniffles, rich kids have allergies -- to everything; learned that the more people worried about what they ate the more pinched & paranoid they became.

I was reminded Hitler had been a vegetarian.

1976

For my 26th birthday in January, Bill and Jacques in Ottawa gave me a small, nicely bound book, full of blank pages. They wrote in the front: "A new page... A new book." I used it to make my only journal entry of the year.

January 31, 1976:

I'm not sure I can deal with the lack of lines.

It was one afternoon after a management study meeting, in which I tried to push an idea for a very confrontational newsletter, that I realized: this place's ultimate weapon is that it makes one begin to doubt oneself instead of it. Anger turns inward, turns to guilt. I did almost quit on the 23rd. The story is too much to go into, but the important thing is, being that close was practically a liberation. I had made myself accept the idea -- I can quit. No big deal.

And so I will, I've pretty much decided, June 30. Jane [Cooper, head of the management study] asked if I'd run for [university] Governing Council, and I said no, citing the fact that I really did intend to go. Five years, more or less by accident. I want to work in a place I can believe in. Again, dumb. But I may have educated myself out of anything less.

I remember the exact circumstances of that decision: I was clearing out the night return book bin, slogging volumes onto a cart, then stopped and said to myself: Enough of this. No more. With the freedom of those who have nothing to lose, I got very mouthy.

The strike had ended in December, the union winning little more than the university had offered three weeks before. But just weeks later the federal Anti Inflation Board, trying to wrestle the annual rate down from double digits to six percent, rolled back the wage settlement.

The union urged a one day sick call in protest; most members stayed home. I was told to call absent staff under my supervision and tell them they'd be docked a day's pay. Instead I called the head of personnel. He was a pleasant gay man; I liked him. "Donald," I said, "tell me what's going on. I heard the university is appealing the Anti Inflation Board ruling. Is that true?" He said it was. "Then why don't my staff know it?" "Because," he said, "Judy Darcy doesn't want them to."

With that I snapped: "What a load of shit!" -- and hung up on him. Judy was head of the union local, the university still timid enough to let her run the show. She was a stern Maoist then, likely not later: she'd become national president of the Canadian Union of Public Employees, on TV always looking quite elegant.

I went in to see the head of Sci Med. I liked her, too, but I was seething. We argued. Her final words: "I know how you feel but you have to make those calls." I said I would -- but that it would be the last thing I'd ever do there. She was quite taken aback. I stormed out and did the dirty deed.

That wasn't the last thing I did. I stayed a few months doing what I could to ease tensions that did indeed arise from the strike. I finally left on May 31. By then I'd had my last work assessment, a self appraisal, one's supervisor adding comments -- an idea I'd proposed in that leadership task force. I'd said my usual work had fallen apart while I was swamped in the study. The head of Sci Med said I'd been too hard on myself: "He has done very well considering the workload he took on."

That workload later wouldn't look so bad, considering what I came to take on.

I didn't have to look for a job: I had one handed to me. David Newcome and Paul Pearce had long baked bread at home, mostly to David's recipes or his mother's -- and to raves: "You should go into business!" People always say things like that with no idea what it means to start a business.

We had no idea either. But David quit his bank job, Paul and I put the library behind, and we were off. They would do the baking. I knew beans about bread but figured I could run a store.

So: some tales of life in small business. Planning and start up were fun, if at times harrowing. We rented space in an old building near Bathurst and King for the baking plant, and there our utter naiveté began to show.

We'd have to put a new chimney five floors up the outside to vent the oven. That we had in place, practically a room in itself, eight feet high and half again as wide, revolving shelves inside. It sat on a big concrete slab we'd poured ourselves. We were doing all the work ourselves, but for building that oven.

Then an inspector said we'd have to put up two layers of fire rated gyproc on the ceiling -- a maze of sprinkler pipes. That was the last straw. The oven guys knew another space, in a one storey, steel trussed, metal roofed industrial mall in far off Weston. I learned why those places look like that: they're built to meet all those fire, health, and safety codes we knew nothing about.

So, at some cost, we abandoned the downtown site. The pros came and took the oven apart, its ton of parts left all over, buried knee deep in scratchy insulation. We jammed masses of it into 100 green garbage bags, loaded them and all those huge, heavy parts into a rented truck, and carted it all up to Weston.

David drove at just 20 miles an hour -- lest we be crushed by that load in a sudden stop. Then he and I went back and broke up the oven's leftover slab, carting chunks of concrete to a landfill at the Leslie Street Spit -- bits of the biz already dumped in the lake.

But it turned out a blessing: that cramped space downtown was a 10th the size of what the plant in Weston would become. Things went better there, the three of us having a fine time. A favourite part of our day -- after slogging away on a "natural" bakery -- was to stop at McDonald's for Big Macs and fries.

Then David decided he could paint the ceiling of the plant himself. He always thought he could do everything himself. So in came a machine with a long spray nozzle hose. Up David went -- and down the paint came: red mist all over, big blobs plopping to the floor and all over David. Dashing into the back of our little truck he hit his head on the jamb, the blood lost in his now red hair.

Checking his wound I said firmly, "David, we're hiring someone to do this." For once he gave me no argument.

The store was at 1099 Yonge, one of a row newly opened south of the Summerhill liquor store -- a former CPR station with a tall clock tower, dating from 1915 -- upscale as government booze outlets go. The stores, in buildings even older, were to be upscale as well. In time the locals would call them "The Seven Bandits."

We built all the fittings, a long counter backed by wooden racks, the shelves canted to show off the goods. David's mother made curtains, lampshades, and aprons for the staff, all from the same green and white ticking. I did the logo, my first design job ever, choosing a typeface I thought rather bread-like.

David had come up with the name, apt for the neighbourhood. One wag later said we should open a day-old annex and call it "Down at the Heel."

The clientele, in truth, were hardly the masses. Many were genteel Rosedale ladies, some who complained loudly if perhaps half in jest about the prices. "Twenty five cents for a cookie!" one piped. (They were huge; I once wrote a promo line for a new variety: "Another cookie as big as your face.")

Forest Hill princesses didn't care what anything cost as long as it was the latest thing. Skeptically eyeing a loaf one asked, "Is this one stone ground?" Every baked item in the store was stone ground (or more accurately, its flour was). I learned that while poor kids get sniffles, rich kids have allergies. To everything: "Do you have anything with no wheat flour?" No corn, no milk, no eggs?

I learned that the more people worried about what they ate the more pinched and paranoid they became. I was reminded that Hitler had been a vegetarian.

Scores of people walked in with the same opening line: "Oh, it smells so good! I know! -- you bake it all right here, don't you?" Of course we did not. At least one man (there were few men) didn't say that, the aroma masked by his fat cigar: John Turner (we usually saw his much nicer wife) would later, if briefly, be prime minister.

So that was my life then, lone victim to whatever whim might walk in the door. I had to get there by 7 am to unpack all the baked goods carted down by Paul and David a few hours before. From 9 am to 6 pm, later on Thursdays and Fridays, I couldn't even go to the bathroom without locking the door. Then it was hours cleaning up, every day, six days a week.

I knew piss all about food. "What would be nice with a bouillabaisse?" one woman asked. Search me, I thought: what the hell is a bouillabaisse? Paul later said my suggestion (corn bread) had been apt, if accidentally.

Things got better when new bakers were hired, freeing Paul to join me at the store, at first just on Saturdays but then all week. His bright, challenging banter won over all the fussy ladies. We got a third counter jumper part time, a friend named Douwe, blond and playfully sexy. The three of us could have a great time -- with each other if not always with the customers.

But mostly I hated it.

I was too tired to go out, my only diversions Balfour Park a block away, the occasional cute customer (few gay, and those rather stuffy), and a skinny kid who worked in another store. His tight jeans displayed a meaty schlong, a few times on show out of them. Once after closing we played at the front of the store, he with his back to the window, I with his cock in my hand.

From bib overalls |

I quite liked being found by such a smart, good looking young man. Soon we were together whenever we could be. In September he moved in with me. We had become lovers, for each of us the very first one.

A few hours later he came back, the store busy by then. I kept shooting him glances that meant: "Don't go!" He didn't. He bought a loaf of black walnut bread (underbaked as it turned out); I said he should come back sometime.

He did -- just days later, arriving in the late afternoon, staying until I closed the store. I took him out for a cheap Hungarian dinner and then home to bed. He had never had sex with anyone in his life.

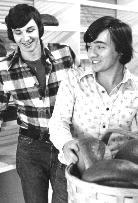

He was Brent Ledger, 21 years old -- and his sudden appearance no accident. Toronto Life, on its regular "Super Shopper" page, had done a small item on The Upper Crust. It included a photo of Paul, David and me in the store, the caption inducting us into small business mythology: "Rat race dropouts." Given our pace I found that a sick joke. Brent had seen the item and, as he later told me, figured I was "the gay one." One? Well, no matter. He'd come by to check me out.

I guess he liked what he found. And I quite liked being found by such a smart, good looking young man. Soon we were together whenever we could be, walking all over town, I with my camera taking endless pictures of him. He couldn't stay overnight, having to get home to his parents in Etobicoke, often heading back at ungodly hours.

In September we solved that: he moved in with me at my place on Sherbourne Street. We had become lovers, for each of us the very first one.

I was no less busy, of course. Brent was not, at the time mostly out of work. I would leave at 6:30 am, not get back until 9 pm, often much later. Brent would sleep late and then go wander. If I had been his entrée to gay life he soon needed no guide, doing quite well on his own. Pictures I took of him over time show a remarkable transformation: no more mop top, no more bibs, but a handsome young man impeccably groomed and knowing it sometimes too well.

I didn't much mind. He occasionally took pictures, too, Polaroid shots of his tricks, so he could show them to me. Quite nice, most of them.

By winter it got tougher. I'd leave home in the dark, come home in the dark -- to Brent just getting ready to go out. I did once go out with him, to Studio II at 72 Carlton -- an ironic venue: his father's office at Columbia Pictures was right over its door. I ended up in tears. From then on I never wanted to go out to bars with a lover and almost never did.

In time I'd trudge out into cold black mornings with Brent not yet home from his night on the town. Once while I was setting up the store an ambulance roared by. I shuddered -- unnecessarily of course, but he might have been anywhere.

Once I wangled a rare afternoon off. Brent wanted to go shopping, for a coat maybe, and a gold chain he'd seen somewhere. When I got home he'd just got up. We got out by 4:30. He bought nothing, the afternoon shot. I smouldered, he clammed up. Finally, to force something out of him, I hit him.

Three times, right there on the street: a kick, a swat, a follow up backhand. I was appalled: I'd never done anything like that to anyone. He froze up -- I swear he could suck tears back into his eyes -- and that night went to stay with a friend, his and mine, but Brent's trick then and not mine.

Later, in fights, I'd learn I could throw things. Brent could too, breaking through his usual repression in ways that, even in the midst of it all, could seem a wonder to me. We did always choose carefully what to send flying. For years I kept a small shard of a plate he smashed, a talisman of Brent unleashed.

My friends didn't always like him. Once after a dinner with Ed Jackson, Gerald Hannon and a few others, someone hesitantly said he thought Brent could be rude with me, his cleverness too snide. But that never bothered me: I knew the routine. It would go on for some time and, for all that, they were mostly good times.

I did love the boy.

But I didn't care -- about the possible money, about bread, about the whole damn thing. What did it mean, really? To me, nothing. I was there only because I cared about David and Paul. I wanted work I could care about.

I had put in one more toe with The Body Politic, modestly: a letter to the editor. In it I took to task Graham Jackson for comments he made about Frank O'Hara, his work included in a book of gay poetry Graham had reviewed.

Graham could be a dour fellow; he'd later become a Jungian therapist. A poet himself, he was also the paper's dance critic and an excellent one. We got on well: I'd visit him and his lover, dancer Michael Conway; in 1978 I'd give him a hand with a book of his essays, Dance as Dance.

But in the moment I did rather mind Graham claiming that Frank O'Hara had been a closet case. I refuted that, then wondered aloud "if behind this contention of closetry there doesn't lie the assumption that the works of gay artists must be obviously gay in content, and not just in style or point of view."

Frank O'Hara's poems are most obviously gay to me in their language, their awareness of small daily things [all those references I had found too "in" six years before], their occasional frivolity. Though they deal in things which are ultimately meant to be taken seriously, they do not do so by taking a solemn tone, by being heavy. He gets dismissed by a lot of critics as a lightweight for this -- they are used to sonorities.

We shouldn't be fooled. Heavies are easy to fake, and content can be tacked on. It's the point of view which should distinguish gay poetry. We should be able to see things in ways that straight people can't, and that's what should be obvious in the work.

The same old line, if not doing much with it. Ed Jackson had been. The Body Politic was now deep into cultural concerns, Ed getting reviewers and essayists from around the world to write for a small paper in Toronto. In its February 1976 issue he'd put together the first review supplement with its own title: Our Image. That little "gayrad" rag would soon be one of the most sophisticated and incisive sources of gay cultural analysis anywhere in the world.

Very soon now, I would join Eddie and many others in that work. I would find that while they certainly meant their work to be taken seriously, they were rarely solemn about it.

In person, anyway. In print it could be a different story.

Go on to Part Three: 1977-1981 Going in every day

Go back to: Contents page / My Home Page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1972.htm.htm

December 1999 / Last revised: June 16, 2003

Rick Bébout © 1999-2003 / rick@rbebout.com