QUEEN STREET

Parkdale

"The floral suburb"

French forts, sylvan speculations,

charming villas: from village to town

to city neighbourhood

|

Well, almost

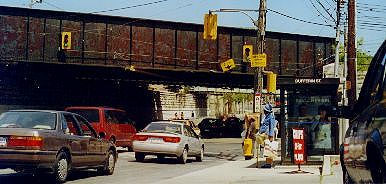

Greeting near the foot of Dufferin -- if on its east side, so not in Parkdale proper. Just south: French fort recalled in a mere bus loop, the arch of the Exhibition's Dufferin Gate beyond. |

|

Which Brock?

Modern marking of the village named (accounts differ) for either Sir Isaac, hero of Queenston Heights, or the less famous if likely related James. |

This place we call Parkdale lies not far east of another place -- this city's very reason for being: a place where waters meet, a river flowing into a lake. We call them now the Humber, and Lake Ontario. The Wendat, for whom it was the end of a trade route down from Huronia on Georgian Bay, called it "toronto."

In 1615 they showed that place to Etienne Brulé, then 23, scouting for Samuel de Champlain. Black robed missionaries and rowdy coureurs de bois would come to know well le passage de Toronto. The Wendat long had, the Senecas too, and the Anishnawbe (it means, simply, person; to the French they were Mississaugas). Dutch traders from the Hudson knew "the carrying place." English freebooters from Albany did too. All of them, Percy Robinson would write in 1933, "with or without license robbed the poor Indian."

In 1750 the French built a fort at the river's mouth. To secure its bay they soon built another, three miles east along an Anishnawbe lakeside trail. Both were often called le fort de Toronto. The newer and bigger was more formally named, by the governor in Quebec City, to flatter the Minister of Marine in Paris.

In 1759, with New France falling, Fort Rouillé was burned by retreating troops, leaving the British just "five heaps of charred timber and planks." A plaque marks the site, in the Canadian National Exhibition grounds just east of Dufferin Street. Just west, Fort Rouillé stands in name only, if likely seeing more visitors: its short stretch leads to a TTC bus loop.

The land between those two French forts we now call Swansea, Sunnyside, High Park and, rising above the eastern shore of Humber Bay, Parkdale. None of these names is native to its locale, nor even long applied. Least of all Parkdale.

Founding the Town of York in 1793, Colonel John Graves Simcoe doled out free land to his loyal retainers. The Park Lots, running north from a line at the bottom of the First Concession (now Queen Street), are best known for shaping development downtown. But they also shaped what would become Parkdale.

From 1797 to 1799, four 100 acre Park Lots in the First Concession, numbered 29 to 32 west of what is now Dufferin, two "farm lots" twice the size further west, and the "broken front" running south to the lake were all granted to soldiers who had served under Simcoe as Queen's Rangers. Like many of York's gentry farther east they did not live on their estates, happier to speculate in real estate. What they had got as gifts they or their heirs soon sold off, reaping 100% profit.

Among them was James Brock, of Guernsey, "apparently a cousin," historians say, of General Sir Isaac Brock -- saviour of Upper Canada in the War of 1812, falling (and monumentally honoured) at Queenston. James got lots in the broken front, "Commonly called Brock's Land" says a map of 1833. He also got Park Lot 30. Up it now runs Brock Avenue, originally Brockton Road, suggesting (as did many such names) that it led somewhere significant.

Brockton sprang up along what was at the time the most significant road west of town: Dundas Street. Begun in 1799 as military route set well inland for defence, it headed north from the First Concession line at what is now Ossington Avenue, then angled northwest. Dundas was a main highway, paved as the "West Toronto Macadamized Road" by 1833.

The other route heading west (variously named for where it led: Lake Shore Road, Burlington Road, Niagara Road) was often a bog. It ran dead straight along the First Concession line, called Lot Street in town, known beyond (and on some maps even in town) as the Road to Dundas Street. Or just Dundas Street -- if not the one we now know anywhere east of Ossington. In 1844 it would be renamed Queen, Victoria not so honoured in Parkdale for some years to come.

Before that, Dundas ruled. So did Brockton -- modest as it was, described by one writer in 1852 as "a cluster of houses, three of which are taverns."

|

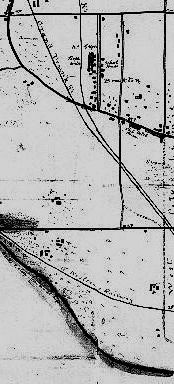

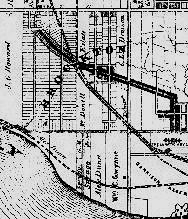

Realtors' dreams; rural realities Brockton rules (above), on a map of 1860, like many of the time showing lots laid out, packed tight along the diagonal line of Dundas St. The dotted lines are railways, two running northwest from Queen, one nearer the lake shore. Left: what was really there, in a military survey of 1863. Only Brockton Rd runs all the way from Queen to Bloor. |

On maps of the 1860s, Brockton's name covers turf all the way south to the future Queen Street. Its eastern boundary was set at Dufferin (north of Dundas anyway: the route south was long blocked by a swamp). Beyond sat the City of Toronto. It had pushed past Bathurst, its first western limit, to take in the lakefront Garrison Reserve; its "liberties" north to Bloor had been annexed in 1852.

The line marking Parkdale's frontier with its much bigger and sometimes cranky eastern neighbour had been set: that "Welcome" above is on the City's side of Dufferin Street. But, as you can see, Parkdale was not yet there -- except in the dreams of developers. As, perhaps, greater Brockton.

|

West Lodge then & now

Garden plaque for Colonel O'Hara, his military career (of "stirring & even romantic incident") giving us Sorauren & Roncesvalles. Shown here: his 1831 "oasis in a grand forest" -- now site of the West Lodge apartments, seen below from Lansdowne Ave. |

South of Dundas, wilderness long remained. That 1833 map showed Brock's Land "now clearing," the four Park Lots to its north "cleared"; west of what are now Lansdowne and Jameson avenues, the rolling land was "uncleared" or "yet in forest." But its clearers had arrived. Some have been recently recalled in gardens along Queen Street, each with a plaque put up by the Toronto Public Library and a local business group.

Walter O'Hara, born in Dublin, possibly in 1789, had "fought with distinction" in the Peninsula War in Spain, twice wounded. Coming to Canada in 1826, he was made a colonel in the militia. Six years later he bought Park Lot 31, settling there with wife Marian and an eventual eight children in a house he called West Lodge, known "for many years as an oasis in a grand forest."

The house survived to 1960, having served as "an asylum for fallen women" and a reform school for Catholic girls. It is now marked by avenues named O'Hara and West Lodge -- leading to a massive apartment complex.

In 1840 Colonel O'Hara bought two farm lots further west, flanked by avenues he named to commemorate his Spanish battles: Sorauren and Roncesvalles. In 1856 he subdividing the land between into 13 "villa lots." That same year son Robert registered "a plan of building and villa lots" north of West Lodge -- "at Brockton."

The Colonel's command of South Brockton (as it might have been called) did not extend south of what was then Lake Shore Road. There another Irishman would set up camp. Dr William Charles Gwynne, educated at Trinity College Dublin, had sailed to Canada in 1832 as a ship's surgeon. Once here he married well: his wife Anne was granddaughter of William Dummer Powell, chief justice under Simcoe (he'd got a lakefront lot downtown).

In 1840 the Gwynnes bought much of Brock's former Land, south of Lake Shore Road (now Queen Street) to the actual lake shore, west from Dufferin to Cowan Avenue. There they built Elm Grove, "a picturesque regency villa." Standing until 1917, it and its owners are survived by avenues: Elm Grove and Gwynne.

Doctor recalled: Plaque (left) marking the career of William Charles Gwynne, set on Queen at the corner of his avenue (below, left). Above: a stretch of Gwynne farther south.

Villas there were if only a few, more dreamed of in plans, anticipated on official maps. But none of those maps yet showed Parkdale. Development of local real estate didn't truly take off until these big estates lost their founding landlords.

Alexander Roberts Dunn, Dr Gwynne's neighbouring owner to the west (if an absentee landlord), died in 1868, Gwynne himself by 1875. Their families soon carved their estates south of Queen into lots fit for quick sale. After Colonel O'Hara died in 1874, widow Marian sold off the bottom 20 acres of Park Lot 31 (West Lodge included) to the Toronto Housebuilding Association. In 1876 they bought the top 30 acres of the Gwynne estate.

It was likely the Association, historians say, who first called the place Parkdale. Maps of Toronto are dotted with "-dale" ("a small valley," my dictionary tells me, "akin to DELL") and "-vale" ("Chiefly poetic A valley; a low-lying tract of land"); "-hill" and "-view"; Heights and Mounts; Woods, Groves, Glens. Parkdale is not alone in being named as a marketing ploy by agents selling small plots of land as "picturesque" landscape -- sylvan scenery, bucolic vistas, pastoral settings.

William Innes Mackenzie, the Association's secretary and leading light, is often called "The Father of Parkdale." "Through his exertions," an official biography of 1886 noted, "the town has risen from a mere hamlet to one of the finest suburbs of the city of Toronto." But it was not just sylvan speculation or poetic promotion that truly put Parkdale on the map. That was the work of forces more mundane, even grimy, if no less motivated by profit.

|

A movable seat

Waiting at Canadian National's Parkdale Station, shown here in 1957 -- not in its original location. For its travels, see the caption under the full image at the right. Below, South Parkdale Station: opened by the Great Western in 1879, taken over by the Grand Trunk in 1882, abandoned in 1912 for the GTR station at Sunnyside. |

- "At This Place on May 16 1853 The First Train in Ontario Hauled by a Steam Locomotive Started and Ran to Aurora"

Those words appear, under an engine named "Toronto," on a small plaque on the base of a pillar on Front Street, at Union Station. Not opened until 1927, that station was not there then; the city's first was, built by the Northern Railway in 1851.

That "little balloon-stacked engine" hauled four cars west on a line of the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railroad Company, with a slight curve crossing Queen Street at grade near the future route of Dufferin. It chugged past Brockton on its run north. But it would have more than passing impact on the turf it traversed. As The Story of Toronto tells us:

- "The first train had barely arrived at Aurora when a Toronto newspaper carried an advertisement of the sale of land around what was to be known as the Village of Maple."

Rails and real estate have long been connected: the CPR, on its way to the Pacific in 1885, got title to vast stretches of Canada along the way. This town's western reaches would see more than one railway company; some would own parts of it outright. But here it was their routes that would most matter: they shaped, even created, what was to be known as the Village of Parkdale.

Parkdale peripatetic: Built by the Northern Railway in 1878, this station sat east of Dufferin facing Queen from the south. Taken over by the Grand Trunk a year later, it was turned around to face their own tracks. In 1923 it passed to CN; in the mid 1970s they tried to tear it down. The Parkdale Save Our Station Committee raised money to buy it, moving it to Sunnyside in early 1977. There, eight months later, it burned down.

The Ontario, Huron & Simcoe line had severed Brockton's southern reaches. In 1858 the OH&S became the Northern, its line already paralleled south of Dundas by one of the Grand Trunk's, laid in 1856 to get to Guelph.

By 1878, Toronto Grey & Bruce and Credit Valley lines also ran along the same corridor, a formidable barrier for anyone heading north or south. Or east: all their tracks sliced Queen Street just east of Dufferin; the spot would be marked by key battles in Parkdale's future. Another barrier had been laid to the south: the Great Western Railway's tracks, run from Toronto to Hamilton in 1855, blocked easy wanders down to the lake shore. Parkdale had been hemmed in by railways.

But residents could hardly complain: for a time they were served by five companies in cutthroat competition. The Grand Trunk took over the Great Western in 1882, the Northern in 1888; in 1883 the TG&B and Credit Valley had been swallowed by the Ontario & Quebec Railway, itself consumed a year later by Canadian Pacific.

Even then travellers could choose among three stations, two northeast, one south. From 1886 they could also catch, every 10 minutes, the Toronto Street Railway's Queen car. Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific suburban trains could also take them downtown, from stations proudly signed, North and South, Parkdale.

There was a TSR Queen & Brockton car too, running up Ossington and Dundas to the senior burg. But no big rail depot was ever flagged "Brockton." In time, many in Toronto could not even say where Brockton might be. Quite soon, Parkdale would be much on their minds.

|

"Progress & Economy"

The Town of Parkdale seals itself, incorporating emblems of Village elders: maple tree for nurseryman & reeve; councillors' scales of justice (a barrister), book (selling same), quill pen (bookkeeper) & bull (a butcher). |

|

"Charming villas"

1889 manse on Dunn Ave, its owner's initial (H) laid out in roof tiles. |

|

Streetcar flats

Early 20th century apartments: on Queen far west (if maybe without a lake view); farther east with courtyard. Blocks more grand on King can be seen in the main tour of Parkdale. |

This place railways framed and realtors named soon boomed. An 1878 atlas of York County noted that Parkdale "has almost sprung into existence within a year or two, is rapidly growing and will soon become thickly inhabited and covered with charming villas."

Residents debated its potential fate, arguing among three options: staying a minor fief within the vast Township of York; annexation to the huge City of Toronto; or incorporation as an independent village. They opted for independence. Having reached the required population of 750 (by including "a tribe of gypsies" camped on a vacant lot; they later "folded their tents and left for what they considered safer camping grounds"), the Village of Parkdale was born on January 1, 1879.

Its borders were set at Dufferin east, Roncesvalles west, the lake on the south and the angle of tracks northeast -- if less than halfway north to Bloor: beyond was still Brockton, becoming a village on its own in 1881. By 1883 Parkdale had more than 2,000 residents, and petitioned to be named a town. In January 1886, it was.

The proudly independent town, like the village before, committed itself to "Progress and Economy." And no little respectability. A bylaw of 1879 had made it illegal to circulate "indecent prints or placards," "harbour bad characters," "keep a house of ill- fame," use "profane language," "behave in a disorderly manner," go out soused, gamble, or give "intoxicating drink to a child, an apprentice, insane person, or a servant (if forbidden by his employer)."

Laws to check the excesses of the "dangerous class" were hardly rare at the time (or since). Parkdale's particular wariness of the working classes was exposed in early bylaws meant to keep factories out of the neigbourhood. It was also an early bastion of temperance, banning booze on its birth in 1879.

Concern for Economy (over Progress of the moral sort) led village elders to relent: they needed tax and licensing revenue. By 1880 there were taverns again, in 1883 "only industries creating offensive smells" were limited, others offered incentives to move in. Workers moved in with them, some already working nearby. Until 1889 the CPR's locomotive shops sat just east of Dufferin. In 1886 the John Abell Machine Works had risen next to its rail yards; farther east, since 1879, sat the Massey farm equipment factory. Both would long be there.

Within its own limits, Parkdale tried to keep industry north of Queen. In 1884 the Gutta Percha and Rubber Manufacturing Company set up on West Lodge, "the only rubber factory in Ontario," employing 100 workers. Many would have been immigrants: Irish (if not so well off as their local betters); in time Italians, Finns, Macedonians, Poles.

But, even by then, a stove factory stood south of Queen just west of Dufferin. In 1889 the Toronto Radiator Manufacturing Company, moving from Niagara Street, took over the site's five acres, later adding more. Another 100 worked there. Most workers' housing was kept north, but some got in amidst villas nearer the lake. In 1882 the Toronto Mail reported residents south of King "highly indignant over the erection of one- storey cottages, running off Cowan Avenue."

| Affronting charm: Trenton Terrace, rousing indignation in 1882, now reclaimed as quaint. Right: Melbourne Place, "modest 2 & 3 storey" rows rising in the 1880s to flank "the narrowest street in Toronto" -- now perhaps the city's smallest gated community (if with no guard). The handsome streetscape nearby on Gwynne, shown above, also began as workers' rows: their roofs show no firewalls. |

|

|

With public transit (if then privately owned) came "streetcar apartments," blocks of three to five storeys rising along their routes, many still standing on Queen. Some on King were grand, if within the means of many on modest wages.

More people in Parkdale were workers or local merchants than "company owners or managers from Toronto who view the new suburb as an escape from the city's bustle and high property taxes." Most lived there all year round. Even so, a city handbook of 1884 noted that "the Parkdale neighbourhood is one of the healthiest and pleasantest for summer residences in the vicinity of Toronto."

Local forces were fond of such pleasantries, eagerly promoting them. Bylaws not only backed the planting of trees, bought with civic funds at $25 per hundred "to secure uniformity and beauty," but rewarded their vigilant defence: $25 was offered for snitching on anyone suspected of "malicious injury to any shade tree or trees in this village." "Unregistered dogs" -- if perhaps for more than their potential effect on freshly planted saplings -- risked being shot.

The Parkdale Register regularly lauded the "scenery of an undulating expanse of fertile country, wooded, watered, cultivated, and adorned with attractive homes," tempting Torontonians with the "refreshing coolness that is lacking in the close and sultry city." They touted "clean" industries, efficient transport -- and low taxes.

Parkdale long guarded the public purse, banking on private initiative: "each man," the Register emphasized, "pays for the improvements in front of his place alone." In 1887 the Parkdale Times offered a gloss on the town's lack of public parks: the place had "parks enough" -- "for almost every household has the little back yard turned into a park where the patrons can freely breathe the free air of heaven to their own satisfaction."

Toronto papers dubbed Parkdale "the floral suburb" -- often with less than kind intent. In 1881 the Mail, noting "weeds of every description in full blossom" on its unpaved streets, reflecting "anything but credit on the municipal fathers," jibed: "The 'flowery suburb' can dispense with the additional bloom."

Slick city scribes loved taking down "a village of very aristocratic pretentions" -- "austere, proud, and chaste," a place that "ostracised the saloon keepers, frowned on negro minstrels ... and became pious in good style." Parkdale gave as good as it got from the "dirty, tax ridden, dimly lit, burglar ridden squash pit" next door.

The slanging match swelled into true civic conflict. Its decisive battle would come where Town and City faced off across their contested frontier: that spot where railway tracks slashed Queen Street.

|

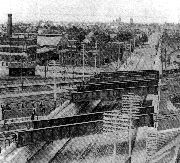

Parkdale's Waterloo

Inscription, above, marking the Queen St Subway of 1897, shown here in an 1898 view looking west over Parkdale -- replacing an 1885 underpass locally known as "the dreadful hole." |

Approaching Parkdale from the east, on Queen, one is greeted not by a welcome sign but a looming expanse of grim steel, labelled "CN." For those heading in from downtown, it marks where the neighbourhood begins. It also marks where the Town of Parkdale met its end.

The place was, in fact, beset by doubt even before it became a town. The City of Toronto, avidly expansionist, had been irked at Parkdale becoming an independent village in 1879: it stood in the way of civic expansion to High Park, donated to the City by John Howard six years before. Parkdale had bought 240 feet of lakefront from Howard in 1881: on it they built their own waterworks.

They'd hoped to get his land to the north too, known as Sunnyside for his villa once there, but in 1886 their new town was kept east of Roncesvalles -- but for that strip. And thankfully: Toronto's tap water, Parkdalers said, tasted "of purgatory and death." Another good reason to shun scandalous Hogtown.

Not all floral suburbanites were so wary. In 1884, "at the request of a large number of the leading ratepayers of Parkdale," talks were opened with the City -- on annexation. In December of that year villagers voted in favour -- only to be rebuffed. Toronto had taken a close look at the books.

Progress had outpaced Economy: the Village had at last paved a few streets (with cedar blocks), laid sewers, rented a fire hall and paid a few constables. It was said that the treasurer was "addicted to drink." Much as the City wanted Parkdale, it refused to annex its debt (and had scandal enough of its own).

Most of that debt had been incurred in 1883, on contracts for the first subway under the tracks crossing Queen. Most of it lay on City land; the City had agreed to pay its share, the rail companies too. Toronto backed out; the railways would be slow to pay, short of legal action. Parkdale pressed on and got its underpass: "a dreadful hole" of "mud and slush." And more debt.

Toronto had annexed Yorkville in 1883, Riverdale and Brockton in 1884, by 1887 The Annex. In 1888 it swallowed up Sunnyside. Roncesvalles became a boundary: the City had Parkdale surrounded. But its appetite had apparently put it in a more charitable mood.

The people of Parkdale, yet again, debated their fate. Annexationists raised local colours (if amended): "Economy, Union, and Progress." It was time, they said, for "greater efficiency" and "less squabbling." On October 27, 1888 they (including absentee landlords carted in from downtown) cast their votes: 467 Yes; 339 No.

The forces of "Home Rule for Parkdale," claiming voter fraud, launched a suit. They lost the case. And the Town of Parkdale. On March 23, 1889, it became just one more ward of the City of Toronto.

In 1897 the City rebuilt the "dreadful hole." By 1923 the four railroads roaring over Queen had become one, nationalized as the CNR. It has since been sold off in the name of privatized "efficiency." Parkdale's welcome sign is now a corporate logo, turning its grim backside to the once proud town.

|

Rails, road, highway

Parkdale's lake front, looking east from the foot bridge leading from Queen & Roncesvalles. The first track was laid by the Great Western in 1855, Lake Shore Boulevard, far right below, dates from 1919; the Gardiner Expressway, roaring between, arrived in 1955. Once here: streets lined with lakeside retreats. |

Railways also shaped Parkdale on another front: the lakefront. Its relation to the water would grow ever more remote. Getting down to the shore had never been easy. That military map of 1863 notes "rock banks v. steep, from 10' - 25' high" along Humber Bay's eastern edge; the one of 1833 shows the "Road to Niagara by the beach" beyond Brock's Land heading straight to a "sudden sharp descent" just past the spot where Queen now meets Roncesvalles.

The Great Western's 1855 line to Hamilton forced their engines to face "very steep grades" up and down from the rolling highlands rising north of the lake. Beginning in 1910 they carved the tracks into a deep ditch; South Parkdale Station, remaining aloft, was abandoned.

Few streets crossed the tracks, their run fenced on both sides. Residents took to scaling the fences, skirting traffic between, then scrambling down 30 feet of cliff to get to the narrow beach, most of its stretch in private hands. For a public if much longer wander to the water, they had to head east of Dufferin: there, in 1878, the Toronto Industrial Exhibition had moved to the lake shore, becoming the CNE. Or they went west, to Sunnyside; its beach, long popular, was packed after its big amusement park opened in 1922.

Between water and rails sat homes on streets named Dominion, Victoria, Cliff Road. A 1916 map shows more, and a darker line: a proposed "Boulevard Drive" meant to span the entire waterfront, bridged at Bathurst and beyond to take in the Toronto Islands. Begun in 1919 as the "Marginal Boulevard Driveway," it was later lent Queen's former and more picturesque moniker.

What we know as Lake Shore Boulevard remains quite scenic (if with views of, not from, the Islands) -- unlike the barrier that would later flank it. The Gardiner Expressway was begun in 1955, picking up where the Queen Elizabeth Way had left off when dedicated on a royal visit in 1939 -- not by the reigning monarch but her Mum, with husband George VI. Running to Niagara, it was first known simply as "Middle Road." But, even then, it was clearly designed for pleasure.

The Gardiner sacrificed aesthetics -- and much else -- to speed. It was the dream of Frederick G Gardiner, first master of the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, a 1953 alliance of Toronto and 12 surrounding burgs, in time coalescing to six (the City getting the villages of Swansea and Forest Hill in 1967). It was the era of automania, Gardiner its prophet, the expressway his massive monument.

|

Pedestrian way

Queen's west end, seen from Lake Shore Boulevard, looking under the foot bridge -- leading over it, & tracks, & expressway -- from the crossroad at Roncesvalles. |

"The history of Toronto's waterfront" --as Toronto Life said in a recent issue filled with ideas "reimagining" it -- "is a history of missed opportunity." The 19th century city's hopes of a lakeside "esplanade" remains only in name: it went to railways, then highways. Downtown, the Gardiner stands on massive stilts, grim and crumbling. There's talk, if so far just talk (being cheap), of burying it.

Across Parkdale the Gardiner already runs in a ditch widened, since first dug by the Great Western, all the way to the water. Standing on King Street one is still at the edge of a cliff, looking over rails and rushing traffic to the vast expanse of Lake Ontario -- too far beyond. Between Dufferin and Roncesvalles there is only one route, Jameson Avenue, that can take you there by car.

Where King, Queen, and Roncesvalles meet, there's a pedestrian bridge. At its south foot is a relic of better times, built for "Dean's Sunnyside Pleasure Boats," famous for the "Sunnyside Torpedo Canoe." But a dance hall there, opened in 1922 along with the big beach amusement park, would make it much more famous: in the era of Big Band Swing, nearly every hot act on both sides of the lake played the Palais Royale.

In 1955 Sunnyside was run over by the Gardiner Expressway, sparing just its bathing pavilion -- and the Palais. People still dance there. And stroll, maybe even swing, to the rhythms of one very big lake.

So near; so far: The Palais Royale, backed by Lake Ontario at Parkdale's west end. Below: the view from King St at the bottom of Wilson Park Rd: fence, railside wires, expressway lampposts -- & the lake.