FATE SHAPING HURDLES

FATE SHAPING HURDLES

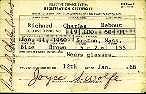

Bookets bearing my scores for the 1966 NMSQT; 1967 SAT -- anxiety's acronyms

|

An American Education

Politics

Partisan; & the politics of education

Coming out of Ayer High (widely renowned), I could still seem destined for ivy halls. Maybe in time even grad school. Everyone said so. And surely there were scholarships....

I still have the 1966-67 Handbook for Merit Program participants of the National Merit Scholarship Program. A certificate inside says I took the its Qualifying Test in 1966, awarded a "Letter of Commendation." A chart I filled out, based on my results, shows I scored in the top 10 percent. As I had (or better) in the SAT, the PSAT before.

I also still have a certificate saying I achieved "an outstanding class score on the 31st Annual Time [magazine] Current Affairs Test" in 1967. And one issued by the Massachusetts Civil Defense Adult Education Program, October 14, 1966, proving I "attended a twelve hour course in Personal and Family Survival." I recall neither. And, but for that National Merit booklet, I forget taking that scholarship test.

(As I don't forget those kids at Ayer High; I did check names in my yearbook -- but I didn't need that to recall them. Even kids Class of '68, '69, '70: hundreds of small shots with just surname and initial; I still knew most first names.)

I don't know what happened -- but that my family was not of the sort intimate with the intricacies of how such things happen.

Mind you, I did get a scholarship. On graduation night, June 14, 1967, I was called to the stage to receive The Jonathan F Moore Memorial Scholarship, in the amount of $100. I may have been the only one there to think it nepotism -- if not, had the amount been widely known, a bit niggling.

NOT JONATHAN

NOT JONATHAN

Victor (George Junior indeed -- here in 10th grade, from my yearbook): Childhood friend, third son of the Moores & third to die, all classically: "Dead Man's Curve"; Vietnam; AIDS

|

STUD(ENT COUNCIL) MUFFINS

STUD(ENT COUNCIL) MUFFINS

Teddy & Tommy: behind me & Jackie Jurga (her mother my 6th grade teacher). Brother Bill, if graduating Bennington High, saw Ted last year at a 30th reunion: Class of '70, AHS; Ayer still home in spirit

|

TRACK TUTORIAL

TRACK TUTORIAL

Ayer Depot (again arted up by Bill Rowe): much as I knew it I think, if no longer; life again shaped by -- here, on -- the Boston & Maine

|

His quiet brother Douglas would last be home in 1968, in a box shipped from Vietnam. George would have a heart attack, at home (a new one on a Groton hill, built for $100,000 -- the Maxants at last outscored). He'd not be found for days, Zelda away on a trip.

Skinny, quirky Victor (a little George, in fact I think George Victor Moore, Jr; we'd been friends) had got the house on Taft. On Main Street he'd run a card shop. He once shared a house in Harvard with a man I knew from Ottawa -- Bob Read, high in the ranks at Digital, its head office in Maynard, next door. Victor would die, some years later (Bob too, if later still), of AIDS.

Everyone of course found themselves reminded, and said so, of the Kennedys.

Zelda, my mother told me, had said Victor's death was the hardest, never stating its cause. In The Public Spirit she asked for donations, in lieu of flowers or other charities, to the Ayer Library. I don't know how Victor might have felt about that, but I appreciated it. It was the one truly beautiful public space in that town. One I'd known well.

Zelda survives, lately renovating a late 19th century block on Main Street, helping bring Ayer a sense of history that it had, in its long and now gone heyday of easy Army money, not much bothered with.

For my 50th birthday Aunt Alice sent an afghan, huge, woven into it some local landmarks: the Town Hall centre (bannered "Ayer, Massachusetts; Incorporated 1871"); others familiar to me: the library right above the banner; the post office, fire hall, Pleasant Street School; the long, arcade fronted Page Block on Main Street, now Page Moore.

The police station is new to me (if still Federal Style); the rail depot too. Across the bottom runs a steam locomotive, beneath it "B&M Railroad." Smaller, at the very bottom: "Designed exclusively by American Legion Post 139."

Calvin lives too. Butch little devil of the family I recall him, friend of my brother Bill, hanging out with taciturn Teddy Harrington and straw blond Tommy Jodka, stud muffins both. Tommy's father owned the local record store, once baffled at my ordering in, age 13, the boxed set of Brahms' Ein Deutsches Requiem.

Once, set to perform parts of it at a school assembly just weeks after November 22, 1963, Jack Carton gave us a look, the room unsettled, then silently mouthed: "No." Remarkable restraint for Jack. But he knew we'd get it. He had taught us reverence.

Calvin Moore now runs a much expanded Moore Lumber and Hardware, that old mill canal long filled in.

And I imagine -- even hope -- that he's grooming an heir.

That $100 bequest in memory of Jonathan Moore, a note enclosed tells me, was "mailed directly to the Bursar of Boston State College to be applied to your account."

Boston State was one of many Massachusetts schools born state teachers' colleges. There, $100 did go some way: it covered half a year's tuition. I covered the rest, and my expenses, working summer jobs. I had at least done better than Fitchburg State, though BSC ("Bull Shit College" we called it) wasn't a patch even on Ayer High. There I'd worked hard to be fifth in my class; at State I was, always, a lazy first.

But it gave me Boston, and the trip there. Early on with Bobby Lawton, a year ahead of me at Ayer High, crophead handsome son of Dr Lawton, DDS, and very quiet. Well, I was a paying passenger, picked up promptly at 7 am.

Later, the train; I seem to owe much life experience to the Boston and Maine. It was a run of just 35 miles -- announced outbound from North Station, 5:13 pm, I'll never forget: "Waltham, Roberts [Brandeis there], Kendal Green, Lincoln, Concord, West Concord, South Acton, West Acton, Littleton, and [passing 9 Birch Street] Ayer."

On that train a set of facing seats, sometimes the one beside too, became a world all its own. Sally was there; Sarah Aldrich I'd known her, a high school girl doing ironing for my mother when I was about 12.

She was cheery, gamin, almost child like if never childish; very smart. Sometimes we drove, in her orange Beetle. For Christmas 1968 she gave me two jars: peanut butter, and jelly. I later gave her a painting. I was painting then, polemically -- hence badly. I'd done a vicious white gremlin under a powder blue helmet: a mad Chicago cop from the 1968 riots at that year's Democratic convention.

Another was inspired by Rowan & Martin's Laugh In. Not its famous "Sock it to me!" -- but "Be that as it may...." words turned to a bit of cheap cubism in grim Capricornian purples and greys. Sally loved it (she'd come to 66 Pearl on Monday nights for Laugh In), asking me to do her the same, in Leo: orange, yellow, black, "Sally green." I did.

I'd later see Sally in Montreal, there visiting Charlie Brown, of those Harvard Browns. Charlie was a genuine draft dodger. I, as it turned out, would be one only in spirit.

There were others there, college kids, business types who, for part of the route, were part of our crew. There was even a poet: L E Sissman who worked, Wallace Stevens like, in some corporate office; in that 1969 chapter of my memoir you'll find a few lines from his "Peace Comes to Still River, Mass." Sally knew about poets, but L E was usually in the other car.

Always with us was Harry Imoto, in Navy uniform, office variety, fierce looking but not really. He liked uncapping beer bottles with his teeth. Near the end of the run, Ayer its last stop (then; it goes to Fitchburg now), our Budd car (of two) near deserted, a genial conductor would sit down with us and break out the booze.

My very first memory of feeling even tipsy (a Very Good Boy indeed) came with a step off that train -- weightless. I tottered home steadily enough.

YES, REPUBLICAN

YES, REPUBLICAN

Well, I did find excuses

|

Bart (Hobart Harrington; descended he said of Grover) Cleveland had left the Navy in 1965 if, to good effect, keeping those bells; leaving too his role in the early stages of US intervention in Vietnam. He had been there, liked to tell us of eating dog; he'd quit in disgust at things worse.

Bart was a presence (I was smitten, if realizing only later), intensely political. We ended up in local meetings of a group called Citizens for Participation Politics, and participating in a political campaign. For (are you ready?) a Republican.

Well, a liberal one, Mayor John Lindsay of New York his model. Mike Peabody hoped to win nomination to battle a dinosaur Democrat for the Massachusetts Third District's US Congress seat. His liberal Republicanism was old family patrician, steeped in noblesse oblige; an ancestor had founded Groton School. (Bart liked to say it was all penance for the Slave Trade.) It was even ecumenical: his brother Malcolm "Chubb" Peabody, a Democrat, had been governor.

His mother was a Parkman, descendant (maybe daughter) of historian Francis Parkman. A grand if unassuming lady, she had once called her son the governor from the South: "Chubb, I'm in jail." She'd been arrested on a Freedom Ride.

At the campaign office in Newton Corner, Mrs Peabody stuffed envelopes with the rest of us, living on pizza and root beer from Pelligrini's next door -- a political cliché I know; but it was true. I wrote a campaign ad for The Public Spirit -- "Change: The need is now." Talk about clichés.

I canvassed around Ayer with Bart, with him and wife Jean went to polite parties in the tonier parts of (generally tony) Concord, Lincoln, Weston. Of one, hosted by the sister of the famously radical Reverend William Sloan Coffin, I wrote later: "There was little slave labor present. Just money. The house was beautiful, from the indoor pool to the Picasso in the living room."

PARTYING REPUBLICAN

PARTYING REPUBLICAN

Jane Lawson (who sent me this shot), Gridley Clapp, I & Jean Cleveland, attentive at the Rowe's, Pam Peabody's parents. Fun, eh?

|

Most were less ostentatious, old money New England famously reserved, if far more than local gentry. They were among the nation's elite -- if rooted in ancestral turf. There's a story, perhaps apocryphal, of a Brahmin grande dame who, offered kudos on her son's political success, said: "Oh, well, that's just national. It's not Boston."

The Brahmins had long lost Boston, politically if not financially, to descendants of the Irish their ancestors had disdained to employ. But in those towns around, nearly as old and well preserved even as they became bedroom suburbs, old money and its manners still had some sway. I could like these people -- even if I could never quite say "toe mah toe."

Among my fellow campaigners at Newton Corner were kids of good families, bright destinies. The Crosby's: Becky and big brother Steve, usefully studly: he'd later ponder a seat in the Massachusetts House (or, as more properly called, The Great and General Court of the Commonwealth). I don't know if he ran.

There was Gridley Clapp. Roger, a bit older; I forget his last name now, but it must have related to what we often called him: Nushkie. In fact, "The Nushkie."

Roger might have been the model (if made smaller, darker, and given a Boston accent) for Bill Clinton's James Carville, a brilliant if zany backroom boy. "He influences policies at the senatorial level," I once wrote of him, "yet can run around being a nut at the same time. It's great."

Jane Lawson's family had a farm in Lincoln, or maybe Lexington, marked by one of those classic roadside stands where Route 2 dipped back up from its westward run down Belmont Hill (not a big road then; a superhighway now).

"The old apple and pumpkin season is in full swing," she'd later write me, "and I'm sick to death of it. If I see one more crumbly taffy apple I'm going to turn into one." One Sunday she and her mother made 1,080 "of the damn things." Later: Christmas trees. Jane was one of the few with whom I kept in touch, even her not for long.

DEMOCRATIC PARTYING

DEMOCRATIC PARTYING

More at home with Seeger, Albee, Lenny & Gene

|

Steve went with him, Becky too, as a Congressional intern (a post I'd ponder, if past that year's application deadline). Mike and wife Pam sent Christmas cards for some years, their cute boys Payson and Carter bigger each time.

I'd get a letter from Steve there, forwarded by Jane with a note: "the above may be torn, mutilated, stepped on, used as kindling or desecrated in any way, shape, or form." It was a computer card, for US Social Security, notice of the $130 I'd been paid by the Peabody campaign. I'd forgotten.

But by then I was no longer in the USA -- if still with another card I was not to bend, fold, spindle or mutilate: my draft card. I had torn it in half and posted in on the wall of my first Toronto abode.

Not, I must admit, before having sunk to depths lower: the February 1969 Lincoln Day Dinner, regular Republican rubber chicken fête. Well, it was a sort of reunion, so I did have an excuse.

I went from Republicans to Democrats: McCarthy's Massachusetts presidential primary campaign. I didn't do much there, recalling only a confab in the Boston office over the colour of a draft brochure: "Red! Are you kidding? Green!"

I did feel a bit more politically at home, crammed into Fenway Park to see Pete Seeger, Erich Fromm, Jackie Washington, John Kenneth Galbraith, Edward Albee and Leonard Bernstein fête the good senator. Of course he lost, too.

On election night, November 1968, I was back with the old gang in a Republican HQ, again safely liberal, John Sears trying to evict the Democratic machine from the office of Suffolk County Sheriff. Many there that night had a button under the lapel, covertly flashed to the likeminded: "HHH" -- Hubert Horatio Humphrey.

But it was "Nixon's the One!" that won, a button on a famous poster, worn by a young woman: black, sly -- and very pregnant.

Margaret Hudlin, then at Newton College of the Sacred Heart (not yet anathema by marriage), wrote me on November 22: "...would you think it over, and tell me what you think of a revolution now????"

Next: College: Higher education (yeah, sure)

Go back to An American Education / Introduction

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/me/politics1.htm

February 2001 / Last revised: October 5, 2001

Rick Bébout © 2001 / rick@rbebout.com

CHEAP BRAVADO

CHEAP BRAVADO