|

MOORE LUMBERED

MOORE LUMBERED

Ayer High kids cavort in a yearbook sponsor shot: Charlotte Ammons atop; Kathy Sullivan in the cab (I hope with Dick O'Toole)

|

An American Education

Local gentry

In the land of noblesse oblige

In May 1958, I eight years old, my family got a new house. It was up northwest of downtown at the top of Pearl Street, number 66, the last number (then) before the land gave way on the north to fields.

To the west it fell down a long hill, our backyard, to a branch of the B&M, the one crossing Main Street further south. In a rail town it can be hard to tell, even literally, which side of the tracks you're on.

On the first day my father took us to see that house (my mother then 30, he 28; Debbie, Billy, Gary and now Mark, still a baby; Brian and Joanne yet to come), I sat in the car and cried, refusing to go in. It was derelict, a weathered grey two storey hulk long abandoned, a huge barn beside also falling down, on land owned by my father's employer, George Moore.

Lots of land, I assume now; his own father Levi still lived in a place of similar vintage, if bigger, about halfway down Pearl's rolling asphalt. The Moores were local gentry. They owned what was then the G V Moore Lumber Company. It had been Levi's, perhaps even his father's before him. My father had started work there as a truck driver; he had become general manager, later vice president.

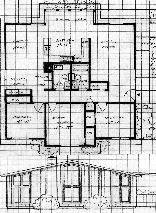

My earliest (perhaps only) professional aspirations were also born of Moore Lumber, finding there builders' calendars full of floor plans for the sort of houses then dotting developments everywhere (some locally, built by George Moore with streets named for his kids).

I was soon imitating them. Often literally: my early designs were modest, family focused; my father's occasional critiques looked for economical use of plumbing cores, standard windows from the Andersen company catalogue.

I'd get more dramatic -- concrete and glass -- if still modest: abodes for a single person, some little more than well appointed bedrooms. Bachelor pads, you might say. I never said "pad," but aspirations beyond career were apparent. From the age of three or so, I'd never had a room of my own.

I'd give up hope of a career in architecture by 11th grade, my math marks starting to slip. In the meantime I did have a trade. After school I worked at G V Moore, too. As a janitor. I liked best burning trash out back, next to a rail embankment. Just south the line bridged Mill Street, beyond was much Moore lumber, and the Williamses: one of the few local nonmilitary black families, less well off than the Wises or Hamiltons.

That bin was also reached by a bridge: the "new" office wing built across the old mill canal. It was an odd, magic space. And there, if just for a brief blaze, I was free of the scrutiny inside: my father's. I felt incompetent under his gaze, particularly with the roaring canister vacuum. Not to mention the Cokes and 5 cent candies -- Sugar Babies, Snickers, Good 'n' Plenty -- I downed as solace on janitorial rounds.

I can still hear George Moore, ever patrician, answering the phone: "Moe aah Lum bah, Jawge speakin'." His manner didn't always win complete respect from his workers or their dependents, despite noblesse oblige.

(My father hunted with Levi. He'd inherit his dog Dotty, old and famously good; she lived out back in a pen, with Jupiter. The house beagle Mitzi was too fat to hunt but loved going on family rides, often to Groton for ice cream cones; she'd look forlorn if about to be left behind. At night she'd be on one or another kid's bed.)

My mother recalls George's wife Zelda carefully instructing her how to eat lobster, my father's favourite tale even better. Showing vacation slides at a party George, coming to a shot of Zelda standing beside a sign, intoned: "And hee ah we have the entrance to the Grand Canyon."

In 1958, my father was earning about $9,000 a year. Sixty six Pearl cost him $16,000, with renovations -- supplies ready to hand and helping hands too: I recall (having relented) smashing at old plaster and lath in what would become a decent late '50 kitchen: Thermidor oven and matching countertop range, built in, stainless steel; the double sink too, so pristine it saved us kids our usual sink side chores.

Mum didn't want it scratched. At least not right away.

|

More local gentry, by the Moores' lights maybe a bit upstart -- but nothing like that scandalous Lester Berry. His gleaming new liquor store dominated Ayer's main drag; his Little Club hosting too many GIs free of Fort Devens on payday (and girls aware of the Army's pay schedule; maybe boys too, if not working: once, years later, I'd find the Little Club listed in Bob Damron's gay guide).

The Maxants weren't right at the corner of Pearl and Taft, kitty corner to us, but down a long driveway in a long low house of rusticated beige blocks, under a sweep of hip roof. Only later would I know the style as "Prairie," a Frank Lloyd Wright knock off, if in stone.

I knew then only that it was the most expensive house in town. Richard Maxant (from the Midwest, his father had bought the local Chandler Machine Company) had spent $45,000 to build it.

His wife likely had some say in the design; she did in everything, and was born a Prairie girl. All I knew of that was what I have come to know (mostly by watching that ever practical Minnesota pair who do the housebuilding show Hometime) as a certain chipper, down home brand of Midwest authoritarianism.

Harriet Maxant was the local tyrant. To us kids anyway. When we were there she'd always have some task for us. I don't think she ever mentioned the devil and idle hands; she didn't have to.

We were put to pulling weeds in the gardens (vegetable and fruit; the raspberry bushes murder); feeding penned rabbits (quite a few); helping make sugar cookies in her kitchen or cranking the churn of an ice cream tub plunked in freezing brine.

Taking us anywhere she'd order us to buckle up: the Maxant's big Buick (or maybe it was an Olds) was the only car we knew to have seatbelts -- weird to us then.

I worked one summer for her, on harder tasks: wrestling an industrial power mower fronted horizontal by a slashing brace of teeth; taking care of the horses: Shirley, a gentle old girl, and Mohawk, a stallion young and moody: he once clipped a crescent of skin off my brother Gary's forehead.

I carted hay and manure and rabbit shit; weeded, not the least casually. I came to hate every last iris lining that long driveway and recall, still, crouched there one hot afternoon fantasizing flight from harridan Harriet. An awful longing -- fed by the sound of a screen door slam on my own kitchen porch, not a hundred yards away.

Her own kids were grown. Ruth was three years older than I, blond hawk faced Frank four more. He and I sometimes worked together, cleaning up another Maxant machine shop, in the moment disused. I liked Frank. He was soon off to Cornell.

And Edith, born between them, with Down's Syndrome. To us kids, Edie seemed just one more of us. Bigger of course, but genial; she had a great, deep chuckle. I still remember her birthday, as she always did and would tell us: "Augus kwewlf."

Edie wasn't the only kid we knew with Down's. There was a Maxant cousin, Kammie I think, in Harvard just south; just down Pearl Street Althea Peroni.

|

HIGH SCHOOL PUNDIT

My column in The Public Spirit ran just a few months, in 1967. Looking back at clippings I still have, I was surprised to find them not embarrassing (or not much). So, for the flavour of the times, I've put them online. See Punditry: At seventeen.

|

HATTIE

HATTIE

Or so she'd been; here taking songs solo across Germany. Photo from The Public Spirit, courtesy of Ruth Maxant Schultz

|

Or that the big sun room of that rambling house had a ping pong table, cupboards full of puzzles and games, and lots of kids -- Bebouts, Cornelliers, Rakips, Blacks (Schwartzes originally; dad had found Black more smalltown lawyerly, though the Sauls lived nearby too). Neighbourhood kids. None born Harriet's, but Harriet's charges nonetheless.

Much later, that reflection came: November 1999. My brother Gary, back east on a visit from L.A., had picked up and sent me her obituary in the local paper, The Public Spirit. (I'd briefly done a column for it, called "Student Viewpoint.") "Ayer's pioneer woman, Harriet Maxant," that 1999 headline read across nearly a full page, "travelled the world." I'd never known.

Born Hattie Elizabeth Henn, 1908, in Iowa if daughter to Oklahoma Territory homesteaders (hence "pioneer" -- a bit of a stretch, at least literally; but hey, that's journalism). They'd kept the land, sitting, as it turned out, on pools of petroleum.

She went from one room schools to the Iowa State College of Agricultural and Mechanical Arts, getting her Bachelor's degree in 1929. Later it was business school ("one of the very first females to become a typist," the contraption first thought "best manipulated by a male"); later still she taught at one.

She changed her name to Harriet: "People were simply not going to hire a Hattie."

She studied at the Chicago Theological Seminary; taught kids in the South. Took voice lessons in Munich, touring Germany and later the US, solo, in folk costume. "She came to dislike intensely the self important strut of the black shirts doing the goose step and other strong armed tactics of the Fascists. Wisely, she left before she might have been trapped there."

As Harriet Maxant she worked with the Massachusetts Association of Women's Clubs, the Nashua River Watershed Association; with other parents of children with Down's Syndrome. She sold the World Book Encyclopedia (even when I knew her).

Her house (long after) hosted Harvard guest speakers, a Russian, a Pole; and kids sent "for an experience in a more rural New England" by the Fresh Air Fund of New York. "Ungrammatical language that she heard spoken always drew from her a gentle correction." That I knew. I wish I'd known the rest.

Maybe in a way, even in resistance, I did. Ruth Maxant, quoted in that obituary, said that, for her mother, "teaching never ended."

Next: School: Primary, secondary; public -- & exemplary

Go back to An American Education / Introduction

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/me/gentry.htm

February 2001 / Last revised: October 5, 2001

Rick Bébout © 2001 / rick@rbebout.com

DERELICT RECLAIMED

DERELICT RECLAIMED

CAREER DREAMS

CAREER DREAMS

MAXANTS (& ABODE)

MAXANTS (& ABODE)

"CHANDLER, AYER, MASS"

"CHANDLER, AYER, MASS"