|

Promiscuous Affections A Life in The Bar, 1969-2000

1987-1991:

|

"No cute boys & no dark corners" -- no surprise party, thank god. From Michael Lynch for my 40th: Magritte, with a message. |

1990

January through March

- Monday, January 8, 1990, to Jane:

Gerald is mildly miffed with me. He and Michael Lynch had called Paul Pearce to see what to do about my 40th birthday and Paul told them, as he knew, that I wanted them to do nothing much at all.

Paul did call me though, put on the spot. I said he should simply ask Gerald and Michael to a regular Saturday dinner with himself, David and me -- buying off the instigators with a nice gathering, just the five of us. (As it turns out Michael isn't free on Saturday. David called this morning and suggested Kevin Orr, who is.)

Gerald hinted that what I wanted wasn't really the point, joking that I should be willing to indulge my friends at least once every 40 years. I said we'd do it when I turn 80.

Gerald saw some selfishness in this, an "exercise of my powers" as he put it. He was right. I knew these days what I wanted, what not, and had little trouble saying so. That power came in part from a sense of shortened life, not that it felt short from day to day.

"Still," as I told Jane, "I do have a stock of moral absolution I can trade on from time to time, though it's cost me almost nothing so far. I don't use it very often." Gerald and Michael forgave me this rare use of it, Michael writing:

- Relax. I'm not throwing you a surprise party. I can't even come to the huge surprise ball and banquet Paul and David are concocting (with you in the perpetual spotlight and no cute boys and no dark corners). Relax. Have a glorious 41st, or whatever it is. I get so confused when it comes to younger men.

***

At dinner with Paul and David six months before, we had talked about blindness -- not David's but Gram Campbell's. Alan Miller had been there but not Gram, in hospital after surgery for a detached retina. He had CMV in the other eye, soon in both.

David urged Alan on and Gram through him. Look how well he himself had done, getting around on his own, working on his talking computer, even learning Braille now.

But Gram's passion, graphic design, could not be made to speak, or to communicate its message by touch. He withdrew, wanting to see no one but Alan. Later, back in hospital, he made that plain: he didn't want visitors, didn't want friends to see him as he was by then, no longer beautiful when he had always been so beautiful.

By now he was in hospital again, completely blind and nearly comatose. On Wednesday, January 17 he died there, with him Alan, Ed Jackson, and his parents in from Montreal.

Gram's parents were very old, he their only child. He had never told them he was gay until he had to, dying of AIDS. They were distraught, ungiving even to each other. In Gram's obituary they noted an ancestor from 1776, but not Alan.

At the funeral they sat up front, Mrs Campbell stately in a fur wrap looking, as I told Jane, "like aging Westmount waiting through the appropriate finalities to collect the remains for burial at Mount Royal." Speakers addressed their grief; none mentioned Alan.

- Friday, January 19, 1990, to Jane:

It was in the chapel at the Rosar Morrison Funeral Home. There is something relentlessly tacky about funeral homes, the staff fake solemn, the decor pseudo religious, the organ moaning out tunes utterly devoid of content but full of "appropriate" tremulosity. They belong in shopping malls.

Paul and David came in and sat behind me, Gerald beside me, and I turned to Paul and said: "As my executor it's your job to make sure I never end up in a place like this." He laughed. "How could you even imagine I'd let such a thing happen!" Yet it had happened to Gram.

It had happened to Gram, in part, because Gram had let it, his endless niceness sparing his parents anything of his true life but for this one, last, awful moment, sitting in a room full of people who couldn't wait to be rid of them.

Looking at the back of their heads I found myself thinking: I hope that someday you will be deeply ashamed of this moment.

***

"We stand together!" Gram's work, including logo for the Toronto PWA Foundation, & their archer taking aim. |

Later, we held our own memorial for Gram, a big room full of his work, up on the walls and spread out on a dozen tables.

His journals were there, pages and pages covered in notes and images clipped from magazines. At April 1, 1986 it said "AIDS diagnosis." A page in 1988 had a label from his Acyclovir and a calculation of its cost, more than $4,000 a year.

The handwriting was a designer's neat script; the images anything that might have caught his designer's eye. It was so obvious Gram could not have cared to live without sight.

His journal for 1990 was left for us to finish. People stuck in notes, poems, pictures. My contribution had come from Gram, a card he'd made with my name in a cut out over a silhouette of a strong figure flexing his biceps. "Genuine voodoo T cell booster," it read, "Millions of satisfied customers."

His parents saw none of that. Only years later did I wish they had. In late 1998 both would die, within hours of each other. They had not spoken to Alan since Gram's funeral but he was duly notified and had to be: they had named him their executor.

In their papers Alan discovered that Gram's father had been a well known advertising designer, a pioneer of modernism from the 1930s. Perhaps they had felt shame after all.

Or perhaps not: Alan would tell me that he found nothing in those papers about Gram after his death, but for one letter written by his father to a friend. It reported that Gram had died of leukemia.

***

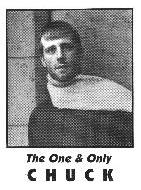

"Harmless bombast?" More his "tribute to human individuality." Cover of Chuck Grochmal's memorial program. |

A month later there was another memorial, for Chuck Grochmal. He had been at Casey House for the last few weeks and even from there he'd kept on writing for Xtra. His last column appeared on January 24, 1990. He died on February 3.

Chuck's memorial was based on Gram's, a big space full of his things, lots of photos, looseleaf binders packed with his columns, a VCR showing clips of him on the news. The small program had a picture of him on the front, handsome but looking a man who might get difficult. At times he had.

Underneath was: "The One & Only Chuck" -- as he'd sometimes called himself. Ken Popert, writing his full page obituary in Xtra, said of that: "At first I understood this as harmless bombast; later I realized that this was Chuck's tribute to human individuality. Too many activists tend the lawn but trample the blade; Chuck prized every life."

Ken was one of the speakers at the memorial, as I told Jane,

- veteran of many editorial fights with Chuck, Ken the old movement hack, ex Communist, brittle calculator, notorious cold fish -- all him, but not all of him. This death hit him hard, making him sad at the loss, angry at the waste of it all. He had a hard time speaking.

I had last seen Chuck sitting in that damned chairlift at the bottom of those damned stairs at 464 Yonge Street, waiting for a cab and not happily. He looked cranky, forlorn, and old.

Not a few people at the AIDS Committee could look like that. The wonder was that so many did not.

***

But his presence would become a blessing: one of the gods' glorious fools, on Earth just to make us happy he's here glowing among us.

A few weeks after last seeing Chuck, I was sitting in the smoking room at ACT when in came a handsome young man, six foot five and not thin.

We talked, his smile a wonder. We were trained not to interrogate so I couldn't be sure why he was there. I found out later, running into him at Boots. I told Barry about him.

- We talked and talked. He's a childcare worker, teaching with the Catholic school board, loves the kids he works with. The first he knew he had HIV was only a month ago, when what he thought was the flu turned out to be PCP.

He doesn't have much context for this, still a little closety, very much a Catholic. But so beautiful, with a core of goodness and strength. So I talked about myself, about AZT and Pentamidine, which he's due to start. What I wanted to say was simple: baby, you're going to get through this and be OK. (For a while, anyway.) He said he'd be back at the office and we'd talk again.

And we did, today. He'd got his T cell count. It was 20. For a minute I thought his doctor was using a different scale and that meant 200. But no -- 20. And I just thought: Damn. Damn!

I cope with so much, Barr, and you know what? Mostly it feels easy. But then suddenly in the middle of an ordinary day, this thing I've managed to make ordinary in my life, AIDS, becomes terrible again. This beautiful man, confused and vulnerable and trying to be so strong, and between us this monster telling me (because I know it better than he does): I'm going to take this man away. I'm going to kill him, probably soon, and there's nothing you can do about it.

I'm not usually sad in all this. I've felt incredibly lucky at what I'm still able to do, glad to be able to do, and happy doing it. You know that. But for a couple of hours after that talk with him today I felt like I'd just been slugged.

He was 27, his name Mike Robért. Soon his sudden appearance in my life would feel not an assault but a blessing. His radiance, his manic energy, his very presence -- they were surely a gift of the gods. He could almost make me believe in gods (if not God).

Mike was one of their glorious fools, sent to Earth simply to make everyone happy he's here, glowing, among us.

***

On December 24, 1989 Barry had called me, 10:30 in the morning here but a half hour into Christmas in Tokyo. He was fine, happy, at home in bed with a glass of wine, a Japanese boy asleep by his side.

This was Ryoji. He had told me about him before and I liked what I'd heard: smart, attractive and, soon off to school in Osaka, with no illusions even as he eagerly lay face down and bum up on Barry's futon.

I reminded Barr that I'd always liked it face up -- so I could see his face, his chest, his long torso all the way down to what I could feel but not see, him deep inside me. I hadn't seen that in more than two years and had no idea if I'd see it again. But now I didn't hesitate to tell him how much I wanted to.

At 7 pm on Thursday, March 8 he called again, from Chicago. This was no surprise: I'd arranged the tickets for his flight(s) back. He'd been due in at 11:09 pm but could get out earlier, so now it was to be 8:05. I rushed eagerly to Pearson International -- where the arrivals board listed that earlier flight cancelled. Now it would be 12:09 am. Then 12:25. Then 1:22.

Then there he was, three big bags over his shoulders. It had been 23 hours from Tokyo. Back at my place we stayed up 'til five.

***

|

The Rock

|

Ode to Newfoundland

While writing this chapter I was also reading about Newfoundland, Wayne Johnston's The Colony of Unrequited Dreams (Knopf Canada, 1998). It's full of tales. So here are a few.

When Barry & I landed in Port aux Basque we were still in Canada -- but truly in another country, its culture distinct as Quebec's. The language is English, but listen around any outport & you'll likely be baffled, your ear suggesting you're in Cornwall, or Ireland. That's where these people's ancestors came from, dialects preserved by long isolation.

John Cabot discovered this "New Found Land" in 1497. Fishermen followed & soon the first British "planters" -- if tentatively: it was a brutal land, especially in winter. By the 1670s Charles II, convinced the place was uninhabitable, decreed that its few settlers "be not molested but lefte to encounter whatever fate or variety of fates as may please Almightye God."

Fate decreed this a poor if proud colony, by 1855 self governing. When four mainland colonies formed the Dominion of Canada in 1867 Newfoundland stood aside, reiterating that stand in an 1869 referendum.

In 1933, bankrupt, it reverted to direct British rule, its overlords wondering what sin could warrant being shipped off to run such a place. Despite such disdain many Newfoundlanders still sang a long famous tune: "Our faces towards Britain, our backs to the gulf; Come near at your peril, Canadian wolf."

The wolf was at the door again by 1948, met by more referenda. The first was inconclusive; the second offered two choices: adoption by Canada (& its fledgling welfare state); or return to sisterhood as the Dominion of Newfoundland, nominally independent if still depending on British largesse. (Continued direct rule from Britain had been rejected in the first vote -- to the great relief of the British).

Canada won, if by a vote so close that to this day some say it was rigged. At midnight, March 31, 1949 (chosen to avoid April Fool's Day), Newfoundland became the "Old Lost Land," no longer a country but Canada's 10th, so far last -- & still poorest -- province.

A character in Johnston's novel writes in 1959:

"We have joined a nation that we do not know, a nation that does not know us. The river of what might have been still runs & there will never come a time when we do not hear it."

To many even now, "Canada" means "The Mainland," not Newfoundland. Anyone not from Newfoundland is "From Away."

Like any colonial society it was obsessed with class, if so poor that even modest signs of privilege were jealously guarded. "The quality" & "the scruff" were old local terms. Still often heard are two others: "townies" from St John's & "baymen," from "around the bay" -- that is any place else, many in outports long accessible only by water.

For all its history until a few years ago, when the cod stocks were decimated by huge commercial fleets, Newfoundland's economy was built on fish. "The quality" claimed to hate fish -- as gentry so often sneer at the mess & stink on which they prosper.

Outside St John's & inside much of it the culture was one of poverty -- hence a culture rich in forbearance & dry wit. On our visit Barry took me to Torbay, where the Pope had blessed the fleet, fishing boats out in the bay anchored in the form of a cross. A man in the lead boat was given the honour of calling out, "We tank you Holy Fadder!" Six months later he drowned.

It's a story relished all over The Rock, echoing a tale of the founder of St John's, related by that same character in Johnston's novel:

"In 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert sets out in search of a passage to the Orient but settles for claiming Newfoundland in the name of Queen Elizabeth I. Upon leaving for England, he takes with him a piece of turf & a small twig, symbols of ownership which, unlike him, remain afloat when his ship sinks in the mid Atlantic."

The culture was also dominated by religion. The Basilica of St John the Baptist rose high on a hill over his namesake city. Its bells had rung home the sealing fleet -- in celebration of those who survived. Cultures living off the sea know death very well.

A third of Newfoundlanders were Catholic. Until the late 1990s publicly funded schools were denominational; it's a rare comic from The Rock who doesn't have a routine about nuns. Most of "the quality" were Church of England; many of the rest, if not Catholic, were Pentecostal -- the church of the poor.

Barry had been raised a bayman, & Pentecostal. He'd toured the province in a church choir, his high voice marking him the town sissy. I once saw a picture of him, around 20 I guessed, his eyes & mouth gentle, his hair just long enough to softly frame his face. I said I liked the look. "Yeah," Barr said, "but he was nobody."

Barry had been one of many from all over Atlantic Canada who ended up "Goin' Down the Road" to Toronto, for work. That phrase titled a 1971 film, a Canadian classic. Heading into The Big Smoke, the skyline in view, its boys -- from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia's own Newfoundland -- yell out: "Toronto, here we come! Lock up you daughters!"

A friend of Barry's, speaking of another due in town, once said, "Toronto's not ready for her!" Toronto barely noticed. For such kids the city offered what cities often do to people from small, tight knit communities: a shit job, a ratty flat, a life of anomie.

When they found each other -- often as soon as they could -- they tended to stick together. Some did try to blend in, curbing the accent, polishing down the rough edges.

Barry always hated that. Once, he and that friend in a Toronto bar, someone asked where they were from. "Down East," she said.

"Well, she may be from Down East," Barr said, "but I'm from Newfoundland."

Cabot Tower, Signal Hill St John's, Newfoundland. Photo: Toronto Reference Library. |

Of our trip together Barry said: "It's a fantasy. It's not real. Not really."

He was right. Reality was Barry not in Toronto, not even St John's -- but in Tokyo or trekking beyond. There could still be letters, but we might never see each other again.

Those bags were full of gifts. Festive envelopes filled with yen for his nephews; Australian opals bought in Hong Kong for a sister; for a friend in St John's a robe, one for me too.

Also for me: temple prayer sticks in a small drawstring bag; a two litre cask of Suntory beer (to have as always with pizza and talk) -- and a daruma: a fierce faced creature in papier maché, shaped like an egg but twice as big, based on the legend of a Buddhist monk who'd sat meditating so long his legs had shrivelled up.

Its eyes were white. You were supposed to paint in one pupil to let it see good and then, on one of Japan's many festival days, paint in the other -- to see bad -- but then immediately smash it to set the good free and send it flying to heaven.

More amazing than all of that to me was Barry himself. As I later wrote to Jane: "Through all this gift giving and receiving and unwrapping he talked and talked Japan and himself in Japan. I sat there tongue tied at how much of this man there is now, so big and strong and himself."

Finally we fell into bed, suddenly avid -- yes! -- but both too tired for much that night. There would be more nights.

Barry had a few errands in Toronto: a doctor's appointment; a dentist -- and rescuing his jeep from Randy, who'd been happily tooling around in it. We had dinner with Paul, David, and Gerald. At my place we drank the Suntory, had pizza, talked and talked. On Sunday night, for the first time since January 1988, I tasted his cum again.

We were both eager to escape Toronto, the ghetto, Randy just down the street and ACT a few blocks away. We had known each other here apart from all that, had never shared each other with it and didn't want to now.

The next day, at 12:45 pm, we got in the jeep and drove off.

***

We got to Montreal just in time for rush hour, picking up the Trans Canada Highway where it swoops down from Ottawa and points west. We would be on it for the rest of our trip.

We didn't stop until Quebec City. A quick tour told us we'd not get a room in the old town. We found a motel in suburban St Foy. The next day we set out for New Brunswick, at Edmundston passing a small bridge over a small river, the Saint John. Just across it was Madawaska, Maine, USA.

Farther along I scanned hills to the south for a clear cut swath that I knew marked where the border, not firmly set here until 1820, left the river and headed due south a hundred miles to meet another river, the St Croix, and follow it to the Atlantic.

Everywhere this boundary bisects land it is like this: just a narrow strip cleared in woods, in fields simply left uncultivated. No wall, no fence; you could walk right across.

But to me the US was far away. I wanted it to be. Barry had set the way, my only stipulation that we not cross that border. We'd have made better time if we had: just a short hop to Buffalo, from there swift interstates through New York and New England all the way to New Brunswick or even, by ferry, to Nova Scotia.

But I was carrying drugs that would make me an undesirable alien. And I wanted to see Canada.

Barry chose a route he knew well: the one he'd scooted along in his Shove It, if the other way, in 1986. He'd had a radio then; the Suzuki did not so he sang, smiling. I smiled too.

In Fredericton, too, there was no room downtown, so it was another motel out on the highway. From there the next morning it was straight to Halifax. Only there did we play tourist. We trekked up to the city's reason for being: the Citadel, its guns defending the harbour, Halifax the British Navy's Warden of the North even through World War Two.

That night we found Rumours, the city's biggest gay club, in an old movie house and run by one of Canada's oldest movement groups. We sat in a balcony and watched boys and girls dance. They would later cause a stir among the old local mouvoisie (a Ken Popert term), boys going shirtless though ordered not to, girls soon shirtless in solidarity.

The next day we drove up Nova Scotia and across Cape Breton Island to North Sydney, as far as we could go on the mainland. At 8 pm we rolled the jeep onto the Caribou, two thirds the size of the Titanic, built to break the ice of Cabot Strait -- its namesake sunk there by a German U boat in 1942.

There was ice. We wouldn't see much of it until sunrise but did hear it: great crunches in the air; deep grinding booms coming up through the superstructure.

There were four berths to a room; I fretted we might have to share space. Barry knew why. But in our room it was just the two of us and on one narrow bunk he fucked me hard, my feet pressed to the bunk above. The ice, if not the Earth, moved.

Barry had a sense of occasion about sex: that night on the eve of The Rock; our final night there when he said, "So, do you want one last fuck?" He hardly needed to ask.

We'd had sex along the way -- if more often of my will than his. In Quebec City, half asleep, he got an erection. I took it. In Fredericton I had meant to let him sleep -- but then the bed was shaking: he was jerking off. I made sure he finished in my mouth.

In St John's he woke once with a hard on not too hard; I could make it no harder. I suspect he was bored by then with my endless want of him. But want him I did, having so long wanted him but not having him.

At 7 am, Friday, March 16, we stood on deck and saw through the fog a dock, a few buildings, rock. It was Newfoundland.

***

I want to tell you about this place, quite a bit in fact (if, as you can see, mostly off to the side). I hope you'll bear with me: the more you know of it, the better you know Barry. In my mind, still, they are inseparable.

We were at Port aux Basques, on the Trans Canada Highway still, its Mile One (or Kilometre One) marked by a sign in St John's, still 900 kilometres away. The highway traced almost the same route as the Newfoundland Railway, opened by 1900 not to link far flung outports but to cart people and goods between St John's and Port aux Basques, gateway to the mainland.

Canada had guaranteed the line's perpetual maintenance as part of its 1949 adoption deal; it's now long gone.

As the railway once had, we veered inland at Corner Brook, one of only two big west coast towns. We would not see the ocean again for hours. What we saw were the high, tree covered domes of the Long Range Mountains, beyond them endless low hills, trees, and bog. But for a few small towns that's all we'd see, first seen by humans not that long ago. Even the Beothuks, native to the island if extinct by 1829, had never lived in this vast interior.

We'd had light snow until Corner Brook. There it got heavy. Soon we could see nothing, not even the road if a big rig was in front of us, throwing up great clouds of white. I had brought a map, hoping to play navigator as I had for Paul in England, but Barry in Newfoundland needed no guide.

I contented myself with the names before me, many redolent of dreams: Fortune; Heart's Content; Conception Bay (site of an early failed settlement). I'd later know a boy from Paradise.

There was also evidence of dreams unrequited: Dark Cove; Isle aux Morts (named by French fishermen who knew better than to stay); Witless Bay. That last is famous for gulls and puffins crowding its cliffs each year to breed.

Norman Hay once told me of trying to go see them. He asked a man with a boat, the only way to get there, if he might take Norman out. "Waal," he said, "I think not." Norman asked why. "Ain't no birds, me bye. Wrong season."

By Badger the snow stopped; by Gander we had sun. We stopped for Chinese food at the mall. This was Barry's home turf: he'd grown up nearby; we'd sail past his home town as we pressed on. In time we saw Come by Chance and its boondoggle oil refinery -- less amusing than a later attempt to grow cucumbers under glass.

Now there was the sea, on both sides: we were on the narrow isthmus from which the Avalon Peninsula hangs like a ragged knapsack out into the North Atlantic. Here there were few trees, those not under human protection stunted, bent west. The east wind off the ocean is perpetual, often so fierce that locals say it must surely be rushing by on some better business to the west.

The landscape told me with fierce clarity why this place is called The Rock.

***

Twelve hours out of Port aux Basques and from high on a ridge near Holyrood, we saw in the distance a dappled crescent of light. "Well, there she is," Barr said, "Sin John's."

His pronunciation nearly matched the local one: Sn'Jaahns, not Saint John; that's in New Brunswick. But Barry did mean Sin. Sin City: the place where he had blown out all the stops of his Pentecostal upbringing. We pulled up in Dick's Square at Iona's place, she that friend of Barr's in Toronto. She wasn't home. So we went to the Hotel Newfoundland.

I was zonked. Barry wanted to go find Iona, likely out at a bar: she too had grown up Pentecostal and fled to Sin John's. I slept, I waited; he was back by 3:00 and, yes, he had found Iona.

We stayed with her, if often out for jaunts, one to Cape Spear, easternmost point on the continent, Ireland closer than Vancouver, Toronto more distant than Greenland. The local custom there, Barr said, was to face the Atlantic, pull down your pants, bend over and tell all of North America to kiss your ass.

Another was up Signal Hill, rising 500 feet from the sea. It and The Brow to the south guard The Narrows, sole entrance to the harbour. At the top is Cabot Tower, small and stocky, where Marconi received the first transatlantic wireless message in 1901, the place named, I suspect, for older nautical signals. Barr and I went in, upstairs to a door that led onto the roof. We tried to go out but couldn't, the wind slamming the door back on us.

At a museum near the docks I pondered a big model of the Hood, the British battleship sunk with almost all hands by the Bismarck in the Second World War. Hundreds among its crew had been Newfoundlanders.

One night we sat drinking until 11 at Iona's, with her and her nephew, another good Pentecostal boy. We drank more at Private Eyes, one of the very few gay bars in St John's. By 2 am Barry was staggeringly drunk. I was not: I always held booze better than he did. But then, "getting smashed out of your mind" had a meaning for him that it did not for me.

He and I later went out to a quiet piano bar and had a long talk. (I must have bought him a beer.) I went back to Iona's, Barry didn't. I woke at 6 am. He was not with me. I went downstairs. There he was, dead asleep on the sofa. I woke him. "I was worried about you!" I whined. "Why didn't you come to bed?"

Behind my voice I heard an appalling echo: Randy. I apologized.

He had gone to two bars, sat a long time and then took a walk. He'd wanted to go all the way up Signal Hill, to watch the sun rise. He hadn't, but with that I understood. He needed this for himself, alone. He needed to see Sin John's again.

***

But now it was just St John's, a provincial burg like any other reviled -- and desired -- by outlying locals: the big, dirty, debauching city. He'd gone there a boy, to see what kind of man he might be. He found Wally, the city's best known gay activist. People called Barry then not Barry but "Wally's boyfriend."

So he fled to a place more than 10 times bigger -- and ran smack into me. When he said my full name to people in Toronto, he told me, they often gave a surprised look: How do you know him?

Barry came to know my private self as no one else did; to him my public self didn't matter. "It's you I know, Ricky," he once said. "That's what I care about. All the rest is just bullshit."

Now he lived in a city 10 times bigger still. That was home now; there he was Barry. He was eager to get back. On March 20 he gave me a lift to St John's Airport. I imagined he might just drop me off, but he came in.

We sat around, ate in its diner. I was antsy, he less so but we both knew it was time to go. I flew back to Toronto. Barry went off for a week with his family and then, from Gander via Montreal, New York, maybe Seattle, he flew back to Tokyo.

In that piano bar we had talked about our time together on this trip. "It's a fantasy," he said. "It's not real. Not really." He was right.

Much as I loved the fantasy I knew it was no more than that. Reality was Barry in Tokyo and I in Toronto. We might know each other a long time still, might keep in touch but meet rarely, maybe never.

***

I didn't have a hard time saying goodbye, taking home with me the man I would go on knowing as I had long known him. I did say, as I'd said the year before, that we might not see each other again. He responded just as he had in 1989.

"Now come on, Ricky. No talk like that."

Go on to 1990: Apr-Dec / Go back to Contents

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1990a.htm

December 1999 / Last revised: October 7, 2001

Rick Bébout © 2001 / rick@rbebout.com