|

Promiscuous Affections A Life in The Bar, 1969-2000

1987-1991:

|

"All just bricks & mortar." But home, too, with Terry & Ward, 1982-1989. 784 Euclid Ave, a shot from 1999. |

I thought I'd never have to leave that house. I had not only friendship there, but security.

Now I had to find someplace else. Even if I could find a place I liked, the landlord might not like me.

1989

January through June

I haven't said much about Terry and Ward, my housemates on Euclid Avenue. That's the way it can be with friends so close: they fade into the background of life, so familiar you can forget others might not know them.

Of us, Ward Beattie was the youngest, though he could seem the oldest; maybe it was the cigars. People could find him a stuffed shirt. He was not, but he had been to Harvard. Conversation with him was rich, bracing. Of us he was also most well off, working for a computer consulting firm and later starting his own.

In time he would be much richer, his company swallowed up by Microsoft and Ward with it. Now he's in Seattle. At his send off party someone tried to impress him, casually tossing off: "Well, I am a millionaire." Ward said with a little smile: "Oh. So am I."

Terry Farley first appeared at The Body Politic in 1978, 31 then, a small well built man, handsome, dark haired and rather sober. He might have been a bar clone who never smiled. But he wasn't: his smile, when you got it, was dazzling, his laugh even more so.

Terry came to live at the typesetter. He never wrote for the paper apart from a letter or two, but in 1979 he did make the review section's contributors list: "Tim Guest and Glenn Schellenberg go on dates with Terry Farley."

I did too, if only once to bed: he was playful, snuggly. He was living then in another of those gay group houses, one headed by baker / activist Dennis Findlay. At Euclid we sometimes had breakfast together, he just out of bed and I heading there from a night shift at TBP. Terry would smile at my morning libation: two big glasses of white wine.

***

Cute boys loved Terry, but it was plain Ward who got him. In 1980 they bought 784 Euclid Avenue and moved in together, from time to time taking in a few tenants too.

By then they had taken over TBP's subscription processing from Don Bell, doing it at the university computer centre where both worked. Ward was Terry's senior there, as he could seem at home, though Terry was the oldest of us. Not that you'd guess.

But as their relationship loosened it was Ward, not Terry, who got the boys. Even in better times Terry could feel a bit player on a stage designed and mostly financed by Ward.

One night in January Terry came up and asked if he could sleep with me, just so I could hold him. It was a pleasure, if a sad one: he and Ward had decided to split up.

At first Ward talked of keeping the house and renting it out, except for my place on the third floor. But soon they decided to sell. Sitting once with Ward in the grand living room, he looked around and sighed, "Well, it's all just bricks and mortar. Best let it go." But he was sad at that, so much else let go, too.

It had cost $80,000 in 1980; the renovations -- still not quite done -- another $120,000. It sold for more than half a million dollars. I didn't stay: real estate agents touring people through would say as they showed my apartment, fully equipped now, "You could get maybe $900 a month for this." I'd been paying half that.

Terry planned a move to Vancouver, worried at finding a job. I asked if he'd cleared enough on the sale to tide him over. He told me he'd got $100,000. "Terry, honey," I said, "just go lie on the beach for a while!"

He did but of course found work, still in computers. He's still there; we're still in touch, he and Ward still friends. And he's still gorgeous even, if now, with grey hair.

***

I'd never thought I'd have to leave that house. I had not only friendship there, but security: Ward wouldn't fret my rent if I got too sick to work. But now I had to find someplace else.

Vacancy rates approached zero then. Even if I could find a place I liked, the landlord might not like me: freelancers are notorious for unstable incomes.

Mine was increasingly unstable. I was at ACT most of the time now. I could no longer afford to donate back most of my fees. They were cobbled together from various pots, most pots at ACT for specific projects, the few for general spending running dry.

Stephen Manning didn't want to lose me: my work brought in four times what I was paid. He looked into a grant to cover me, one meant to hire people off welfare. I wasn't on welfare but I'd have to apply. I did try: I wasn't quite poor enough to qualify.

Self employed people didn't quality for unemployment insurance, either. I had no pension, no drug benefits, no security at all. And soon, no place to live. Almost everywhere I looked I found the same sign: No Vacancy.

Once during all this Gerald called and said, "Come over for a drink."

- Friday, March 10, 1989, to Jane:

Gerald lives in one of those very ghetto high rise apartments I covet, though it may yet be renovated out of his price range. We sat in the sunset light coming through his bright blue venetian blinds, split a bottle of wine and reflected on the fate of people like us reared in the gift economy of community work, the movement, TBP. We're not much good at proving our worth to landlords.

Paul and David gave me dinner later and then I went home -- such as it remains, the books and much else packed -- to bed. My pill beeper woke me at six and I couldn't get back to sleep, so I got up and packed yet more, for no more reason than to satisfy the urge to do something aimed, however vaguely, at resolution of all this.

***

As Beepers, we had lived in gift culture. I would find I still did.

In 1985 Jane had put me on to a book, one Margaret Atwood had first put her on to. This passing along was apt: the book was Lewis Hyde's The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property.

Hyde defined "erotic" in much the way I did, his eye mostly on what motivates artists. He studied cultures where status came not from how much one owned but how much one could give away.

He called them "gift cultures." Jane said it helped her see why she'd happily written free for The Body Politic while seeking pay for most of her work. In gift economies the currency is gifts, meant not to be kept but passed along.

We had lived in gift culture. I would find I still did. Michael Lynch offered me Stefan's room (he was away with his mother in California) for as long as I'd need it. Steve Clegg, a sweet, basso voiced bartender at The Barn, Craig Patterson's boyfriend on and off if always his friend, said I could stay with him. I'd have loved to but for the prospect, potentially complex, of falling in love with him myself.

Later Steve alerted me to a vacant place in his building. Then Colin Brownlee told me of one from which a friend had been just been evicted. Then a bar friend -- we'd played a lot at Trax but I never got him to bed -- said he'd been walking by 41 Dundonald Street and the sign there finally read, as it hadn't on my own visit: "Bachelor available."

I put in deposits (the cheques cancellable) for all of them.

***

41 Dundonald Street: "Precisely one of those very ghetto high rises I coveted, Church & Wellesley not a minute away." A shot from Cawthra Park. |

Dundonald came through first. I had hoped it would. I'd have taken any of them but this one I liked best.

It was on the 11th floor, its windows bright with a view to the north -- a joy after touring too many tiny basements. It was just one room with a tiny kitchen and bath, but it was all I needed.

And by then my income was stable enough to please a landlord. ACT's board had built $25,000 into the budget to cover me. I was no longer ad hoc and, thankfully, no longer freelance. Stephen said the figure was too low for a full time post, so asked me to work a short week. Fat chance, that.

That apartment would not only do: it was precisely one of those very ghetto high rises I coveted, Church and Wellesley not a minute away. I got the place a month before I had to vacate 784 Euclid and spent two weeks carting over the most delicate stuff by cab. On April 15, Ward, Terry, and Craig helped me cart the rest, taking just one trip in John Scythes's pickup.

I'd also had time to paint the new place, most of it a sandy pink to catch the light, deep burgundy on two walls marking a corner where the bed would be, sheltered behind bookcases. My biggest piece of furniture, my desk with a return for the computer, took up much of the room. Paul Pearce said, "This isn't an apartment, it's an office!"

I got things up on the walls before I moved in, and with reason: before I'd sleep in my bed there my mother and father would.

***

Only my elder sister, on the phone, raised the prospect of my death. I said I was fine. "But you won't live to be 50."

I said: Probably not.

My parents arrived on April 21, staying at Dundonald while I went back to the one thing abandoned at Euclid, a single bed I'd used with throw pillows as a sofa.

They had been to see me only once before, in 1972. I had visited the family every few years since, but after HIV I was less eager to: I didn't want to go be an isolated Person with AIDS embraced (perhaps awkwardly) in the bosom of The Family. I'd rather have them see my life here, hardly isolated.

They knew I had HIV, but that coming out had been harder than my "show it, don't say it" approach in 1972. It had taken me six months to let on and even then, hoping to ease in bad news, I said only that Philip Berger had ordered some tests. I waited a few weeks more to tell them results I'd long known.

I took them for a chat with Philip, introduced them to people at ACT, toured them around Sunnybrook. We had dinner with David and Paul. In all that, and Canada's universal health care system, they found reassurance.

About my gay life they needed none. My mother's acceptance had grown in part from a sense that her Good Boy must know what he's doing, however odd it might seem. They'd heard all about The Body Politic's trials. I had even sent them "Is There Safe Sex?" with all its dirty words. But I didn't know how much of this they might have shared with the family, beyond my siblings.

On one visit down we'd had lunch with my aunt Alice and uncle Jerry -- I liked them a lot even if they were Republicans -- and my aunt Jeanette. She was divorced, scandalous even then. Jeanette asked what I was doing. "Working for a community paper." "What kind?" "A political one," I said; why get into a big scene over lunch? She pressed: "What kind of politics?" My uncle cut in: "It's political, Jeanette! Political!"

In fact she was the only one there who didn't know what kind of political. I didn't know that. My parents did. My father knew what it was to stand up for oneself; he could be proud of what I did, more proud of all his kids that he ever let on to us. I think he'd have been prouder still if I had fessed up over that lunch.

On this visit my parents had just come from another, in West Virginia, where my father and his 12 surviving siblings (some half; there had been two wives) had just buried their father. I imagined my father had on his mind my own mortality, but doubted he would say. He didn't.

Only my elder sister, on the phone, raised the prospect of my death. She'd had a messy life, also divorced, and tended -- as people often do -- to co- opt suffering as her own. I wasn't suffering, and said so.

"But," she said, "you won't live to be 50." I said: Probably not.

***

|

Unavoidable Idea

|

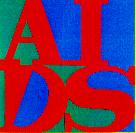

General Idea's AZT: 1,825 pills more than a foot long; five for one day, seven feet each. Those too familiar blue & white capsules, larger than life. As they could so often seem.

That pill beeper I mentioned to Jane, waking me at 6 am, went off five more times a day. It was a little plastic stash, in it my AZT. These things were common now: you could hear them tweeting in restaurants all along Church Street.

Our lives were dominated by drugs, and by drug companies eager to strike fear into the hearts of those who missed a dose: every four hours like clockwork, or else, as if sound sleep had no bearing on health.

The reminder was useful, its tyranny was not: you could safely pop AZT within an hour either way of that maddening tweet.

Some might also take less of it and less often. For many people the dose first prescribed was too high. It had been for me: my hemoglobin count had dropped 40 points, to well below normal.

In January I lowered the dose but added Acyclovir, then thought to work in synergy with AZT (later we'd learn it did not). It cost $200 a month. AZT, much more expensive, I got free as part of its clinical trial. (When the trial ended British Columbia briefly tried to bill people for it retroactively.)

But my Acyclovir had to be paid for and was, for a time by Paul and David.

Some rebelled at these regimens, even doubting HIV was the cause of AIDS. I shared their resistance to medical tyranny, but rarely their alternative theories. John Scythes had one: that AIDS was long term undiagnosed syphilis.

He promoted this fervently at AIDS conferences, his research encyclopedic, his performances dazzling, his ideas worth respect. (Having wowed the pros John loved to let on that he was, by profession, a plumber.)

Other ideas often smacked of "fast lane causes" long discredited. Some went on and on about poppers, even as a direct cause, long after they were known not to be. A life of poppers could likely be immunosuppressive, but to zealots any potential excess had the prohibitionists' usual answer: total control.

Many seemed eager to oust medical tyrants only to enthrone the "lifestyle police."

But most of us, even skeptics, did adapt. The work of General Idea, that Queen Street trio, came to be dominated by AIDS. (In 1994, Felix and Jorge would die of it.) In "One Year of AZT and One Day of AZT" there were 1,830 of those too familiar blue and white capsules. My initial dose put the rate at nearly 2,200 a year.

GI made them larger than life, as they could so often seem.

***

That March 10 bit above to Jane had begun: "Barry left 45 minutes ago." I was still at 784 Euclid then. His visits had got down to maybe one a month. I so looked forward to them that I would go out to the small verandah set in the peak of the roof and watch for him, for that Suzuki coming west along Barton Avenue.

Waiting. Wait: maybe he'll come north up Euclid; I couldn't see down that way. This is silly. Stop it, go read. I would, and then I would go back out to stand and watch, again. And wait.

That day, at 4:45 pm, I stood there to watch him go, stood until his jeep was out of sight. I thought: This may be the last I'll ever see of him. He was due back in a year; I wasn't sure I'd still be alive in a year. I had said that as we parted. "Now Ricky," he said, "don't be silly."

During my too many visits to Sunnybrook in June he'd once tried to call me. I wasn't home, I was at Paul and David's. He spent the night fretting, he scenarizing then: about hearing I was in hospital -- and I hadn't told him. "If that had been true," he said, "I'd have come and found you and whatever shape you were in, I would give you shit."

In that moment I knew I was loved -- in a way I rarely allowed anyone to do. "You're so damned independent," Terry once said. But Barry, yes, I would let Barry love me like that.

Two days later he flew off to Tokyo. Four weeks later Randy followed him. He had at last called the consulate: his drugs were alright, I'd heard; whether he himself was I didn't.

Maybe there was no problem. Maybe he just didn't let on. He had got Barry to cart off some of his drugs.

***

|

For 100 yen: hot men

|

Barry had said he would write. I liked that but did wonder if letters might not be his style. Ten days after he left I got his first, three pages dated March 17, in a small brown envelope with a blue 100 yen stamp, a crane on it. They would become very familiar. I wrote back the next day.

- Thursday, March 23, 1989, 8 pm, to Barry:

How odd your return address looked. It makes me feel the future has arrived. I sent you something today. You'll have to tell me if it gets through customs -- and then I can send more. (It's a surprise. Unless you've already got it.)

I've been doing my community duty. No, not at ACT. At The Barn, judging their Mr Leather Contest. What a night. The place was packed from about 9:00 -- on a Sunday, no less. The beer coolers were empty before last call. I don't think there have ever been so many hot men in The Barn all at once.

Two on stage weren't bad either, especially in what got called "minimal leather." One of those two we sent off to the city finals in April. His name is Calvin; you might remember him as the pretty, dark haired one who often staffed the upstairs cooler bar.

But the best man of the night was another Calvin -- Calvin King [actually, it was Kelvin]. He looked like you, but about an inch bigger in every measurement. Maybe: I can't imagine everything he's got is an inch bigger than you. But a face like yours, intense eyes under the visor of his cap. A good, easy manner, too, and when he danced he bopped his head the way you do. It was a buzz, if a vicarious, sentimental one.

The next night I was back, The Barn back to its weeknight self. I stayed late enough to try picking up David the doorman. Didn't work, but he said he'd take a rain cheque. I'm waiting for monsoon season. Apart from that my love life is much as you knew it -- I mean after it wasn't you any more. You really spoiled me.

Well, I'm off to bed to recuperate from my heavy judicial duties. Tomorrow night I'm off to Paul and David's. I'll tell them about two 7 tatami mat sized rooms, the hunt for cheap (cheap?!) coffee, and friendly former Zero pilots. I love you very much, Barr.

That wasn't the whole letter: I'd gone on longer and would go on longer still. So would Barry, his letters coming often, once three written over five days, stuffed into a single envelope. Our file of correspondence just to the end of 1989 is more than an inch thick.

That surprise I sent was coffee: he had said it cost up to $30 a pound in Tokyo.

I did send more, and more bar tales. Jane Rule still got them, too. But with Barry I could use them to flirt. I had long flirted in letters, of course, but never with such obvious intent.

***

Michael Wade was on AZT, by now having relented to knowledge of his state. I was seeing more of him: shortly before, he had left Douglas Chambers.

Mikey too had felt a bit player on someone else's stage, Douglas's full of fine things. (Douglas once brought a trick home to Laurier Avenue, its living room lined with ancient books. "Nice," the boy said, "but can't you afford any new ones?")

Douglas did, as I did, cast a shadow, if often from too far away: he'd be in England months at a time, with a lover there of many years' standing. Michael didn't mind that but did mind Douglas's absence, feeling ill and abandoned. Douglas led an ordered life, well in his control, but he couldn't control the fact of a lover 20 years his junior having a fatal disease. It frightened him.

Douglas was a good, generous man -- even one who expected friends to presume on his generosity: he less often invited us to the farm than assumed we'd invite ourselves. Mikey lived at 7 Laurier rent free. But material gifts were not the sort he needed.

Before Douglas's last trip he'd asked a young graduate student to stay at Laurier, in the hope of Michael being looked after. Douglas hadn't stated that hope; Michael and that boy didn't share it and got on badly.

In January Mikey had left Laurier and, to make his escape plain, had even quit graduate school. He got a job, his first in a year, doing office temp work three days a week. He moved in with a man named Louis, a waiter, a lovely young busboy from The Barn also rooming there.

Within two months Michael left that menage for a place of his own, saying he couldn't stand ghetto high rise life another minute. "I don't want to see another person," he told me, "who spends more on a hash habit than on rent."

Mikey was often cranky then. Once I suggested going to The Barn. "No! Not The Barn! It's so sleazy." "Alright," I said, "where's less sleazy?" He suggested Colby's. "Michael! Colby's is just as sleazy except that no one there can afford a hash habit without turning tricks."

We went to Trax. I was relieved to see Michael still smoking, imagining how crabby he might get if he ever tried to quit.

Soon Douglas was back, and he and Mikey back together. I later had dinner with them at Laurier, things between them forgiven, I sensed. They'd have a few more months together before Michael fled again.

***

In late May Paul, David and I were off, to England. Paul said I was along as a relief sighted guide, but behind that was a generosity much like Douglas's: he paid my way, the hotels, the food, the lot.

I visited Gillian Rodgerson, there since 1987 working at Gay Times, and met her lover Lesley Jones, whom she'd met at Gay Times. Andrew Alty scooped Paul, David and me off to Kew Gardens, lovely there with no shirt on, running ahead to declaim botanical signs in grand theatrical style.

Paul and David hadn't met him before; Paul said, intentionally within Andrew's earshot: "Ricky, you pick the most handsome friends." He'd later take us to Cambridge, mad for a punt on the Cam. But it rained.

I visited Neil Bartlett at his place in a block of flats built on a piece of the once bombed out East End. I hadn't seen him since 1985; he seemed younger to me, even more bright blue eyed. We talked for hours, smoked too many cigarettes and went out to walk by the Thames, turf rich in history that Neil had down by heart, from Oscar Wilde's time and his own.

We did a few requisite sites. At St Paul's Cathedral the guide let David feel ancient carvings and intricate wrought iron gates and, at Nelson's tomb, told us of his voyage back from Trafalgar, dead and preserved in brandy: "The only British admiral ever well and truly pickled and not able to enjoy it."

On our tour was a handsome blond; Paul and I wondered about him. Leaving St Paul's, David and Paul off in a cab, I headed west through Trafalgar Square and to Brief Encounter, one of the few gay bars I saw on this trip -- and there he was.

A nice Australian if a bit prim: even in the bar he lowered his voice to divulge the word "sex." He and I wandered off to another bar at Marble Arch but there we parted, happily and forever.

***

|

A Bloomsbury turn

|

"...one ought to stand outside with one's hands folded, until the thing itself has made itself visible."

-- Virginia Woolf

to Vita Sackville-West, 1927

London was only part of our trip. Paul rented a sleek Rover and we drove off, of course on the wrong side of the road.

I played navigator, maps in my lap, branches sometimes brushing in my window as Paul nervously hugged the curb. But he got used to it.

In Kent we stayed at an inn begun in 1350. We tried to see Knole, Vita Sackville- West's huge ancestral home; it was closed. Her gardens at Sissinghurst were not and were a wonder.

The next day was Sussex: Charleston Farmhouse, where Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell had lived; then the village of Rodmell and Monks House, where her sister Virginia Woolf had. By then it was in The National Trust, open for tours, so I did get to see that bust over her grave of ashes.

The next day in Hampshire there was a grave of more interest to Paul: Jane Austen's, in the floor of Winchester Cathedral.

It had been Brighton the night before, I too stupid to have brought a guide to its famous gay night life. I did miss pretty boys -- until we got to Devon. Seeking our appointed lodging there we got lost amidst its hedgerows, at last turning down a steep drive -- and there before us, guiding our way, was an angel.

Limpid brown eyes, tousled hair, jeans torn and showing a flash of blue briefs, tanned skin -- the gardener, and our porter. He and I (Paul and David pooped, he on a break) got to settle into an hour of pub talk: the job paid for his studies in photography, in nearby Dartmouth. Bob he was, age 24, born in Gimli, Manitoba. Angel is no exaggeration.

We stayed there two days, Bob alas mostly off in Dartmouth. It was our longest stay anywhere, and the most casual. At Wickham, near Winchester our host was a man often in a crested blue blazer, as if set for a sail on The Solent -- which he was.

Near Bath on the way back it was a gentleman who took in guests at a grand, late 17th century house. Everywhere the food was fabulous. One dinner cost Paul 100 pounds.

***

I could find all this odd: not being treated, Paul's largesse so often lavished on friends, but at feeling a privileged tourist.

The locals, however elegant, were there only to be at our service. We needed to know nothing of them beyond that (though Paul with them was engaging, as ever); nothing of a place (though everywhere we looked things over carefully) but that it was there to cater to us. Like so many tourists, no matter how grasping, we need truly grasp nothing at all.

David, of course, could not look things over. Everything had to be described, explained. I'd never had any trouble being his sighted guide, but being his eyes more fully could be a strain. "How high is this ceiling?" he'd ask. Very; how very could be hard to say.

More than ever I understood words as a mere translation of reality, often a bad one.

Worse was trying to convey anything beyond mere appearance. David had grown up of good, Protestant Toronto gentry; he had brought from that none of the money but much of his sense of the world. At Winchester I described the rood screen, built to separate the sacred chancel from the rabble in the nave. He asked: "Why would they want to do that?"

In Southwark I noted sites that had been bear baiting pits (I'd got that from menu notes at the ancient Anchor Pub). "What's bear baiting?" David asked. I explained as best I could. He boomed out, appalled, "That's awful!"

At Monks House I'd nearly cracked. Heading there, crossing the bridge at Southease over the River Ouse, I'd noted that it was where Virginia Woolf had drowned, a suicide. We got to Rodmell late, had to rush through when, there most of all, I wanted time. And silence.

David asked me: "Why did she kill herself?" I thought: How can I tell you that! How could I possibly explain all that! I said -- in a tone sure to put off further inquiry -- "She was depressed."

***

Later I'd find a few lines of Virginia's, in a letter to Vita Sackville- West, that caught what I'd felt in all that explaining, all those words. It was a gentle critique of Vita's writing (she once said, if not to her, that Vita wrote with "a pen of brass"):

- I was trying to get at something about the thing itself before it's made into anything, the emotion, the idea. The danger for you with your sense of tradition and all those words -- a gift of the Gods though -- is that you help this too easily into existence. I don't mean that one ought to strain, to write showily, expressively, or so on: only that one ought to stand outside with one's hands folded, until the thing itself has made itself visible.

I later told Jane: "How I loved finding that -- 'stand outside with one's hands folded' -- and of course I'd read it before and never noticed." I would recall that line many times, most often as I stood by a dance floor: trying not to rush in on the meaning of what I might see but to wait, hands folded or not, until "the thing itself" made itself known.

Jane, on getting extensive tales of our trip, began her next letter: "What an acute and poor tourist you are!" Perhaps a rude one, too, at least to my true hosts.

At work just after I got back, someone came down the hall from the Archives with a shot of a demo, just a handful of protesters in front of a building. He asked me: "Do you know who any of these people are?" I did.

***

One of them was David Newcome. I knew the demo, too, by the building. It had happened in 1971. There was David visibly challenging a good deal of his upbringing, out on the street with a picket sign -- as I was not in 1971, nor much so even later.

Go on to 1989: Jul-Dec / Go back to Contents

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1989a.htm

December 1999 / Last revised: October 7, 2001

Rick Bébout © 2001 / rick@rbebout.com

Barry's usual stamp & postmark:

Barry's usual stamp & postmark: