|

Promiscuous Affections A Life in The Bar, 1969-2000

1987-1991:

|

|

Baby says bye-bye

|

The line: "suspended indefinitely." But we knew we'd killed The Body Politic.

There was no announcement but word got out -- to the straight media first, our wider body politic left in the lurch. Michael Lynch said he felt "Simply betrayed."

1987

January through July

The January 3, 1987 issue of Xtra, its 67th, now up to 12 pages, carried at the top of its cover a small draw: "Body Politic: 'Bye for Now." The story inside said TBP was in "suspended animation."

That was the official line: The Beep was "suspended indefinitely," the February 1987 issue to be the last -- "for a while." Plans were still afoot: Gerald Hannon even did an ad promising we'd refund the undelivered portion of anyone's subscription fee if asked -- but if they'd let us keep the money we'd sign them up for a brand new magazine.

I shot Gerald an angry note: "Why should they believe us? I don't. And if you can afford the promo hype, a subscriber might say, why did you kill my magazine?" Gerald did admit the effort was "a bit grotesque." (I told Jane Rule I was "tempted for history to compile a list of distinctive Gerald Hannon adjectives.")

We had killed The Body Politic. And we knew it: even our pipe dreams didn't include TBP as it had been. We'd made no formal announcement of the supposed suspension, but word got out.

We had done a press release touting our 15th anniversary: after the 16th CHUM- FM called about that and got Ken Popert. Asked about future plans Ken, as ever honest to a fault, spilled the beans. Jane got called by The Globe and Mail for a comment before I even had a chance to warn her.

The beans should have been spilled sooner, not as a slip but in consultation with the wider body politic. Tim McCaskell, who'd left the collective in August 1986, wrote to say he was appalled that such a decision could be "announced to the straight press" before even our own readers or community heard a peep from us.

Michael Lynch -- he'd been working on a piece I'd neglected to call him about and call off -- wrote, too: "If the Collective had evolved to this point of self isolation in making such a stupendous political decision, this Collective deserves self destruction." He signed off, "Simply betrayed."

***

They were right. But we were tired, most of us, those not tired not able to keep the thing alive as what, at its best, it had been. It had certainly not been its best lately.

The January 1987 cover was a caricature of 15 Beepers, done by Ian King, hired in April 1986 to replace Robyn Budd. A patient man, Ian: he had first applied for the job at the same time Robyn did. A nice man too and not a bad caricaturist; the image was cute.

Too cute. The whole paper had taken on a look just this side of juvenile. That January cover, pink and blue, was headed: "Reason to Celebrate! Ontario says Yes to Rights! We Turn Sweet Fifteen!" No wonder people were surprised to learn the next issue would be the last.

For the final issue I got to write a two page piece explaining our decision. I also, for the first time since early 1985, got to design the cover. Gerald, Robyn and I (she and I with Merv's business if still volunteer Beepers) came up with the concept.

On it was The Body Politic's first issue, November / December 1971, its cover showing people boarding a bus for Canada's first big gay demo on Parliament Hill in August of that year.

Wrapped around that was text in large type. It read:

- This is how it began. Two years after Stonewall, a bunch of people got together to start a small gay tabloid. They didn't really know how to do it. But in a moment that felt fresh and exciting and new, anything seemed possible. They just knew they wanted to. What they made was brash, pig headed -- and vital. It touched more people than they could have imagined in 1971. And it lived for fifteen years.

This is how it ends. The Farewell issue of The Body Politic.

We joked it was like trying to write your own obit -- so it would sell.

A 15th anniversary party set for January 15 went off as planned. Sort of: people were asked to pay $15 to attend; few did. It was less a bash than a wake and not a lively one. As I wrote Jane, it seemed "a model of the paper in the last while: not well done, inspiring not much interest, and probably losing money." We couldn't even throw a decent party anymore.

I got home (actually from a booze can in the same building) at 4:30 am, sobbing so loudly I woke Terry Farley. He let me cry on his shoulder. It was all over.

Gerald Hannon, given the last word on the last page of the last issue, wrote: "I feel now that nothing again will ever be so new and fresh and eager, so pig headed, so infuriating, so clumsy and so young."

About what Pink Triangle Press would go on to publish, he'd be right. Except, too often, for "clumsy."

***

In early January Neil Bartlett sent me a manuscript. Not an article this time; I had no place to publish articles now. This one was an entire book.

- To Neil, January 14, 1987:

The manuscript was my morning reading for many mornings. I got to the office quite late a few times as a result. It threw me at first, maybe because I did what many readers are likely to do: I kept asking it to tell me what it was, to slot itself neatly into some category. The one I had in mind at first was "history": this will be something like what Jeffrey Weeks or George Chauncey or Allan Bérubé might have written.

Of course it is history, but not as they might have written it. Certainly they don't pretend to "objectivity," but neither do they weave the past and the present, oneself and one's forebears, together so directly as you do, making your own discovery of what you're now sharing with us a part of the story itself.

Mostly I came away with a sense of your wonder and love and awe in the face of all of it, the marvellous ordinary facts of our lives, new and yet not new. Of all these I sensed most the love: critical and generous at once; connecting; promiscuous -- wondrous.

In the end my editor / publisher mind went back to asking what kind of book this should be -- not to categorize it, but to sell it. It must not be packaged as "professional" or "academic" -- because it must touch people who would think such a thing is not for them.

It must be for the man whose boots [Neil had told me] you wanted to lick; for the skinny Nordic blond who dances at The Barn with his shirt off and whom I blew with two fingers up his ass in his Maitland Street bachelor apartment last week, on a sofa bed not pulled out into a bed and with Whitney Houston on the stereo and his cat watching.

It mustn't be "history." Because it's much more than that.

***

What is this book? Neil's Who Was That Man? defied easy categories, history but not "history." |

Its publisher, editors & designers clearly hadn't cast worried glances over their shoulders, any more than Neil had. They printed what he wrote, illustrated it as he'd wanted -- & produced a fabulous book.

What that book was was Who Was That Man? A Present for Mr Oscar Wilde, to be published in London, 1988, by Serpent's Tail.

Apparently no one at that press shared my misguided need to categorize: they did call it "Social History / Biography" on the back but they packaged it for popular appeal. Neil had told me of the illustrations he'd wanted -- and there they were. And, as far as I could tell comparing the final text with his manuscript, so were his words as he'd written them.

Its editors and designers clearly hadn't cast worried glances over their shoulders, any more than Neil had. It's a fabulous book.

In that same letter Neil got another story of The Barn (you can see I'd take any excuse, as if I needed an excuse, to tell them).

- There's a busboy there named Martin. I first noticed him for his slack lower lip, astoundingly long in profile against the light of the bar. He's long legged, too, and speedy, lean but full assed, red haired (born in Scotland) and 23 years old.

Busboys, of course, are impossible to pick up. But I ended up at The Barn on a Monday night when almost no one else is there and ended up too at the electronic trivia machine. So did Martin. On Monday he can leave early -- 2 am. And I left with him as he closed the bar with Barry, the bartender (quite a dish himself; he's studying colour theory at the Ontario College of Art, and all this time we thought he only knew how to dance at a beer cooler).

I've never closed The Barn before. It felt wonderful.

Despite that night together, Martin remains a fantasy. There's nothing here to satisfy reason: the first thing he did in the morning was smoke a joint; as I told Jane Rule, I have problems with that even among people who are more middle class.

It isn't even lust: he's delicious, but the sex was torpid (is that a word? well, you get the idea). I think it's a wonder that a kid like this likes me at all. And he does. He sneaks up behind me while he's clearing empties, gooses me, grabs me around the waist and says "hi sexy!" But it's not really sex he's after. I think he's surprised that I like him. And I do.

There are no "prospects" here; in his aggressive / defensive street kid way he's as wary of prospects as I am. But there is this wonderful connection, made across some territory both of us, I suspect, are surprised to find ourselves in.

Martin would stay in my life, if intermittently, far longer than I could have imagined. I still think of him as Martin the Busboy though he wasn't one for long; later he'd drive big trucks. But to this day I don't know his last name.

***

In November 1986 I'd negotiated a contract with the AIDS Committee of Toronto to develop fundraising campaigns and build a donor database.

I knew about fundraising: I'd done direct mail drives for The Body Politic. But databases I knew not, even computers still foreign. I figured I could learn so I bought an IBM XT clone on borrowed money and learn I did, if agonizingly at first.

The computer was at home, not at ACT or Merv's office; they didn't yet have such things. This was good: I could work on my own and, even more blessedly, could call for help when utterly boggled. My housemates Ward and Terry made their livings in databases.

ACT couldn't have afforded me but for that contract, rather an odd one: I charged them $20 an hour but donated $15 of it back; the receipts came in handy at tax time.

Merv's accountant had talked most of us into setting ourselves up as independent businesses, but to be credible with Revenue Canada we had to have clients besides Merv. So I became Rick Bébout Consulting, sucked again into the mythology of small business. I'd escape again later and gladly: it was such a pain keeping receipts for everything from printer ribbons to taxi rides.

"Consulting" was a euphemism: I didn't so much advise people what to do as decide with them what was needed -- and then do most of it myself. I not only developed ACT's donation and membership systems but ran them on my own, at home. Once Merv's company got a computer I was at it endlessly, building and running programs to docket our time and do invoices.

Over the next few years I'd spend thousands of hours writing code, an oddly obsessing task: it could take me minutes to rejoin the real world if someone spoke to me while I was pecking away, lost in the virtual one. But, at Merv's, it freed me in time from work with clients -- all but ACT.

***

|

ACT's place, people

|

The AIDS Committee of Toronto had found quarters in August 1983 at 66 Wellesley Street East over a Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet, its aromas often wafting upstairs. It was a tiny space. Even when expanded to the floor above in 1984, there was never enough room.

There had been only three paid staff in 1983 with 75 volunteers in and out all the time; by now there were nine staff and more than 200 unpaid workers. By the time then current executive director Stephen Manning left in 1991, those figures would be 30 and 400 (if thankfully in bigger digs). The annual budget had gone from $90,000 in 1983 to more than half a million, $300,000 of that at last in government support.

Stephen was a Catholic priest, if not the usual sort: I never saw him in clerical drag. He was adamantly gay, liked making jokes about the Pope. His Holiness would have the last laugh: by the time Stephen left ACT in 1991 he was a former Catholic priest.

He often noted the varied backgrounds of the people he directed: a few religious types like him; feminists who came mostly from anti violence and rape crisis work, and old boy gay liberationists.

The women tended toward counselling and direct care, the men to less touchy feely tasks like education and fundraising. (Cindy Patton, writing later about AIDS organizations, would see this pattern often.)

The gay lib types included a lot of TBP alumni: Kevin Orr; Ed Jackson; Phil Shaw, briefly interim director before Stephen was hired; and Tom Keith, with the paper from May 1985 and now at ACT's front desk. And, if still rather loosely connected, myself.

***

Another felt like an old Beeper: Joan Anderson, chair of ACT's board of directors, its fourth. Michael Lynch had been the second after Bert Hansen who, too, was often around TBP. Joan had been since the late '70s, a volunteer at the Archives.

Almost all Joan's friends were gay; she herself was not. Some people didn't know that; given her work with the community one could see why. Joan had replaced a gay man as board chair after a 1986 flap in which some of the more conservative members, he among them, had left. Joan seemed more truly gay than he ever had, certainly more progressive.

Confidence in her was later more widely confirmed: she would become and remain for years the chair of a national coalition, the Canadian AIDS Society.

My formal role at ACT was administrative, but through Walker Communications I still had a hand in education efforts. In March Eddie and I came up with a series of ads, still pushing condoms if in a simpler and more alluring way.

A photographer we knew, Gilbert Prioste, a lovely man then boyfriend to David Chang, did wonderful shots of men making love. They weren't contrived: he simply had friends who trusted him enough to let him keep shooting while they did what they wanted together.

The shots were grippingly sexy. We used four, all overlaid with the same caption, a single word: "Yes." Below and smaller was one line of text: "With condoms, you're ready for anything."

As I told Jane, "Eddie and I had taken a whole afternoon to come up with the text, and in the end felt quite brazen about a safe sex campaign that said, simply: Yes."

***

When not at home, at Merv's, or at ACT, I'd be found, almost certainly, at The Barn. I was even there on December 25, 1986, the place at last open for the holidays. I wanted to be home for Christmas.

I could still find Martin there. When it was slow he'd squeeze his bum onto my bar stool between my legs and yak. When he'd say he was horny I knew he really meant that he wanted to come home with me and fall asleep.

That's what usually happened: in bed, neither of us had ever come; often we didn't even try. But he was wonderful to hold. I loved being trusted with this wary boy's rich, sprawling body.

- April 3, 1987, to Jane:

The night stretches ahead for work: I don't need an evening out after last night, eventful if not in any particular way. Just the usual and as usual at The Barn, which gave me some people to think about.

The first was Martin. He doesn't work there any more (he fired himself, he said, by failing to come in two nights in a row) but he still shows up just as he used to on his one night off while working there. A lot of bar staff seem to do that. I left him at the trivia game with a blond boy in mascara: he seemed to appreciate that. (It didn't seem politic to ask about his latest boyfriend, in the Don Jail for passing bad cheques, so I didn't.) He and the blond left together.

Liking bar staff as I do (perhaps because they're working, which to me makes them sexy), I started chatting up another busboy. This one is Brent: thin, pleasant and so tall that he has to duck to get in the door. People joke about taking him home and going up on him.

Brent and I have had a smiling acquaintance for a while, but last night the connection was more constant: on rounds he'd stop and talk when I happened to be in the vicinity of an empty beer bottle, or squeeze my shoulder as he passed by. In all likelihood none of this means anything more than that he's comfortable with me -- which is wonderful all by itself.

Maybe I like bar staff because I can count on them being there, being engaging. I like them all the more when their engagingness seems a product not simply of professional niceness but of who they might really be. Brent, I like to think, really is the amiable, attractive beanstalk he appears.

Then there was Don. We've had sex half a dozen times. It's always the same: always wonderful, and I never stay the night. I know nothing about this man but what he likes sexually, and that he looks very severe in a bar but becomes a genial (if essentially very private) pussycat when you get him alone.

Don left before I did, but I later found him cruising the grounds of his apartment building and ended up with him again on the 10th floor -- and again was home by 3:00.

***

|

The "ghetto" comes out

|

The ghetto was not mostly gay. What made it ours was that one could be gay there, openly. We were at home, comfortable with the assumptions of those around us.

If most people there weren't gay, they were never surprised that others sharing their space certainly were.

Don lived at The Village Green, three towers just south of Church and Wellesley. The only thing green about it was a small park with a decorative pool. It had been cruisy from the day the complex opened in the mid '60s, part of a circuit quite busy after last call at the bars, taking in its many storeyed garage and a lane behind buildings on Church.

I'd first found Don there and would again, soon with no idle chat. He'd just grin and say, "Want to come suck my cock?" In time we wouldn't even make the 10th floor: he had a key to the basement lockers. I never knew Don's last name. It occurred to me that I could check the building's directory and find out, but I never did. Donny Blowjob was good enough.

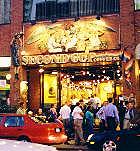

By day the neighbourhood was active too. That same park often saw men in skimpy bathing suits taking the sun, others wandering by for the view. The laneway wasn't busy during the day but Church Street certainly was. The short, wide rise of steps outside The Second Cup -- now so famous that you need only say "Meet me at The Steps" and you'd surely be found -- was never empty, people always there to sip, smoke, and take in the scene.

Gay life had once been kept indoors, or in the dark; now even at noon the whole street was gay, the kind of place where you could be surrounded by strangers but not feel wary. They weren't strangers, really, not even those one didn't know. Yet.

***

I'd become rather a fan of the ghetto, even the notion of it despite its contradictions. A friend later writing on it would define it in the classic way, as an area inhabited almost entirely by people of one kind, Black, say, or Jewish, the original ghettos confining Jews by force.

But a glance on the street could tell me (and some later work I'd do on its demographics confirmed) that our ghetto was not mostly gay. What made it ours was that one could be gay there, openly, unexceptionally.

We weren't locked to the turf, did brave the wider world -- but we could feel at home there, comfortable with the assumptions of those around us. If most weren't gay, they were never surprised that others sharing their space were.

Suburban kids did sometimes harass The Steps, if mostly at night and from the safety of a few tons of steel and glass on wheels. They'd never have got away with it otherwise, not there, though they did on quieter byways.

There were bashings. In August I'd report one to Jane, on Alexander Street, a Saturday night -- significant that -- but less awful than it might have been.

- I was accosted by three kids. One said "Excuse me" and when I hesitated to see what he was on about he leaned on a lamppost, squeezed his crotch and said "Come on and get it." I stepped off the curb and tossed off a casual "Fuck off." One of the others brought his leg up and caught me with a swift kick in the chest.

It must have connected just as the swing had peaked -- I simple walked through it and kept walking.

There was a moment when I thought, well, this is it, and glanced behind me, but they weren't moving and I just kept walking, I don't think any faster than I had been before. Church Street, with a 24 hour Mac's Milk and its usual gaggle of gay loiterers on the corner, was only a hundred yards away, and that, perhaps combined with the fact that I'd had a few drinks -- but more with my sense that this was my space -- gave me a bravado I'd never have anticipated. I literally sailed through it.

Still, I was very lucky. I did have fantasies of remorseless murder -- what a blessing we can't carry guns -- but I cleared it all from my head by walking down the same street at the same time the next night, when of course it was again as mine as it had ever been.

***

One day a year-- though now it was more like a week -- that turf was indisputably our own.

- June 29, 1987, to Jane:

Tonight The Globe had on its front page a nice picture, flagged "Gay Pride," of the lead banner in today's march. (So odd to be involved in something and then pick up a newspaper reporting it before you go to bed.) [The Globe and Mail's "bulldog" edition appeared late at night, dated for the next day.]

The caption said 9,000 people took part; that may be a reasonable estimate of the number who marched, but the crush in Cawthra Park makes me suspect the total was much higher. For a while in spots there was simply gridlock: you just couldn't move. Ninety different organizations had display tables.

The local TV news put everything into the expected frame, saying that this year's celebrations -- not just here but across the States as well, 100,000 in New York, 250,000 in West Hollywood -- were shadowed by the spectre of AIDS.

But that hardly seemed the case here. The mood was buoyant. Not only was the park full of balloons and rainbow flags, but the balconies of many surrounding apartment towers were similarly festooned. It really is gay Christmas, more so every year.

On the way home tonight I walked back up Church Street and found the mood still there: lots of T shirts saying "Rightfully Proud"; people smiling at each other more easily than usual; the crowds gathered outside Chaps and Komrads after closing larger and more active than on the average Sunday night.

Even in the middle of a weekday Church and Wellesley is very much gay downtown, not just with men sitting on The Steps or the hair snippers at Magicuts next door assuming one's homosexuality in their small talk almost as readily as if they had found you in a bar; but with Gillian Rodgerson [who lived there] unlocking her bike and Danny Cockerline hula hooping on his deck beside the ACT office and Kevin Bryson getting a razor cut at Mario's right on the corner.

At 2 am the 24 hour Superfresh Mart [aka Superflesh Mart] is full of men coming from the bars to buy breakfast (I among them), moving out through the clutch of defiant queens hovering outside. But tonight it was even more ours. And more relaxed, too.

Later this year an idea would be floated that future Pride fests should be held away from Cawthra Park, now far too crowded. Before 1984 they had been: in Grange Park down near Queen West in 1981 and '82; at Queen's Park for 1983.

But now the very thought seemed absurd: Church and Wellesley was home. In time Cawthra Park would be no more than rest stop on Pride Day, display tables, beer gardens and performance stages stretching nearly a kilometre along Church and even west along Wellesley, with the smaller streets over to Yonge full of revellers.

In time there would be nearly a million.

***

At the end of June, Gerald Hannon at last left the staff of Pink Triangle Press, replaced by Colin Brownlee, a handsome, hyperactive young man with a beaming smile. He'd put it to good use, selling advertising for Xtra.

Colin was the first person ever in that job (nearly all of us had once been stuck with ad sales) who actually liked it. No -- loved it: his entrepreneurial energy became legend. If Ken Popert was custodian of the Press (a role he fills to this day), Colin would be its engine of enterprise. In time the Press would be rich, almost embarrassingly so for an organization still not for profit.

Gerald would go on to freelance writing, sometimes a decent living though when not he plied another trade: at the age of 43 he'd become a prostitute (a real one, not simply a journalist). For a while Colin would work with him, their team act on call to any john who might want one.

To celebrate Gerald's newfound (if insecure) freedom -- and his birthday -- Michael Lynch and Bill Lewis threw a party. The two had been friends, not lovers, for some years and since early 1983 housemates, though each as if in his own house. They'd bought a small three storey Victorian at 8 Ross Street, renovations tucking into it two residences, each as if by magic occupying two floors.

At the main entrance you could go in one door to Michael's place or into another and upstairs to Billy's. The spaces were entirely separate, the second floor between Bill's kitchen at the back and Michael's loft bedroom / study at the front divided by Michael's living room, two storeys high. The place was so amazing it had been featured in Toronto Life.

The back room on the first floor was for Michael's son Stefan, now in his mid teens. Opening out from it was a patio, and a garden both Michael and Bill tended with great care.

It was there we gathered to fête Gerald. We'd been asked to bring a piece of his writing, the more embarrassing the better. We joked we'd come up with his classic one word paragraphs or something "deliciously dirty" -- that phrase itself typical Hannonese.

Alan Miller found at the Archives a disk holding one of Gerald's unpublished works: a Harlequin romance. He used the computer to check word frequency: "sex" never appeared; "sweater" did three times.

By coincidence Bill Lewis and I chose the same passage, so together we read it out loud. It was from a 1974 piece, formal and stuffy, hardly Gerald's style since -- though its title had a more familiar ring: "Was Christ a Cocksucker?"

Gerald remembered writing almost nothing any of us read and laughed nearly to the point of tears.

***

|

Not my Bar

|

There was Barry, lost last summer, found again. This time it would be no mere high school romance. I wanted every inch, every drop of him.

We never said we were lovers, but we were together often. "Buy me a beer?" he'd joke, always his way of saying: let's talk.

On July 3, I stopped in at Boots. It wasn't a regular stop -- I'd been on my way home from another Gerald fête, in Rosedale. In fact, I wasn't much fond of Boots. But on that night it gave me a surprise. As I told Jane in a later entry of that June 29 letter:

- And there I found Barry, my romance of last summer who has not gone back to Newfoundland as I'd thought he might have. He was beautifully talkative and affectionate, and much to my surprise we ended up here together for the night.

I haven't seen him, but for one night when he was too drunk to remember, since last October. It was very much him simply to disappear as he did, and I know he trusts me because I didn't try to follow.

I had first spotted Barry at The Barn on Friday, June 13, 1986 -- at 2 am to be precise, so I guess it was Saturday. He was leaning against the bar, well across the room but it was empty enough by then to allow a clear view if, in that dark, not a good one: tall, rangy, a baseball cap on his head; that I could tell.

I was transfixed. (Years later a friend would confirm that: he'd been right beside me at that moment. But such is memory -- or transfixiation: I don't recall anyone else there at all.)

And then he grinned at me. Had I smiled first? (I don't recall that, either.) I went over and we talked. He was a bit goofy but very engaging, "a party lovin' Newf" he called himself, here from The Rock just two weeks before. To my amazement I took him home.

We began what I characterized to Jane as "a delicious little high school romance," an affair that didn't much outlast the summer.

Barry once stayed at my place for two weeks, between apartments and looking for a job. He was aimless; I was always working, even at home. One night he crouched beside me as I pecked away: "You've got a lot of work to do, right?" I smiled. "Barry, why are you asking me that?" "Oh, I just thought I'd go out. Not long, just one beer. I'll be back soon." "Hey, you don't have to ask me for permission to go out."

And so he went. It wasn't for long but was more than one beer: coming home he threw up on the subway.

The next morning I asked, "So what was that all about?" "Oh it's nothing. It's stupid. I just do it sometimes." I didn't push. I didn't have to: I knew what it was about.

By then even sex had become a strain, he so gung ho, I so often tired: I took to making him come before we went to bed so I could get some sleep. We drifted apart. In that October meeting, at Trax, he'd said he was going back to The Rock.

But he didn't. We started over and this time it was no mere high school romance. Sex with him was no longer strained: I wanted as much of him as I could get. He once dropped in at the office, grinning, flirtatious; I closed the door, undid his jeans and sucked him, swallowed him, wanting every inch, every drop of him.

One night at my place we fucked so loudly that, the next morning, Terry in the kitchen said, "Well! You boys certainly had fun last night!" I apologized. "Oh no," Terry said, "I liked it."

We never said we were lovers, wary of the status: we couldn't own each other like that. But we were together often, usually at my place. "Buy me a beer?" he'd joke, always his way of saying: let's talk. We did often, if not always.

I once told this self confessed party boy, "I think you're a secret quiet person." He smiled: "Well, you got me there."

***

He always said: "If I ever fall in love, I'll tell you." We were in love, but he meant a lover. In time he'd find one.

But until then -- even afterwards, even more so then -- I wanted him, everything about him: his body, his face, his stance, his dick; his reticence and his passion.

I knew best what he wanted when, in bed, drifting off, he'd reach for my arm and hold it wrapped around himself.

Barry would be the greatest erotic obsession of my life.

Go on to 1987: Aug-Dec / Go back to Contents

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1987a.htm

December 1999 / Last revised: October 7, 2001

Rick Bébout © 2001 / rick@rbebout.com