|

Promiscuous |

|

The deepest quandary Sex itself

Devices, desires,

|

It had always been easier to talk about our right to sex than to delve into sex itself. That risked poking a hole in the barricades where we stood peering out, wary of a hostile world.

Rarely did we dare turn around -- & look in.

1983

October through December

If questions of race, pornography, and power caused quandaries for The Body Politic, they paled against a much more fundamental and newly pressing conundrum. Sex itself.

For years, most of us had stood on the barricades of erotic desire looking out, on guard against a hostile world. As Ken Popert said in his introduction to Gayle Rubin's article on S/M, we less often looked in at our own desires.

Again, there had been some exceptions. Gerald Hannon had done a piece on park cruising in 1976, another with Bill Lewis in 1979. He'd explored sex toys in "Devices and desires" that same year, and in 1981 evoked "hot ropes of piss" at New York's famous sex club, The Mineshaft.

The March cover this year had been flagged: "Faking It: Gerald Hannon on Phone Sex / Finding It: Sue Golding Probes for the Orgasmic G Spot." (Where would we have been without Gerald? Or Sue?) In the summer double issue we did a piece on cruising, calling it "Men looking at men looking at men."

But even those exceptions could be discomfiting to some: fighting for the right to our sexuality was one thing; exploring it, exposing it, maybe questioning it -- what does it all mean, really? -- was quite another. That probing could seem a luxury, what with so many clear battles against oppression still to fight.

It was perhaps even a dangerous luxury: questions about our own sexuality -- not to mention exposure of its full and glorious details (not that they were unique to us, but nice people just don't talk about such things) -- might, as Ken Popert said in 1982, offer "free ammunition to our opponents," poking a hole in the very barricades we stood upon.

Gay is good. Sex is good. It's all just good clean fun. Our rallying cries had been clear -- if sometimes too easy.

In the July / August 1981 issue, Tim McCaskell did a piece called "Untangling emotions and eros." In part it was a defence of the then newly raided baths, if analyzed as embodiments of modern consumer capitalism:

- "The baths are capital's response to the erotic needs of gay men. These institutions allow an almost unlimited choice of sexual styles and partners with an economy of scale which makes meeting people, experimenting, and developing one's erotic life an almost effortless, pleasurable experience.

"...cruising was casual, uncomplicated and to the point. Sex was playful, erotic, and if it didn't work there were no hard feelings, no pressure, no complications."

Tim contrasted this to the emotions he could find at home with his lover, noted video artist and activist Richard Fung. Not unfavourably: how nice to have both; how smart not to confuse them. I agreed with Tim but not entirely. Not everyone had a lover at home; not everyone at the baths was as gorgeous as Tim. Not for everyone is sex effortless, free of hard feelings, pressure, complications.

Yes, sex could be separated from love. But from emotions? Even emotions about oneself? When I laid my body on the line, it was not Tim's body I had to offer. Not for nothing did I stay away from the baths.

|

Romance? Just get over it!

"You're in Love.

|

But the articles inside basically said: Get over it. Romance is historical baggage: we're always falling in love with love, with a cultural idea, not really with another person. In fact we saw sex (and much else) bearing tons of cultural baggage: what we do and what it means to us isn't fixed by nature but shaped by social forces, in many different ways over time.

The idea that sexuality is "socially constructed" came easily to us, resisting with feminists the notion that biology is destiny, that women exist to make babies, that sex separated from procreation is "unnatural." We even accepted (in theory, if not always in political practice) that "homosexuality" and "heterosexuality" are not inherent states, but social definitions created by the "dominant discourses" of psychiatry, medicine, and the law.

In short, we were all disciples (some more fervent than others) of philosopher Michel Foucault: author of (among much else) The History of Sexuality; guiding light of social construction theory. In 1982 we got to meet him, here in town teaching for a while -- when not at The Barracks or The Barn.

One night at The St Charles Robin Hardy dazzled him with a bit of local tavern culture: shaking salt in his draft and smacking the glass down hard on the table to give the beer good head. "Foucault's eyes bulged," Robin wrote later, "and with the kind of disordered panic that the French reserve for the gastronomically incorrect, he began to sputter and ask questions, fascinated and perhaps repelled by the notion of salt in beer."

Michael Lynch hosted a more polite fête, Foucault student Bob Gallagher playing chaperone. We called it "the party with God."

In talk about sex around the paper, we were often chided by our most fervent Foucauldians for using the word "desire." It smacked of "innate" drives, of "natural" forces anathema to good constructionists. The correct word, we were told, was "pleasure." Well, fine. But what about desires that are not always a pleasure? What about love and pain and loss and longing and all that?

My response to social construction theory, with which I largely agreed, came to be: Sure, sexuality is socially constructed, but that doesn't make it easy to deconstruct. And hey: what is it constructed from?

|

"Safe sex"? Who knows? But just in case...

Don't -- Don't -- Don't!

|

There was willful ignorance in advice that saw erotic acts as no more than things people just happen to like, & with a little willpower could give up.

Sex acts are not mere plumbing. They embody deeply seated desires -- & the meaning we bring to our desires.

In the December 1983 issue I did TBP's second major feature on AIDS, a five page, text heavy piece called "Is There Safe Sex?" Many thought there was and felt free to tell us how to do it: the subtitle was "Advice on advice on avoiding AIDS." This is where I got to recount that tale from England in 1975, where my bedmate had fled gagging to the bathroom after I'd come in his mouth. Would his panic be justified now?

I looked at theories on the causes of AIDS, including one Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz put forward in their booklet, How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: that AIDS was caused by repeated exposure to a common virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), "against a backdrop of mild immunosuppression caused by exposure to sperm." This "overload" theory was a minority view, most researchers convinced there was a single viral agent behind AIDS.

No one knew for sure, or what the bug might be. But the epidemiology of AIDS suggested it existed, transmitted in ways similar to hepatitis B. Working with that premise (Randy Coates and Jim Freston, an Aussie friend also in medicine, guiding me through the science), I looked at all the bits of advice we'd heard so far, taking each one apart. In condensed form, it went like this:

- Limit your number of sex partners: Bunk if you're in a big city where lots of gay men might be infected -- though government health types were still saying it. Choose sex partners carefully: They said that, too -- total bunk; people don't wear infectious agents on their sleeve.

Avoid exchange of body (more often "bodily") fluids: What, snot? sweat? Let's get specific about what fluids and what exchanges.

Sucking cock: The jury's out, but it likely entails little risk. Fucking: Very dangerous without a condom. Fisting: Don't fuck afterwards. Rimming: High risk for lots of other STDs but for AIDS, unknown. Pissing: On the skin, likely no risk; internally, less certain. Kissing: No risk -- and get rid of those antiseptic lozenges; viruses ignore them and bacteria just get used to them.

Touching: Yes, by all means, touch. Toilet seats, door knobs, drinking glasses, gay waiters (on the job, that is): My dear, just get over it! Many still had not.

I was working with a premise, not an identified virus. But that premise proved correct: many years on, almost all my points remained valid. In fact, research would prove most sex acts -- apart from fucking without a condom -- less risky than they were thought to be in 1983.

But none of that was my primary point. I did want to answer some questions about AIDS (where I could). But, even more, I wanted to question the kind of "answers" already being foisted on us.

- If you want my advice: don't seek advice. Seek information. ... It's not impossible that you may already know more than the doctor you consult. Don't be afraid to ask: doctors are not gods, and good ones don't pretend to be. [My doctor Philip Berger taught me that.]

And remember, too, that you certainly know more about your own sex life than any doctor. If you find yourself getting more advice than information on which to base your own decisions, question it: ask your doctor how he or she thinks AIDS is transmitted, and how that relates to the advice being offered.

I also wanted us to respect our sex lives more than some advice givers did.

- There can be a certain willful ignorance in advice that treats the psychology of desire as simply a matter of things people just happen to like and which, with a little willpower, they can give up. In the midst of an impassioned sexual encounter, swallowing cum or spitting it out is not a minor technical detail, but a matter of deeply seated desire. ...

Satisfaction and fulfillment have a lot to do with what particular sexual acts mean to each of us.

Keeping love domestic keeps everybody else "other," foreign, not worth care.

I hadn't much liked Callen and Berkowitz's little book, sensing more than a bit of satisfaction in a line there that we'd hear often: "The party that was the '70s is over." Well, at least it was saying how to have sex, not, like so much "advice," spouting an often unfounded litany of "don't... don't... don't." And I did find another line there I liked much better.

- Just before they declare the party over, however, Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz dare to hope that "Maybe affection is our best protection." Maybe. Caring about each other is certainly a healthier way to begin combatting AIDS than is warning each of us to suspect that every man we might desire is a walking carrier of death.

I was reminded of a scene I had recounted to Jane in a letter a few months before, talking with Ross Irwin at Buddy's. About love.

- After many beers I blurted out, "I wonder if we'll ever find different ways to define love." (Many beers.) Or "promiscuity," a word always taken to mean indiscriminate sex, not indiscriminate love.

Ross talked of being at the baths, realizing that the tenderness and caring he could feel for another man there for two or three hours, a man he'd never known before and likely wouldn't see again, was as real at the time as any he could have felt for anyone.

He said we think too much of love as this private thing that has to grow over a long time, and tend to denigrate this short term warmth and compassion as something less real.

I said we had to make love less private. I rethought it and said I meant less domestic, a part of public life, not just a thing that exists behind closed doors. And a thing meant for lots of people, not diminished by the fact that it's not mostly for one of those people.

I picked up a man that night, as I told Jane "a tender 27 year old hotel worker who confessed a little sheepishly to being a monarchist." (I'd later know him well, as a volunteer at the AIDS Committee of Toronto.) I liked being with him very much. And, as I said to Jane:

- That I could feel what I did with him and at the same time firmly deny he's "special" to me makes that kind of promiscuity a defence against the foreignness of other people, their bodies, their smells, their bathrooms. Keeping love domestic keeps everybody else "other" in that very direct, physical sense.

|

One (of many)

Same address; shifting scenes:

|

The police numbered these locales: Track One was around Jarvis and Dundas, women working there. This was Track Two -- the name given to that film we got the year before. Malloney's was on the track but not of it, too elegant for trade as I recall. But its new incarnation (I doubt many people there knew of its older one) didn't survive past the end of the year.

Club Domino opened in April at 1 Isabella Street. The site, spreading over storefronts around the corner on Yonge, had seen an early version of The August Club, its more usual home over The Parkside. By October Domino became Oz; later we'd see other names. Bio Rhythm appeared at 19 St Joseph, but was open only on weekends. That street saw later ventures, too, though its oldest would soon be gone, The Manatee closing in September 1984.

Two big new bars with dance floors came on the scene this year: Cornelius in February, on Yonge just north of Wellesley; and Chaps at 9 Isabella, former site of The Hot Tub Club, raided in 1979. They became hugely popular and I have tales of both. But I'll save them for next year.

In September Dudes changed it name to The Crow Bar. Yes, two words; there was a crowbar, steel variety, used in its ads. Later they added a sneering man in a construction helmet; maybe they were after an even more butch clientele. If so it didn't work for long: The Crow Bar would close in August 1984.

By late 1984 The Albany would be gone, too. So let's take one last look, inspired by Jane Rule.

She had done an essay for us on that messiest theme of the year, pornography. In it she talked about war, appalled not just by the violence men could do to women and children but to each other as well -- and with society's glowing approval. "I remember, with horror," she wrote, "the gold stars in windows marking proudly a house which had lost a son, brother or father. I remember, with horror, a mother proudly receiving her country's honour for having 'given' five sons to victory."

- October 3, 1983, to Jane:

The material on war is very good, and, curiously, reflects a feeling I had just last night at The Albany. It's not drawing much of a crowd these days, but in a way that has improved its atmosphere: the bartenders find things so slow that they occasionally come out from behind the counter and join the handful of people on the dance floor.

One of them is Carlos, whose intense Latin beauty could be taken to dictate that his role in clone culture would be to stand sullenly against a wall, attracting lust and giving nothing in return. In fact he's incredibly cheery and physical, rubbing up against people and grinning as he collects empties, dancing with the ones he knows, taking advantage of the fact that the crowd is small enough that he can relax and actually get to know more.

There's a big video screen at the bar, last night showing a segment of the CBC's news series on war -- tanks rumbling, marching troops, corpses -- accompanied by the dance floor's disco and Carlos, rich, lush, happy Carlos in an ambulatory dance looking for ashtrays to empty.

That anybody could see him as part of that mass of expendable bodies to be thrown into burning fields of mud and machines; that that amazing, warm, alive body could be sent off to become so much carrion -- it was all too much to believe.

Yet, of course, it's not too much to believe: that's how millions of Carloses (if that's a plural) ended up. The horror, I think, is in the massive casualness of it all -- all those thousands of individual lives turned into faceless soldier machines, inconvenient refugee problems or innocent civilian targets.

Carlos in another age could have easily been a Portuguese or Spanish soldier; Michael, one of his dance partners -- a terribly Aryan hunk who works as a stripper -- could easily have been a German one. All that gets lost there -- except when the CBC shows scenes of war over the happy bodies on the disco floor.

It was very odd.

That editing job was easy: I'd loved every word she wrote. Now I was less comfortable: Jane hadn't liked our decision to run the Red Hot Video ad and took us to task for what seemed a cavalier attitude about the nature of pornography itself. Nonetheless, I wanted her to say it.

I was wearing many hats: I had opposed that ad but also co-wrote an editorial defending our decision to run it; I was an editor; I was Jane's friend. I had never offered her substantial criticism of anything she wrote. Editorially I'd never had to; politically, I didn't want to.

This time I did, in part to point out errors of fact -- many were flying around, easy to take as true -- but mostly to alert Jane to places where her argument might be too easily picked apart, many waiting ready with their picks. "All this," I wrote her, "is the price we pay for being tied up together in the work of a movement instead of just being a writer and an editor each doing his or her job. Well, I'm glad for that confusion. I just hope you still are...."

Jane was: she accepted some of my suggestions, others not; the piece ran and our friendship survived.

|

"Porn" vs "erotica": Is there a difference?

Conflicting feminist visions:

|

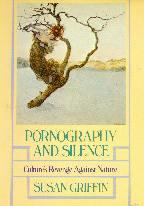

"Whether or not pornography causes sadistic acts against women, above all pornography is in itself a sadistic act."

Susan Griffin

in Pornography & Silence: Culture's Revenge Against Nature, 1981.

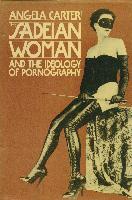

"There is a liberal theory that art disinfects eroticism of its latent subversiveness. Once pornography is labelled 'art' or 'literature' ... ordinary people will avoid it on principle, out of fear of being bored."

Angela Carter

in The Sadeian Woman & the Ideology of Pornography, 1978.

Many letters about the Red Hot Video ad had made a distinction between "good" erotica and "bad" porn. The crux of the debate (for feminists, not the right wing) was power. "The definitions of erotica and pornography have been made clear," one letter said. "Pornography is misogynist and depicts a power imbalance, while in erotica, power is equalized." Some offered definitions of erotica that excluded all but the most insipidly "tasteful" Bambisexuality.

I was struck by how certain these letter writers were about what they knew. "Anyone," I wrote, "who thinks he or she already knows all there is to know about 'erotica' and 'pornography' is never going to know much more about his or her own sexuality."

Is there any such thing as sex freed from the "taint" of power? Would a truly disinfected erotica be boring? I suspected so, and asked why. "Is it because we know from our own lives that sex and power are indeed interlinked?" Not just social power, certainly open to abuse, but erotic power: complex, vibrant, rich.

These ideas also came from feminists, mostly lesbians exploring S/M and willing to talk about it.

But my true inspiration for this piece -- the piece perhaps an excuse to relate that inspiration -- was a wonderful night with a glorious young man.

- Last night (as I write this) I was in bed with a man.

We'd ended up there after an evening in a bar -- an evening that had its fair share of "provocation" and "innuendo," thankfully [one critic had used both terms in a definition of pornography] -- and at one point he was on top of me, holding himself up on his arms so I could see his strong shoulders and chest, his face rising above me. Still in his jeans, he was slowly thrusting his damp, urgent crotch against mine.

Provocation, indeed. I wanted to be overwhelmed by him; wanted to submit to his radiating, restrained powerfulness. I wanted him to fuck me. (He didn't, but that's another story.)

Power -- intensely affecting, desire provoking power. His, over me, at that moment.

But is he really more powerful than I am? Well, let's see: I'm older than he is, and probably more secure in sexual situations, but then he's gorgeously hunky, which I'll never be; he's been helping me with work that I know a lot about and he's just learning, but then he's also working on his BA and I never got a degree; he's bigger and stronger than I am, but then it was my apartment and I knew where the lube was. (But no, I didn't fuck him, either.) And there were times when I was hovering over him, his body arching up, mouth slightly open, imploring, reaching for touch.

We're both male, both white, both in more or less the same position financially. Are we "equal" in power? On balance maybe, but in many specifics, no.

And we took both our equalities and inequalities to bed with us, playing some out perhaps, but definitely playing out shifting imbalances of erotic power, with energy, warmth, resistance, submission and domination moving back and forth until we fell asleep tangled up in each other.

It was wonderful sex.

I didn't tell his name. But lovely production volunteer John Flack knew who he was, and enjoyed me telling the story. I still see him around, still lovely and vibrant and strong.

On reflection, that's what I've always liked best about promiscuity, of both sex and affection: all those lovely men I came to know in ways I might otherwise have not. Each time, I learned something new.

Go on to 1984: January through June

Go back to: Contents page / My Home Page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1983b.htm

December 1999 / Last revised: June 17, 2003

Rick Bébout © 1999-2003 / rick@rbebout.com