|

Promiscuous |

|

Gay consciousness (& not)

Cabaret:

Not So Gay?

Ed Jackson also reviewed A Not So Gay World in The Body Politic, # 7. See Canadian Content? on the CLGA site.

|

(Non)career moves

I had some other published stuff under my belt then too, if less relevant to this tale.

In Sept 1970 writer & editor Jim Christy asked me for an essay for a collection by Americans who'd come to Canada during the war in Vietnam. I did one, popping off mostly about this country -- which I'd know for all of a year; a bit embarrassing to read now. It was published in 1972 by Peter Martin Associates: The New Refugees: American Voices in Canada. Notable among its contributors: Doug Fetherling, who went on to a prolific literary career (if since calling himself George).

Randall Ware (then manager of The Book Cellar; later with the National Library of Canada) was among the founders of Books in Canada in 1971 & asked me to write for it. In the May 1971 Introductory Edition I did a review of White Niggers of America, written by Pierre Vallières's, a member of the Front de Libération du Québec, while in prison. (Years later he'd come out as gay.) In the Dec 18, 1971 issue I did another, on Joseph Schull's Rebellion: The Rising in French Canada 1837.

Finally, in PMA's Canadian Reader I reviewed Ronald Sutherland's Second Image: Comparative Studies in Quebec / Canadian Literature.

All Canadian stuff: the passion of a convert. But that was the last of my published work -- until I got to The Body Politic in 1977.

1973

-

Monday, January 1, 1973, 12:40 pm:

Another year. I have been away from diary writing for so long that I thought I should simply sit down here and do something. I have left the typewriter sitting out on the table for the past few days, just to see what it might drive me to do. (Drive? Sounds as if I might have as easily been driven to smash something....)

Nineteen hundred seventy two was the year of The Open Gate, of Cabaret, and of breakfast at Fran's. It was the month of the move, the week of the kids, and days and days of little decisions.

So, I began 1973 looking backwards. The Open Gate sat on my shelves with other books on the city's architecture and history, gratifying but behind me now. So were the kids and the move, or the month of moves: John and Bill's, Alvyn and Flav's, not just changed addresses but changing relationships. More moves would come, my own included, taking us away from the life we had shared on Spadina. Even, in time, away from each other.

Cabaret was very much our film of the year -- even, it could seem, of our lives. The Broadway production had come earlier (hence PJ's number at The 511 on that night in May 1971), but the film had been released in 1972.

We saw it often, bought the soundtrack and learned it by heart, transporting ourselves to the Berlin of 1933 with Liza Minelli, Michael York, Joel Grey and ultimately Christopher Isherwood, who had lived the story and written it down. I went on about it in that same journal entry:

-

Cabaret brings to mind Flav, gay consciousness, and things beyond. It was alive, and it knew that to be alive was to struggle, to know one's senses, to get a little dirty, to gleefully shout "yes" in the face of "no" and to go on -- living and doing -- all as matters not of great and long suffering, but as matters of course.

The decadence of the period is presented as something still very alive, alive at all levels, aware of its glamour and its filth, lush, sensual, of both the head and the body. And rising to challenge this decadence was the pure, clean fire and steel of the Nazis.

It was in this, rather than in the one little homosexual affair of the plot [between a German aristocrat and Michael York's character, based on Isherwood himself], that Cabaret was a gay movie. It placed on the side of good the whole body experience, the sensual, even the dirty, because what opposed it was mechanistic, repressed and inherently far more dangerous to the human spirit than a little loose screwing.

Cabaret succeeded as a gay film by not trying to be one, letting its sensibility carry the message, not a few stock "gay" characters.

The other famously gay film of the day, Sunday, Bloody Sunday, did nearly as well, its on screen kiss between two men a sensation at the time. And it had Peter Finch and Glenda Jackson to boot, a grippingly intelligent script and lines I would long remember: "You think it's nothing, but it's not nothing"; "Who wants half a loaf? But I loved him."

Still, that tale of a straight woman and a gay man in love with the same gorgeous if maddeningly vague bisexual artist could, if better done than usual, seem a "social problem film" not unlike the few others allowing us gay characters -- their sexuality the "problem," their lives evil, or pathetic, or both.

The '70s did see some films surprisingly radical in retrospect, not so much portraying gay people as giving play to queer sensibilities. The Rocky Horror Picture Show, cult rage film version of the British stage hit, gave us that "sweet transvestive from transsexual Transylvania" who, finding heartland naïfs Brad and Janet, happily debauches both. And they love it.

Myra Breckenridge, based on Gore Vidal's novel, was a camp revenge on both Hollywood and Middle America, its climax Myra / Myron's dildo deflowering of a Southern California stud and the bedding of his "chick" too. This in 1970, with Raquel Welch, Farrah Fawcett and, best of all, Mae West.

By the mid '70s English filmmaker Derek Jarman would give us Sebastiane -- hardly Hollywood thank god if hence hardly seen; some homos of the day who did found it odd (all in Latin, for one thing), its sensibility hard to grasp. Jarman's Carravagio and Edward II came later, his vision by then easier to recognize: one deeply homoerotic -- if to many gay people still foreign.

Mostly, though, we'd see little else so fantastic -- literally; even subversive. The late '70s would give us pathological perverts, by then not sad cases but sadistic killers, in Cruising (fags) and Windows (dykes) -- both met by major protest.

Pushed to portray "real" gay people, liberal movie makers would be careful, even earnest -- partly in response to those pushing: the growing and often deadly earnest gay movement, demanding "positive role models." In 1981 Hollywood would brag of its bravery, Personal Best and Making Love casting the likes of Mariel Hemingway and Harry Hamlin as homosexuals just like nice, normal folks -- bland, safe; subversion the last thing on their minds. They made Rocky's Dr Frankenfurter, Myra, and Cabaret seem revolutionary -- if a revolution lost in time. ("Time Warp" indeed.)

We wouldn't see anything better until the mid 1980s, when films like Parting Glances, Desert Hearts, and My Beautiful Laundrette were heralded as "The Gay New Wave," giving us characters whose sensibilities -- and real lives -- we could recognize.

My other thoughts on gay consciousness came from books. Sexual Politics had paved the way, Kate Millett not yet out but her sensibility clear.

I wrote then that I'd not got in with the gay movement because it seemed to me so little concerned with "what I think is the most important aspect of being gay: consciousness, gay culture, not a subculture so much as a way of thinking, of reflecting the whole world." I'd had a brief affair by then with a man who once said that if he were straight he'd be pretty much the same person. I found that imperceptive to say the least, perhaps even a bit deranged.

-

I read Dennis Altman's Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation and found it posing the problem of liberation through homogenization vs liberation by identification, without really answering it one way or another. [Dennis, a peripatetic Australian, would write many more books, often criticized for their chronic "on the one hand, on the other" approach. But this one was ground breaking, the first to show how clearly our self identity was rooted in our oppression.]

I read Susan Sontag's "Notes on Camp," found them interesting, incoherent, and worth going back to every so often. I read A Single Man [a novel by Christopher Isherwood] to feel gay consciousness at work in fiction, and I reviewed A Not So Gay World, where a total lack of that consciousness showed through in a book about gay culture.

A Not So Gay World: Homosexuality in Canada, was the first nonfiction book on gay life here, its authors pseudonymous homosexuals, Marion Foster and Kent Murray. My review in Canadian Reader, organ of the Readers' Club of Canada run by Peter Martin Associates, was my coming out to Peter and Carol -- and a non-event.

My conclusion to that review: "This is a work worthy of bug eyed tourists in a foreign country. The authors do well to keep their real names to themselves."

|

Café society

"Rimmed & topped

The Fran's chain closed in 2001. The College & Yonge location, on a separate franchise, stayed open; the original St Clair site is gone.

|

A waitress plunked a plate of pancakes before Bryan (to the gang, Vi) -- rimmed with whipped cream, topped by a cherry. He plucked it off & grandly popped it in his mouth. "That should replace the one I lost!"

Even the waitress liked that.

Maybe it was the menu: Franburgers with a delightful twirling relish tray, or Peach Pancake Supreme: "rimmed and topped with real whipped cream." We'd often retire there from The Parkside at 1 am, with friends, usually finding more, with the inevitable drag queens and a languorous black waitress tolerantly blasé at the lot of us.

Breakfast -- brunch really, at 1 pm on Sundays -- was at the original Fran's, at Yonge and St Clair. At first we made dates for it but later we'd just show up to join whoever was there, a few times only one or two others but sometimes more than a dozen.

Bill Rowe and Flav attended early on but soon drifted away. More regular were jewellers Terry and Bill, Robbie, Alvyn and his friend RossAnne, Stephen and Malcolm, coupled friends of Terry's -- and a gang of mad Australians. They were from all over the continent but had met in Sydney; then, as Australians are wont, left to travel the world -- London, San Francisco, Toronto all favoured stops, even for a year or two. They all had camp names: Dennis was Denise; Frank was Fran; Bryan was Vi, his mother's name.

The maddest of the lot was Courtney, a real woman, raised so far in the Outback that she'd gone to school by radio. She too would have other names, for a while Samyrra of the Medina of Marrakech, often in Moroccan gear. Near the end of 1973 we'd be the airport, sending her off to marry a Royal Air Maroc ticket agent. She waved the red flag of Morocco in her window of the big BOAC 747, looking like some crazed hijacker

Years later she'd return, as Alaia Alsharif. In 1990 I'd run into her, not sure I recognized her. "Courtney?" "Yes -- but I don't call myself that any more and I don't want to hear it again!"

Courtney had been the chief enforcer of camp. Spying cute boys on the street she'd burst out, "Prits for Fran!" or "Prits for Vi!" I also saw Vi in 1990, by then firmly Bryan, an actor quite successful. He said then that he had resented her insistence: "It was all just a show for her."

Not that you'd have guessed in 1973, Bryan doing Vi with a vengeance. Once when a waitress plunked down a plate of pancakes in front of him, rimmed with whipped cream and topped with a cherry, he plucked that red confection off and grandly popped it in his mouth: "That should replace the one I lost!"

Even the waitress enjoyed that. They had come to know us well, often holding a big table for us in the Andrew Wyeth Room at the back -- perhaps to spare the after church crowd our antics.

I once taped a brunch at Fran's, all of us madly arch if not particularly original, Dorothy Parker, Lillian Hellman, and Barry Humphries's Dame Edna Everage among our mentors. I suppose we were more entertaining to each other than to anyone else. But to each other we were a hoot.

The Divine Miss M:

|

At her concert we were the absolute best thing, my dear. There were other brilliant efforts: a total '40s get up, victory roll, cheap fur jacket; one number all done up in fake cherries.

Oh, the poor straights in the audience!

-

Our Crowd -- which is to say the Expanded Breakfast Group, about 14 in all -- gathered before the performance for a bit of Terry's divine quiche, an Alvyn potato salad, booze and dope [still just booze for me]. All were well dressed, to say the least. Host Bill was conservative blue suit with vest [he'd later become a priest], at least up to the neck, where hung a glittering rhinestone studded white bow tie.

Terry wore his sequin embroidered blue jeans with a little black padded shoulder jacket, belted with a pleated flare springing from the waist and a glass beaded tree on the left breast. His tiny feet were shod in white pedestal come fuck me pumps with blue sequin work crawling up the heels.

Flav wore a simple black jump suit with an open collar from which a growth of brown speckled feathers flowed up under his chin. His face was white, of course, with pink cheeks and pointy red lips [just like Joel Grey's mad emcee in Cabaret] and dark patches of feathers and tufted spikes over each eyebrow. (Mother's millinery feathers come in so handy.)

Alvyn was rather subdued in his brown velvet high waisted pants, orangey yellow frilled shirt. Red glass glittered from his cuffs, a pin in his waistband, and from a small stone pasted right between his eyes. I was rather discreet as well: a simple black turtleneck with black velvet pants, a plain, three strand gold chain around the neck [brass really, the one I'd worn in that 156 Huron photo; I didn't have many bijoux], and cheap, Palm Beach sparkly high heel gold sandals secured to my feet with red elastic bands.

As a group we were the absolute best thing there, my dear. There were a few other brilliant efforts: a total '40s get up, complete with victory roll and cheap fur jacket, and one number all done up in fake cherries. Oh, the poor straights in the audience!

To say nothing of the ones in the subway to Massey Hall. Fran got walking behind one tall, dark boy, avec femme, whose little round ass was so incredible that we all took turns being behind him. Bill said, "My god! Those buns belong in a museum!"

Bette was fantastic, a powerhouse, the best singer / comedienne since Fanny Brice, someone said. She left us totally depleted. We all went to The Parkside afterward and could do nothing but sit and stare.

Flav had got a job with Inner City Angels, bringing supposedly downtrodden kids to culture. I got to tag along, if not a kid or downtrodden then poor enough to appreciate a few free shows.

In February we saw Godspell, giving many actors their start, Andrea Martin, Gilda Radner and Martin Short among them, going on to Toronto's Second City, later Saturday Night Live on American TV. Marty was very cute then; I liked him so much I went back twice. Later we saw Two Gentlemen of Verona, a musical version on tour. I found myself transfixed by a very tall dancer: he could hoist his big lean body up on a pole and hang there, horizontal to the floor.

The cast came out at the end to talk to the kids and there he was, leaning on the arm of a seat just across the aisle from me...

-

...definitely not a case of DLE [Distance Lends Enchantment], looking even better at close range, all 6' 4" of him, blue eyes, short beard and long hair. And from there it went, eventually with him and Flav to The Parkside, it being Ron's (that was his name) third or so visit there during his two weeks in town.

So, to make a long story short: booze, taxi, Aunt Bea's briefly, bed. It was really, really marvellous -- things like "Sexy little bastard"; things like "Where have you been for two weeks?" etc. Etc.

That was a Tuesday; Ron and I made a date for Friday. I didn't want to run into him before that, afraid of breaking the spell. But on Thursday night I was at The Parkside -- and in he strolled.

-

I literally jumped out of my chair in what was probably mid sentence with Frank [Fran; heaven knows not Big Frank]. I can't really recall. Even worse I had to end up just sitting down again: he was going into the bathroom and I at least had it together enough not to follow him there.

But I was up again as soon as he stepped out the can door. Brewster -- who had come in with his fellow members of the beleaguered minority within the minority, that insular little group of gayrads who do The Body Politic -- had in the interim asked who I was getting so excited about, and could he maybe introduce me. To which I could have said much, the little bitch. But all I did say was, "We're already quite well acquainted, thank you."

I did finally get to Ron. He'd been invited to a cast party on Friday night, wasn't sure he'd go but would call to tell me. He did: our date was off.

I had been a bit dejected at The Parkside, watching him leave with a friend, but then thought: after that amazing night on Tuesday, how could I possibly be sad about Ron? About such rare and wondrous serendipity? A few days later I bought a copy of Frank O'Hara's Lunch Poems (couldn't find Love Poems) and left it for Ron at the desk of his hotel. I didn't put my return address on it. The cast of Verona left for Detroit the next morning.

Rainbowed now, not then:

I've since been told that this flag is not a gay one but the co-op's own: a 7-stripe version used by the international cooperative movement since 1921. But, a lesbian resident assures me, the place is full of homos. |

It can seem odd, looking back, that I had no feeling for my new neighbourhood. Every day on my way to & from work I walked right through what would become Toronto's gay downtown.

In time the words "Church & Wellesley" would be iconic. But it would be a long time still.

The plan there was to rent out loft spaces to artists in the factory wing and live in the offices, a separate building so full of beautiful Art Deco glass dividers and panelling that it was later declared a historic site. He was not taking on the project alone, having met another Taylor, one quite unlike John.

James Taylor was a lean, campy, hyperkinetic man from Midland, Ontario. He would soon join the Fran's brunch gang. On Mercer Street he played romantic lovesick lady to Flav's romantic free spirit, a match doomed to fail and it did. So did the factory rental project.

James met a boy named Brian. They moved to 224A Queen East -- John and Bill's place: they had decamped to rural New Brunswick. Flav eventually moved far east down Queen to the derelict City Creamery, heated only by a coal stove. But it did have a lovely rose garden out back.

My move came in April. The place on Grange was feeling ratty and had been very cold that winter. I was making a bit more money now; again, I could do better. I found a place more than a mile northeast, at 477 Sherbourne: one of three big apartment blocks dating from 1913, called The Ernescliffe.

My place was five floors up, out of basements at last, the view from its north windows going on for miles over a big vacant lot. Within a few years that lot would hold the three huge slabs of St James Town West.

St James Town proper was already there, just to the east: more than 12,000 people on 30 acres of land, the most densely populated place in Canada. Its dozen white towers, the tallest 33 storeys, had seemed a posh address to some gay people when they opened in 1966, but the area had fallen out of favour.

I had two spacious rooms, one a kitchen, the other big enough for a desk, a sitting area and a double bed (at last). By then I was tired of white, painting the place chocolate, vanilla, avocado, and a yellow the paint chip called Sunshine. I built the desk myself against a wall, and book shelves surrounding it. I liked it well enough, but there were times when it just didn't feel like home.

-

Monday, June 11, 1973, 11 am:

I am in an uncreative time. A suspended time, a time between. I like my apartment. I have laboured to like it. But I don't connect it with the building it's in, or the streets on which that building stands. I have no feeling for the neighbourhood. And there is nothing terribly familiar to go back to, or at least no one, in what was our territory. We are scattered.

Looking back on 156 Huron, its days, its people, I can get the feeling that nothing like that will ever happen in my life again. It's possible that I will never put on whiteface again unless as a forced activity, an attempt to recapture the symbols of something for which the substance no longer exists.

My life here could almost be defined in terms of before, during, and after Spadina. I have had lots of company in this place, which didn't happen at 8A Grange. Grange was simply a minor annex to 156 Huron, which is where (or from where) things really happened. But I have no other address now, just this one.

It could be a better thing for me, but it hasn't jelled yet. It's a bad time for jelling. It's too hot. And too temporary. Times between, indeed.

It seems odd, looking back, that I had no feeling for that neighbourhood. Every day on my way to and from work, I walked through the intersection of Church and Wellesley, later famous as the heart of Toronto's gay downtown.

But it wasn't that then. Gay people did live in the towers all around it, not that anyone much noticed. In time the very words "Church & Wellesley" would be iconic, like "The East Village" or "The Castro." In time -- but it would be a long time still.

On those walks I would often see, near Queen's Park, a boy on a bike, the same one day after day. We started smiling; soon he stopped and we talked. He was at the university's architecture school. I'd later run into him at Eaton's, selling sweaters over the Christmas holiday. In time I got him home.

Often. He always asked me to shave beforehand, in bed to wear a T shirt. Maybe he was, as we'd later say, a bit "conflicted." I didn't mind. He was otherwise cheery, a succulent boy avidly suckable. I always made him come.

A few years ago I saw a TV program about a big architectural competition out west. And there he was, working for one of the most prominent design firms in the country.

|

Sci-Med / Fort Book

University of Toronto libraries:

|

He looked in a small tizzy, coming I knew from interviewing a job applicant. "Oh god," he sighed. "Not another one!" Which meant of course that he had hired another homo. It was, as I also knew, Paul Pearce.

Paul told me years later that as his supervisor I let him get away with almost anything. I don't recall him giving me much grief (certainly not compared with another stack rat who was in love with me, I decidedly not with him), and it was there at the library that Paul and I became great friends.

We'd go for dinner at the Tarrogato, one of many Hungarian restaurants to have sprung up on Bloor Street after the Russian invasion of 1956. The waitresses there had odd, open toed white shoes tightly laced up their ankles, and a single stock line whether taking your order or delivering it: "Yes please."

Over our goulash, paprikash or schnitzel we'd drink between us a full litre of teeth creakingly dry Szekszardi, or Egri Bikaver -- "Blood of the Bull." Paul would later and famously be into vintage Burgundies and Bordeaux.

More often we had chicken curry or mulligatawny soup -- the usual fare in the collegiate Gothic splendour of the Great Hall at the university's Hart House. The cans there were notoriously cruisy but I never cruised them, having enough fun with that lunch crowd: Bob, Dan, Paul, sometimes Alvyn, and Bert, a hunky redhead graduate student from Louisville, Kentucky.

Bert popped vitamins at every meal. "This," he'd say of one, "is to put lead in mah pencil." I once got to discover that what he had, while firm enough, was nothing like a pencil. But the greatest revelation of that night was what a gentle sweetie bodybuilder Bert was in bed. After The Open Gate came out he sent me pictures of the great Art Deco station in Cincinnati, even inviting me down to see it and the Kentucky Derby, too.

I didn't go, but I did relish Bert's affections from afar.

In June I went by train to visit Bill and John in New Brunswick. They were at Shamper's Bluff, overlooking the Long Reach of the Saint John River. Freeman Patterson had grown up there, and there now ran his own photo school. John was working with him, Bill sitting hunched as ever, tapping away at his artwork, but this time in a tiny cabin once part of a motel.

I did five handwritten pages on that visit (and a later trip via Boston to see my family): about John and Bill and Freeman, about black flies and black rural nights (I literally couldn't see my hand in front of me, odd to a city boy); about lupins, roads flanked by vast, spiky swatches of purple, red, pink.

I enjoyed it all, wrote it all down. But that was the last entry in my journal for 1973, save a few scratches in November. So from here on I have much less concrete evidence of that year to guide my memory.

Some things, though -- no, some people -- I won't ever forget.

|

More dancers

Gorgeously comfortable & unassuming:

|

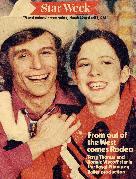

Earlier that June jeweller Bill had brought along a sparkly little guy with sandy blond hair. He was very small, 5' 5" and 120 pounds I'd later learn -- too small, he'd once been told, to be a principal dancer with a ballet company. But Terry Thomas was precisely that, in town on tour with the Royal Winnipeg Ballet.

Terry would be back, with his lover Craig Sterling: tall, classic in shape, a strong, handsome face -- just what one might expect of a premier danseur meant to loft ballerinas over his head as if they weighed no more than a tutu. That's what Craig did, the Royal Winnipeg's romantic lead. Terry did more spunky character roles. They were both gorgeously comfortable and unassuming.

Craig stayed with me one night, just to sleep, getting up after I'd gone to work and leaving me a note: "Thanks so much. Had pleasant dreams and couldn't believe you were gone when I got up. You must be terribly dainty on your pieds in le morning. Oh, quelle next? I'll give my better half your regards."

I recall Terry over a dinner at Robbie's, gently flirting -- so scrumptious I wanted to have him for dessert. I didn't and it didn't matter: I was in love with the moment itself, and with him.

Terry and Craig would stay in touch for years, with postcards sent while on tour: from Buenos Aires (where they noted lots of well packed "canastas"), Mexico City and Havana; from the Kennedy Centre in Washington and Toledo in Spain, from London and Jerusalem and Malmo, Sweden. There were lots of letters, too. My last from Terry would be posted from Des Moines, in 1978: by then he'd have his own dance school in Ames, Iowa.

In 1974 I'd visit them in Winnipeg. Terry toured me through the Royal's rehearsal studio, saying he had a surprise for me there. He disappeared briefly and then popped back -- dressed for his role in Agnes DeMille's Rodeo: a spangly Western shirt with string tie; cowboy hat and cowboy boots, white.

He said nothing, paused, smiled, and then suddenly went: rata- tata- tata- tata, rata-tata- tata- tata, rata-tata- tata- tata, rah- tat- ta-boom! -- his tap dance routine as The Champeen Roper.

It was sheer joy, every second of it and every inch of him. An inch or two taller in those boots.

"It's not going to be me --

|

Vincent Warren

Much has been written about Vincent; I'll list here just what I have to hand.

Dance Magazine

Norma McLain Stoop:

Graham Jackson:

Vincent also appeared on film, most notably in Pas des deux, by the National Film Board's greatest innovator, Norman McLaren (another friend of Norman Hay).

Special Issue: Dance in Canada, Apr 1971.

Vincent features in coverage of Les Grands Ballets Canadiens & its charismatic founder, Russian immigrant Ludmilla Chiriaeff (to whom he once introduced me: "This is Madame").

Also here: the National Ballet, the Royal Winnipeg (with a nice pic of Terry Thomas) & Toronto Dance Theatre -- with a full page shot of Keith Urban in David Earle's "Angelic Visitation #1."

"Spotlight on Vincent Warren." Dance Magazine, Aug 1973.

A splendid profile, with some great pics both on & off stage.

"Vincent Warren: poet in motion." Performing Arts in Canada, Summer 1979.

This piece follows Vincent to "his Elysium" in 1979. Later in this tale you'll briefly meet its author, dance critic for The Body Politic, 1976-82. His book Dance as Dance, collected works from TBP & elsewhere, was published in 1978 by Ian Young's Catalyst Press.

In 1971, flipping through an issue of Dance Magazine at Olivier's, I found him, a full page photo. The caption told me it was from Catulli Carmina, Vincent the principal dancer with Les Grands Ballets Canadiens in Montreal. Olivier knew Vincent, as it turned out -- and then that November, in the photo Flav showed me, there he was sitting in my apartment.

Vincent had been in Montreal on and off since 1960, with Les Grands but also flying off to perform with companies around the world. Before that he was in New York, there at 17 fresh out of high school in Jacksonville, Florida (he would never lose the accent), inspired to dance by the 1948 film The Red Shoes.

Frank O'Hara first saw him dancing with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet. They met in 1959, Vincent 20 years old -- and thus the love poems were born.

But soon Vincent was away, often in Montreal. By the spring of 1966 he had it in mind to return to New York and maybe to Frank. But it was in the summer of that year that O'Hara was killed on Fire Island. Vincent grieved, but he had found a life in Montreal and with Les Grands. He remains with the company to this day.

I spent a bit of time with him in Montreal in November 1972, visiting there with Bill Rowe. Vincent was very engaging but I felt a bit underfoot: Bill was out to make hay and I believe he did. I saw him again in May 1973, here, dancing a lead role in Carmina Burana. We walked city streets cruising Vincent's favourite sights: "Buildings and boys, buildings and boys," he'd say, "I just love buildings and boys."

I'd buy a camera in 1975 -- and shoot almost nothing but buildings and boys.

I did get to spend more time with Vincent later on. I don't recall exactly when; maybe during a stopover on that trip to New Brunswick in June, likely a good bet: the Ocean Limited to the Maritimes originated in Montreal. Or maybe it was later. It doesn't matter.

What I remember for sure is Vincent in his big apartment in a wondrously inexpensive building on rue Jeanne Mance (such Montreal digs long the envy of Toronto). The place was full of things, most covered in dust: artworks signed to him by New York Abstract Expressionists and later artists; memorabilia; many books and many videotapes -- of dance. We sat and watched a few, Vincent knowing nearly all the dancers.

That night he popped a bit of mescaline into my hand. A hit? A tab? I don't know what to call it: I'd never done it before (and haven't since). We were off to The Peel Pub, a noted gay bar. There I held up my empty hand to Vincent. See? I'd taken it.

From there we trekked off to see the late '40s bio of Jerome Kern, As Clouds Roll By, with among other attractions Judy Garland singing (I think it was "Always Look for the Silver Lining") while washing dishes piled to hide her pregnancy, Liza Minelli soon due. Then it was back to Vincent's place and (I was amazed) to his bed. What seemed a mad chorus of pots and pans clanged in my head, keeping time to Vincent's rhythms.

The next morning over breakfast, Vincent talked about his career. His body, he said, was telling him to stop: "Mah butt's gettin' too big." We went next door to visit a friend, Strowan Robertson. There we joined two other men, older and younger, both named Norman, uncle and nephew. I don't recall much of either from that day, but would later come to know the older, Norman Hay, very well.

Strowan had known Frank O'Hara at the University of Michigan in 1950. He read aloud some poems of Frank's that I knew -- or thought I knew; his reading showed me I hadn't until then. Years later I would ask Strowan to write a piece for The Body Politic, reviewing a personal recollection of W H Auden and his lover Chester Kallman. It was such a rude, intrusive book that Strowan nearly pulled out his trump card: he had known Wystan Auden and Chester as well.

Too honourable for a game of tit for tat, he'd refuse to let on.

Terry Thomas, Craig Sterling, & Vincent Warren helped me find my way.

Years later too, sometime in the '80s, I would see Flav walking down Church Street toward me, with a portly gent in a big overcoat. When I got up to them that man laughed and said, "He doesn't recahnize me!"

In that moment I did, the accent unmistakable. Vincent's body had indeed told him to stop dancing. His last performance had been in 1979 at Montreal's Place des Arts, a gala in his honour. Nearly every ballerina he had ever partnered was there, each giving him a rose. Covered in roses at the end he looked, as dance critic Graham Jackson wrote, "like a Romantic poet who had found his Elysium."

Interviewed in Dance Magazine in 1973, Vincent had said of his possible career, however it might turn out: "It's not going to be me -- it's going to be dance!"

That day I saw him he was in town to buy books: he had become the librarian of L'ecole des Grands Ballet Canadiens. Last I knew (I saw him on TV, speaking French with a Florida accent) that's what he's doing still: Vincent, over 60 now, still in love with dance, sharing that love with new crops of kids.

After the prodigal energy of Spadina Avenue, I had been left a year older and a bit duller in 1973, with no clear idea what I wanted my life to become -- what I wanted to do with it. For some years I still wouldn't know.

But, I think with none of them quite realizing it, Terry Thomas, Craig Sterling, and Vincent Warren helped me find my way.

Go on to 1974

Go back to: Contents page / My Home Page

This page: http://www.rbebout.com/bar/1973.htm

December 1999 / Last revised: June 22, 2003

Rick Bébout © 1999-2003 /

rick@rbebout.com